Cementation process

The cementation process is an obsolete technology for making steel by carburization of iron. Unlike modern steelmaking, it increased the amount of carbon in the iron. It was apparently developed before the 17th century. Derwentcote Steel Furnace, built in 1720, is the earliest surviving example of a cementation furnace. Another example in the UK is the cementation furnace in Doncaster Street, Sheffield.

Origins

The process was described in a treatise published in Prague in 1574. It was again invented by Johann Nussbaum of Magdeburg, who began operations at Nuremberg (with partners) in 1601. The process was patented in England by William Ellyot and Mathias Meysey in 1614.[1] At that date, the "invention" could consist merely of the introduction of a new industry or product, or even a mere monopoly. They evidently soon transferred the patent to Sir Basil Brooke, but he was forced to surrender it in 1619. A clause in the patent prohibiting the import of steel was found to be undesirable because he could not supply as much good steel as was needed.[2] Brooke's furnaces were probably in his manor of Madeley at Coalbrookdale (which certainly existed before the English Civil War) where two cementation furnaces have been excavated.[3] He probably used bar iron from the Forest of Dean, where he was a partner in farming the King's ironworks in two periods.

By 1631, it was recognised that Swedish iron was the best raw material and then or later particularly certain marks (brands) such as double bullet (so called from the mark OO) from Österby and hoop L from Leufsta (now Lövsta), whose mark consisted of an L in a circle, both belonging to Louis De Geer and his descendants. These were among the first ironworks in Sweden to use the Walloon process of fining iron, producing what was known in England as oregrounds iron. It was so called from the Swedish port of Öregrund, north of Stockholm, in whose hinterland most of the ironworks lay. The ore used came ultimately from the Dannemora mine.[2][4]

Process

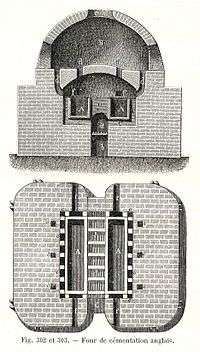

The process begins with wrought iron and charcoal. It uses one or more long stone pots inside a furnace. Typically, in Sheffield, each was 14 feet by 4 feet and 3.5 feet deep. Iron bars and charcoal are packed in alternating layers, with a top layer of charcoal and then refractory matter to make the pot or "coffin" airtight. Some manufacturers used a mixture of powdered charcoal, soot and mineral salts, called cement powder. In larger works, up to 16 tons of iron was treated in each cycle, though it can be done on a small scale, such as in a small furnace or blacksmith's forge.

Depending on the thickness of the iron bars, the pots were then heated from below for a week or more. Bars were regularly examined and when the correct condition was reached the heat was withdrawn and the pots were left until cool—usually around fourteen days. The iron had gained a little over 1% in mass from the carbon in the charcoal, and had become heterogeneous bars of blister steel.

The bars were then shortened, bound, heated and forge welded together to become shear steel. It would be cut and re welded multiple times, with each new weld producing a more homogeneous, higher quality steel. This would be done at most 3-4 times, as more is unnecessary and could potentially cause carbon loss from the steel.

Alternatively they could be broken up and melted in a crucible using a crucible furnace with a flux to become crucible steel or cast steel, a process devised by Benjamin Huntsman in Sheffield in the 1740s.

Similar processes

Notes

- K. C. Barraclough, Steel before Bessemer: I Blister Steel: the birth of an industry (The Metals Society, London, 1984), 48-52.

- P. W. King, 'The Cartel in Oregrounds Iron: trading in the raw material for steel during the eighteenth century' Journal of Industrial History 6(1) (2003), 25-49.

- P. Belford and R. A. Ross, 'English steelmaking in the seventeenth century: excavation of two cementation furnaces at Coalbrookdale' Historical Metallurgy 41(2) (2007), 105-123.

- Barraclough, K. C. (1990). Swedish iron and Sheffield steel. History of Technology. 12. pp. 1–39. ISBN 0-7201-2075-6.

References

- K. C. Barraclough, Steel before Bessemer I: Blister Steel: The Birth of an Industry (1985).

- K. C. Barraclough, "Swedish Iron and Sheffield Steel", History of Technology 12 (1990), 1–39.

- P. W. King, "The Cartel in Oregrounds Iron", Journal of Industrial History 6 (2003), 25–48.

- R. J. MacKenzie and J. A Whiteman, "Why pay more? An archaeometallurgical examination of 19th century Swedish Wrought iron and Sheffield blister steel", Historical Metallurgy 40(2) (2006), 138–49.