Cazumbá-Iracema Extractive Reserve

The Cazumbá-Iracema Extractive Reserve (Portuguese: Reserva Extrativista Cazumbá-Iracema) is an extractive reserve in the state of Acre, Brazil. The inhabitants extract rubber, Brazil nuts and other products from the forest for their own consumption or for sale, hunt, fish and engage in small-scale farming and animal husbandry. The reserve was created in 2002 as a sustainable use conservation area after a long campaign by the rubber tappers to prevent the government from evicting them and clearing the Amazon rainforest for cattle ranching. The reserve is rich in biodiversity, and helps form a buffer zone for the adjoining Chandless State Park. Due to decreases in rubber prices, some families want to clear the forest to raise cattle, which is seen as more profitable.[1]

| Cazumbá-Iracema Extractive Reserve | |

|---|---|

| Reserva Extrativista Cazumbá-Iracema | |

IUCN category VI (protected area with sustainable use of natural resources) | |

| |

| Nearest city | Sena Madureira, Acre |

| Coordinates | 9.360884°S 69.437189°W |

| Area | 750,795 hectares (1,855,250 acres) |

| Designation | Extractive reserve |

| Created | 19 September 2002 |

| Administrator | Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation |

Location

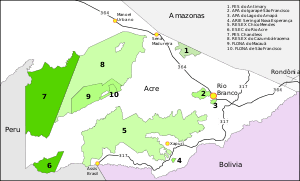

The Cazumbá-Iracema Extractive Reserve is the fifth largest in Brazil.[2] It is mainly in the municipality of Sena Madureira (97.71%) with a small part in the municipality of Manoel Urbano (2.29%), both in the state of Acre. It lies to the south of the BR-364 highway, and has an area of 750,795 hectares (1,855,250 acres). The reserve is bounded on the west by the Chandless State Park and on the southeast by the Macauã National Forest.[3] The western boundary is the watershed between the Caeté and Purus rivers. The eastern boundary is on the watershed of the Caeté and Macauã in the south, and then follows the Macauã northward.[4]

The terrain is dominated by gently sloping hills and steep ridges.[5] It is drained by tributaries of the Purus, which are typically meandering, and in the dry season may be difficult to navigate. The Caeté crosses the centre of the reserve.[3] The main tributaries of the Caeté are the Espera-aí, Canamary, Maloca and Santo Antônio streams. The main tributary of the Macauã in the east is the Riozinho stream.[2] There are flat areas and alluvial terraces along the rivers and large streams, subject to periodic or permanent flooding and holding oxbow lakes where meanders have been cut off from the rivers.[5]

The reserve has a wet tropical climate. Average temperatures are 23.5 to 25.5 °C (74.3 to 77.9 °F), slightly cooler in July and slightly warmer in October. Average annual rainfall is 2,000 to 2,500 millimetres (79 to 98 in), with a short dry season from June to September. Relative humidity is 80–90% throughout the year. The soils are generally low in nutrients and poorly drained.[3]

Vegetation is mainly open palm rainforest, with smaller areas of open bamboo rainforest and uniform canopy rainforest along the Caeté River. Based on cursory studies of flora the forest includes various plant species with economic value or potential including Euterpe precatoria, Phytelephas macrocarpa, Hevea brasiliensis, Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa), Copaifera species, Cedrela odorata, Dipteryx odorata, Torresea acreana and Swietenia macrophylla.[3] Preliminary studies of fauna have recorded 179 birds, 44 mammals, 18 fish and 8 reptiles. Species listed by the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources as threatened are the giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), giant armadillo (Priodontes maximus), jaguar (Panthera onca) and bush dog (Speothos venaticus).[3]

Historical background

_(14782968552).jpg)

Rubber extraction began in Acre in the 1870–90 period, using workers from the dry northeast of Brazil.[6] The rubber was extracted from trees growing naturally in the forest. In the 1870s seeds were smuggled out of Brazil to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, in London, and from there the plants were distributed to Malaya and elsewhere in South East Asia. British companies developed huge rubber tree plantations in Malaya to meet growing demand for tyres after 1900.[7] By 1912 Malaya exceeded Brazilian output and charged lower prices. Many Brazilian producers failed and rubber concessions were abandoned. The rubber tappers began to cultivate clearings and to hunt and extract other forest products.[6]

During World War II (1939–45) Japan occupied Malaya and cut off its rubber supplies. The United States funded an ambitious program to reactivate Brazilian rubber extraction.[6] Many of the residents of the Cazumbá-Iracema Extractive Reserve are descended from "rubber soldiers" who were brought to Acre in this period to extract rubber for military use.[8] The government advertised "a new life in the Amazon", but the workers who came there from the northeast of Brazil found that conditions were harsh. With no easy way to leave, they were forced to adapt to the forest and learn how to use its resources.[9] After the war ended Malaya again became the preferred international supplier of rubber, but the government kept the rubber industry running through subsidies.[6]

The Brazilian military government that ruled from 1964 to 1985 wanted to open up the Amazon to protect national sovereignty, and resettled thousands of people from the south. The Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária (National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform, INCRA) created farm settlements in Acre in the 1970s and 1980s along new roads through the forest. The settlers would clear the land so they could raise cattle and grow a few crops.[8] In the 1980s INCRA expropriated part of the area of the present Cazumbá-Iracema Extractive Reserve to implement the Boa Esperança (Good Hope) farm settlement project.[6] The land included the Iracema seringal (rubber extraction area) on the Caeté River.[3] The rubber tappers began a long campaign to preserve the forest, sometimes stopping loggers with human chains of women and children.[8]

In the early 1990s rubber prices fell and many families left.[8] INCRA threatened to evict more than 200 remaining families from the Iracema seringal so it could be converted to cattle ranching under the government's agricultural extension program. Most of the families were living in tiny isolated settlements along over 37 miles (60 km) of the upper Caeté River.[10] Aldeci Cerqueira Maia (known as Nenzinho) was one of the local leaders.[11] He organised the Cazumbá Rubber Tappers Association (ASSC) in 1993 to fight the INCRA evictions and with the help of Father Paolino Baldassari, the Catholic priest, managed to have them revoked.[10] In 1995 Nenzinho persuaded a number of families to move to Nucleo Cazumbá, a central location on land his grandfather had owned, and form a cooperative to share the resources.[12] The cooperative prevented subdivision of the area and land speculation.[3] It transported and sold the rubber. When prices dropped further the members began to also harvest Brazil nuts for sale and to grow crops for food.[8] A school was established in 1993 and a dirt road reached the reserve in 1997, although the rains often make it unusable.[8]

Creation and operation of the reserve

From around 2000 there has been growing awareness that sealing off protected areas and evicting the local people is less effective than engaging the local people in sustainable economic activities and conservation efforts.[13] The ASSC contacted the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) in 1999 after years of negotiations with INCRA had stalled. IBAMA undertook studies and identified that the reserve was needed. The proposal was supported by government and civil society institutions in Sena Madureira.[2] The Catholic Church gave strong backing for creation of the reserve.[3] A letter from Nenzinho to the president of Brazil on 14 December 2001 called the Brazilian Amazon the lungs of the Earth and said, “We are the real conservationists who ... still live in the same places, preserving the forest around us."[11]

The Cazumbá-Iracema Extractive reserve was created by presidential decree on 19 September 2002. On 3 November 2003 INCRA recognised the reserve as an agricultural project for 243 families.[3] Relations between IBAMA and the people of the reserve were tense at first. IBAMA dealt only with the ASSC president, was focused on conservation and wanted to stop traditional ways of exploiting the natural resources. Things improved when president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva appointed Marina Silva, daughter of a rubber tapper, as minister of the environment. She introduced policies that support social involvement in sustainability. They improved further when the independent Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio) was formed in 2007 to manage the federal protected areas.[14]

The conservation unit is supported by the Amazon Region Protected Areas Program.[15] The deliberative council was established on 9 March 2006.[3] The participatory management plan was published in December 2007.[16] It was approved on 28 August 2008.[3] The council follows a participatory approach that the ICMBio manager of the reserve says is effective in meeting community needs.[2] ICMBio and the Ministry of Agrarian Development have held citizenship events at which residents get documents such as Cadastro de Pessoas Físicas taxpayer numbers and identity cards, and hear lectures about the federal government and their rights such as the Bolsa Família, maternity pay, sick pay and pensions.[17] An audit of 247 conservation units in Brazil published in November 2013 found that only ten had a high level of implementation, one of which was Cazumbá-Iracema.[2] In October 2015 Cazumbá-Iracema won the third prize out of 120 entrants for the Pronatec Entrepreneur Award for an agribusiness project for processing açaí palm pulp. The enterprise was employing fifty people in collection, transport and production. The award is promoted by Serviço Brasileiro de Apoio às Micro e Pequenas Empresas in partnership with the Ministry of Education.[18]

As of 2016 there were three biodiversity sampling stations in the reserve that had been collecting data for two years. Six members of the community worked as monitors and 25 were trained to work in the project.[19] In April 2016 fifteen residents of three of the reserve's regions – Cazumbá, Médio Caeté and Alto Caeté – participated in the second training course for basic protocols for monitoring biodiversity in situ, run by the Instituto de Pesquisas Ecológicas (Institute for Ecological Research). The reserve still has large untouched areas and some of the greatest biodiversity of large mammals in the world. The course gave the participants guidelines on monitoring mammals and also frugivorous butterflies and woody plants.[19] Monitoring is of value in understanding the local biodiversity, and recognising possible effects of climate change or human pressure. Community involvement is an important aspect.[19]

People and pressures

As of 2009 there were 1,300 people in 270 families. 50% were illiterate and about 20% of the children did not attend school.[3] In 2010 the community had 96 primary school students and 15 secondary students.[8] The main community is Nucleo Cazumbá, with about 40 families in 2014 out of 350 families in the reserve. Nucleo Cazumbá is closest to the road to the city of Sena Madureira, and is where most services are provided.[10] New families are not allowed to move to the reserve, whose population is already increasing naturally.[2] 96% of the vegetation was still natural forest in 2009.[20]

A review of 34 farmers in the reserve in 2007–08 found they used forest clearings, gardens, pastures and ponds, and also gathered forest products, hunted and fished. They did not use modern agricultural machinery or supplies. Income came from sale of flour, bananas, animals, wood, nuts and rubber and from public subsidies.[21] The clearings range in size from 1 to 3 hectares (2.5 to 7.4 acres), and are used continuously for up to three years to grow annual crops, legumes, and perennial fruits. They are then abandoned for natural regeneration, or in some cases converted to pasture.[20] Farmers work alone or in communal teams. They exploit about 170 agricultural species and cultivars including domesticated forest species, fruits, medicinal plants and vegetables, used for personal consumption or for barter with relatives and neighbours.[22] Cassava is the only year-round staple. Hunted animals include paca, pig and pampas deer. [3]

Extraction of rubber and nuts provide the main sources of income.[3] Producers in 2010 were receiving a subsidised price for rubber, but that was still much lower than in 1980.[8] Other resources extracted for sale included wood, copaiba oil, honey and the fruits of açaí palm and patauá (Oenocarpus bataua).[3] Some families were trying to diversify, for example using the latex fabric encauchado to make wall hangings or mouse pads shaped like Amazon forest leaves.[8] The reserve helps maintain people in the country rather than drifting to the slums around the city, provides ecosystem services and acts as a buffer around the Chandless State Park.[3]

However, there are continued pressures.[8] The majority of families in Nucleo Cazumbá own a TV and are aware of the outside world. There is no mobile phone coverage but young people still want a phone, if only for games.[1] The 2007–08 report found that there was growth in extraction of wood for illegal sale to third parties.[23] In 2008 several thousand head of cattle were discovered in a large illegally deforested area of the reserve.[8] Moacyr Araujo Silva of WWF Brasil points out that extraction is less profitable and takes more work than cattle breeding. He argues that raising cattle will allow people to earn the money they need to buy commodities or to send their children to be educated in the cities.[1] In the nearby Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve each family is allowed to clear 15 hectares (37 acres) for pasturage. Almost all raise cattle and some exceed the limit on forest clearance. A community leader said in 2013 that the son of a tapper born today wants to raise cattle.[24]

Notes

- Daniel Guijarro 2014, p. 20.

- Rayssa Natani 2014.

- RESEX do Cazumbá-Iracema – ISA.

- Arlindo Gomes Filho 2007, p. 15–16.

- Arlindo Gomes Filho 2007, p. 18.

- Arlindo Gomes Filho 2007, p. 14.

- Taylor 2006, p. xxi.

- Mario Osava 2010.

- Daniel Guijarro 2014, p. 9.

- Daniel Guijarro 2014, p. 13.

- Daniel Guijarro 2014, p. 10.

- Daniel Guijarro 2014, p. 13–14.

- Daniel Guijarro 2014, p. 5.

- Daniel Guijarro 2014, p. 17.

- Full list: PAs supported by ARPA.

- Arlindo Gomes Filho 2007, p. vii.

- Resex do Cazumbá-Iracema (AC) realiza Projeto Cidadão.

- Reserva acreana Cazumbá-Iracema ganha prêmio.

- Comunidade da RESEX do Cazumbá-Iracema participa ... IPE.

- Siviero, Haverroth & Evangelista 2009, p. 1099.

- Siviero, Haverroth & Evangelista 2009, p. 1098.

- Siviero, Haverroth & Evangelista 2009, p. 1100.

- Siviero, Haverroth & Evangelista 2009, p. 1101.

- Yuri Marcel 2013.

Sources

- Arlindo Gomes Filho (December 2007), Plano de Manejo da Reserva Extrativista do Cazumbá-Iracema (PDF) (in Portuguese), Sena Madureira – AC: Ministério do Meio Ambiente – MMA; Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade – ICMBio, retrieved 2016-06-17

- Comunidade da RESEX do Cazumbá-Iracema participa do segundo curso de capacitação do Programa de Monitoramento Participativo da Biodiversidade (in Portuguese), IPE: Instituto de Pesquisas Ecológicas, April 2016, archived from the original on 2016-10-12, retrieved 2016-06-17

- Daniel Guijarro (2014), A New Life in the Amazon: Conservation, Livelihood and Well-being in Brazil's Cazumbá-Iracema Extractive Reserve: A Critical Story of Change (PDF), WWF-US, retrieved 2016-06-17

- Full list: PAs supported by ARPA, ARPA, retrieved 2016-08-07

- Mario Osava (5 November 2010), BRAZIL: Battle Between Jungle and Livestock in the Amazon, IPS, retrieved 2016-06-17

- Rayssa Natani (15 February 2014), "Reserva Cazumbá está entre as 10 no país com alto grau de implementação", G1 Globo (in Portuguese), retrieved 2016-06-17

- Reserva acreana Cazumbá-Iracema ganha prêmio Pronatec Empreendedor (in Portuguese), Acreaovivo.com, 25 October 2015, retrieved 2016-06-17

- Resex do Cazumbá-Iracema (AC) realiza Projeto Cidadão (in Portuguese), MMA – ARPA, retrieved 2016-06-17

- RESEX do Cazumbá-Iracema (in Portuguese), ISA: Instituto Socioambiental, retrieved 2016-06-16

- Siviero, Amauri; Haverroth, Moacir; Evangelista, Ricardo (November 2009), "Agricultura na Reserva Extrativista Cazumbá-Iracema, Acre" (PDF), Rev. Bras. De Agroecologia, 4 (2), retrieved 2016-06-17

- Taylor, T.K. (2006-02-24), Sunset of the Empire in Malaya: A New Zealander's Life in the Colonial Education Service, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 978-0-85771-715-3, retrieved 2016-06-18

- Yuri Marcel (22 December 2013), "'Filho de seringueiro hoje já nasce querendo criar gado', diz extrativista", G1 Globo (in Portuguese), retrieved 2016-06-19