Caryl Brahms

Doris Caroline Abrahams (8 December 1901 – 5 December 1982), commonly known by the pseudonym Caryl Brahms, was an English critic, novelist, and journalist specialising in the theatre and ballet. She also wrote film, radio and television scripts.

As a student at the Royal Academy of Music in London, Brahms was dissatisfied with her own skill as a pianist, leaving without graduating. She contributed light verse, and later stories for satirical cartoons, to the London paper The Evening Standard in the late 1920s. She recruited a friend, S. J. Simon, to help her with the cartoon stories, and in the 1930s and 40s they collaborated on a series of comic novels, some with a balletic background and others set in various periods of English history. At the same time as her collaboration with Simon, Brahms was a ballet critic, writing for papers including The Daily Telegraph. Later, her interest in ballet waned, and she concentrated on reviewing plays.

After Simon's sudden death in 1948, Brahms wrote solo for some years, but in the 1950s she established a second long-running collaboration with the writer and broadcaster Ned Sherrin, which lasted for the rest of her life. Together they wrote plays and musicals for the stage and television, and published both fiction and non-fiction books.

Life and career

Early years

Brahms was born in Croydon, Surrey. Her parents were Henry Clarence Abrahams, a jeweller, and his wife, Pearl née Levi, a member of a Sephardic Jewish family who had come to Britain from the Ottoman Empire a generation earlier.[1] She was educated at Minerva College, Leicestershire and at the Royal Academy of Music, where she left before graduating. Her biographer Ned Sherrin wrote, "already an embryo critic, she did not care to listen to the noise she made when playing the piano."[1]

While at the Academy, Brahms wrote light verse for the student magazine. The London evening newspaper The Evening Standard began to print some of her verses. Brahms adopted her pen-name so that her parents should not learn of her activities: they envisaged "a more domestic future" for her than journalism.[1] The name "Caryl" was also usefully ambiguous as regards gender.[2] In 1926, the artist David Low began to draw a series of satirical cartoons for The Evening Standard, featuring a small dog named "Mussolini" (later shortened to "Musso", after protests from the Italian embassy).[3] Brahms was engaged to write the stories for the cartoons.[3]

In 1930, Brahms published a volume of poems for children, The Moon on My Left, illustrated by Anna Zinkeisen. The Times Literary Supplement judged the verses to be in the tradition of A. A. Milne, "but the disciple's gift is too frequently spoiled by her lack of control. She uses too many capital letters, and too many exclamation marks, too many round O's in long chains, and she is too facetious".[4] The reviewer quoted with approval an extract from one of her poems, a child's thoughts by candlelight:

- I like things round,

- I like the moon,

- And the smooth inside

- Of a silver spoon;

- I like pennies –

- And Sixpence too –

- I LIKE things round –

- Don't you?

This was followed the next year by a second volume, Sung Before Six, published under a different pen-name, Oliver Linden.[5] She reverted to her more familiar pseudonym for a third volume, Curiouser and Curiouser, published in 1932.[5]

Brahms and Simon

Towards the end of the 1920s, finding it difficult to keep up the supply of new stories for Low's cartoon series, Brahms enlisted the help of a Russian friend, S. J. Simon, whom she had met at a hostel when they were both students.[2] The partnership was successful, and Brahms and Simon started to write comic thrillers together. The first, A Bullet in the Ballet, had its genesis in a frivolous fantasy spun by the collaborators when Brahms was deputising for Arnold Haskell as dance critic of The Daily Telegraph. Brahms proposed a murder mystery set in the ballet world with Haskell as the corpse. Simon took the suggestion as a joke, but Brahms insisted that they press ahead with the plot (although Haskell was not a victim in the finished work).[3] The book introduced the phlegmatic Inspector Adam Quill and the excitable members of Vladimir Stroganoff's ballet company, who later reappeared in three more books between 1938 and 1945.[5] Some thought that Stroganoff was based on the impresario Sergei Diaghilev, but Brahms pointed out that Diaghilev appears briefly in the novels in his own right, and she said of Stroganoff, "Suddenly he was there. I used to have the impression that he wrote us, rather than that we wrote him."[3]

Before the novel was complete, Brahms published her first prose book, Footnotes to the Ballet (1936), a symposium edited (or as the title page read "assembled") by Brahms, with contributors including Haskell, Constant Lambert, Alexandre Benois, Anthony Asquith and Lydia Sokolova. The book was well received; the anonymous Times Literary Supplement (TLS) reviewer singled out Brahms's own contributions for particular praise.[6] The reception of A Bullet in the Ballet the following year was even warmer. In the TLS, David Murray wrote that the book provoked "continuous laughter. … Old Stroganoff with his troubles, artistic, amorous and financial, his shiftiness, and his perpetual anxiety about the visit of the great veteran of ballet-designers – 'if 'e come', is a vital creation. ... The book stands out for shockingness and merriment."[7] The sexual entanglements, both straight and gay, of the members of the Ballet Stroganoff are depicted with a cheerful matter-of-factness unusual in the 1930s. Murray commented, "True, a certain number of the laughs are invited for a moral subject that people used not to mention with such spade-like explicitness, if at all."[7] In The Observer, "Torquemada" (Edward Powys Mathers) commented on the "sexual reminiscences of infinite variety" and called the novel "a delicious little satire" but "not a book for the old girl".[8] In the 1980s, Michael Billington praised the writing: "a power of language of which Wodehouse would not have been ashamed. As a description of a domineering Russian mother put down by her ballerina daughter, you could hardly better: 'She backed away like a defeated steamroller.'"[9]

The book was a best-seller in the UK, and was published in an American edition by Doubleday.[5][10] The authors followed up their success with a sequel, Casino for Sale (1938), featuring all the survivors from the first novel and bringing to the fore Stroganoff's rival impresario, the rich and vulgar Lord Buttonhooke.[11] It was published in the US as Murder à la Stroganoff.[5] The Elephant is White (1939), tells the story of a young Englishman and the complications arising from his visit to a Russian night club in Paris. It was not well reviewed.[12] A third Stroganoff novel, Envoy on Excursion (1940) was a comic spy-thriller, with Quill now working for British intelligence.[13]

In 1940, Brahms and Simon published the first of what they called "backstairs history", producing their own highly unreliable comic retellings of English history. Don't, Mr. Disraeli! is a Victorian Romeo and Juliet story, with affairs of the feuding middle-class Clutterwick and Shuttleforth families interspersed with 19th-century vignettes (Gilbert and Sullivan at the Savage Club, for example) and anachronistic intruders from the 20th century, including Harpo Marx, John Gielgud and Albert Einstein.[14] In The Observer, Frank Swinnerton wrote, "They turn the Victorian age into phantasmagoria, dodging with the greatest possible nimbleness from the private to the public, skipping among historic scenes, which they often deride, and personal jokes and puns, and telling a ridiculous story while they communicate a preposterous – yet strangely suggestive – impression of nineteenth-century life."[15]

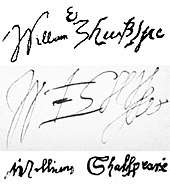

To follow their Victorian book, Brahms and Simon went back to Elizabethan times, with No Bed for Bacon (1941). Unlike the earlier work, the narrative and allusions are confined to the age in which the book is set. The plot concerns a young woman who disguises herself as a boy to gain membership of Richard Burbage's and William Shakespeare's, theatrical company (a device later employed by Tom Stoppard as the central plot of his 1999 screenplay Shakespeare in Love).[16] Reviewing the book in the Shakespeare Quarterly, Ernest Brennecke wrote:

There is plenty of fun in the lighthearted fantasy recently perpetrated by Caryl Brahms and S. J. Simon. Their book is irresponsible, irreverent, impudent, anachronistic, undocumented. The authors warn all scholars that it is also "fundamentally unsound." Poppycock! It is one of the soundest of recent jobs. The more the reader knows about Shakespeare and his England, the more chuckles and laughs he will get out of the book. It is erudite, informed, and imaginative. It solves finally the question of the "second-best" bed, Raleigh's curious obsession with cloaks, Henslowe's passion for burning down Burbage's theatres, and Shakespeare's meticulous care for his spelling.[17]

in 1944, Brahms published her first solo prose work, a study of the dancer and choreographer Robert Helpmann. The reviewer in The Musical Times commended it as "a good deal more than a tribute to Robert Helpmann ... its enthusiasm is of the informed variety that inspires respect, the more so as it is balanced and sane." Among Brahms's many digressions from the main subject of the book was a section, praised in The Musical Times, explaining why the appropriation of symphonic music for ballet is as unsatisfactory to the ballet purist as to the music lover. Brahms included snippets of overheard remarks, confirming, as the reviewer noted, that "ballet audiences are the least musical of all; are they also among the least intelligent?"[18] Brahms's own enthusiasm for ballet remained intact for the time being, but it was later to dwindle.[3]

With Simon, Brahms completed four more novels and a collection of short stories. No Nightingales (1944) is set in a house in Berkeley Square, haunted by two benevolent ghosts coping with new occupants between the reigns of Queen Anne and George V. It was filmed after the war as The Ghosts of Berkeley Square (released on 30 October 1947), starring Robert Morley and Felix Aylmer. Titania has a Mother (1944) is a satirical jumble of pantomime, fairy tales, and nursery rhymes. Six Curtains for Stroganova (1945) was the collaborators' last ballet novel. Trottie True (1946) is a back-stage comedy set in the era of Edwardian musical comedy, which was later filmed. To Hell with Hedda (1947) is a collection of short stories.

In 1948, the collaborators had begun work on another book, You Were There, when Simon suddenly died, aged 44. Brahms completed the work, which she described as "less a novel than an out-of-date newsreel", covering the period from the death of Queen Victoria to 1928. Reviewing the book, Lionel Hale wrote, "The vivacity of this raffish chronicle is unflagging."[19]

Collaborations with S J Simon 1937 A Bullet in the Ballet. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 752997851. 1938 Casino for Sale. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 558706784. Published in America as Murder à la Stroganoff. New York: Doubleday, Doran. 1938. OCLC 11309700. 1939 The Elephant is White. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 558706826. 1940 Envoy on Excursion. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 154388199. 1940 Don't, Mr. Disraeli!. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 462681016. 1941 No Bed for Bacon. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 558706853. 1944 No Nightingales. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 558706895. 1945 Six Curtains for Stroganova. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 9495601. Published in America as Six Curtains for Natasha. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott. 1946. OCLC 1040925. 1946 Trottie True. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 475946887. 1947 To Hell with Hedda! and other stories. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 8298701. 1950 You Were There – Eat, drink, and be merry, for yesterday you died. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 154216656.

Brahms and Sherrin

After Simon's death, Brahms was sure that she never wished to collaborate with any other writer.[3] Her solo works from this period were A Seat at the Ballet (1951) a guide for newcomers,[20] and a melodramatic romantic novel, Away Went Polly (1952), of which the critic Julian Symons wrote, "Miss Brahms is perhaps aiming at elegant sophistication; she achieves more often the ecstatically thrilled note of a saleswoman in a high-class dress shop."[21] She expanded her range as a critic to include opera and drama as well as ballet.[1]

In 1954, Brahms received a letter from the young Ned Sherrin asking her permission to adapt No Bed for Bacon as a stage musical.[1] Her first reaction was to ring him to prevent him from going any further, but his voice "sounded so young and so nice" that Brahms gave in.[3] She agreed to collaborate with Sherrin on the adaptation. It was well-reviewed,[22] but was not a box-office success.[1] Nonetheless, in Sherrin's words, "it laid the foundation of a partnership which over the next twenty-eight years produced seven books, many radio and television scripts, and several plays and musicals for the theatre."[1] In 1962 they published a novel, Cindy-Ella – or, I Gotta Shoe, described in the TLS as "a charming, sophisticated fairy-tale … retelling the Cinderella story rather as a coloured New Orleans mother might tell it to her (precocious) daughter".[23] It was based on a radio play that Brahms and Sherrin had written in 1957.[5] At the end of 1962 they adapted it again, as a stage musical, starring Cleo Laine, Elisabeth Welch and Cy Grant.[24]

In 1963, Brahms published her second solo novel, No Castanets, a gently humorous work about the Braganza empire in Brazil.[25] When Sherrin became a television producer in the 1960s, he and Brahms always wrote the weekly topical opening number for the ground-breaking satirical show That Was The Week That Was and its successors.[9] Their collaboration won them the Ivor Novello award for the best screen song.[3]

By the 1960s, Brahms's enthusiasm for ballet was waning.[1] She later commented, "Really I've left the ballet behind me because I became very bored with watching the girl in the third row moving forward to be in the second row; and when you have lost that feeling, you are no longer the person to write about ballet."[3] Her professional focus, both as a critic and as an author, was increasingly the theatre. Privately, her enthusiasm for ballet transferred itself to show-jumping, of which she became a devotee.[1]

With Sherrin, Brahms wrote and adapted prolifically for the theatre and television. Their collaborations included Benbow Was His Name, televised in 1964, staged in 1969; The Spoils (adapted from Henry James's The Spoils of Poynton), 1968; Sing a Rude Song, a musical biography of Marie Lloyd, 1969; adaptations of farces by Georges Feydeau, Fish Out of Water, 1971, and Paying the Piper (1972); a Charles Dickens play, Nickleby and Me, 1975; Beecham, 1980, a celebration of the great conductor; and The Mitford Girls, 1981.[5] For BBC television, they adapted a long sequence of Feydeau farces between 1968 and 1973 under the series title Ooh! La-la![5] She was a member of the board of the National Theatre from 1974 until her death.[1]

As a critic and columnist, Brahms wrote for many publications, principally The Evening Standard.[5] She included an account of her theatrical experiences in a book of memoirs, The Rest of the Evening's My Own (1964), and left a second volume of reminiscences unfinished at her death, which Sherrin edited and augmented as Too Dirty for the Windmill (1986). For television the collaborators devised a series of programmes about songs from musicals, on which they later based a book, Song by Song – Fourteen Great Lyric Writers (1984) published after Brahms's death.[5]

Last years

In 1975, Brahms published a study of Gilbert and Sullivan and their works. The book was lavishly illustrated, but her text, marred by numerous factual errors,[26] merely confused the subject. In The Guardian, Stephen Dixon wrote that Brahms "manages to coast over the fact that we've heard it all before by going off at entertaining tangents in a series of anecdotes, personal interpolations, witty irrelevancies and theories."[27] The following year, she published Reflections in a Lake: A Study of Chekhov's Greatest Plays.[5] Among her last works of fiction were new short stories about Stroganoff, included in her collection Stroganoff in Company (1980), which also included some stories developed from ideas jotted down by Anton Chekhov in his notebooks. The reviewer of the TLS welcomed the reappearance of Stroganoff and judged the Chekhov stories "impressive in their evocation of another era and in their tribute to a more serious and formal art."[28]

Brahms never married. Frederic Raphael notes that "her one true love", Jack Bergel, was killed in the Second World War.[2] She died at her flat in Regent's Park, London aged 80.[1]

Notes

- Sherrin, Ned. "Abrahams, Doris Caroline [Caryl Brahms] (1901–1982)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 24 September 2011 (subscription required)

- Raphael, Frederick, "Writing in pairs", The Times Literary Supplement, 6 June 1986, p. 609

- Watts, Janet. "Another helping of Stroganoff", The Guardian, 16 August 1975, p. 8

- "Rhyme Stories", The Times Literary Supplement, 20 November 1930, p. 965

- "Doris Caroline Abrahams", Contemporary Authors Online, Gale, 2003, accessed 24 September 2011 (subscription required)

- "Thirty Years of Ballet", The Times Literary Supplement, 23 May 1936, p. 431

- "A Bullet in the Ballet", Times Literary Supplement, 26 June 1937, p. 480

- Torquemada. "Handmaids to Murder", The Observer, 11 July 1937, p. 7

- Billington, Michael. "Caryl Brahms", The Guardian, 6 December 1982, p. 11

- "A Bullet in the Ballet", Worldcat, accessed 24 September 2011

- "New Novels", The Times, 20 May 1938, p. 10

- Swinnerton, Frank. "Limits to credulity", The Observer, 27 August 1939, p. 6

- "New Novels", The Times, 18 May 1940, p. 14

- Brahms and Simon (1940), pp. 47, 53, 56 and 104

- Swinnerton, Frank. "Experiments with time", The Observer, 10 November 1940, p. 5

- Salvador Bello, Mercedes. "Marc Norman and Tom Stoppard 1999: Shakespeare in Love (the screenplay)", Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Atlantis XXI (1999), accessed 24 September 2011

- Brennecke, Ernest. "All Kinds of Shakespeares – Factual, Fantastical, Fictional", Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 4 (October, 1950), pp. 272–280 (subscription required)

- "Robert Helpmann, Choreographer by Caryl Brahms", The Musical Times, Vol. 85, No. 1211 (1 January 1944), p. 16 (subscription required)

- Hale, Lionel. "New Novels", The Observer, 11 June 1950, p. 7

- "Ballet-goers' Guide", The Times Literary Supplement, 9 November 1951, p. 706

- "Drama and Melodrama", The Times Literary Supplement, 12 December 1952, p. 813

- "Engaging Musical Romp", The Times, 10 June 1959, p. 7

- "Humour and Fantasy", The Times Literary Supplement, 14 December 1962, p. 978

- "An Epic Theatre Cinderella", The Times, 18 December 1962, p. 5

- "W. H. Allen", The Times, 11 April 1963, p. 15

- For example, rendering Selina Dolaro as "Doloro", Helen Lenoir as "Lenoire" and Sir George Macfarren as "Macfarlane", wrongly describing the peers in Iolanthe as "scarlet-trained" and repeating a myth that The Mikado was inspired when a Japanese sword fell from the wall of Gilbert's study: see Brahms (1975), pp. 64, 100, 125, 122 and 137, and Jones, Brian (Spring 1985). "The sword that never fell". W. S. Gilbert Society Journal. 1 (1): 22–25.

- Dixon, Stephen. "Regular rummy old world", The Guardian, 29 January 1976, p. 9

- "High and low", The Times Literary Supplement, 19 September 1980, p. 1047

External links