Carnitine palmitoyltransferase II deficiency

Carnitine palmitoyltransferase II deficiency is an autosomal recessively inherited genetic metabolic disorder characterized by an enzymatic defect that prevents long-chain fatty acids from being transported into the mitochondria for utilization as an energy source. The disorder presents in one of three clinical forms: lethal neonatal, severe infantile hepatocardiomuscular and myopathic.

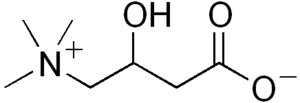

| Carnitine palmitoyltransferase II deficiency | |

|---|---|

| Other names | CPT-II, CPT2 |

| |

| Carnitine | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

First characterized in 1973 by DiMauro and DiMauro the adult myopathic form of this disease is triggered by physically strenuous activities and/or extended periods without food and leads to immense muscle fatigue and pain.[1] It is the most common inherited disorder of lipid metabolism affecting the skeletal muscle of adults, primarily affecting males. CPT II deficiency is also the most frequent cause of hereditary myoglobinuria.

Signs and symptoms

The three main types of carnitine palmitoyltransferase II deficiency classified on the basis of tissue-specific symptomatology and age of onset. Among the few people diagnosed with CPT2, some have unknown and/or novel mutations that place them outside these three categories while remaining positive for CPT2.

Neonatal form

The neonatal form is the least common clinical presentation of this disorder and is almost invariably fatal in rapid fashion regardless of intervention. Symptomatic onset has been documented just hours after birth to within 4 days of life. Affected newborns typically experience respiratory failure, low blood sugar, seizures, liver enlargement, liver failure, and heart enlargement with abnormal heart rhythms leading to cardiac arrest. In most cases, elements of abnormal brain and kidney development are apparent, sometimes even at prenatal ultrasound. Infants with the lethal neonatal form usually live no longer than a few months.[2] Neuronal migration defects have also been documented, to which the CNS pathology of the disorder is often attributed.

Infantile form

Symptomatic presentation usually occurs between 6 and 24 months of age, but the majority of cases have been documented in children less than 1 year of age. The infantile form involves multiple organ systems and is primarily characterized by hypoketotic hypoglycemia (recurring attacks of abnormally low levels of fat breakdown products and blood sugar) that often results in loss of consciousness and seizure activity. Acute liver failure, liver enlargement, and cardiomyopathy are also associated with the infantile presentation of this disorder. Episodes are triggered by febrile illness, infection, or fasting. Some cases of sudden infant death syndrome are attributed to infantile CPT II deficiency at autopsy.

Adult form

This exclusively myopathic form is the most prevalent and least severe phenotypic presentation of this disorder. Characteristic signs and symptoms include rhabdomyolysis (breakdown of muscle fibers and subsequent release of myoglobin), myoglobinuria, recurrent muscle pain, and weakness. The myoglobin release causes the urine to be red or brown and is indicatory of damage being done to the kidneys which ultimately could result in kidney failure.[3] Muscle weakness and pain typically resolves within hours to days, and patients appear clinically normal in the intervening periods between attacks. Symptoms are most often exercise-induced, but fasting, a high-fat diet, exposure to cold temperature, sleep deprivation, or infection (especially febrile illness) can also provoke this metabolic myopathy. In a minority of cases, disease severity can be exacerbated by three life-threatening complications resulting from persistent rhabdomyolysis: acute kidney failure, respiratory insufficiency, and episodic abnormal heart rhythms. Severe forms may have continual pain from general life activity. The adult form has a variable age of onset. The first appearance of symptoms usually occurs between 6 and 20 years of age but has been documented in patients as young as 8 months as well as in adults over the age of 50. Roughly 80% cases reported to date have been male.

Biochemistry

Enzyme structure

The CPT system directly acts on the transfer of fatty acids between the cytosol and the inner mitochondrial matrix.[4] CPT II shares structural elements with other members of the carnitine acyltransferase protein family.[5] The crystal structure of rat CPT II was recently elucidated by Hsiao et al.[6] The human homolog of the CPT II enzyme shows 82.2% amino acid sequence homology with the rat protein.[7] Significant structural and functional information about CPT II has thus been derived from the crystallographic studies with the rat protein.

In addition to similarities shared by the acyltransferases, CPT II also contains a distinct insertion of 30 residues in the amino domain that forms a relatively hydrophobic protrusion composed of two alpha helices and a small anti-parallel beta sheet.[6] It has been proposed that this segment mediates the association of CPT II with the inner mitochondrial membrane.[6] Moreover, the insert might also facilitate the shuttling of palmitoylcarnitines directly into the active site of CPT II after translocation across the inner membrane by virtue of its juxtaposition to the active site tunnel of the enzyme.[6]

Catalytic mechanism

CPT II catalyzes the formation of palmitoyl-CoA from palmitoylcarnitine imported into the matrix via the acylcarnitine translocase. The catalytic core of the CPT II enzyme contains three important binding sites that recognize structural aspects of CoA, palmitoyl, and carnitine.[8]

Although kinetic studies are hindered by high substrate inhibition, strong product inhibition, very low Km values for the acyl-CoA substrates, and complex detergent effects with respect to micelle formation,[8] studies have shown that CPT II demonstrates a compulsory-order mechanism in which the enzyme must bind CoA before palmitoylcarnitine, and then the resulting product palmitoyl-CoA is the last substrate to be released from the enzyme. The carnitine binding site is made accessible by the conformational change induced in the enzyme by the binding of CoA.[8] This ordered mechanism is believed to be important so that the enzyme responds appropriately to the acylation state of the mitochondrial pool of CoA despite the fact that the concentrations of both CoA and acyl-CoA found in the matrix well exceed the measured km value of the enzyme (most CPT II will already have bound the CoA).[9]

The histidine residue (at position 372 in CPT II) is fully conserved in all members of the carnitine acyltransferase family and has been localized to the enzyme active site, likely playing a direct role in the catalytic mechanism of the enzyme.[5] A general mechanism for this reaction is believed to involve this histidine acting as a general base. More specifically, this reaction proceeds as a general base-catalyzed nucleophilic attack of the thioester of acetyl-CoA by the hydroxyl group of carnitine.[10]

Biochemical significance of disease-causing mutations

The majority of the genetic abnormalities in CPT II deficient patients affect amino acid residues somewhat removed from the active site of the enzyme. Thus, these mutations are thought to compromise the stability of the protein rather than the catalytic activity of the enzyme.[6] Theories regarding the biochemical significance of the two most common mutations are noted below:

- Ser113Leu Hsiao et al.[6] theorize that this mutation may disturb the hydrogen-bonding between Ser113 and Arg 498 and the ion-pair network between Arg498 and Asp376, thereby indirectly affecting the catalytic efficiency of the His372 residue. Isackson et al.[5] suggest that this mutation increases the thermolability of the enzyme, structurally destabilizing it. This is noteworthy in light of the fact that this mutation is associated with the exercise-induced adult form (i.e., rising core body temperature may exacerbate enzymatic defects leading to symptomatic presentation).[11] Rufer et al. speculate that mutation of serine to the bulkier, hydrophobic leucine alters a critical interaction with nearby Phe117, ultimately modifying the position and environment of the catalytically important residues Trp116 and Arg498, reducing enzyme activity.[12]

- Pro50His This proline is 23 residues from the active site, and is located right below the hydrophobic membrane insert in the active CPT II enzyme.[6] Hsiao et al. speculate that this mutation indirectly compromises the association between CPT II and the inner mitochondrial membrane and disturbs the shuttling of the palmitoylcarnitine substrate into the active site of the enzyme.[6]

Enzyme activity and disease severity

The clinical significance of the biochemical consequences that result from the genetic abnormalities in patients with CPT II Deficiency is a contested issue. Rufer et al. support the theory that there is an association between level of enzyme activity and clinical presentation.[12] Multiple research groups have transfected COS-1 cells with different CPT II mutations and found varying levels of reduction in enzyme activity compared with controls: Phe352Cys reduced enzyme activity to 70% of wild-type, Ser113Leu reduced enzyme activity to 34% of wild-type, and several severe mutations reduced activity to 5-10% of wild-type.[5]

However, most researchers are reluctant to accept the existence of a causal relationship between enzyme functionality and clinical phenotype.[5] Two groups[13][14] have recently reported a limited correlation (lacking in statistical significance) between the genotypic array and the clinical severity of the phenotype in their patient cohorts. There is a need for further explorations of this topic in order to fully assess the biochemical ramifications of this enzymatic deficiency.

The rate of long-chain fatty acid oxidation in CPT II-deficient patients has been proposed to be a stronger predictor of clinical severity than residual CPT II enzyme activity. For example, one study found that although the level of residual CPT II activity in adult versus infantile onset groups overlapped, a significant decrease in palmitate oxidation was noted in the infantile group when compared to the adult group.[15] This group concluded that both the type and location of CPT2 mutation in combination with at least one secondary genetic factor modulate the long-chain fatty acid flux and, therefore, the severity of the disease.[15]

Pathophysiology

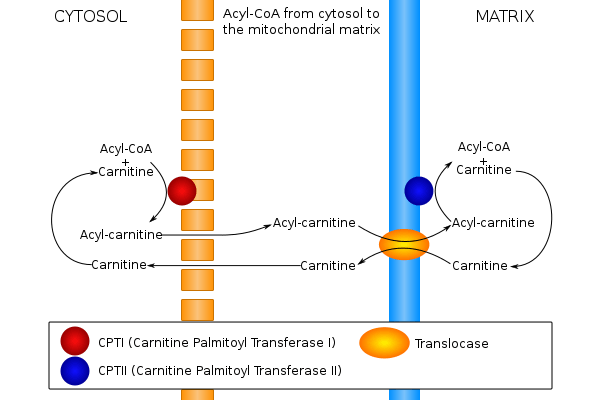

Carnitine is a hydrophilic natural substance acquired mostly through dietary meats and dairy products and is used by cells to transport hydrophobic fatty acids.[16] The "carnitine shuttle"[17] is composed of three enzymes that utilize carnitine to facilitate the import of hydrophobic long-chain fatty acids from the cytosol into the mitochondrial matrix for the production of energy via β-oxidation.[18]

- Carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT I) is localized to the outer mitochondrial membrane and catalyzes the esterification reaction between carnitine and palmitoyl-CoA to produce palmitoylcarnitine. Three tissue-specific isoforms (liver, muscle, brain) have been identified.

- Carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase (CACT) is an integral inner mitochondrial membrane protein that transports palmitoylcarnitine from the intermembrane space into the matrix in exchange for a molecule of free carnitine that is subsequently moved back out of the mitochondria into the cytosol.

- Carnitine palmitoyltransferase II (CPT II) is a peripheral inner mitochondrial membrane protein ubiquitously found as a monomeric protein in all tissues that oxidize fatty acids.[11] It catalyzes the transesterification of palmitoylcarnitine back into palmitoyl-CoA which is now an activated substrate for β-oxidation inside the matrix.

Molecular genetics

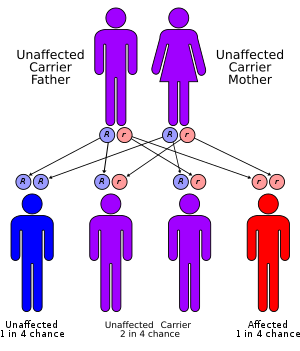

CPT II deficiency has an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance.[13] CPT2 is the gene that encodes the CPT II enzyme, and it has been mapped to chromosomal locus 1p32.[19] This gene is composed of 5 exons that encode a protein 658 amino acids in length.[13] To date, sixty disease-causing mutations within the coding sequence of CPT2 have been reported in the literature, of which 41 are thought to result in amino acid substitutions or deletions at critical residues.[5]

Amino acid consequences of some reported mutations

- Ser113Leu (338C>T) is the most common mild mutation observed in adult cases, it has an observed allelic frequency of 65% in adult cases,[13] and both homozygous and heterozygous cases have been documented.

- Pro50His (149C>A) is also relatively common in the adult form, with an allelic frequency of 6.5%.[20]

- Arg161Trp, Glu174Lys and Ile502Thr are other homozygous mild mutations associated with the adult form [5]

- Arg151Gln and Pro227Leu are examples of severe homozygous mutations that have been associated with the mutisystemic infantile/neonatal form of the disorder.[5]

- The 18 known severe mutations that result in prematurely truncated proteins lack residual CPT II activity are associated with the neonatal onset and are likely incompatible with life in most circumstances.[5]

- Val368Ile and Met647Val are polymorphisms have been linked to CPT II deficiency.[5] These genetic abnormalities alone do not directly cause the disorder, but they seem to exacerbate the reduction in enzymatic efficiency when combined with one or more primary CPT2 mutations.[20]

Recent research[15] found that mutations associated with a specific disease phenotype segregated to specific exons. In this study, infantile-onset cases had mutations in exon 4 or 5 of the CPT2 gene, while adult-onset cases had at least one mutation in exon 1 and/or exon 3. This group suggested that Ser113Leu (exon 3) and Pro50His (exon 1) might confer some sort of protective advantage against the development of the severe infantile phenotype in patients predisposed to develop the adult form of the disorder, since these two mutations have never been identified in cases of compound heterozygous infantile cases.[15] In support of this theory, an independent group reported two cases where mutations that have been shown to cause the infantile (Arg151Gln) or neonatal (Arg631Cys) forms when homozygous instead were associated with the milder, adult-onset phenotype when present as compound heterozygous mutations with Ser113Leu as the second mutation.[13]

Diagnosis

- Tandem mass spectrometry: non-invasive, rapid method; a significant peak at C16 is indicative of generalized CPT II deficiency[21][22]

- Genetic testing and carrier testing to confirm deficiency using a skin enzyme test.[23] Pregnant women can also undergo testing via amniocentesis.

- Enzymatic activity studies in fibroblasts and/or lymphocytes

- Laboratory findings: most patients have low total and free carnitine levels and high acylcarnitine:free carnitine ratios. Adult patients often have serum and/or urine screen positive for the presence of myoglobin and serum creatine kinase and transaminase levels 20-400x higher than normal levels during an attack.[20] Signs of metabolic acidosis and significant hyperammonemia have been reported in infantile and neonatal cases.[20][16]

Treatment

Standard of care for treatment of CPT II deficiency commonly involves limitations on prolonged strenuous activity and the following stipulations:

- The medium-chain fatty acid triheptanoin appears to be an effective therapy for adult-onset CPT II deficiency.

- Restriction of lipid intake, increased carbohydrate intake[24]

- Avoidance of fasting situations

- Glucose infusions during infections to prevent catabolism

- Avoidance of valproic acid, ibuprofen, diazepam, and general anesthesia [24]

- Dietary modifications including replacement of long-chain with medium-chain triglycerides supplemented with L-carnitine

- Rigorous meal schedule[23]

- Avoidance of rigorous exercise.[23]

See also

- Carnitine O-palmitoyltransferase

- Carnitine palmitoyltransferase I deficiency

- Fasciculation

- Myokymia

- Primary carnitine deficiency

References

- Research, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Military Nutrition; Marriott, Bernadette M. (1994). The Role of Carnitine in Enhancing Physical Performance. National Academies Press (US).

- "Carnitine palmitoyltransferase II deficiency, lethal neonatal (Concept Id: C1833518) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- Reference, Genetics Home. "CPT II deficiency". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- Sigauke, Ellen; Rakheja, Dinesh; Kitson, Kimberly; Bennett, Michael J. (November 2003). "Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase II Deficiency: A Clinical, Biochemical, and Molecular Review". Laboratory Investigation. 83 (11): 1543–1554. doi:10.1097/01.LAB.0000098428.51765.83. ISSN 1530-0307. PMID 14615409.

- Isackson PJ, Bennett MJ, Vladutiu GD (December 2006). "Identification of 16 new disease-causing mutations in the CPT2 gene resulting in carnitine palmitoyltransferase II deficiency". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 89 (4): 323–31. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.08.004. PMID 16996287.

- Hsiao Y, Jogl G, Esser V, Tong L (2006). "Crystal structure of rat carnitine palmitoyltransferase II (CPT-II)". Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 346 (3): 974–80. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.006. PMC 2937350. PMID 16781677.

- Finocchiaro G; et al. (1991). "cDNA cloning, sequence analysis, and chromosomal localization of the gene for human carnitine palmitoyltransferase". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 88 (2): 661–5. Bibcode:1991PNAS...88..661F. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.2.661. PMC 50872. PMID 1988962.

- Nic, Bhaird N; et al. (1993). "Comparison of the active sites of the purified carnitine acyltransferases from peroxisomes and mitochondria by using a reaction-intermediate analogue". Biochem J. 294 (3): 645–51. doi:10.1042/bj2940645. PMC 1134510. PMID 8379919.

- Ramsay R; et al. (2001). "Molecular enzymology of carnitine transfer and transport". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology. 1546 (1): 21–43. doi:10.1016/s0167-4838(01)00147-9. PMID 11257506.

- Wu D; et al. (2003). "Structure of Human Carnitine Acetyltransferase: Molecular Basis For Fatty Acyl Transfer". J Biol Chem. 278 (15): 13159–65. doi:10.1074/jbc.m212356200. PMID 12562770.

- Sigauke E; et al. (2003). "Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase II Deficiency: A Clinical, Biochemical, and Molecular Review". Laboratory Invest. 83 (11): 1543–54. doi:10.1097/01.LAB.0000098428.51765.83. PMID 14615409.

- Rufer A; et al. (2006). "The Crystal Structure of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 2 and Implications for Diabetes Treatment". Structure. 14 (4): 713–23. doi:10.1016/j.str.2006.01.008. PMID 16615913.

- Corti S, Bordoni A, Ronchi D, et al. (March 2008). "Clinical features and new molecular findings in Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase II (CPT II) deficiency". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 266 (1–2): 97–103. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2007.09.015. PMID 17936304.

- Wieser T; et al. (2003). "Carnitine palmitoyltransferase II deficiency: molecular and biochemical analysis of 32 patients". Neurology. 60 (8): 1351–3. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000055901.58642.48. PMID 12707442. S2CID 14849280.

- Thuillier L et al. (2003). Correlation between genotype, metabolic data, and clinical presentation in carnitine palmitoyltransferase 2 (CPT2) deficiency. Hum Metab, 21: 493-501.

- Longo N, Amat, San Filippo C, Pasquali M (2006). "Disorders of Carnitine Transport and the Carnitine Cycle". Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 142 (2): 77–85. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.30087. PMC 2557099. PMID 16602102.

- Nelson DL and Cox MM (2005). "Fatty Acid Catabolism" in Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry, 4th Ed. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company, 631-55.

- Kerner J, Hoppel C (June 2000). "Fatty acid import into mitochondria". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1486 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00044-5. PMID 10856709.

- Gellera C; et al. (1994). "Assignment of the human carnitine palmitoyltransferase II gene (CPT1) to chromosome 1p32". Genomics. 24 (1): 195–7. doi:10.1006/geno.1994.1605. PMID 7896283.

- Bonnefont JP; et al. (2004). "Carnitine palmitoyltransferases 1 and 2: biochemical, molecular and medical aspects". Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 25 (5–6): 495–520. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2004.06.004. PMID 15363638.

- Brivet M et al. (1999). Defects in activation and transport of fatty acids. J Inher Metab Dis, 22: 428-441.

- Rettinger A et al. (2002). Tandem Mass Spectrometric Assay for the Determination of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase II Activity in Muscle Tissue. Analyt Biochem, 302: 246-251.

- "NEWBORN SCREENING". www.newbornscreening.info. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Stephens K, Amemiya A, Wieser T (1993). "Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase II Deficiency". PMID 20301431. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

This article incorporates public domain text from The U.S. National Library of Medicine