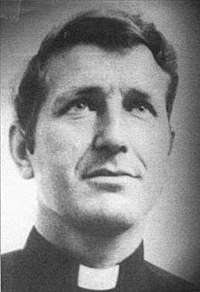

Carlos Mugica

Carlos Mugica (October 7, 1930 – May 11, 1974) was an Argentine Roman Catholic priest and activist.

Life and times

Early life

Carlos Francisco Sergio Mugica was born in Buenos Aires, in 1930, into a privileged background. His father, Adolfo Mugica, had been one of the founders of the National Democratic Party (opponents of suffrage activist and populist President Hipólito Yrigoyen), and his mother was Carmen Echagüe – herself born to one of Argentina's premier landowners. Mugica was the only one of seven siblings to have completed both his primary and secondary education in secular schools, and he graduated from the prestigious public college preparatory school, the Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires.

Mugica enrolled at the University of Buenos Aires in 1949 and was accepted into its law school; but in 1952, following a year in Europe, he resolved to enter the priesthood. He entered the Villa Devoto Seminary and in 1954 was assigned to the Parish of Saint Rose of Lima, from where he began ministering to the faithful in tenements in Buenos Aires' working-class Constitución area. He contributed articles and commentary to the ecclesiastical Seminario magazine from 1957 and in 1959, was ordained as a priest by the local Roman Catholic Church.

The priesthood and work among the poor

He spent most of 1960 in a parish in Chaco Province (one of Argentina's least developed), and was then appointed vicar for the Archbishop of Buenos Aires, Antonio Cardinal Caggiano. Cardinal Caggiano assigned his new vicar to a number of both Catholic and secular institutions, including the University of Buenos Aires, where he sponsored a 1965 symposium, "Dialogue between Catholics and Marxists." He taught as Professor of Theology, Child Psychology and Law in the prominent Universidad del Salvador, and became known for his weekly homilies on the Municipal Radio station. Mugica, however, also accepted the post of chaplain at the Paulina de Mallinkrodt School – a charitable institution within the slum adjacent to the city's port.

Mugica became a regular guest at the leftist Young Catholic Students organization (JEC), with whom he worked in a rural Santa Fe Province mission. A number of the JEC's membership, however, formed the violent Montoneros organization in 1968, and Mugica took some distance from these individuals, though he stopped short of breaking with them entirely. He was increasingly at odds with conservatives both in the University of Buenos Aires faculty (notably executive and Agricultural Law Professor José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz) and in the local archdiocese (particularly Bishop Juan Carlos Aramburu, who increasingly managed the aging Cardinal Caggiano's activities). These frictions were exacerbated by Mugica's 1967 mission to Bolivia for the sake of recovering revolutionary Che Guevara's remains.

A Third World priest

He stayed in Paris in support of the historic May 1968 protests. During that stay, he visited Argentina's exiled populist leader, Juan Perón, in his Madrid home. Perón, who at the time was occupied with cultivating alliances with the far left in Argentina, spent ten days in Cuba with Father Mugica who, on his return to Paris, joined the Movement of Priests for the Third World.

Mugica's growing involvement in politics led to his replacement at the Mallinkrodt school, whereby he obtained an appointment in the slum's new "Christ the Worker" Chapel, as well as Cardinal Caggiano's ordainment for the post. Continuing to teach university classes, he also served as vicar to the San Francisco Solano Parish in Buenos Aires' working-class Villa Luro neighborhood. His continued activism as a Third World Priest earned Bishop Armaburu's growing opposition, however, and in 1970, the Bishop banned the organization in the archdiocese. These differences reached a flash point when a fellow JEC priest, Father Alberto Carbone, was detained on charges of complicity in the Montoneros' murder of former President Pedro Aramburu. Mugica increasingly became a target, being regularly criticized in more conservative Argentine newspapers for his "justification of violence," as well as being put under surveillance by State Intelligence.

He defied orders by presiding over the September 1970 funerals of a number of executed Montoneros figures, which led to his suspension for 30 days by Bishop Aramburu. Following the suspension, Aramburu began actively pressing Mugica to renounce his vows, and he began taking increasingly intricate steps to conceal his whereabouts at night. Mugica improvised makeshift quarters at his parents' Recoleta district apartment building; but on July 2, 1971, a bomb exploded at the address. He then divided his time between the port-area slum and Monasterio Benedictino Santa María, Friar Mamerto Menapace's Benedictine monastery in Los Toldos (a pampas town well known for being the birthplace of former first lady Eva Perón). During a press conference following the blast, he declared that:

Nothing nor anyone will impede me from serving Christ and his Church by fighting alongside the poor for their liberation. If the Lord shall grant me the privilege – which I don't deserve – of losing my life in this endeavor, I shall be at His disposal.

Distancing from the Clergy and Perón

His sermons at the Christ the Worker Chapel enjoyed growing popularity, and were often visited by politicians, football players and other celebrities. The chapel received an impromptu visit on December 6, 1972, by Juan Perón, who had been allowed to temporarily return to Argentina by President Alejandro Lanusse ahead of upcoming elections. Within Perón's Justicialist Party, Mugica was perhaps closest to Dr. Héctor Cámpora, a left-leaning dentist and longtime advisor to Perón whom the aging leader made the party's nominee; Cámpora offered Mugica a candidacy for a seat in Congress, which he refused. Peronists won the 1973 election handily, and though Cámpora took office on May 25, Perón was the new government's principal figure. His ongoing manipulation of both the left and the right in his movement was illustrated by his allowing Cámpora to name Father Mugica as an unpaid, senior consultant to the powerful Minister of Social Welfare – a post Perón filled with his personal secretary and leading far-right voice, José López Rega.

López Rega used the important cabinet position (and its control of 30% of the national budget) to organize and arm his Argentine Anticommunist Alliance (Triple A). The resulting return of revenge killings between the Triple A against the left and the violence that resulted (the Montoneros' violence being more strategic, such as bombing buildings of transnational corporations funding the AAA and Right-wing violence) led Mugica to leave his government post, as well as to break with the Montoneros, by December 1973. He became the subject of increasingly heated political debate, and numerous unauthorized compilations of his works appeared – with each arranging his prolific past articles in the order most amenable to their agenda. Mugica's repudiation of these did little to deter the practice, and he accepted RCA Victor's offer to create a recorded version of his recently written Mass for the Third World. The reading, set to indigenous music and chorus, was ordered destroyed by the government of Isabel Perón in early 1975, however.[1]

Assassination

Amid frequent death threats and warnings of his imminent defrocking by Bishop Aramburu, he retreated briefly to Los Toldos in April. He then returned to Buenos Aires, where he resumed his daily schedule of services. Following Saturday morning services on May 11 at the San Francisco Solano Parish, Rodolfo Almirón, an operative of the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance (AAA), discharged five shots of a Mac-10 pistol into Father Mugica; he did not immediately die from his wounds and was rushed to a nearby hospital, where his last words were to a nurse: Now more than ever, we must be with the people.[2]

References

- "El Padre Carlos Mugica y su Misa para el Tercer Mundo, un disco secuestrado por la dictadura militar argentina antes de su distribución. | audio.urcm.net". audio.urcm.net. Retrieved 2016-01-13.

-

"CARLOS MUGICA - ANIVERSARIO de su MARTIRIO". La Fogata Digital (in Spanish).

Ahora más que nunca tenemos que estar junto al pueblo