Cardiac rehabilitation

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is a branch of rehabilitation medicine or physical therapy dealing with optimizing physical function in patients with cardiac disease or recent cardiac surgeries.

Cardiac rehabilitation is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as "The sum of activity and interventions required to ensure the best possible physical, mental, and social conditions so that patients with chronic or post-acute cardiovascular disease may, by their own efforts, preserve or resume their proper place in society and lead an active life".[1]

Cardiac rehabilitation is a comprehensive exercise, education, and behaviour modification program with a goal of helping patients restore and maintain optimal health while helping to reduce the risk of future heart problems.[2]

CR services can be provided during hospitalization for the event,[3] in an outpatient setting[4] or remotely using telephone or new technology.[5] While the "glue" of cardiac rehabilitation is exercise, programs are evolving to become comprehensive prevention centers where all aspects of preventive cardiology care are delivered. This includes nutritional therapies, weight loss programs, management of lipid abnormalities with diet and medication, blood pressure control, diabetes management, and stress management. CR exercise and prevention programs are supported by the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology.

Procedure

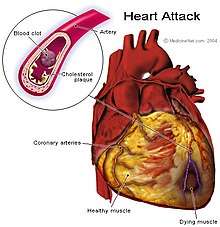

Patients typically enter cardiac rehabilitation in the weeks following an acute coronary event such as a myocardial infarction (heart attack), coronary artery bypass surgery, with a diagnosis of heart failure,[6] replacement of a heart valve, percutaneous coronary intervention (such as coronary stent placement), placement of a pacemaker, or placement of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator.[4] A 2017 Cochrane review showed similar short-term benefits from home- and centre-based rehabilitation, though there was not sufficient data to know whether this is sustainable over time.[7]

Inpatient program

Patients receiving CR in the hospital after surgery are usually able to begin within a day or two. First steps include simple motion exercises that can be done sitting down, such as lifting the arms and legs. Heart rate is monitored and continues being monitored as the patient begins to walk.[3]

Outpatient program

Most patients wishing to participate in outpatient CR are able to begin within 4–6 weeks after surgery. In order to participate in an outpatient program, the patient must first obtain a physician's referral.[8] Participation typically begins with an intake evaluation that includes measurement of cardiac risk factors such as lipid measures, blood pressure, body weight, and smoking status. An exercise stress test is usually performed both to determine if exercise is safe and to allow for the development of a custom exercise program. During exercise, the patient's heart rate and blood pressure are monitored to check the intensity of activity.[4]

Short and long-term risk factors and goals are established, and patients are closely monitored by a "case-manager" who may be a cardiac-trained Registered Nurse, Physiotherapist, respiratory therapist, or an exercise physiologist. A dietitian helps create a healthy eating plan, and a counselor may help to alleviate stress or, for smokers, may give counseling on how to quit.[4]

The duration of the program varies from patient to patient and can range from six months to several years.[4] Even after CR is finished, there are long-term maintenance programs that should not be minimized, as benefits are maintained only with long-term adherence.

Lifestyle changes

Obesity

Weight loss is a tool used to aid in cardiac rehabilitation.[9]

There is a strong correlation between obesity and cardiovascular disease. Obesity is associated with excessive fat accumulation in the body, which can inhibit bodily functions, such as blood flow through veins and arteries.[10] When adipose tissue expands, the number of pro-inflammatory cytokines also increases. As the name suggests, cytokines have an inflammatory reaction to this, in which they induce the build-up of plaques in veins and arteries.[11]

Obesity stems from a diet high in saturated fats, processed food and excess alcohol. These have all been shown to increase the inflammatory response to produce the plaque-building cytokines in the blood. In a randomized meta-analysis, scientists found a 47% reduction in mortality, following a change in lifestyle, regarding diet.[2]

Another factor in obesity is sedentary lifestyle. Physical activity is associated with a plethora of benefits, especially blood flow and inhibition of plaque build-up. In a meta-analysis of 11 different exercises, it was found that there was a 24% reduction in myocardial infarction. This study was based on the recommended guidelines of moderately-intense exercise for 30 minutes per day and 5 days per week.[2]

Underuse

Participation in cardiac rehabilitation is associated with a 25% decrease in overall mortality over three years.[12][13]

Cardiac rehabilitation services are significantly underused in the United States, with only 19–29% of patients with eligible cardiac diagnoses participating. Underuse is related to many factors, including lack of available programs nearby and low referral rates by physicians, who often focus more attention on better reimbursed cardiac-intervention procedures than on long-term lifestyle treatments.[14][15] With a contemporary focus on the cost-effectiveness of medical interventions, CR programs are well-positioned to assume a more prominent role in the long-term care of patients with coronary heart disease.[16]

Benefits

The use of cardiac rehabilitation is well established in the scientific community. Excerise based programs have been shown to improve cardiac fitness as well as the microvacular response.[17] A Cochrane Review of 147 studies demonstrated that for myocardial infarction and heart failure patients, exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation improves quality of life and reduces readmission rates. However, there was no benefit in mortality.[18][19] There appears to be no difference in outcomes between inpatient and outpatient programs. Rehabilitation programs that only have an educational or psychological component have not been shown to be effective. Another Cochrane Review of six randomised controlled trials in adults with atrial fibrillation found that exercise-based rehabilitation may improve physical exercise capacity, but there was no effect on health-related quality of life. Due to the limited number of trials, the authors could not estimate the impact on mortality or serious adverse events.[20]

References

- WHO Expert Committee on Rehabilitation after Cardiovascular Diseases, with Special Emphasis on Developing Countries. Rehabilitation after cardiovascular diseases, with special emphsis on developing countries : report of a WHO expert committee. Geneva. ISBN 9241208317. OCLC 28401958.

- Mampuya, Warner M. (2012-01-31). "Cardiac rehabilitation past, present and future: an overview". Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy. 2 (1): 38–49–49. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2012.01.02. ISSN 2223-3660. PMC 3839175. PMID 24282695.

- Zarret, Barry L.; Moser, Marvin; Cohen, Lawrence S. (1992). "Chapter 28" (PDF). Yale University School of Medicine Heart Book. Yale University School of Medicine. pp. 349–358 [351]. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

Cardiac rehabilitation begins during hospitalization, not after discharge. Today’s heart-attack patient who is free of complications is likely to be up and about in a day or two.

- "What is Cardiac Rehabilitation?". American Heart Association. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- Phillips, P (2014). "Telephone follow-up for patients eligible for cardiac rehab: A systematic review". British Journal of Cardiac Nursing. 9 (4): 186–97. doi:10.12968/bjca.2014.9.4.186.

- Long, Linda; Mordi, Ify R; Bridges, Charlene; Sagar, Viral A; Davies, Edward J; Coats, Andrew JS; Dalal, Hasnain; Rees, Karen; Singh, Sally J; Taylor, Rod S (2019). "Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with heart failure". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD003331. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003331.pub5. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 6492482. PMID 30695817.

- Anderson, Lindsey; Sharp, Georgina A; Norton, Rebecca J; Dalal, Hasnain; Dean, Sarah G; Jolly, Kate; Cowie, Aynsley; Zawada, Anna; Taylor, Rod S (2017-06-30). "Home-based versus centre-based cardiac rehabilitation". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD007130. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007130.pub4. PMC 4160096. PMID 28665511.

- "Cardiac Rehabilitation". Washington Hospital Healthcare System. Archived from the original on 14 October 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- Ades, Philip A.; Savage, Patrick D.; Harvey-Berino, Jean (2010). "The Treatment of Obesity in Cardiac Rehabilitation". Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 30 (5): 289–298. doi:10.1097/hcr.0b013e3181d6f9a8. ISSN 1932-7501. PMC 2917500. PMID 20436355.

- "Fact Sheet: Health Disparities in Obesity". PsycEXTRA Dataset. 2011. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- Carbone, Salvatore; Canada, Justin M; Billingsley, Hayley E; Siddiqui, Mohammad S; Elagizi, Andrew; Lavie, Carl J (May 2019). "

Obesity paradox in cardiovascular disease: where do we stand?

". Vascular Health and Risk Management. 15: 89–100. doi:10.2147/vhrm.s168946. ISSN 1178-2048. - Oldridge, Neil B. (1988-08-19). "Cardiac Rehabilitation After Myocardial Infarction". JAMA. 260 (7): 945–50. doi:10.1001/jama.1988.03410070073031. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 3398199.

- Witt, Brandi J.; Jacobsen, Steven J.; Weston, Susan A.; Killian, Jill M.; Meverden, Ryan A.; Allison, Thomas G.; Reeder, Guy S.; Roger, V. éronique L. (2004-09-01). "Cardiac rehabilitation after myocardial infarction in the community". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 44 (5): 988–996. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.062. ISSN 0735-1097.

- Cortés, Olga; Arthur, Heather M. (February 2006). "Determinants of referral to cardiac rehabilitation programs in patients with coronary artery disease: A systematic review". American Heart Journal. 151 (2): 249–256. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.034. ISSN 0002-8703.

- Thomas, Randal J.; King, Marjorie; Lui, Karen; Oldridge, Neil; Piña, Ileana L.; Spertus, John; Bonow, Robert O.; Estes, N. A. Mark; Goff, David C. (2007-10-02). "AACVPR/ACC/AHA 2007 Performance Measures on Cardiac Rehabilitation for Referral to and Delivery of Cardiac Rehabilitation/Secondary Prevention Services: Endorsed by the American College of Chest Physicians, American College of Sports Medicine, American Physical Therapy Association, Canadian Association of Cardiac Rehabilitation, European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, Inter-American Heart Foundation, National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 50 (14): 1400–1433. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.033. ISSN 0735-1097.

- "2005 Nutrition and Dietetics". Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2005.

- Louwies, T (2019). "Microvascular reactivity in rehabilitating cardiac patients based on measurements of retinal blood vessel diameters". Microvascular Research. 124: 25–29. doi:10.1016/j.mvr.2019.02.006. PMID 30807772.

- Anderson Lindsey (2014). "Cardiac rehabilitation for people with heart disease: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews". Reviews (12): CD011273. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011273.pub2. hdl:10871/19152. PMID 25503364.

- Anderson, Lindsey; Sharp, Georgina A.; Norton, Rebecca J.; Dalal, Hasnain; Dean, Sarah G.; Jolly, Kate; Cowie, Aynsley; Zawada, Anna; Taylor, Rod S. (2017). "Home-based versus centre-based cardiac rehabilitation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD007130. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007130.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 4160096. PMID 28665511.

- Risom, Signe S.; Zwisler, Ann-Dorthe; Johansen, Pernille P.; Sibilitz, Kirstine L.; Lindschou, Jane; Gluud, Christian; Taylor, Rod S.; Svendsen, Jesper H.; Berg, Selina K. (2017-02-09). "Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with atrial fibrillation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD011197. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011197.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6464537. PMID 28181684.

References

- Ades PA. Cardiac Rehabilitation and Secondary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001 Sep 20;345(12):892-902.

- Suaya JA, Shepard DS, Normand SL, Ades PA, Prottas J, Stason WB. Use of cardiac rehabilitation by Medicare beneficiaries after myocardial infarction or coronary bypass surgery. Circulation. 2007 Oct 9;116(15):1653-62.

- Ayala C et al. Receipt of cardiac rehabilitation services among heart attack survivors—19 states and the District of Columbia. Morbid Mortality Weekly. 2003; 52:1072-1075