Campanian Ignimbrite eruption

The Campanian Ignimbrite eruption (CI, also CI Super-eruption) was a major volcanic eruption in the Mediterranean during the late Quaternary, classified at 7 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI).[1] The event has been attributed to the Archiflegreo volcano, the 13-kilometre-wide (8.1 mi) caldera of the Phlegraean Fields, located 20 km (12 mi) west of Mount Vesuvius under the western outskirts of the city of Naples and the Gulf of Pozzuoli, Italy.[2] Estimates of the date, magnitude and the amount of ejected material have varied considerably during several centuries of investigation. This applies to most significant volcanic events that originated in the Campanian Plain, as it is one of the most complex volcanic structures in the world. However, continued research, advancing methods and accumulation of volcanological, geochronological, and geochemical data has amounted to ever more precise dating.[3]

| Campanian Ignimbrite eruption | |

|---|---|

| |

| Volcano | Phlegraean Fields |

| Date | 37,330 BC |

| Type | Ultra-Plinian |

| Location | Naples, Campania, Italy 40.827°N 14.139°E |

| VEI | 7 |

Phlegraean Fields Location of eruption | |

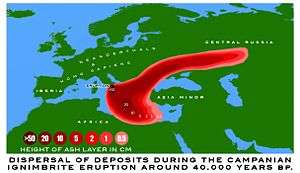

The most recent dating determines the eruption event at 39,280±110 years BP[4] and results of 3D Ash Dispersion Modelling published in 2012[5] concluded a dense-rock equivalent (DRE) of 300 km3 (72 cu mi) and emissions dispersed over an area of around 3,700,000 km2 (1,400,000 sq mi). The accuracy of these numbers is of significance for marine geologists, climatologists, palaeontologists, paleo-anthropologists and researchers of related fields as the event coincides with a number of global and local phenomena, such as widespread discontinuities in archaeological sequences, climatic oscillations and biocultural modifications.[6]

Etymology

The term Campanian refers to the Campanian volcanic arc located mostly but not exclusively in the region of Campania in southern Italy that stretches over a subduction zone created by the convergence of the African and Eurasian plates.[7] It should not be confused with the Late Cretaceous stage Campanian.

The word ignimbrite was coined by New Zealand geologist Patrick Marshall from Latin ignis (fire) and imber (shower)) and -ite. It means the deposits that form as a result of a pyroclastic eruption.[8]

Background

The Phlegraean Fields (Italian: Campi Flegrei "burning fields"[lower-alpha 1])[9] caldera is a nested structure with a diameter of around 13 km (8.1 mi).[10] It is composed of the older Campanian Ignimbrite caldera, the younger Neapolitan Yellow Tuff caldera and widely scattered sub-aerial and submarine vents from which the most recent eruptions have originated. The Fields sit upon a Pliocene - Quaternary Extensional domain with faults, that run North-East to South-West and North-West to South-East from the margin of the Apennine thrust belt. The sequence of deformation has been subdivided into three periods.[11]

Phlegraean Periods

- The First Period, which includes the Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption was the most decisive era in the Phlegraean Fields' geologic history. Beginning more than 40,000 years ago as the external caldera formed, subsequent caldera collapses and repeated volcanic activity took place within a limited area.[12]

- During the Second Period, the smaller Neapolitan Yellow Tuff eruption (Neapolitan Yellow Tuff or NYT) took place around 15,000 years ago.

- Eruptions of the Third Period occurred during three intervals between 15,000 and 9500 years ago, 8600 and 8200 years ago and from 4800 to 3800 years ago.[13]

The structure's magma chamber remains active as there apparently are solfataras, hot springs, gas emissions and frequent episodes of large-scale up- and downlift ground deformation (Bradyseism) do occur.[14][15]

In 2008 it was discovered that the Phlegraean Fields and Mount Vesuvius have a common magma chamber at a depth of 10 km (6.2 mi).[16]

The region's volcanic nature has been recognized since Antiquity, investigated and studied for many centuries. Methodical scientific research began in the late 19th century. The yellow tuff stone was extensively quarried for centuries, which left large underground cavities that served as aqueducts and cisterns for the collection of rain water.[17]

In 2016 Italian Volcanologists announced plans to drill a probe 3 km (1.9 mi) deep into the Phlegraean Fields several years after the 2008 Campi Flegrei Deep Drilling Project which had aimed to drill a 3.5 km (2.2 mi) diagonal borehole in order to bring up rock samples and install seismic equipment. The project was suspended in 2010 due to safety problems.[18]

Eruptive sequence

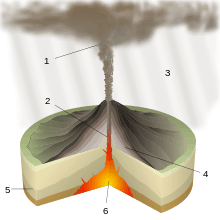

The CI eruption has been interpreted as the largest volcanic eruption of the past 200,000 years in Europe.[19] Tephra deposits indicate two distinct plume forming phases, a Plinian and a co-ignimbrite, characterized by multiple caldera-forming eruptions.[20]

Plinian phase

Evidence shows that the eruption was a single event lasting 2 to 4 days.[21] It was triggered by abrupt changes in composition, properties and physical state in the melt or overpressure in the magma chamber. The eruption started with phreatomagmatic explosions, followed by a Plinian eruption column, fed by simultaneous extraction of two magma layers. The resulting ash plume is estimated to have been 70 km (43 mi) high. As gradually an unstable pulsating column formed, fed only by the most evolved magma due to upward migration of the fragmentation surface, reduced magma eruption rate, and/or activation of fractures, the Plinian phase ended. Emissions consisted of pumice and dark colored volcanic rock (scoria). The mafic minerals cover smaller areas than the more acidic members, also indicating a decrease of explosivity over the course of the eruption. The eruption column caused a large pumice-fall deposit to the east of the source area.[22]

Pyroclastic density currents

The initial eruption was followed by a caldera collapse and a large pyroclastic flow, fed by the upper magma layer, a single flow unit with lateral variations in both pumice and lithic fragments, that covered an area of 30,000 km2 (12,000 sq mi). Currents that moved toward the North and the South overflowed 1,000-metre-high (3,300 ft) mountain ranges and crossed the Gulf of Naples over the sea, extinguishing all life within a radius of about 100 km (62 mi).[23][24] Textural and morphological features of the deposits, and areal distribution suggests that the eruption was of the type of highly expanded low-temperature pyroclastic cloud.

The pyroclastic sequence from base to top:

- densely welded ignimbrite and lithic-rich breccias

- sintered ignimbrite, low-grade ignimbrite and lithic-rich breccia

- lithic-rich breccia and spatter agglutinate (see Volcanic cone)

- low-grade ignimbrite[25][26]

Ignimbrite deposit

The ignimbrite is a gray, poorly to moderately welded, nearly saturated potassic trachyte, similar to many other trachytes of the Quaternary volcanic province of Campania. It consists of pumice and lithic fragments in a devitrified matrix that contains sanidine, lesser plagioclase rimmed by sanidine, two clinopyroxenes, biotite, and magnetite. The column collapse that generated the widespread ignimbrite deposit most likely occurred due to an increase of the Mass Eruption Rate (MER), (see Eruption column).[27]

The immediate area was completely buried by thick layers of pyroclastic fragments, volcanic blocks, lapilli and ash. Two thirds of Campania sank under a layer of tuff as much as 100 m (330 ft) thick. The greater ignimbrite deposit, mostly trachytic ash and pumice, covered an area of at least 7,000 km2 (2,700 sq mi), encompassing most of the southern Italian peninsula and the eastern Mediterranean region.[28][29]

Calculations of ash thickness measurements collected at 115 sites and a three dimensional ash dispersal model add up to a total amount of fallout material of 300 km3 of tephra across an area of 3,700,000 km2 (1,400,000 sq mi). Considering volume estimations of up to 300 km3 (72 cu mi) for the proximal pyroclastic density current deposits, the total bulk volume of the CI eruption is 680 km3 (160 cu mi) covering most of the eastern Mediterranean and ash clouds reaching as far as central Russia.[30][31]

Global impact

The event's recent dating at 39,280±110 years ago draws considerable scholarly attention as it marks a time interval characterized by biocultural modifications in western Eurasia and widespread discontinuities in archaeological sequences, such as the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition. At several archaeological sites of South-eastern Europe, the ash separates the cultural layers containing Middle Palaeolithic and/or Earliest Upper Palaeolithic assemblages from the layers in which Upper Palaeolithic industries occur. At some sites the CI tephra deposit coincides with a long interruption of paleo-human occupation.[32]

Effect on climate

The climatic importance of the eruption was tested in a three-dimensional sectional aerosol model that simulated the global aerosol cloud under glacial conditions. Authors calculate that up to 450 million kilograms (990 million pounds) of sulphur dioxide would have been accumulated into the atmosphere, driving down temperatures at least by 1 to 2 degrees Celsius (1.8-3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) for a period of 2 to 3 years. The Heinrich event 4 (H4), the name given to a cooling period, characterized by a break off of unusual large sections of ice from polar glaciers occurred around 40,000 years ago being well documented in the North Atlantic Ocean, although its impact on terrestrial areas is a matter of ongoing debate.[33]

Effect on living organisms

Sulphur dioxide and chloride emissions caused acidic rains, fluorine-laden particles become incorporated into plant matter, potentially inducing dental fluorosis, replete with eye, lung and organ damage in animal populations.[34]

Neanderthal demise

The eruption coincided also with the final decline of the Neanderthal in Europe. Environmental stress caused by the eruption has been invoked as a potential explanation for the extinction as well as discontinuities in Palaeolithic societies, although the climatic effects of the eruption alone are considered insufficient to account for the demise of the Neanderthals in Europe. The notion remains contested; nonetheless, some studies suggest that significant volcanic cooling during the period immediately after the eruption might have severely disturbed these already precarious populations.[35][36]

Island biodiversity

A joint study on the influence of the Late Quaternary climate change on island biodiversity has been published in 2016 in the Nature journal. This investigation on the consequences of abrupt climate changes for island biodiversity is apparently unprecedented. Established "island biogeographical models consider islands either as geologically static with biodiversity resulting from ecologically neutral immigration–extinction dynamics, or as geologically dynamic with biodiversity resulting from immigration–speciation–extinction dynamics influenced by changes in island characteristics over millions of years." Researchers argue that "climatic oscillations over short geological periods are likely to affect sea levels and cause huge changes in island size, isolation and connectivity, orders of magnitude faster than the geological processes of island formation..." Results suggest that "post-Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) changes in island characteristics, especially in area, have left a strong imprint on the present diversity of endemic species."[37]

Laschamp event

In 2012 the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences has published a study on likely causal connections between the Laschamp magnetic reversal and the eruption as "sediment cores from the Black Sea show that during this period a compass at the Black Sea would have pointed to the south instead of north." Evidence seems to be limited and the publication is no longer publicly available.[38]

See also

Notes

- Footnotes

- A term derived from Latin and Greek - indicating that the volcanic nature of the area has been well known since antiquity.

References

- Mastrolorenzo, Giuseppe; Palladino, Danilo M; Pappalardo, Lucia; Rossano, Sergio (March 5, 2016). "Probabilistic-Numerical assessment of pyroclastic current hazard at Campi Flegrei and Naples city: Multi-VEI scenarios as a tool for full-scale risk management - VEI 7 Campanian Ignimbrite extreme event". PLOS One. 12 (10): e0185756. arXiv:1603.01747. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1285756M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185756. PMC 5636126. PMID 29020018.

- "Campi Flegrei (Phlegrean Fields) volcano". VolcanoDiscovery. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- De Vivo, B. (2001). "New constraints on the pyroclastic eruptive history of the Campanian volcanic Plain (Italy)". Mineralogy and Petrology. 73 (1–3): 47–65. Bibcode:2001MinPe..73...47D. doi:10.1007/s007100170010.

- Fedele, Francesco G.; Giaccio, Biagio; Isaia, Roberto; Orsi, Giovanni (2003). Volcanism and the Earth's Atmosphere. Geophysical Monograph Series. 139. researchgate net Publishing. pp. 301–325. doi:10.1029/139GM20. ISBN 978-0-87590-998-1. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- Costa, A. (May 28, 2012). "Quantifying volcanic ash dispersal and impact of the Campanian Ignimbrite super-eruption" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 39 (10): n/a. Bibcode:2012GeoRL..3910310C. doi:10.1029/2012GL051605.

- "Campanian Ignimbrite volcanism, climate, and the final decline of the Neanderthals" (PDF). University of California–Berkeley. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- "Mount Vesuvius: Plate Tectonic Setting". geology com. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- "Story: Marshall, Patrick Page 1". New Zealand Biography. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. October 30, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- "flegreo". Garzantilinguistica. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- "Campi Flegrei volcano, Campania". SRV. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- "Phlegrean Fields, Italy". Volcano World Oregon. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- "Volcanic risk in Campi Flegrei : past, present, future". Scienza in rete. 2012-10-03. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- Rybar, J.; Stemberk, J.; Wagner, P. (2002-01-01). Landslides - Proceedings of the First European Conference on Landslides - edited by J. Rybar, J. Stemberk, P. Wagner. ISBN 9789058093936. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- "PHLEGRAEAN FIELDS VOLCANO". VolcanoTrek. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- "Bradyseism in the Flegrea Area". UNESCO. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- "Der unsichtbare Supervulkan". STUTTGARTER ZEITUNG. January 19, 2013. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- ""Naples, the Vesuvius and the Phlegraean Fields" by MalKo". rivista hyde park. August 21, 2013. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- "Italian Scientists to Drill into Active Supervolcano". Mysterious Universe. September 5, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- "Ancient Super-Eruption Larger Than Thought...About 39,000 years ago, it experienced the largest volcanic eruption that Europe has seen in the last 200,000 years". Live Science. June 21, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- Marti, Alejandro; Folch, Arnau; Costa, Antonio; Engwell, Samantha (February 17, 2016). "Reconstructing the plinian and co-ignimbrite sources of large volcanic eruptions: A novel approach for the Campanian Ignimbrite". Scientific Reports. Springer Nature. 6: 21220. Bibcode:2016NatSR...621220M. doi:10.1038/srep21220. PMC 4756320. PMID 26883449. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- "Campi Flegrei". University Roma. Archived from the original on December 25, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- Scarpati, Claudio; Perrotta, Annamaria (2016). "Stratigraphy and physical parameters of the Plinian phase of the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption" (PDF). Geological Society of America Bulletin. Università di Napoli. 128 (7–8): 1147. Bibcode:2016GSAB..128.1147S. doi:10.1130/B31331.1. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- "From the Bay of Naples to the River Don: the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption and the Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition in Eastern Europe" (PDF). Journal of Human Evolution. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- Fedele, Francesco G.; Giaccio, Biagio; Isaia, Roberto; Orsi, Giovanni (2002). "Ecosystem Impact of the Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption in Late Pleistocene Europe". Quaternary Research. 57 (3): 420–424. Bibcode:2002QuRes..57..420F. doi:10.1006/qres.2002.2331. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- Barberi, F.; Innocenti, F.; Lirer, L.; Munno, R.; Pescatore, T.; Santacroce, R. (1978). "The campanian ignimbrite: a major prehistoric eruption in the Neapolitan area (Italy)". Bulletin Volcanologique. 41 (1): 10. Bibcode:1978BVol...41...10B. doi:10.1007/BF02597680.

- Rosi, M.; Vezzoli, L.; Aleotti, P.; De Censi, M. (1996). "nteraction between caldera collapse and eruptive dynamics during the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption, Phlegraean Fields, Italy". Bulletin of Volcanology. 57 (7): 541. Bibcode:1996BVol...57..541R. doi:10.1007/BF00304438.

- "The Campanian IgnimbrMOBILITY OF A LARGE-VOLUME PYROCLASTIC FLOW--EMPLACEMENT OF THE CAMPANIAN IGNIMBRITE, ITALY". University of California, Santa Barbara. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- Rosi, M.; Vezzoli, L.; Aleotti, P.; De Censi, M. (1996). "Interaction between caldera collapse and eruptive dynamics during the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption, Phlegraean Fields, Italy". Bulletin of Volcanology. 57 (7): 541. Bibcode:1996BVol...57..541R. doi:10.1007/BF00304438.

- "Eine extrem kurze Umpolung des Erdmagnetfeldes, Klimaschwankungen und ein Supervulkan ...vor 39400 Jahren, in den untersuchten Sedimenten dokumentiert. Die Asche dieses Ausbruchs, bei dem etwa 350 Kubik-Kilometer Gestein und Lava ausgeworfen wurden..." (in German). Informationsdienst Wissenschaft e. V. / Archaeology and Prehistory. October 16, 2012. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- Engwell, S. L.; Sparks, R. S.; Carey, S.; Aspinall, W. (2011). "The Campanian Ignimbrite eruption: inferring eruption characteristics from distal submarine deposits". AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. 51: V51F–2565. Bibcode:2011AGUFM.V51F2565E.

- "Possibly more devastating than previously thought". MAX-PLANCK-GESELLSCHAFT, MÜNCHEN. June 20, 2013. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- "Heinrich event 4 characterized by terrestrial proxies in southwestern Europe" (PDF). clim past net. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- Black, Benjamin A.; Neely, Ryan R.; Manga, Michael (February 11, 2015). "Campanian Ignimbrite volcanism, climate, and the final decline of the Neanderthals". Geology. 43 (5): 411–414. Bibcode:2015Geo....43..411B. doi:10.1130/G36514.1.

- Schultz, Colin (June 18, 2012). "Italian super-eruption larger than thought". Eos Transactions. phys org. 93 (30): 298–299. Bibcode:2012EOSTr..93X.298S. doi:10.1029/2012EO300025. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- "What Are Those Darned Neanderthals Up to Now?". Anthropology in practice. October 11, 2010. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- "Did a Volcanic Eruption Kill Off the Neandertals?". Science for writers. March 25, 2015. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- Weigelt, Patrick (April 7, 2016). "Late Quaternary climate change shapes island biodiversity". Nature. 532 (7597): 99–102. Bibcode:2016Natur.532...99W. doi:10.1038/nature17443. PMID 27027291.

- "Scientists link magnetic reversal, climate change and super volcano to same time period". Evolutionary Leaps. October 17, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2016.