Callawassie Island

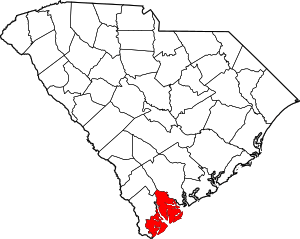

Callawassie Island is one of hundreds of barrier and sea islands in the southeast corner in the outer coastal plain, making up a portion of Beaufort County, South Carolina.[1]

| Native name: Callawassee, Callawasys, Calliwassee | |

|---|---|

A bridge to one of the greens on Callawassie Island | |

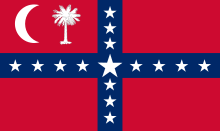

Beaufort County, South Carolina | |

| Geography | |

| Location | 176 Callawassie Drive Okatie, South Carolina 29909 |

| Coordinates | |

| Adjacent bodies of water | Colleton River,

Okatie River, Little Chechessee River, Callawassie Creek |

| Total islands | One |

| Area | 880 acres |

| Coastline | 5 mi (8 km)Rivers and tidal marshes |

| Highest elevation | 42 ft (12.8 m) |

| Administration | |

United States | |

| Additional information | |

| Official website | Public:

www.callawassieisland.com Members: www.callawassieisland.org |

Callawassie Island is centrally located 17 miles (27 km) southwest of Beaufort, South Carolina, 30 miles (48 km) northeast of Savannah, Georgia, and 275 miles (443 km) southeast of Atlanta, Georgia. The island is ten to twelve miles inland from the Atlantic Ocean in the estuarial system of the Port Royal Sound and is entirely surrounded by salt marshes and tidal creeks. Access to Callawassie is by a half mile causeway, one mile south of SC 170, or by boat via the deep waters of the Colleton River. The island's 880 acres (360 ha) are nestled at the confluence of the Callawassie Creek and the Little Chechessee, Okatie, and Colleton Rivers.[2] With five miles of waterfront on the salt marshes of the Port Royal Sound Basin, Callawassie Island is a major supporter of the state-of-the-art Maritime Center, run by the Port Royal Sound Foundation located on Lemon Island.

Archeological and site surveys reveal that the island was inhabited approximately 4,000 years ago.[3][4] In 1897, archeologists discovered prehistoric burial mounds. 102 sites have been identified and added to the National Register of Historic Places since then. The island is also home to the Callawassie Sugar Works (Sugar Mill Tabby Ruins), the only sugar mill ruins known to exist in South Carolina.[5][6][7]

In 2006, Callawassie Island was designated as South Carolina's first Community Wildlife Habitat (the 15th in the nation) with more than 200 residences being certified as Backyard Wildlife Habitats.[8]

The owners of 717 homes and home sites have access to 33 lagoons, three parks, one butterfly garden, and three rookeries, as well as a 27-hole golf course designed by Tom Fazio, six Har-Tru tennis courts, two pools, two clubhouses, two kayak launch docks, and three community fishing/crabbing docks, which also provide boat slips for both long-term and daily dockage.[9]

Geography and topography

The South Carolina coastal area known as the "Lowcountry" is geographically composed of: multiple sea islands, deep natural harbors, meandering estuaries which extend for miles inland, and tidal marshlands, populated by unique flora, as well as reptilian and aquatic ecosystems.

Adjacent islands include: Spring, Lemon, and Daws Islands which are settled as well as Wim's, Crane, and Rose Islands which are uninhabited. Surrounding waters include: the Colleton and Okatie Rivers and Little Chechessee and Callawassie Creeks.[2]

History

First settlers

The earliest history of Callawassie Island, dating back 4,000 years, is minimally revealed in multiple archeological and site surveys.[10] The Yamassee Indians gave Callawassie Island its name in the early 17th century and occupied the Lowcountry until their expulsion by the English.[9] The first archeological survey was conducted in 1897-98, and subsequent archeological and site surveys were conducted between the 1970s and 1990s.[11] Archeological discoveries of artifacts ranging from cooking utensils, hunting and construction implements, and human remains have been unearthed from 102 registered historic sites found on the island.[12][13] Multiple shell refuse mounds called "middens" provide evidence of one of the primary dietary items of early tribal settlers. Site survey discoveries of tabby constructed homes, farm houses, cabins, and a tabby works sugar mill built during the period between 1700 and the 1850s bear witness to early European settlers.[14]

Historic documents now located in area museums, as well as historic societies and local historians, provide an early glimpse of settlement history along the South Carolina coast, beginning in the 16th century. Trading ships from European nations, including Spain, France, England, and the Netherlands, sailed with the trade winds, following routes to Central America where they would trade and return home with enormous riches. Eventually trading vessels found their way to the coasts of Florida and South Carolina. Minor settlements sprang to life. Hunting, farming, and trading with local Indian tribes were primary settlement activities. Many settlements did not survive due to warring between European nations, violent uprisings by Indian tribes, and an inability to cope with the hostile environment. However, with every setback, came new explorations, settlements, and governing European nations.[15][16]

Callawassie Island, an 880-acre coastal island, received its earliest English settlers in 1711.[17] Over the next 120 years, ownership of Callawassie Island changed hands mostly through inheritance among well-to-do English families named Cochran, Heyward, Rhodes, and Hamilton. All figured prominently in early America either as land barons, governing authorities, and/or military leaders. Callawassie Island's acreage, fertile for planting, was largely dedicated to farming and livestock during this period, making way for successive cash crop industries in indigo and sea island cotton, which were in high demand by European trading nations. A small crop of sugar cane was attempted but failed due to climate conditions. The island's population was sparse, consisting of owner families and slaves who worked the farms.

Antebellum and Civil War years

During the Antebellum years leading up to the Civil War, the island's owners, the Kirk family, continued to prosper because of cotton even as they became active in southern rebellion causes that led to Secession from the Union.[18] In 1861 the Port Royal invasion by Union forces led to plundering and routine foraging for food and livestock throughout the Lowcountry, including Callawassie Island.[19]

Post Civil War years

At the conclusion of the Civil War, the Union seized Callawassie Island's acreage, and remaining assets, for promised redistribution to freedmen.[20] However, an elaborate scheme to take over ownership by William Wallace Burns, a prominent Union general, enabled him to maintain ownership for the next fifty years. Burns was motivated, along with other northern interests, by a vision of this area of the Lowcountry becoming "The Port Royal Railroad/Seaport" development complex, a vision that was put to rest only fifty years later by competing interests in Savannah, Georgia and Charleston, South Carolina.

General Burns was an absentee landlord assigning multiple leasing rights for the island's acreage to local area farmers over the next fifty years. Farmers by the names of Hodge, Vaigneur, Johnson, and Pinckney raised families, maintained livestock, and grew a variety of subsistence crops and cotton as a cash crop. Life on the island was simple, but far from easy, often resulting in death at an early age caused by: polluted waters, epidemics of infectious diseases, and occasional natural disasters including storms, drought, and earthquakes.[21]

The Great Storm of 1893

On August 27, 1893, "The Great Storm of 1893" (also known as the "1893 Sea Island hurricane") was a significant natural disaster striking near Savannah, Georgia, thus flooding Callawassie Island, destroying crops, livestock, and structures.[22] Although there was no loss of life on the island, the Lowcountry area was less fortunate, with the storm claiming in excess of 2,000 lives as its waters covered nearly 80% of Beaufort County.[23] After the Great Storm, Callawassie Island farmer Willie Pinckney secured loans to rebuild farms, maintain livestock, and grow crops. Willie became an area personality with leadership skills that were instrumental in reducing area disease through the construction of artesian wells that produced clear, unpolluted water, free of disease. Willie, then known as the "Sage of Okatie," continued to lease acreage and prosper from the island until 1917.

20th century

In 1917, the boll weevil struck South Carolina devastating cotton crops, and "King Cotton" was declared dead forever.[24] A modern era of invention throughout the United States left behind the old Southern ways of life on Callawassie Island. During 1917, wealthy New Jersey businessman Benedict Kuser purchased the island, announcing plans to develop Callawassie Island through modern truck farming. World War I intervened, and development plans turned toward commercial farming with the construction of homes for share cropper families and the construction of Kuser's own private estate. Sharecropper families – Padgett, Bennett, Cooler – lived and worked on Callawassie Island raising families, maintaining livestock, and growing a wide variety of crops while Ben Kuser, a very successful northern wildlife conservationist, brought a multitude of friends to the island for hunting and fishing outings. Lavish entertainment during the 1920s disappeared during the Great Depression of the 1930s, but the sharecropper families continued to flourish.

Ownership of the island changed twice during 1937, with it ending up in the hands of the Drexel family where it remained until they sold the island to timber interests in 1948. Sharecropper families continued to maintain and farm the island during this period.

Between 1948 and 1978, business entities with various profit motives owned Callawassie Island. They did not pursue land development activities and were eventually discouraged from pursuing these due to issues of cost, permitting, and protests of various projects by the local citizenry. One such protest involved a connector road routing that was planned directly across the island to support highway infrastructure for a large petrochemical plant to be built at Victoria Bluff on the Colleton River. The project was defeated by widely voiced protests, which reached the White House, demanding protection for and the preservation of local river and harbor water quality and wildlife.

Modern era

In 1978, a small group of Hilton Head investors purchased but did not develop the land, selling it to a developer when faced with high interest rates and other shelved projects. Between 1981 and 2002 developers continued ownership of Callawassie Island and developed the land as a gated, residential community consisting of 717 home sites, 33 lagoons, and multiple conservation and wildlife areas surrounded by a first class golf course and other amenities. In 2002, the developer sold all existing amenities to the Callawassie Island Members Club.

Callawassie Sugar Works

The Callawassie Sugar Works is a historically significant site containing the tabby (cement) ruins of two structures - the sugar mill base or foundation, and the boiling house - and archaeological evidence of a third structure, most likely the curing shed. The sugar works, constructed circa 1815-1818, was a complex for processing sugar cane into sugar.[25]

Archaeological and historical evidence suggests that the Callawassie Sugar Works was part of a larger settlement which included housing for slaves and possibly an overseer's house.[26] The settlement was mostly constructed soon after 1816 while the island was owned by James Hamilton, Jr. The architect/builder of the sugar works is unknown. It is conjectured that the sugar mill was built sometime within the next three years, based on plans similar to mill construction seen in the West Indies.

Research suggests that James Hamilton, Jr., (1786-1857) was most likely the developer of the Callawassie Sugar Works (circa 1816). He was the son of Major James Hamilton, an aide to General George Washington in the American Revolutionary War, and grandnephew of Thomas Lynch, Jr., a signatory of the Declaration of Independence. He served during the War of 1812. Through marriage, James Hamilton, Jr., was nephew-in-law of South Carolina's largest, and most prosperous rice planter, Nathaniel Heyward, and stepson-in-law of Savannah River investor Nicholas Cruger. These gentlemen shared close familial and professional relationships and entrepreneurial drive to develop and implement new industries such as sugar production. Hamilton had acquired several close and influential West Indian connections who were heavily involved in the Caribbean sugar trade. Hamilton sold the property and moved to Charleston, South Carolina in early 1819, leaving no documentation on the mill and its anticipated use. Apparently, the sugar works were still operational when it was abandoned, as ashes were left uncleared from the furnace.[27][28]

The Callawassie Sugar Works' construction appears to be based on observations made by Thomas Spalding.[29] It incorporated three principal components: a mill, boiling house, and curing shed. The footprint of the buildings suggests that the boiling house and curing shed were aligned in a "T" configuration (little remains of the curing shed). The remaining structures include exterior walls of the one-story buildings with the brick boiling train still evident in the mill. Primitive mills of this kind usually had a set of four kettles arranged in a line, the tops of the kettles being raised from the floor.[26]

Today, only the foundation of the mill and parts of the boiling house remain. There is no evidence, above or below ground, that the tabby mill base was ever enclosed within a permanent structure, even though the base survives in excellent condition. While the boiling pans, and the masonry that supported them, have disappeared, the boiling train bed, constructed of fire brick, is still intact, together with an ash pit and wall vents. The long tabby wall on the north side of the boiling house collapsed outward and retained enough integrity to enable theoretical reconstruction of the original layout of windows. Excavation of glass at the site suggests that the windows were glazed. Only tabby strip foundations remain of the curing shed, which was most likely timber framed. All machinery and mechanical equipment is gone. Despite the degradation of the sugar mill site over time, the remnants are still illustrative of sugar processing before the introduction of steam machinery in the late 1830s.[26]

The sugar mill ruins on Callawassie Island are featured as a "unique example of industrial tabby" and "the only one of its kind to exist in South Carolina." Tabby, referred to as "poor man's masonry", is a building substance created by mixing locally available materials, such as oyster shells, with equal parts, water, sand, and lime. The Spanish brought it to the New World before 1700. Shellfish remains available from aboriginal shell middens provided a plentiful source for tabby construction. Tabby wall construction involved up to six successive pours, each requiring a set of forms or molds. According to the National Park Service, the tabby remaining at the Callawassie Sugar Works: "appears to have been well compacted and meticulously cast."[30][31]

The Callawassie Sugar Works is one of the few remaining structures from this early period of sugar production along the Atlantic Coast. Sugar was one of the few agricultural commodities protected by a tariff, which levied three cents per pound duty on foreign raw sugar in 1816. This inspired wealthy planter entrepreneurs of the Georgia and South Carolina coastal areas to explore the viability of a local sugar industry. Despite Hamilton's entrepreneurial hopes, and Spalding's professional expertise, the growing conditions in the Low country of South Carolina were not ideally suited for the successful cultivation of sugar cane, which prefers a year-round temperature of 75 degrees Fahrenheit with at least 60 inches of rainfall. The sugar works on Callawassie Island is the only example of such an early enterprise in the South Carolina Low country. It was formally listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 27, 2014.[32]

Ecology and wildlife

Island ecology

Callawassie Island's location in a large expanse of salt marsh leaves the island open to the effects of wind and salt spray, giving it maritime-like vegetation.[33] The island is characterized by a diversity of natural communities, which include brackish marsh, maritime forest, maritime shrub thicket, salt flat, salt marsh, salt shrub thicket, and tidal freshwater marsh.[34][35]

Much of the salt marsh zone around the island is characterized by stands of two kinds of smooth spartina cord grass (tall and short).[36] The spartina cord grass provides essential nutrients, making the tidal marshes a breeding ground or nursery for countless species of mammals, birds, fish, and invertebrates. The salt marsh shrub thicket between the salt marsh and the maritime forests of the island include bayberry, wax myrtle, southern red cedar, and live oak.[37][38]

Despite the amount of surrounding salt water, Callawassie Island has thirty-three fresh water, man-made lagoons covering 40 acres (16 ha). In addition to providing irrigation water for the golf course, these same lagoons enhance the ecology of the island and the surrounding waters by reducing the rainwater run-off into the marsh and providing a source of food for alligators and fish-eating birds.

Callawassie has a long history of human occupation. Indians used the surrounding waters for shell fishing and portions of the adjacent land for cultivation. Approximately 275 years ago, Europeans began to significantly impact the ecology of the island primarily through logging most of the pine trees from the interior of the island and later by farming the land. There are a few relic pines, which are over 150 years old located near the south end of the island.[39]

The island has the following forest communities: inland maritime (live-oak hammock), subtropical magnolia, and three types of hardwood forests. These hardwood forests include lowland mixed hardwood, pine-mixed hardwood, and mixed-oak hardwood.[40]

The characteristic maritime-like forest occurring on the perimeter of Callawassie Island is composed of live oak and salt-tolerant species such as loblolly pine and palmetto. Because this plant community is influenced by wind and salt spray, it is considered an inland maritime forest or live oak hammock due to the presence of subtropical plants.[41]

Many large live oaks are scattered throughout the island, but it is believed that many were harvested for shipbuilding until the advent of ironclads during the Civil War, when wood was replaced by metal.[42]

The most unusual community on Callawassie Island is a subtropical magnolia forest characterized by the dominance of southern magnolia in the over story with white ash as a co-dominant. This is the only existing documented community of its type in South Carolina.[note 1] This magnolia community appears to be a virgin or near-virgin forest: an area exhibiting this amount of maturity requires several hundreds of years to reach its climax. One possible explanation for its existence is that it is situated on an Indian shell midden. Because this midden is composed of four feet of shell materials, the land was totally unsuitable for cultivation and appears to have been left undisturbed by early settlers as well as recent occupants of the island.[43]

The lowland mixed hardwood forest occurs in low-lying areas of the island in poorly drained soils.[44] A pine-mixed hardwood forest covers more acreage on the island than any other type and is generally the result of intermittent succession from areas used for agriculture or from the cutting of pine.[44] Finally, the oak-mixed hardwood forest, with the exception of the subtropical magnolia forest, is the most advanced succession stage on Callawassie Island.[45]

The natural habitat of the island and the waters that surround it support an abundant wildlife population with some of the most common species including: alligators, songbirds, birds of prey, water fowl, deer, fox, possum, raccoon, mink, otters, reptiles, amphibians and bottle-nosed dolphin.

Well established rookeries are found on two of the island's lagoons, where black-crowned night-herons, great egrets, and great blue herons nest and raise their young. Osprey and bald eagles also nest on the island; and although there is not a wood stork rookery on Callawassie Island, significant numbers of this formerly endangered species have made the island their home. Other bird species known to frequent the island include: doves (Zenaidura carolinensis), quail (Colinus virginianus), crows (Corvus sp.), and vultures (Carthes aura). Marshes provide a habitat for marine oriented species including terns, gulls, sandpipers ), loons and ibis.[2]

In developing the island, care has been taken to preserve as much of the natural habitat as possible. The Architectural Review Committee (ARC) has strict guidelines for the development and maintenance of landscape plans consistent with the long-term preservation of the island's natural environment. In addition, a land management plan provides guidelines and standards for the maintenance of the island's common properties and open spaces, including the golf course.

The Ecology Committee provides advice to the Callawassie Island Property Owners Association (CIPOA) Board regarding issues affecting the island's ecosystems and engages residents in environmental support activities significant to Callawassie Island.

Wildlife Habitat certification

In February 2006, Callawassie Island became the first community in South Carolina, and the fifteenth community in the United States, to achieve National Wildlife Federation (NWF) Community Wildlife Habitat certification. This status is awarded to communities whose vision is to develop a long-term plan of action and accompanying strategies that will ensure a continued sensitivity to the wildlife and natural environment the community presently supports and shelters.

Callawassie Islanders have accomplished this through resident involvement with the NWF Backyard Wildlife Habitat program and continuing wildlife education for all island residents. To date, more than 200 Callawassie properties have been certified as Backyard Wildlife Habitats, making Callawassie Island the largest per capita community Backyard Wildlife Habitat Community in America. Residents ensure wildlife habitat on their own properties provides the four basic wildlife needs: food, water, cover, and a place to raise their young.

Community Wildlife Habitat re-certification occurs annually by meeting specific criteria (judged by a point system) as set by NWF. While only forty points are required to maintain CWH certification, Callawassie typically earns more than 100 points each year. Reports are filed annually with NWF, providing a recount of programs that support the island's Community Wildlife Habitat Program.

Ecology and wildlife programs

In the past, Callawassie Island has either led or participated in and reported on the following ecology programs:

- A Community Ecology Guide: This publication is provided to all new residents via the community website (callawassieisland.org) and addresses the uniqueness of Callawassie Island from an ecological point of view.

- A Wildlife Habitat Preservation Program: Common community properties that are conducive for sustaining wildlife are identified and maintained.

- Educational Speaker/Dinner Programs: All programs have stewardship as their main theme and are scheduled as least quarterly throughout the year. Speakers include naturalists, biologists, and other representatives from various government-supported nature programs.

- Save-A-Snake Program: Through resident education, Callawassie residents are encouraged not to kill any snake they may encounter. Instead, the island promotes its snake relocation effort. Residents may call the island's herpetologist to have a snake removed from their property while he explains the benefits snakes have to the overall ecology of the island. Callawassie promotes the following slogan: "A Live Snake is a Good Snake."

- Chinese Tallow Tree Eradication Program: The goal is to prevent invasion and growth of Chinese Tallow trees, a non-native invasive species brought to the Southeast during Colonial times. Community volunteers inventory new growth and eradicate saplings, as needed.

- Annual River/Marsh Cleanup Program: Resident volunteers collect debris and trash that has been brought in by the tides from Callawassie's shoreline.

- SCORE-SC South Carolina Oyster Reef Restoration Enhancement: Volunteer residents have planned, implemented, and tracked development of the establishment of an oyster reef near the Sugar Mill Community Dock. On October 29, 2004, President George W. Bush recognized Callawassie Island for its commitment to the SCORE program.

- Bluebird Nest Monitoring Program: Resident volunteers maintain and monitor 60 bluebird houses located on out-of-play areas of the community's three golf courses during bluebird nesting season (March–August). Over 200 bluebirds fledge annually with statistics reported to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- Audubon Society Annual Christmas Bird Count: Each year resident volunteers spend a day in December counting species and the number of individual birds on Callawassie Island. A typical CBC produces over 80 species and almost 2000 individual birds. It is not unusual to spot a pair of bald eagles during the Christmas Bird Count. Callawassie Island has been home to nesting eagles for many years.

- Magnolia, Sequoia and Sugar Mill Parks: The Callawassie Island Garden Club maintains three walk-through parks, which have been designated as habitats and left in their natural state. All three parks border on the Okatie River and tidal creeks. Magnolia Park is unique in that it encompasses a sub-tropical magnolia forest (Magnolia grandiflora). The Magnolia grandiflora is native to the Southeastern United States, and the Magnolia Park on Callawassie Island is the only such forested site in South Carolina.[46]

- Annual Callawassie Island Ecology Calendar: This calendar celebrates the nature of the Lowcountry through the photographs of the island's photographers. Funds from the sale of the calendars help to support ecology projects throughout the island.

Gardens and parks

Callawassie Island has three parks, Magnolia, Sequoia, and Sugar Mill, as well as a butterfly garden for the enjoyment of its residents and visitors. A walk through each park provides the visitor with a different experience because of the distinctive flora and views of the tidal rivers and salt marshes that surround the island. Additionally, each park represents a different aspect of Callawassie's long and rich history. The community is committed to preserving the parks as nature preserves; its Master Plan states that only vegetation native to Callawassie Island can be planted in these parks. Because parks provide food, water, and shelter for wildlife, Sequoia Park and Magnolia Park have been designated as Backyard Wildlife Habitats by the National Wildlife Federation.[47] The parks and butterfly garden are maintained jointly by the Callawassie Island Property Owners Association and the Callawassie Garden Club.

Sugar Mill Park

Sugar Mill Park sits on a low bluff on the northwestern side of Callawassie Island, overlooking the salt marsh and a branch of the Chechessee River. A path flanked by live oaks draped with Spanish moss runs from Sugar Mill Drive to a community dock that provides access to the river. Native plants in the park include southern magnolias, yaupon hollies, wax myrtles, dwarf palmettos, and sabal palms. At the rear of the park near the bluff, are the tabby ruins of an early 19th-century sugar processing facility, the Callawassie Sugar Works.[48]

Magnolia Park

Magnolia Park is a one-acre subtropical magnolia forest located on the west side of Wild Magnolia Court. It is a near-virgin forest that has been left undisturbed for several hundred years and the only existing documented forest of its type in South Carolina. A path winds through the park to the edge of the tidal salt marsh with a view of a branch of the Colleton River. As its name suggests, the park is characterized by the dominance of southern magnolias that, along with white ash trees, create a dense canopy. This is also the site of an Indian shell midden, a mound of mollusk shells left behind by the early native inhabitants of Callawassie Island. Numerous sabal palms and dwarf palmettos create a lush tropical understory throughout the shady park.[49]

Sequoia Park

Sequoia Park is a one-acre pine forest on the southwest corner of Winding Oak Drive and Sequoia Court. A horseshoe-shaped path through a large stand of loblolly pines leads to an expansive view of the tidal salt marsh. This is a young forest resulting from the clearing of hardwood trees, either for their wood or for the cultivation of crops such as indigo or sea island cotton. Because of the tall pine canopy, sunlight is able to penetrate to encourage the growth of understory flora such as oaks, sweet gum trees, hickories, sassafras, yaupon hollies, and wax myrtles.

Butterfly Garden

Callawassie's butterfly garden, on the southeast corner of Callawassie Drive and South Oak Forest Drive, was expanded and replanted in 2010. It provides a colorful floral display from spring through late fall. The 6500-square-foot garden contains a variety of host and nectar plants to support butterflies throughout their life cycle. Caterpillars feed on host plants such as milkweed, parsley, butterfly weed, and snapdragons. Nectar plants in the garden include butterfly bushes, shasta daisies, zinnias, Joe Pye weed, yarrows, lantanas, sages, abelias, bee balm, and a vitex tree. Other plantings provide color to attract butterflies. Frequent visitors to the garden include monarch, swallowtail, little sulphur, cloudless sulphur, and tiger swallowtail butterflies. In 2011, the garden was certified by the North American Butterfly Association as a garden "that provides resources to increase the world's population of butterflies."

Amenities

In addition to the 27-hole golf course designed by Tom Fazio, voted Best Golf Course of Bluffton for 2011 by readers of Bluffton Today and the amenities mentioned above there is a golf practice facility and pro shop, a fitness senter, a tennis pro shop, a bocce/croquet court and the Callawassie Island and River Club Clubhouses.

Neighboring communities

Neighbouring communities include: Spring Island, Chechessee, Chechessee Bluff, and Heyward Point.

Notes

- There is only one other documented site of this community type in South Carolina located at Victoria Bluff, not far from Callawassie Island, which was destroyed in preparation for an industrial site (S.C. Wildlife and Marine Resources Department, Heritage Trust Programs Records, Columbia, S. C.).

References

- "About Beaufort County, SC". bcgov.net. 9 February 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Michie, James L., "An Archeological Investigation of the Cultural Resources of Callawassie Island, Beaufort County, South Carolina" (1982). Research Manuscript Series. Book 168. http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/archanth_books/168

- http://www.bcgov.net/departments/Administrative/beaufort-county-council/comprehensive-plan/2010-comprehensive-plan.php (2010-2-2.1)

- Brooks, Mark J. "Preliminary Archeological Investigations at the Callawassie Island Burial Mound (38BU19). Beaufort County, South Carolina" (1982). Research Manuscript Series. Book 177. http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/archanth_books/177

- Library of Congress (USA), Historic American Buildings Survey, Callawassie Sugar Works

- Mashaun, Simon, Sugar Mill's History Revealed, The Island Packet, July 8, 2002

- http://www.nwf.org/community. Action report: October/November 2006

- "List of Community Habitats". nwf.org. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "Island History". Callawassie Island. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- Data Recovery Investigations in the Marsh Lots of the Callawassie Burial Mound and Village Site (38BU19), Callawassie Island, Beaufort County, South Carolina . Bobby G. Southerlin, Dawn Reid, Christopher T. Espenshade, Thomas W. Neumann, Gary Crites. Brockington and Associates, Inc. 1998 (tDAR ID: 391048) ; doi:10.6067/XCV81G0N48

- University of South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, Columbia, South Carolina, July 1991

- Behan, William A., A Short History of Callawassie Island, South Carolina. The Lives & Times of Its Owners & Residents 1711-1985, iUniverse, Inc, 2004. book jacket.

- Data Recovery Investigations in the Marsh Lots of the Callawassie Burial Mound and Village Site (38BU19), Callawassie Island, Beaufort County, South Carolina . Bobby G. Southerlin, Dawn Reid, Christopher T. Espenshade, Thomas W. Neumann, Gary Crites. Brockington and Associates, Inc. 1998 (tDAR ID: 391048) ; doi:10.6067/XCV81G0N48

- Bense, Judy. Archeology of the Southeastern United States. Archeology of the Southeastern United States. Academic Press, SanDiego, California, 1974

- Rowland, Lawrence S. The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina, 1514-1861. University of South Carolina Press, 1998.

- Walter, Edgar. South Carolina: A History. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998.

- Behan, William A., A Short History of Callawassie Island, South Carolina. The Lives & Times of Its Owners & Residents 1711-1985, iUniverse, Inc. 2004 p.1.

- The Civil War in South Carolina: Selections from The South Carolina Historical Magazine. edited by Lawrence S. Rowland and Stephen G. Hoffius. Home Press. Charleston, South Carolina, p 3-18. The Secession Convention, "A Night of Bonfires and Music".

- Browning, Robert M. Jr. Success Is All That Was Expected: The South Atlantic Blockading Squadron During the Civil War. Brassey's Inc. 2002.

- The Civil War in South Carolina: Selections from The South Carolina Historical Magazine. edited by Lawrence S. Rowland and Stephen G. Hoffius. Home House Press. Charleston, South Carolina, p. 113-140. The Occupation Of The Sea Islands, "Laura M. Townsend and The Freed People of South Carolina", 1862-1901 by Kurt J. Wolf.

- United States Census; Agriculture, Industry, Social Statistics and Mortality Schedules for South Carolina 1850-1880; Helen Craig Carson and R. Nicholas Olsberg. Columbia, South Carolina, Department of Archives and History, 1971.

- Marscher, William. The Great Sea Island Storm of 1893. Macon: Mercer University Press 2004

- Gibson, Christine, "Our 10 Greatest Natural Disasters" American Heritage Aug./Sept. 2006, Vol.57 Issue 4.

- Behan, William A., A Short History of Callawassie Island, South Carolina. The Lives & Times of Its Owners & Residents 1711-1985, iUniverse 2004, p.134.

- Brooker, Colin H. "Callawassie Island Sugar Works: A Tabby Building Complex." In Michael Trinkley, editor, Further Investigations of Prehistoric Lifeways on Callawassie and Spring Islands, Beaufort County, S. C. Chicora Research Series 23. Chicora Foundation, 1991.

- Brooker, Colin H. 1991

- Tinkler, Robert. James Hamilton of South Carolina. Southern Biography Series. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004.

- Busick, Sean R. "James Hamilton, Jr." In Walter B. Edgar, ed., The South Carolina Encyclopedia.. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2006.

- Spalding, Thomas. Observations on the Method of Planting and Cultivating the Sugar-Cane in Georgia and South Carolina, published by Agricultural Society of South Carolina (Charleston) in 1816.

- National Park Service. Historic American Buildings Survey: Written Historical and Descriptive Data (addendum to: Callawassie Sugar Works HABS No. SC-857)

- Brooker, Colin H. "Written Historical and Descriptive Data," 2003, Addendum to Callawassie Sugar Works (HABS No. SC-857, 1983), Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U. S. Department of the Interior. Washington, D. C.: Historic American Buildings Survey, 2003. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/sc/sc1100/sc1115/data/sc1115data.pdf%5B%5D.

- "National Register Information System" National Register of Historic Places. National Park Services

- Aulbach-Smith, Cynthia A., The Vascular Flora of Callawassie Island, Beaufort County, South Carolina Department of Biology, University of South Carolina, 1982 p.1

- Aulbach-Smith, Cynthia A.,

- Phinney, Derrick M., Surveyor, Clemson Cooperative Extension, Forestry and Natural Resources Agent, survey August/September 2013

- Aulbach-Smith, Cynthia A., The Vascular Flora of Callawassie Island, Beaufort County, South Carolina, Department of Biology, University of South Carolina, 1982 p.7

- Aulbach-Smith, Cynthia A., p.8

- Bagwell, William, Director of Agronomy, Callawassie Island, International Society of Arboriculture Certified Arborist

- Aulbach-Smith, Cynthia A., p. 1

- Aulbach-Smith, Cynthia A., The Vascular Flora of Callawassie Island, Beaufort County, South Carolina, Department of Biology, University of South Carolina, 1982 p.9-11

- Aulbach-Smith, Cynthia A., e-mail Angela Estees (Callawassie Island Ecology Committee Board member) dated November 24, 2013

- Aulbach-Smith, Cynthia A., p. 2

- Aulbach-Smith, Cynthia A., The Vascular flora of Callawassie Island, Beaufort County, South Carolina, Department of Biology, University of South Carolina. 1982 pp.11, 17

- Aulbach-Smith, Cynthia A. p. 9

- Aulbach-Smith, Cynthia A. p. 10

- Aulbrach-Smith, Cynthia A.

- http://www.nwf.org/backyardwildlife

- The Historic American Buildings Survey, http://www.lcweb2.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/sc/sc1o100/sc1115/data/sc1115data.pdf%5B%5D.

- Aulbrach-Smith, Cynthia A., The Vascular Flora of Callawassie Island, Beaufort County, South Carolina, Department of Biology, University of South Carolina, 1982