California Eagle

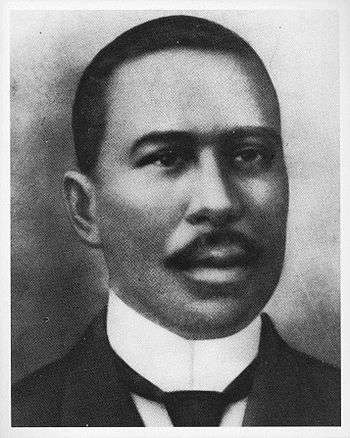

The California Eagle (1879–1964) was an African-American newspaper in Los Angeles, California. It was founded as The Owl in 1879 by John J. Neimore.[1]

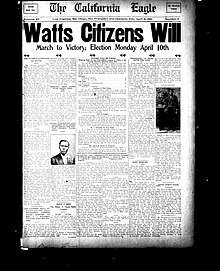

Front page from 1916 | |

| Type | Weekly newspaper |

|---|---|

| Founder(s) | John J. Neimore |

| Founded | 1879 |

| Ceased publication | January 7, 1964 |

| City | Los Angeles, California |

| Country | United States |

| OCLC number | 9188894 |

| Free online archives | archive |

| |

Charlotta Bass became owner in of the paper after Neimore's death in 1912. She owned and operated the paper, renamed the California Eagle, until 1951. Her husband, J. B. Bass, served as editor until his death in 1934. In the 1920s, they increased circulation to 60,000. During this period, Bass was also active as a civil rights campaigner in Los Angeles, working to end segregation in jobs, housing and transportation.

The newspaper was next owned for more than a decade by Loren Miller, who had been city editor. He also worked as a civil liberties lawyer and was a leader in the community. After he sold the paper in 1964 to accept an appointment as a judge of the Superior Court of the State of California [i.e., the trial courts] for Los Angeles County, the publication quickly lost ground, and closed that year.[2]

History

Neimore, a staunch Republican founded the newspaper as The Owl in 1879 to serve new arrivals to Los Angeles during the Great Migration, when millions of African-Americans left the Deep South. The paper offered information on employment and housing opportunities as well as news stories geared towards the newly arrived migrant population.[1] After Neimore's death in 1912, Charlotta Bass bought the paper and renamed it California Eagle.[3] She retired in 1951. Her husband, J.B. Bass, was editor until his death in 1934.[4]

By 1925, the newspaper had a circulation of 60,000, the largest of any African-American newspaper in California. Its publishers and editors were active in civil rights, beginning with campaigns for equitable hiring, patronage of black businesses, and an end to segregated facilities and housing.

In 1951 Bass sold the California Eagle to Loren Miller, the former city editor.[5] Miller was a Washburn University, Kansas law graduate. After he relocated to Los Angeles in 1930, he began writing for the Eagle and eventually became city editor. In 1945, Miller represented Hattie McDaniel and won her case against the "Sugar Hill" restrictive covenant case.[6] He was appointed in 1963 as a judge of the Superior Court [i.e., the trial courts] for Los Angeles County by Governor Edmund "Pat" Brown.[7] In 1963, Miller sold the paper to fourteen local investors in order to accept his appointment as judge. The California Eagle initially increased circulation from 3,000 to 21,000.[8] But within six months the paper had to close; on January 7, 1964, the California Eagle ceased publication after 85 years.

Platform

The California Eagle had the following platform:

- hiring of Negroes as a matter of right, rather than as a concession, in those institutions where their patronage creates a demand for labor;

- increased participation of Negroes in municipal, state, and national government;

- the abolition of enforced segregation and all other artificial barriers to the recognition of true merit;

- patronizing of Negroes by Negroes as a matter of principle;

- more rapid development of those communities in which Negroes live, by cooperation between citizens and those who have business investments in such communities; and

- enthusiastic support for a greater degree of service at the hands of all social, civic, charitable, and religious institutions

Staff

Below is a partial list of employees and contributors at The California Eagle in 1957:

- Francis Philip Waller Jr., advertising and circulation

- Abie Robinson, city reporting and general news

- Roy Smith, sports reporting

- Calme Russ, office management

- Maggie Hathaway, society reporting and civic/church matters

- Anthony Funches, copy boy, cleaning, circulation/distribution

The offices were located at 4071-4075 South Central Avenue.[9]

Notable people

Several newspaper employees went on to become prominent figures in their own right.

- T.R.M. Howard: From 1933 to 1935, Howard, then a medical student at Loma Linda University, was the circulation manager. He wrote a regular column entitled "The Negro in the Light of History" (later changed to "Our Fight"). After medical school Howard returned to Mississippi where he became a doctor. By the 1940s and 1950s, he had become one of the wealthiest and most influential blacks in the state and was a leading civil rights leader. He was later a mentor of Medgar Evers and Fannie Lou Hamer. He played a key role in finding evidence and witnesses in the Emmett Till murder case.[10]

- Robert C. Farrell (born 1936): journalist and member of the Los Angeles City Council, 1974–91

- Vera Jackson, (1912-1999), freelance and later staff photographer.[11]

Footnotes

- "John J. Neimore, founder and editor of the California Eagle, circa 1901/1910, Los Angeles". USC Digital Archive.

- Hoffman, Claire Giannini (April 2007). California, Past, Present, Future. California Almanac Co., Original from the University of California.

- "The California Eagle". PBS. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

- Charlotta Bass: Her Story Archived 2010-11-28 at the Wayback Machine, Charlotta Bass and the California Eagle, Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research, accessed 13 March 2011

- Sides, Josh (2003). L.A. City Limits: African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the Present. p. 20.

- Watts, Jill (2005). Hattie McDaniel: Black Ambition, White Hollywood. New York, NY: HarperCollins. p. 328. ISBN 0-06-051490-6.

- "California Eagle History: Charlotta Bass and the California Eagle". Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research. Archived from the original on March 10, 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- "California Eagle Photograph Collection". Archived from the original on August 19, 2009.

- Laura Pulido; Laura Barraclough; Wendy Cheng (24 March 2012). A People's Guide to Los Angeles. University of California Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-520-95334-5. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- David T. Beito and Linda Royster Beito, Black Maverick: T.R.M. Howard's Fight for Civil Rights and Economic Power (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), pp. 25-38.

- Moutoussamy-Ashe, Jeanne (1993). Viewfinders: black women photographers. Writers & Readers Publ. p. 86–87. ISBN 0863161588. OCLC 248680578.

Further reading

- Douglas Flamming, Bound for Freedom: Black Los Angeles in Jim Crow America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

- Josh Sides, L.A. City Limits: African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the Present. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

- B. Gordon Wheeler, Black California: The History of African-Americans in the Golden State. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1993.

- Scott Kurashige, The Shifting Grounds of Race: Black and Japanese Americans in the Making of a Multiethnic Los Angeles. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008.