Cakewalk

The cakewalk or cake walk was a dance developed from the "prize walks" held in the mid-19th century, generally at get-togethers on black slave plantations before and after emancipation in the Southern United States. Alternative names for the original form of the dance were "chalkline-walk", and the "walk-around". At the conclusion of a performance of the original form of the dance in an exhibit at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, an enormous cake was awarded to the winning couple. Thereafter it was performed in minstrel shows, exclusively by men until the 1890s. The inclusion of women in the cast "made possible all sorts of improvisations in the Walk, and the original was soon changed into a grotesque dance" which became very popular across the country.[3]

| Cakewalk | |

|---|---|

Five African American dancers perform a cakewalk, 1903 | |

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Southern United States |

| Typical instruments | |

| Derivative forms | Ragtime |

The fluid and graceful steps of the dance may have given rise to the colloquialism that something accomplished with ease is a 'cakewalk'.[4]

As a plantation dance

Early influences

The cakewalk was influenced by the ring shout, which survived from the 18th into the 20th century.[5]

First-person accounts

.jpg)

In the 1981 article "The Cakewalk: A Study in Stereotype and Reality", Brooke Baldwin cites "an almost exhaustive compilation of those accounts which have been found so far" with representations in the white press as early as 1863.[6] This compilation consists of eyewitness accounts by emancipated slaves from Virginia and Georgia recorded by WPA researchers in the 1930s, along with secondhand accounts from other sources. Baldwin notes that "when the researchers of the Federal Writer's Project of the WPA interviewed aged ex-slaves in the 1930s, there was no longer any need to suppress information about the happier moments of slave life"[7] such as when slaves had been able to covertly mock their owners without getting punished, through the signals and expression of dance.

Louise Jones: "de music, de fiddles an' de banjos, de Jews harp, an' all dem other things. Sech dancin' you never seen before. Slaves would set de flo' in turns, an' do de cakewalk mos' all night."[7]

Georgia Baker said that she sang a song when she was a child: "Walk light, ladies, De cake's all dough." She laughed and added, "Us didn't know it when we was singin' dat tune to us chillun dat when us growed up us would be cakewalkin' to de same song."[8]

Estella Jones said: "Cakewalkin' was a lot of fun durin' slavery time. Dey swep yards real clean and set benches for de party. Banjos wuz used for music makin'. De women's wor long, ruffled dresses wid hoops in 'em and de mens had on high hats, long split-tailed coats, and some of em used walkin' sticks. De couple dat danced best got a prize. Sometimes de slave owners come to dese parties 'cause dey enjoyed watchin' de dance, and dey 'cided who danced de best. Most parties durin' slavery time, wuz give on Saturday night durin' work sessions, but durin' winter dey wuz give on most any night."[9]

Secondhand, oral-tradition accounts

A South Carolinian told of Griffin, a fiddler who played for the dances of the whites as well as for the "annual cakewalks of his own people".[9] In 1960, a story told to him by his childhood nanny in 1901 was repeated by 80-year-old actor Leigh Whipple: "Us slaves watched white folks' parties where the guests danced a minuet and then paraded in a grand march, with the ladies and gentlemen going different ways and then meeting again, arm in arm, and marching down the center together. Then we'd do it too, but we used to mock 'em every step. Sometimes the white folks noticed it, but they seemed to like it; I guess they thought we couldn't dance any better."[9]

Ex-ragtime entertainer Shepard Edmonds recounted, in 1950, memories related to him by his parents from Tennessee: "...the cake walk was originally a plantation dance, just a happy movement they did to the banjo music because they couldn't stand still. It was generally on Sundays, when there was little work, that the slaves both young and old would dress up in hand-me-down finery to do a high-kicking, prancing walk-around. They did a take-off on the manners of the white folks in the 'big house', but their masters, who gathered around to watch the fun, missed the point. It's supposed to be that the custom of a prize started with the master giving a cake to the couple that did the proudest movement."[9] Baldwin concludes that the cakewalk was meant "to satirize the competing culture of supposedly 'superior' whites. Slaveholders were able to dismiss its threat in their own minds by considering it as a simple performance which existed for their own pleasure".[10]

Tom Fletcher, who was born in 1873 and had a show business career beginning in 1888,[11] wrote in 1954 that when he was a child, his grandparents told him about the chalk-line walk/cakewalk, but they did not know when it started.[12] Fletcher's grandfather told him, "your grandmother and I, we won all the prizes and were taken from plantation to plantation. The dance became a great fad. It took skill and good nerves...The plantation is where shows like yours first started, son."[13] Fletcher adds that the dance was called the "chalk like walk" and "There was no prancing, just a straight walk on a path made by turns and so forth, along which the dancers made their way with a pail of water on their heads. The couple that was the most erect and spilled the least water or no water at all was the winner."[14] He describes it being "revived with fancy steps by Charlie Johnson, a clever eccentric dancer" and becoming known as the "Cake Walk".[15][16]

"Cakewalk King" Charles E. Johnson related his grandmother's recollections of a dance-walk from "the old days". White guests would arrive by carriage to watch their slaves pair off and perform a dance-walk that was "as elegant and poised as a Mozart minuet", but flavored with "an exaggerated grace that was sometimes comical". Johnson relates that "The cadenced walking and high stepping was usually supplied by a violin, a drum and a horn of some kind. A towering, extra sweet coconut cake was the prize for the winning couple. The cakewalk was still popular at the dances of ordinary folks after the Civil War."[17]

Alternative explanations

Ethel L. Urlin, writing in the book Dancing, Ancient and Modern (1912), stated that the cakewalk "originated in Florida, where it is said that the Negroes borrowed the idea of it from the war dances of the Seminole...The negroes were present as spectators at these dances, which consisted of wild and hilarious jumping and gyrating, alternating with slow processions in which the dancers walked solemnly in couples. The idea grew, and style in walking came to be practised among the negroes as an art."[18]

The Encyclopedia of Social Dance echoed the Seminole Indian connection, stating that "Classes sprang up among the negroes for the teaching of the dance and the proper way to promenade" in the 1880s. As Florida developed into a winter resort, the dance became more performance oriented, and spread to Georgia, the Carolinas, Virginia, and finally New York.[19]

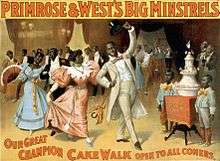

Street Swing's history of the Cakewalk describes it as "the first American dance to cross over from black to white society." After being danced in Minstrel shows, the Cakewalk became a ballroom dance among the upper classes.[20]

The authors of Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance reported that an early 1950s experiment with African guests turned up "no worthy African counterpart" to the Cakewalk.[21]

Cakewalk in minstrelsy, musicals, and as a popular dance

Amiri Baraka in Blues People explained the strangeness of a slave dance covertly mocking white slaveholders that later was adopted by whites unaware of the mockery: "If the cakewalk is a Negro dance caricaturing certain white customs, what is that dance, when, say, a white theater company attempts to satirize it as a Negro dance? I find the idea of white minstrels in blackface satirizing a dance satirizing a dance satirizing themselves a remarkable kind of irony--which, I suppose, is the whole point of minstrel shows."[22]

An exhibit at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial featured blacks singing folk songs and doing an old dance called the "chalk-line walk" in a plantation-like setting.[23] The dance was "done in the original fashion", as described by Fletcher.[3]

In 1877, performer-showmen Harrigan and Hart produced "Walking for Dat Cake, An Exquisite Picture of Negro Life and Customs" as a feature sketch at New York's Theater Comique on lower Broadway.[24] Thereafter it was performed in minstrel shows, exclusively by men until the 1890s.[3] In the 1893 production of The Creole Show, which had opened in 1889,[25] Dora Dean[26] and her husband Charles E. Johnson made a hit dancing the cakewalk, their specialty, as partners.[27] During its run from 1889 through 1897, this show played to crowds in Boston and New York at the old Standard Theatre on Greeley Square, one of the first productions to discard blackface makeup. The production had a Negro cast with a chorus line of sixteen girls, and at a time when women on stage, and partner dancing on stage were something new.[28] The inclusion of women in the cast "made possible all sorts of improvisations in the Walk, and the original was soon changed into a grotesque dance" which became very popular across the country.[3]

A Grand Cakewalk was held in Madison Square Garden, the largest commercial venue in New York City, on February 17, 1892.[29]

The Illustrated London News carried a report of a barn dance in Ashtabula, Ohio, in 1897 and written by an English woman traveler. "The origin of that expression 'taking the cake', had previously been an enigma to me, if I had ever thought about it before, but it was suddenly in an unexpected and most practical way (revealed to me)." Just before the ball was declared finished a long procession of couples was formed who walked in their very best manner around the room three times before the criticizing eyes of a dozen old people, who selected the best turned-out pair, and gravely presented them with a large plum cake.[30]

In July 1898, the musical comedy Clorindy, or The Origin of the Cake Walk opened on Broadway in New York. Will Marion Cook wrote ragtime music for the show. Black dancers mingled with white cast members for the first instance of integration on stage in New York.[31][32] Cook wrote, "My chorus sang like Russians, dancing meanwhile like Negroes, and cakewalking like angels, black angels! When the last note was sounded, the audience stood and cheered for at least ten minutes. This was the finale which Witmark had said no one would listen to. It was pandemonium.... But did that audience take offense at my rags and lack of conducting polish? Not so you could notice it!"[33]

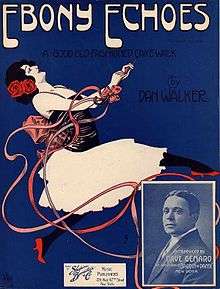

"Dusky troopers march & cake walk" was written by Will Hardy and published in 1900.[34][35]

Scott Joplin mentioned the cake walk in his folk ballet The Ragtime Dance, published in 1902.

Let me see you do the rag-time dance,

Turn left and do the cakewalk prance,

Turn the other way and do the slow drag -

Now take you lady to the World's Fair

And do the rag-time dance.

The French music hall singer and dancer Eugénie Fougère was filmed in 1899 in the rag-time cake-walk "Hello, Ma Baby," with which she made a sensation at the New York Theatre. She is said to have introduced the dance in Paris (France) in 1900 in the Théâtre Marigny after she returned from a tour in the United States.[36] Performances of the "Cake Walk", including a "Comedy Cake Walk" were filmed by the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company in 1903. Prancing steps were the main steps shown in the "Cake Walk" segment, which featured two couples, and a solo dancer. All dancers were African-American.[37] 1903 was the same year that both the cakewalk and ragtime music arrived in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Leaning far forward or far backward is associated with defiance in Kongo. "We are palm trees, bent forward, bent back, but we never break." Another interpretations of these motions were "melting" to the beat, or protecting what is new (leaning forward) with the past (leaning back). The appearance of the cakewalk in Buenos Aires may have influenced early styles of tango.[38]

"Cakewalk King" Charles E. Johnson, who, with his wife Dora Jean, achieved fame cakewalking throughout the United States and Europe described his kind of dance as "simple, dignified and well-dressed".[39]

The Cake Walk was more fluid and imaginative than the established two-step, it was nevertheless a regularized form, more improvisational than its previous form, but highly formalized compared to later dances such as the Charleston, Black Bottom and Lindy Hop.[40]

Cakewalk as a musical form

Most cakewalk music is notated in 2/4 time signature with two alternate heavy beats per bar, giving it an oompah rhythm.[41] The music was adopted into the works of various composers, including Robert Russell Bennett, John Philip Sousa, Claude Debussy and Louis Moreau Gottschalk. Debussy wrote "Golliwogg's Cake-walk" as the final movement of his Children's Corner suite for piano (published 1908),[42] and The Little Nigar, subtitled A Cakewalk, for a piano method in 1909. The Cake Walk was an adapted and amended two-step, which had been spawned by the popularity of marches, most notably by John Philip Sousa.[43]

Cakewalk music incorporated polyrhythm,[17] syncopation, and the hambone rhythm into the regular march rhythm.[45][46] Schuller considers the syncopation of the hambone rhythm to be "an idiomatic corruption, a flattened-out mutation of what was once the true polyrhythmic character of African music".[47] However, the figure known as the hambone is one of the most basic duple-pulse rhythmic cells in sub-Saharan African music traditions. The "hambone rhythm" is found in the oldest known traditional music of the Ewe of Ghana, Togo, and Dahomey, to name just one ethnic group.[48] It is heard in traditional drumming music, from Mali to Mozambique, and from Senegal to South Africa. The rhythmic figure is also prominent in popular African dance genres such as afrobeat, highlife, and soukous. Although its duple-pulse structure is identical to common time in European-based meter, the pattern of attack-points of the hambone rhythm possess a true African polyrhythmic character, or more precisely, a cross-rhythmic character.[49]

Quotations

Born in 1871 James Weldon Johnson made observations of a cakewalk at a ball in his novel The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man.

However, it was at one of these balls that I first saw the cake-walk. There was a contest for a gold watch, to be awarded to the hotel head-waiter receiving the greatest number of votes. There was some dancing while the votes were being counted. Then the floor was cleared for the cake-walk. A half-dozen guests from some of the hotels took seats on the stage to act as judges, and twelve or fourteen couples began to walk for a sure enough, highly decorated cake, which was in plain evidence. The spectators crowded about the space reserved for the contestants and watched them with interest and excitement. The couples did not walk round in a circle, but in a square, with the men on the inside. The fine points to be considered were the bearing of the men, the precision with which they turned the corners, the grace of the women, and the ease with which they swung around the pivots. The men walked with stately and soldierly step, and the women with considerable grace. The judges arrived at their decision by a process of elimination. The music and the walk continued for some minutes; then both were stopped while the judges conferred; when the walk began again, several couples were left out. In this way the contest was finally narrowed down to three or four couples. Then the excitement became intense; there was much partisan cheering as one couple or another would execute a turn in extra elegant style. When the cake was finally awarded, the spectators were about evenly divided between those who cheered the winners and those who muttered about the unfairness of the judges. This was the cake-walk in its original form, and it is what the colored performers on the theatrical stage developed into the prancing movements now known all over the world, and which some Parisian critics pronounced the acme of poetic motion.

Modern times

The American English term "cakewalk" was used as early as 1863 to indicate something that is very easy or effortless, although this metaphor may refer to the carnival game of the same name in referring to the fact that the latter's winners obtain their prize by doing no more than walking around in a circle.[50] Though the dance itself could be physically demanding, it was generally considered a fun, recreational pastime, covertly mocking slaveholder dance parties. The phrase "takes the cake" also comes from this practice,[51][52] as could "piece of cake."[50]

One version of the cakewalk is sometimes taught, performed included in competitions within the Scottish-inspired Highland dance community, especially in the southern United States. [53]

A version of the cakewalk seen in vintage film clips from the early 1900s is kept alive in the Lindy hop community through performances by the Hot Shots and through cakewalk classes held in conjunction with Lindy Hop classes and workshops.

Judy Garland performs a cakewalk in the 1944 MGM musical Meet Me in St. Louis.

Notes

- Philip M. Peek, Kwesi Yankah, African Folklore: An Encyclopedia, 2003, p. 33. ISBN 0-203-49314-1.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-04-19. Retrieved 2014-01-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Fletcher 1984, p. 103.

- Gandhi, Lakshmi (December 23, 2013). "The Extraordinary Story Of Why A 'Cakewalk' Wasn't Always Easy". NPR. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- Baldwin 1981, p. 209.

- Baldwin 1981, p. 207.

- Baldwin 1981, pp. 207, 208.

- Baldwin 1981, p. 208.

- Baldwin, p. 211.

- Fletcher 1984, p. 5.

- Fletcher 1984, p. 108. Fletcher's mother was born on a plantation and grew up in Ohio (p. 5).

- Fletcher 1984, p. 19.

- Jacqui Malone, Steppin' on the Blues, University of Illinois Press, 1996, p. 19. ISBN 0-252-02211-4.

- Fletcher 1984, p. 41.

- Lynne Fauley Emery, Black Dance in the United States from 1619 to 1970, California: National Press Books, 1972, p. 207. ISBN 0-87484-203-4.

- "Cakewalk King", Ebony, February 1953. Vol. 8, p. 100.

- "page 13 text available at this url". Archive.org. Retrieved 2011-05-19.

- Albert and Josephine Butler, Encyclopedia of Social Dance, 1971 and 1975. Albert Butler Ballroom Dance Service. New York, NY, p. 309 in 1975 edition. no ISBN or other ID.

- Watson, Sonny. "Cakewalk - Chalk Line Walk". Street Swing. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- Stearns & Stearns 1994, pp. 11, 13.

- Jones 1999, p. 86.

- Baldwin 1981, p. 212.

- DON’T GIVE THE NAME A BAD PLACE, New World Records 80265 Types and Stereotypes in American Musical Theater 1870-1900. Richard M. Sudhalter."Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-20. Retrieved 2011-05-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Free to Dance Timeline @". Pbs.org. Retrieved 2011-05-19.

- "Don't you think you'd like to fondle me / words and music by Hughie Cannon". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved 2011-05-19.

- Bernard L. Peterson, A Century of Musicals in Black and White: An Encyclopedia of Musical Stage Works By, About, Or Involving African Americans, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1993. p. 92. ISBN 0-313-26657-3, ISBN 978-0-313-26657-7.

- Stearns & Stearns 1994, p. 118.

- Lynn Abbott, Doug Seroff, Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889-1895, University Press of Mississippi, 2002, pp. 205, 206. Retrieved 2011-05-19.

- Giles Oakley, The Devil's Music: A History of the Blues, Da Capo Press, 1997, p. 31. ISBN 0-306-80743-2, ISBN 978-0-306-80743-5.

- African American Dance

- "Black Broadway web site". Theatredance.com. Retrieved 2011-05-19.

- Will Marion Cook, "Clorindy, the Origin of the Cakewalk" (1944). Printed in Theatre Arts (September 1947), pp. 61–65. Excerpt via Homepage.mac.com, 2008-04-10. Retrieved 2011-05-19.

- "Dusky troopers march & cake walk (b0319) - Historic American Sheet Music - Duke Libraries". Library.duke.edu. 2010-03-16. Retrieved 2011-05-19.

- Sheet music covers for more cake walks can be viewed here:

- "Historic American Sheet Music". Library.duke.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-03-14. Retrieved 2011-05-19.

- See Le Journal, 20 January 1903 and Le Figaro, 13 February 1903.

- America Dances! 1897-1948, DanceTime Publications, 2003, segments of the same name. DVD.

- Robert Farris Thompson, Tango The Art History of Love, Pantheon Books, 2005, pp. 8, 89, 108. ISBN 0-375-40931-9.

- "Cakewalk King", Ebony, February 1953, p. 106.

- James Haskins with Kathleen Benson, Scott Joplin the Man Who Made Ragtime, Doubleday and Company, 1978, p. 74 ISBN 0-385-11155-X.

- The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz. Revised edition, 1987. Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. 14, 15.

- Crawford, Richard (2000). An Introduction to America's Music. New York City: W. W. Norton & Co.

- Stearns & Stearns 1994, p. 11.

- Orovio, Helio. 1981. Diccionario de la Música Cubana, Havana: Editorial Letras Cubanas, p. 237. ISBN 959-10-0048-0.

- Baldwin 1981, p. 210.

- "Cakewalks - Early Syncopation". Replay.web.archive.org. 2007-04-03. Archived from the original on April 3, 2007. Retrieved 2011-05-19.

- Schuller, Gunther (1968). Early Jazz - Its Roots and Musical Development, Oxford University Press, p. 15 ISBN 0-19-500097-8, ISBN 0-19-504043-0.

- "Sohu," Ritual Music of the Yeve, (Ladzekpo brothers). Makossa phonorecord 86011 (1982).

- Peñalosa, David (2009: 41). The Clave Matrix; Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Redway, CA: Bembe Inc. ISBN 1-886502-80-3.

- Harper, Douglas. "cakewalk". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- "Cakewalk Dance". Streetswing Dance History Archive. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- Elijah Wald, How the Beatles Destroyed Rock 'n' Roll: An Alternative History of American Popular Music, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 30. ISBN 978-0-19-534154-6.

- Kirsty Duncan PhD. "Introduction to Highland Dancing". Electric Scotland. Retrieved 2007-04-05.

References

- Baldwin, Brooke (1981). "The Cakewalk: A Study in Stereotype and Reality". Journal of Social History. Oxford University Press. 15 (2): 205–218. doi:10.1353/jsh/15.2.205. ISSN 0022-4529. JSTOR 3787107.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fletcher, Tom (1984) [1954]. One Hundred Years of the Negro in Show Business. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306762196. OL 10325447M.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stearns, Marshall Winslow; Stearns, Jean (1994) [1968]. Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance. With a foreword and afterword by Brenda Bufalino. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80553-7. LCCN 93040957.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, LeRoi (1999) [1963]. Blues People: Negro Music in White America. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-688-18474-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cake walk. |

| Look up cakewalk in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

%2C_by_William_H._Johnson.jpg)