Butchulla

The Butchulla, also written Butchella, Badjala, Badjula, Badjela, Bajellah, Badtjala and Budjilla are an Aboriginal Australian people of Fraser Island, Queensland, and a small area of the nearby mainland of southern Queensland.

THIS MONUMENT IS DEDICATED TO PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE MEMBERS OF ABORIGINAL TRIBES IN THE WIDE BAY AREA, IN PARTICULAR THE BUTCHELLA TRIBE.

THIS BRONZE PLAQUE DEPICTS A STORY TELLER RELATING STORIES OF THE DREAMTIME TO THE CHILDREN WHILE THE WOMAN IN THE SUN LOOKS ON.

Language

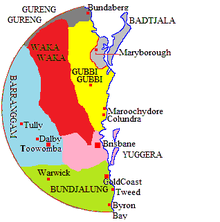

The Butchulla spoke Badjala, considered to have been a dialect of Gubbi Gubbi,[1] like other Fraser Island dialects.[2] Their ethnonym, variously transcribed as Butchulla, Batjala, Badjala and other variations, has been etymologised as signifying "sea folk", though Norman Tindale suggested that the word better lends itself to an analysis as combining ba ("no") with the suffix tjala, meaning "tongue".[3] In the 1800s there were reported to be 19 groups that lived on the island permanently, with the island split into three sections. The people in the northern part of the island (Ngulungbara) were a separate group from the other two and did not want to be associated with the Badjala people. The people of the lower part of the island (Dulingbara) also moved along the coast line to Noosa area, and their language was mixture of Badjala and Kabi-Kabi, as these people were reported being at the mission. Due to fighting with the new settlers and for their survival, in about 1902 the people of Fraser Island and surrounding area were taken to Yarrabah near Cairns and to Barambah station (Cherbourg).

The Batjala language is spoken in the Hervey Bay region inland towards Maryborough and Mt Bauple; as well as along the Fraser Coast, including Fraser Island.[4]

Country

Butchulla lands were concentrated in the centre of Thoorgine, or Fraser Island, and extended over 1,700 square miles (4,400 km2) to the coastal mainland (Cooloola[5]) south of Noosa.[3] The Butchulla route to the mainland ran through the lower waters of the Tinana Creek and their territory ran north to Pialba in Hervey Bay, and their borders to the west ran parallel to the upper Mary River.[3][6] To the southwest of their mainland territory were the Gubbi Gubbi,[6] with the territories of the Butchulla, Gubbi Gubbi and Dulingbara sometimes marked as meeting at Mount Bauple.[7] Some two decades after the arrival of Europeans, the original population of Fraser Island was estimated to be in the range of approximately 2,000 people, according to Archibald Meston,[8] a figure which, if true, would mean that the ecology was sufficiently rich in food resources to sustain one of the densest pre-contact populations of the Australian continent, paralleling only the Kaiadilt of Bentinck Island.[3]

Social organisation

Fraser island's abundance of fish resources made it rank, with the Kaiadilt homeland of Bentinck Island, as one of the two most densely populated areas on the Australian continent.[9]

The Fraser Island people were generally classified into three distinct units: Ngulungbara, Butchulla and Dulingbara, each composed of several clan groups, and, altogether, making up 19 subgroups.[10] The Ngulungbara were in the northern sector, the Butchulla in the strict sense occupied the middle of the island, while the Dulingbara lay south. The Dulingbara and Ngulungbara claimed a separate, distinct tribal status.[lower-alpha 2]

History of contact

Archaeological and radiocarbon studies of a lead weight containing fragments of Loisels pumice unearthed on the island identify the lead component as of French provenance, and the pumice suggests that the object may have arrived on the beach between 1410 and 1630 C.E., the first date prior to Ferdinand Magellan's circumnavigation of the world.[11]

Matthew Flinders was the first white to land on the island, at Bool Creek on Sandy Cape in July 1802 and made short contact with the Ngulungbara horde.[8] In 1836 survivors of the shipwreck of a brig, the Stirling Castle managed to make their way south and landed up on the island. Eliza Fraser, the late captain's wife, managed to survive among the local islanders for several weeks.

The island began to be occupied by whites in 1849. At that time, the Indigenous population of the 19 clans was estimated to be around 2,000. Within three decades (1879), their numbers had dropped to around 300-400, a collapse attributed by an informant of the then Chief Commissioner of Brisbane to shootings by the Australian native police, and the effects of venereal disease and alcohol introduced by whites.[12]

The main remnant of the Butchella people was transferred to Yarrabah sometime around 1902.[3]

Native title

In 2014 an Australian Federal Court granted Native title rights to Fraser Island to the Butchulla people.[13]

Alternative names

- Badjela

- Badtala

- Badyala

- Batyala (exonym used by the Wakawaka for the coastal Butchulla)

- Bidhala (Kabikabi exonym for coastal Butchulla)

- Butchulla

- Dulingbara

- Ngulungbara

- Patyala

- Thoorgine (native toponym for the island)

Source: Tindale 1974, p. 165

Some words

- baboon. (father)

- koorooman (kangaroo)

- muthare. (white man)

- nbong. (mother)

- watcher karome. (wild dog)

Source: Commissioner 1887, p. 148

Notes

- This map is indicative only.

- "New is the suggestion that the Dulingbara, either a separate tribe, a horde of the Kabikabi, or of the Batjala, claimed possession of the southern third of Fraser Island. The Batjala are thus credited as holding only the middle third of the island, but having extensions of their territory onto the mainland at Tinina (or Tinane) Creek with rights northward along the coastal strip to Pialba. From Gaiarbau and other sources it seems clear that the northern end of Fraser Island was held by the Ngulungbara which he regarded as a separate tribe, despite the -bara suffix of the name."(Tindale 1974, p. 125)

Citations

- Dixon 2002, p. xxxiv.

- Brown 2000, p. 26.

- Tindale 1974.

- SLQ-Butchulla.

- Brown 2000, p. 13.

- Brown 2000, p. 24.

- Brown 2000, p. 25.

- Williams 2002, p. 3.

- Tindale 1974, p. 165.

- Commissioner 1887, p. 144.

- Ward et al. 1999, p. 28.

- Commissioner 1887, pp. 144,146.

- Buchanan, Kay & Ford 2014.

Sources

- Brown, Elaine (2000). Cooloola Coast: Noosa to Fraser Island: the Aboriginal and Settlers Histories of a Unique Environment. University of Queensland Press. ISBN 978-0-702-23129-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buchanan, Kallee; Kay, Ross; Ford, Elaine (7 November 2014). "Fraser Island: Native title rights granted to Indigenous people by Federal Court". ABC News.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Butchulla language". State Library of Queensland. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Commissioner (1887). "Great Sandy, or Fraser's Island". In Curr, Edward Micklethwaite (ed.). The Australian race: its origin, languages, customs, place of landing in Australia and the routes by which it spread itself over the continent. Volume 3. Melbourne: J. Ferres. pp. 144–149.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dixon, Robert M. W. (2002). Australian Languages: Their Nature and Development. Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47378-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tindale, Norman (1974). Aboriginal Tribes of Australia, Batjala (QLD). Australian National University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ward, W. T.; Little, I. P.; Roberts, G. M.; Gulson, B. L.; O'Leary, B. M.; Price, D. M. (April 1999). "Ancient Lead Weight Found with Loisels Pumice near Hook Point, Fraser Island, Queensland". Archaeology in Oceania. 34 (1): 25–30. JSTOR 40387111.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Fred (2002) [First published 1983]. Princess K'Gari's Fraser Island: A History of Fraser Island. Jacaranda Press. ISBN 978-0-958-10340-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)