Burmester's theory

Burmester theory comprises geometric techniques for synthesis of linkages in the late 19th century.[1] It was introduced by Ludwig Burmester (1840–1927). His approach was to compute the geometric constraints of the linkage directly from the inventor's desired movement for a floating link. From this point of view a four-bar linkage is a floating link that has two points constrained to lie on two circles.

Burmester began with a set of locations, often called poses, for the floating link, which are viewed as snapshots of the constrained movement of this floating link in the device that is to be designed. The design of a crank for the linkage now becomes finding a point in the moving floating link that when viewed in each of these specified positions has a trajectory that lies on a circle. The dimension of the crank is the distance from the point in the floating link, called the circling point, to the center of the circle it travels on, called the center point.[2] Two cranks designed in this way form the desired four-bar linkage.

This formulation of the mathematical synthesis of a four-bar linkage and the solution to the resulting equations is known as Burmester Theory.[3][4][5] The approach has been generalized to the synthesis of spherical and spatial mechanisms.[6]

Finite position synthesis

Geometric formulation

Burmester theory seeks points in a moving body that have trajectories that lie on a circle called circling points. The designer approximates the desired movement with a finite number of task positions; and Burmester showed that circling points exist for as many as five task positions. Finding these circling points requires solving five quadratic equations in five unknowns, which he did using techniques in descriptive geometry. Burmester's graphical constructions still appear in machine theory textbooks to this day.

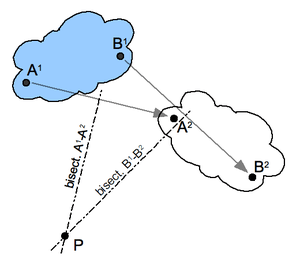

Two positions: As an example consider a task defined by two positions of the coupler link, as shown in the figure. Choose two points A and B in the body, so its two positions define the segments A1B1 and A2B2. It is easy to see that A is a circling point with a center that is on the perpendicular bisector of the segment A1A2. Similarly, B is a circling point with a center that is any point on the perpendicular bisector of B1B2. A four-bar linkage can be constructed from any point on the two perpendicular bisectors as the fixed pivots and A and B as the moving pivots. The point P is clearly special, because it is a hinge that allows pure rotational movement of A1B1 to A2B2. It is called the relative displacement pole.

Three positions: If the designer specifies three task positions, then points A and B in the moving body are circling points each with a unique center point. The center point for A is the center of the circle that passes through A1, A2 and A3 in the three positions. Similarly, the center point for B is the center of the circle that passes through B1, B2 and B3. Thus for three task positions, a four-bar linkage is obtained for every pair of points A and B chosen as moving pivots.

Four positions: Graphical solution to the synthesis problem becomes more interesting in the case of four task positions, because not every point in the body is a circling point. Four task positions yield six relative displacement poles, and Burmester selected four to form the opposite pole quadrilateral, which he then used to graphically generate the circling point curve (Kreispunktcurven). Burmester also showed that the circling point curve was a circular cubic curve in the moving body.

Five positions: To reach five task positions, Burmester intersects the circling point curve generated by the opposite pole quadrilateral for a set of four of the five task positions, with the circling point curve generated by the opposite pole quadrilateral for different set of four task positions. Five poses imply ten relative displacement poles, which yields four different opposite pole quadrilaterals each having its own circling point curve. Burmester shows that these curves will intersect in as many as four points, called the Burmester points, each of which will trace five points on a circle around a center point. Because two circling points define a four-bar linkage, these four points can yield as many as six four-bar linkages that guide the coupler link through the five specified task positions.

Algebraic formulation

Burmester's approach to the synthesis of a four-bar linkage can be formulated mathematically by introducing coordinate transformations [Ti] = [Ai, di], i = 1, ..., 5, where [A] is a 2×2 rotation matrix and d is a 2×1 translation vector, that define task positions of a moving frame M specified by the designer.[6]

The goal of the synthesis procedure is to compute the coordinates w = (wx, wy) of a moving pivot attached to the moving frame M and the coordinates of a fixed pivot G = (u, v) in the fixed frame F that have the property that w travels on a circle of radius R about G. The trajectory of w is defined by the five task positions, such that

Thus, the coordinates w and G must satisfy the five equations,

Eliminate the unknown radius R by subtracting the first equation from the rest to obtain the four quadratic equations in four unknowns,

These synthesis equations can be solved numerically to obtain the coordinates w = (wx, wy) and G = (u, v) that locate the fixed and moving pivots of a crank that can be used as part of a four-bar linkage. Burmester proved that there are at most four of these cranks, which can be combined to yield at most six four-bar linkages that guide the coupler through the five specified task positions.

It is useful to notice that the synthesis equations can be manipulated into the form,

which is the algebraic equivalent of the condition that the fixed pivot G lies on the perpendicular bisectors of each of the four segments Wi − W1, i = 2, ..., 5.

Input-output synthesis

One of the more common applications of a four-bar linkage appears as a rod that connects two levers, so that rotation of the first lever drives the rotation of the second lever. The levers are hinged to a ground frame and are called the input and output cranks, and the connecting rod is the called the coupler link. Burmester's approach to the design of a four-bar linkage can be used to locate the coupler so that five specified angles of the input crank result in five specified angles of the output crank.

Let θi, i = 1, ..., 5 be the angular positions of the input crank, and let ψi, i = 1, ..., 5 be the corresponding angles of the output crank. For convenience locate the fixed pivot of the input crank at the origin of the fixed frame, O = (0, 0), and let the fixed pivot of the output crank be located at C = (cx, cy), which is chosen by the designer. The unknowns in this synthesis problem are the coordinates g = (gx, gy) of the coupler attachment to the input crank and the coordinates w = (wx, wy) of the attachment to the output crank, measured in their respective reference frames.

While the coordinates of w and g are not known their trajectories in the fixed frame are given by,

where [A(•)] denotes the rotation by the given angle.

The coordinates of w and g must satisfy the five constraint equations,

Eliminate the unknown coupler length R by subtracting the first equation from the rest to obtain the four quadratic equations in four unknowns,

These synthesis equations can be solved numerically to obtain the coordinates w = (wx, wy) and g = (gx, gy) that locate the coupler of the four-bar linkage.

This formulation of the input-output synthesis of a four-bar linkage is an inversion of finite-position synthesis, where the movement of the output crank relative to the input crank is specified by the designer. From this viewpoint the ground link OC is a crank that satisfies the specified finite positions of the movement of the output crank relative to the input crank, and Burmester's results show that its existence guarantees the presence of at least one coupler link. Furthermore, Burmester's results show that there may be as many as three of these coupler links that provide the desired input-output relationship.[6]

References

- Hartenberg, R. S., and J. Denavit. Kinematic Synthesis of Linkages. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964. on-line through KMODDL.

- Burmester, L. Lehrbuch der Kinematik. Leipzig: Verlag von Arthur Felix, 1886.

- Suh, C. H., and Radcliffe, C. W. Kinematics and Mechanism Design. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1978.

- Sandor, G. N., and Erdman, A. G. Advanced Mechanism Design: Analysis and Synthesis. Vol. 2. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1984.

- Hunt, K. H. Kinematic Geometry of Mechanisms. Oxford Engineering Science Series, 1979.

- J. M. McCarthy and G. S. Soh. Geometric Design of Linkages. 2nd Edition, Springer, 2010.

Further reading

- Ian R. Porteous (2001) Geometric Differentiation, § 3.5 Burmester Points, page 58, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-00264-8 .

- M. Ceccarelli and T. Koetsier, Burmester and Allievi: A Theory and Its Application for Mechanism Design at the End of the 19th Century, ASME 2006

External links

- R. E. Kaufman provides links to videos of KINSYN which is the original interactive graphics software implementing Burmester's four position synthesis.

- The University of Minnesota Lincages software implements Burmester's four position synthesis.

- The Synthetica 3.0 software applies Burmester's approach to the synthesis of spatial linkages.

- Linkage synthesis on mechanicaldesign101.com provides a Mathematica notebook for Burmester's five position synthesis.