Buildings and architecture of New Orleans

The buildings and architecture of New Orleans are reflective of its history and multicultural heritage, from Creole cottages to historic mansions on St. Charles Avenue, from the balconies of the French Quarter to an Egyptian Revival U.S. Customs building and a rare example of a Moorish revival church.

The city has fine examples of almost every architectural style, from the baroque Cabildo to modernist skyscrapers.

Domestic architectural styles

Creole cottage

Creole cottages are scattered throughout the city of New Orleans, with most being built between 1790 and 1850. The majority of these cottages are found in the French Quarter, the surrounding areas of Faubourg Marigny, the Bywater, and Esplanade Ridge. Creole cottages are 1½-story, set at ground level. They have a steeply pitched roof, with a symmetrical four-opening façade wall and a wood or stucco exterior. They are usually set close to the property line.[1][2]

American townhouse

Many buildings in the American townhouse style were built from 1820 to 1850 and can be found in the Central Business District and Lower Garden District. American townhouses are narrow, three-story structures made of stucco or brick. An asymmetrical arrangement of the façade with a balcony on the second floor sits close to the property line.[3][4]

Creole townhouse

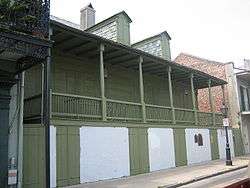

Creole townhouses are perhaps the most iconic pieces of architecture in the city of New Orleans, comprising a large portion of the French Quarter and the neighboring Faubourg Marigny. Creole townhouses were built after the Great New Orleans Fire (1788), until the mid-19th century. The prior wooden buildings were replaced with structures with courtyards, thick walls, arcades, and cast-iron balconies. The façade of the building sits on the property line, with an asymmetrical arrangement of arched openings. Creole townhouses have a steeply-pitched roof with parapets, side-gabled, with several roof dormers and strongly show their French and Spanish influence. The exterior is made of brick or stucco.[5][4]

Shotgun house

The shotgun house is a narrow domestic residence, usually no more than 12 feet (3.5 m) wide, with doors at each end. This style of architecture developed in New Orleans and is the city's predominant house type. The earliest extant New Orleans shotgun house, at 937 St. Andrews St., was built in 1848. Shotguns were built through the 1920s and can be found throughout the city.

Typically, shotgun houses are one-story, narrow rectangular homes raised on brick piers. Most have a narrow porch covered by a roof apron that is supported by columns and brackets, which are often ornamented with lacy Victorian motifs. Many variations of the shotgun house exist, including double shotguns (essentially a duplex); camel-back house, also called humpback, with a partial second floor on the end of the house; double-width shotgun, a single house twice the width of a normal shotgun; and "North shore" houses, with wide verandas on both sides, built north of Lake Pontchartrain in St. Tammany Parish.[6][7]

Double-gallery house

Double-gallery houses were built in New Orleans between 1820 and 1850. Double-gallery houses are two-story houses with a side-gabled or hipped roof. The house is set back from the property line, and it has a covered two-story gallery which is framed and supported by columns supporting the entablature.

The façade has an asymmetrical arrangement of its openings. These homes were built as a variation on the American townhouses built in the Garden District, Uptown, and Esplanade Ridge, areas which in the 19th century were thought of as suburbs.[3]

California-style bungalow house

California bungalow houses were built from the early-to-mid-20th century in neighborhoods such as Mid-City, Gentilly Terrace, Broadmoor, and scattered throughout older neighborhoods as in-fill. California bungalows are noted for their low-slung appearance, being more horizontal than vertical. The exterior is often wood siding, with a brick, stucco, or stone porch with flared columns and roof overhang. Bungalows are one or one-and-a-half-story houses, with sloping roofs and eaves showing unenclosed rafters. They typically feature a gable (or an attic vent designed to look like a gable) over the main portion of the house.

New Orleans neighborhoods

French Quarter

Due to refurbishings in the Victorian style after the Louisiana Purchase, only a handful of buildings in the French Quarter preserve their original colonial French or Spanish architectural styles, concentrated mainly around the cathedral and Chartres Street. Most of the 2,900 buildings in the Quarter are either of "second generation" Creole or Greek revival styles. Fires in 1788 and 1794 destroyed most of the original French colonial buildings, that is, "first generation" Creole. They were generally raised homes with wooden galleries, the only extant example being Madame John's Legacy at 632 Dumaine Street, built during the Spanish period in 1788. The Ursuline Convent (1745–1752) is the last intact example of French colonial architecture. Of the structures built during the French or Spanish colonial eras, only some 25 survive to this day (including the Cabildo and the Presbytère), in a mixture of colonial Spanish and neo-classical styles.

Following the two great fires of New Orleans in the late 18th century, Spanish administrators enforced strict building codes, requiring strong brick construction and thick fire proof walls between adjoining buildings to avoid another city fire and to resist hurricanes but the Spanish did not directly influence much of the Quarter's architecture. Spanish influence came indirectly in the form of Creole style, a mixture of French and Spanish architecture with some elements from the Caribbean.

Two-thirds of the French Quarter structures date from the first half of the 19th century, the most prolific decade being the 1820s, when the city was growing at an amazing rate. Records show that not a single Spanish architect was operating in the city by that time; only French and American were, the latter gradually replacing the former as Creole style was being replaced by Greek revival architecture in the 1830s and 1840s.

From its south end to the intersection with Claiborne Avenue, Canal Street is extremely dense with buildings. Each building, being no larger than half a New Orleans block, has a notably intricate façade. All of these buildings contrast each other in style, from Greek revival, Art Nouveau, and Art Deco, to Renaissance Colonial, and one of Gothic architecture. Also there is Post-modern, Mid-century modern, Streamline Moderne, and other types of 20th-century architecture. However, most of these buildings have lost their original interiors because of hurricane damage and business renovations.

Jackson Square took its current form in the 1850s: the Cathedral was redesigned, mansard rooftops were added to the Cabildo and to the Presbytère, and the Pontalba apartments were built on the sides of the square, adorned with ironwork balconies. The popularity of wrought iron or cast iron balconies in New Orleans began during this period.

St. Charles Avenue

St. Charles Avenue is famed for its large collection of Southern mansions in many styles of architecture, including Greek Revival, Colonial, and Victorian styles such as Italianate and Queen Anne.

The city of New Orleans was the largest in the Confederacy at the start of the American Civil War. The city was captured barely a year after the start of hostilities without military conflict in, or bombardment of, the city itself. As a result, New Orleans retains the largest collection of surviving antebellum architecture.

St. Charles Avenue is also home to Loyola University New Orleans and Tulane University, both campuses of which sit across the street from Audubon Park.

Central Business District

For much of its history, New Orleans' skyline consisted of only low- and mid-rise structures. The soft local soils are susceptible to subsidence, and there was doubt about the feasibility of constructing large high-rises in such an environment. The 1960s brought the trail-blazing World Trade Center and Plaza Tower, which demonstrated that high-rise could stand firm on the soft ground.

One Shell Square took its place as the city's tallest building in 1972, a title it still holds. The oil boom of the early 1980s redefined the New Orleans skyline again with the development of the Poydras Street corridor. Today, high-rises are clustered along Canal and Poydras Streets in the Central Business District (CBD).

Located within the CBD is one of the world's most famous pieces of postmodern architecture, Charles Willard Moore's Piazza d'Italia.

The district has a number of significant historicist buildings. Perhaps the most notable are the Moorish revival Immaculate Conception Church and the Egyptian revival U.S. Custom House.

Lafayette Square has some notable art deco civic buildings.

Cemeteries

New Orleans is known for its elaborate European-style cemeteries, including Greenwood Cemetery, Saint Louis Cemeteries, and Metairie Cemetery. Because of New Orleans' high water table, graves are not dug "six feet under": stone tombs were the norm. Many cemeteries in New Orleans have historical significance.

Preservation

Many organizations, notably the Friends of the Cabildo[8] and the Preservation Resource Center,[9] are devoted to promoting the preservation of historic neighborhoods and buildings in New Orleans. New Orleans has suffered from the same problems with sinking property values and urban decline as other major cities. Many historic structures have been threatened with demolition. During Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita, several historic New Orleans neighborhoods were flooded, and numerous historic buildings were severely damaged. However, there is a general notion by both rebuilders and new developers to preserve the architectural integrity of the city.

Notable structures

|

|

- U.S. Custom House, notable Egyptian revival building.

- Immaculate Conception Church, notable Moorish revival building.

See also

- American colonial architecture - includes French and Spanish colonial style

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Orleans Parish, Louisiana

- History of New Orleans

- List of tallest buildings in New Orleans

- List of streets of New Orleans

- Neighborhoods in New Orleans

- James H. Dakin

- James Gallier

- Benjamin Henry Latrobe

References

- Vogt, Lloyd (1985). New Orleans Houses: A House Watcher's Guide. Pelican Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 0-88289-299-1.

- Building Types and Architectural Styles. City of New Orleans Historic District Landmarks Commission. 2011. p. 03‐3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2014.

- Vogt, Lloyd (1985). New Orleans Houses: A House Watcher's Guide. Pelican Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 0-88289-299-1.

- Building Types and Architectural Styles. City of New Orleans Historic District Landmarks Commission. 2011. p. 03‐4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2014.

- Vogt, Lloyd (1985). New Orleans Houses: A House Watcher's Guide. Pelican Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 0-88289-299-1.

- Vogt, Lloyd (1985). New Orleans Houses: A House Watcher's Guide. Pelican Publishing. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0-88289-299-1.

- Building Types and Architectural Styles. City of New Orleans Historic District Landmarks Commission. 2011. p. 03‐6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2014.

- "Friends of the Cabildo and the New Orleans Architecture Series". New Orleans Preservation Timeline Project. Tulane University School of Architecture. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- "Preservation Resource Center and Preservation In Print". New Orleans Preservation Timeline Project. Tulane University School of Architecture. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

Further reading

Bruno, R. Stephanie (2011). New Orleans Streets: A Walker's Guide to Neighborhood Architecture. Pelican Publishing. ISBN 978-1589808744.

Campanella, Richard, Geographies of New Orleans : Urban Fabrics before the Storm, Gretna, LA, Pelican Publishing, 2006.

Kingsley, Karen. Buildings of Louisiana, New York: Society of Architectural Historians, 2003.

Lewis, Peirce. New Orleans: The Making of an Urban Landscape, 2nd ed., Santa Fe, NM: Center for American Places, 2003.

Toledano, Roulhac B. (2010). A Pattern Book of New Orleans Architecture. Pelican Publishing. ISBN 978-1589806948.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Buildings in New Orleans. |

- Vieux Carré Commission, City of New Orleans

- New Orleans Architecture

- Preservation Resource Center

- Southeastern Architectural Archive, Special Collections Division, Tulane University Libraries