Bombardment of Upolu

The Bombardment of Upolu, in 1841, was the second engagement with islanders of the Pacific Ocean during the United States Exploring Expedition.

| Bombardment of Upolu | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the United States Exploring Expedition | |||||||

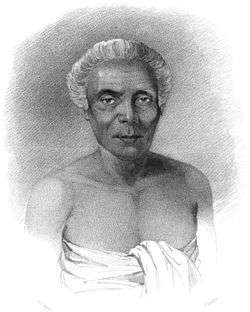

A drawing of a Samoan village made in 1839 by Alfred Agate during the Wilkes Expedition. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Land: ~20 marines ~50 sailors Sea: 1 sloop-of-war 1 schooner | unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| none | unknown | ||||||

Following the murder of an American sailor on the island of Upolu, Samoa, two United States Navy warships were dispatched to investigate. When the principal local chief would not hand over those suspected of the murder, they bombarded one village and went ashore and burned down others.[1]

Background

The American expedition of discovery first arrived off Upolu in October 1839 while conducting surveys of the region. Because United States-flagged merchant ships had traded a lot with the natives in the previous decades, Commander Charles Wilkes decided on establishing a treaty with the seven chiefs on the island which would govern future relations. Wilkes then drafted what he called the "commercial regulations" that, among other things, provided that the Samoans would hand over any natives found guilty of murdering foreigners. An incident had occurred a few years before in which the followers of Chief Oportuno had killed three sailors from an American merchantman, so Wilkes wanted a treaty to handle such a situation. All of the stipulations were agreed to and were officially signed on November 5, 1839, the same day that James C. William was appointed the American consul to the island. With that accomplished, Commander Wilkes left Upolu to continue his voyage around the world.

Trade with the Samoans went well until about a year later, when the natives at Upolu killed another American.[2]

Bombardment

When Commander Wilkes learned of the death, he detached two vessels from his squadron to sail back to Samoa. The twenty-two gun sloop-of-war USS Peacock and the small two gun schooner USS Flying Fish were under the command of Lieutenant William L. Hudson and Commandant Samuel R. Knox, respectively. The two vessels arrived off Upolu on February 24, 1841. The Americans decided to meet with the principal chief Malietoa to demand that the murderer or murderers be handed over.

Malietoa refused to surrender the suspects, so Lieutenant Hudson decided to land "70 odd men", including a force of no more than twenty marines, and bombard the village of Saulafata. After preparations for battle were completed, the landing party boarded boats and waited off the Peacock's starboard quarter while she and the Flying Fish shelled the Samoans. It was still the morning of February 24 when the American warships opened fire with grapeshot and round shot. The grapeshot had no effect and fell short of target, but the round shot quickly began scoring hits upon the buildings on shore.[3]

The native warriors did not resist the attack in any way, and after the first cannon was fired, they retreated from the beach to gather their families and belongings before fleeing into the jungle. After eighteen shots, the ships ceased firing, and the shore party was sent into Saulafata. There the marines and sailors were divided into three units under Lieutenants William M. Walker of the Marine Corps, De Haven and George F. Emmos, as well as a few midshipmen. Two units began burning the forty of fifty huts with torches, while the third unit remained at the boats. There was no fighting. None of the Samoans were even seen after the first cannon was fired. With Saulafata destroyed, the Americans returned to their ships, but when they got there, Lieutenant Hudson ordered them to return ashore and destroy the villages of Fusi and Sallesesi. So again the party was landed after first receiving "a taste of grog" as encouragement. There were over 100 huts between the two villages, and the second was destroyed in the same manner as the first, without any resistance from the natives. The Americans then returned to the beach and destroyed all the canoes they could find before reboarding their ships and sailing away to rejoin Commander Wilkes.[4]

See also

- Punitive expedition

- First Fiji Expedition

- Second Fiji Expedition

- First Sumatran Expedition

- Second Sumatran Expedition

- Nukapu Expedition

References

- Ellsworth, pg. 144-146

- As part of the commercial regulations, alcohol was banned on the island and all merchant vessels were to receive a paper upon arrival of the regulations, so any drunken conduct was probably not the cause of the affair. (Ellsworth, pg. 144)

- Ellsworth, pg. 145

- Ellsworth, pg. 145-146

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

- Ellsworth, Harry A. (1974). One Hundred Eighty Landings of United States Marines 1800-1934. Washington D.C.: US Marines History and Museums Division.