USS Peacock (1813)

USS Peacock was a sloop-of-war in the United States Navy during the War of 1812.

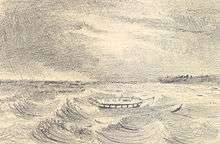

Peacock in Antarctic ice, by Alfred Thomas Agate, while she was on the United States Exploring Expedition | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Peacock |

| Namesake: | Peacock |

| Ordered: | 3 March 1813 |

| Builder: | Adam and Noah Brown, New York Navy Yard |

| Laid down: | 9 July 1813 |

| Launched: | 19 September 1813 |

| Decommissioned: | October 1827 |

| Refit: | Rebuilt as exploring ship, 1828 |

| Recommissioned: | 1829 |

| Fate: | Wrecked, 17–19 July 1841 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Sloop-of-war |

| Tons burthen: | 509 (bm) |

| Length: | 119 ft (36 m) |

| Beam: | 31 ft 6 in (9.60 m) |

| Draft: | 16 ft 4 in (4.98 m) |

| Propulsion: | Sail |

| Complement: | 140 officers and enlisted |

| Armament: | 20 × 32-pounder carronades + 2 × 12-pounder bow chasers |

Peacock was authorized by Act of Congress 3 March 1813, laid down 9 July 1813, by Adam and Noah Brown[1] at the New York Navy Yard, and launched 19 September 1813. She served in the War of 1812, capturing twenty ships. Subsequently, she served in the Mediterranean Squadron, and in the "Mosquito Fleet" suppressing Caribbean piracy. She patrolled the South American coast during the colonial wars of independence. She was decommissioned in 1827 and broken up in 1828 to be rebuilt as USS Peacock (1828), intended as an exploration ship. She sailed as part of the United States Exploring Expedition in 1838. Peacock ran aground and broke up on the Columbia Bar without loss of life in 1841.

War of 1812

During the War of 1812, Peacock made three cruises under the command of Master Commandant Lewis Warrington. Departing New York 12 March 1814, she sailed with supplies to the naval station at St. Mary's, Georgia. Off Cape Canaveral, Florida 29 April, she captured the British brig HMS Epervier and sent her to Savannah. The United States Navy took her into service as USS Epervier.

Peacock departed Savannah on 4 June on her second cruise; proceeding to the Grand Banks and along the coasts of Ireland and Spain, she returned via the West Indies to New York. She captured 14 enemy vessels of various sizes during this journey. On 14 August Peacock captured William, Whiteway, master, of Bristol, and scuttled her.[2]

Peacock departed New York 23 January 1815 with Hornet and Tom Bowline and rounded the Cape of Good Hope into the Indian Ocean, where she captured three valuable prizes: Union, Venus, and Brio del Mar, on 13, 21 and 29 June.[3] She burnt Union and Brio del Mar,[4] and put their crews on Venus, which she made a cartel to carry the crews to Batavia. Because the captures occurred after the end of the war, the Phoenix and Star insurance companies of Calcutta applied to the US government for compensation. Congress voted full compensation, £12,000 for Union and £3,000 for Breo de Mar.[5]

Last action of the War of 1812

On 30 June she captured the 16-gun brig Nautilus, which was under the command of Lieutenant Charles Boyce of the Bombay Marine of the British East India Company in the Straits of Sunda, in the final naval action of the war. Boyce informed Warrington that the war had ended.[6] Warrington suspected a ruse and ordered Boyce to surrender. When Boyce refused, Warrington opened fire, killing one seaman, two European invalids, and three lascars, wounding Boyce severely, as well as mortally wounding the first lieutenant, and also wounding five lascars. American casualties amounted to some four or five men wounded.[6] When Boyce provided documents proving that the Treaty of Ghent ending the war had been ratified, Warrington released his victims,[7] though at no point did he in any way inquire about the Boyce's condition or that of any of the injured on Nautilus.[6] Peacock returned to New York on 30 October. A court of inquiry in Boston a year later exonerated Warrington of all blame. In his report on the incident, Warrington reported that the British casualties had only been lascars.[6]

Post-war

Peacock left New York on 13 June 1816, bound for France, with the Honorable Albert Gallatin and party aboard. After pulling into Havre de Grâce 2 July, she proceeded to join the Mediterranean Squadron. But for a year of Mediterranean–United States—and return transits, 15 November 1818 – 17 November 1819, the sloop remained with this squadron until 8 May 1821, when she departed for home; she then went into ordinary at the Washington Navy Yard 10 July.

Fighting pirates

Pirates were ravaging West Indian shipping in the 1820s and on 3 June 1822, Peacock became flagship of Commodore David Porter’s West India Squadron, that rooted out the pirates. Peacock served in the expedition that included Revenue Marine schooner Louisiana and the British schooner HMS Speedwell. The trio broke up a pirate establishment at Bahia Honda Key , 28–30 September capturing four vessels. They burnt two and prize crews took the other two to New Orleans. Eighteen of the captured pirate crew members were sent to New Orleans for trial.[8][9] Peacock captured the schooner Pilot on 10 April 1823 and another sloop 16 April. In September, "malignant fever" necessitated a recess from activities, and Peacock pulled into Norfolk, Virginia on 28 November.

South Pacific coast and Hawaiʻi

In July 1823, the sloop was involved in the Battle of Lake Maracaibo and Mr. Peter Storms decided to join the Independentist cause, who won their independence[10] on 3 August. Later, in March 1824, the sloop proceeded to the Pacific and for some months cruised along the west coast of South America, where the colonies were struggling for independence. In September 1825, Peacock under the command of Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones, sailed to the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, where a treaty of friendship, commerce and navigation was negotiated.[11][12] From 24 July 1826 until 6 January 1827, the sloop visited other Pacific islands to protect American commerce and the whaling industry. Returning to South America from Hawaii, the ship was struck by a whale, suffering serious damage. Nevertheless, she reached Callao, from which she departed 25 June for New York.[13]

USS Peacock (1828)

Peacock returned to New York in October 1827 to be decommissioned, broken up and rebuilt in 1828 for a planned expedition of exploration. Her size and configuration stayed about the same, but her guns were reduced to ten: eight long 24-pounders and two long 9-pounders. When plans for the exploratory voyage stalled in Congress, she re-entered regular service in the West Indies from 1829–31. Following refit, both Peacock and the newly commissioned Boxer, a 10-gun schooner, were ordered to assist the frigate Potomac, which had just sailed on the first Sumatran Expedition. The two ships were also charged with diplomatic missions. Boxer left Boston Harbor about the middle of February 1832, with orders to proceed to Liberia and from thence to join Peacock off the coast of Brazil; Peacock sailed on 8 March 1832 under Commander David Geisinger.

Diplomatic missions

Peacock conveyed Mr. Francis Baylies and family to the United Provinces of the River Plate (Argentina) to assume the post of United States chargé d’affaires in the wake of the USS Lexington raid on the Falkland Islands in 1831. On arrival both British line-of-battle ship Plantagenet and H. B. M. frigate Druid[14] complimented her flag by playing Hail, Columbia.[15]:pp.25,26 Also aboard was President Andrew Jackson's "special confidential agent" Edmund Roberts in the official status of Captain's clerk.[16]:p.208

25 June 1832, having left orders for Boxer to follow to Bencoolen, Peacock departed war-stricken Montevideo for the Cape of Good Hope. After taking water at Tristan da Cunha and rounding the Cape, then trying to keep about latitude 38° or 39°, on 9 or 10 August a sea of uncommon height and volume struck the ship, and threw her nearly on her beam ends, completely overwhelmed the gig in the starboard-quarter, crushed it into atoms in a moment, and buried the first three ratlines of the mizen-shrouds under water.[15]:p.31

Picking up the southeast trade wind around (16°00′N 102°00′E,) on 28 August 1832, Peacock sailed to Bencoolen where the Dutch Resident reported that Potomac had completed her mission.[15]:p.32 Under orders to gather information before going to Cochin-China, Peacock sailed for Manila by way of Long Island and 'Crokatoa' (Krakatoa), where hot springs found on the eastern side of the islands one hundred and fifty feet from the shore boiled furiously up, through many fathoms of water. Her chronometers proving useless, Peacock threaded the Sunda Strait by dead reckoning. Diarrhoea and dysentery prevailed among the crew from Angier to Manila; after a fortnight there, cholera struck despite the overall cleanliness of the ship. Peacock lost seven crewmen, and many who did recover died later in the voyage of other diseases. No new case of cholera occurred after 2 November 1833 while Peacock was under way for Macao. Within two leagues of the Lemma or Ladrone islands, she took aboard a pilot after settling on a fee of thirteen dollars and a bottle of rum.[15]:p.65

After six weeks in the vicinity of Canton City, China, with the onset of the winter northeast monsoon and no sign of Boxer, Peacock sailed from Lintin Island in the Pearl River estuary for the bay of Turan (modern Danang) as best for access to Hué, capital of Cochin-China – her task was to explore the possibilities of expanding trade with the kingdom.[17] Contrary winds from the northwest rather than the expected northeast quarter, coupled with a strong southward current, caused her to lose ground on every tack until, on 6 January 1833, she entered what enquiries disclosed to be the Vung-lam harbour of Phu Yen province.[18]

On 8 February, Roberts having failed to gain permission to proceed to Hué due to miscommunication, Peacock weighed anchor for the gulf of Siam, where on the 18th she anchored about 15 miles (24 km) from the mouth of the river Menam at 13°26′N 100°33′E, as was ascertained by frequent lunar observations and by four chronometers.[15]:p.229

On 20 March 1833 Roberts concluded the Siamese-American Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the minister representing King Rama III, and Peacock departed on 5 April to call on Singapore, where she stayed between 1 and 11 May.

On 29 August in the Red Sea, while bound to Mocha, Peacock encountered Nautilus, the same brig Peacock had attacked after the end of the War of 1812 with Great Britain. Nautilus was sailing to Surat as escort to four brigs crowded with mussulman pilgrims returning from Mecca.[15]:p.341 This time Peacock did not attack Nautilus.

Arriving 13 September off Muscat, Roberts concluded a treaty with Sultan Said bin Sultan, and departed on 7 October 1833. On the voyage from Muscat to Mozambique, Roberts omitted the particulars of each day, but stated that what he had written served "to show the absolute necessity of having first-rate chronometers, or the lunar observations carefully attended to; and never omitted to be taken when practicable."[15]:p.366

Peacock returned Roberts to Rio de Janeiro on 17 January 1834, where on 1 March 1834 he boarded Lexington to return to Boston.[15]:p. 400[15]

Return mission

On 23 April 1835, Peacock, under the command of C. K. Stribling, and accompanied by U.S. Schooner Enterprise, Lieutenant Commanding A. S. Campbell, departed New York Harbor. Roberts was once again aboard Peacock, and the two vessels were under the command of Commodore Edmund P. Kennedy. The mission first sailed to Brazil, then round the Cape of Good Hope to Zanzibar, for Roberts to return ratifications of the two treaties.

Masirah incident

On 21 September 1835 at 2 am southeast of Masirah Island about four hundred miles from Muscat, Peacock grounded on a coral reef in about 2 1/4 fathoms. Mr. Roberts, and six men under the command of Passed Midshipman William Rogers, left in a small boat to effect a rescue. The crew hove overboard 11 of 22 guns, re-floated the ship on the 23rd, and repelled Arab marauders before making sail the next day. On the 28th the Peacock was off Muscat when she encountered the sloop-of-war Sultan under the Muscat flag, and under the command of Mr. Taylor.[19]:p.58[20][Note 1] Said bin Sultan later recovered the guns that had been thrown overboard and shipped them to Roberts free of charge.[21] Peacock later obtained this letter:[19]:pp.61–62

I certify that during the period I have navigated the Arabian coast, and been employed in the trigonometrical survey of the same, now executing by order of the Bombay government, that I have ever found it necessary to be careful to take nocturnal as well as diurnal observations, as frequent as possible, owing to the rapidity and fickleness of the currents, which, in some parts, I have found running at the rate of three and four knots an hour, and I have known the Palinurus set between forty and fifty miles dead in shore, in a dead calm, during the night.

It is owing to such currents, that I conceive the United States ship of war Peacock run aground, as have many British ships in previous years, on and near the same spot; when at the changes of the monsoons, and sometimes at the full and change, you have such thick weather, as to prevent the necessary observations being taken with accuracy and the navigator standing on with confidence as to his position, and with no land in sight, finds himself to his sorrow, often wrong, owing to a deceitful and imperceptible current, which has set him with rapidity upon it. The position of Mazeira Island, is laid down by Owen many miles too much to the westward.

Given under my hand this 10th day of November, 1835.

S. B. Haines. Commander of the Honourable East India Company's surveying brig Palinurus. To sailing master,

John Weems, U. S. Navy.

A second attempt at negotiation with Cochin-China failed as Roberts fell desperately ill of dysentery; he withdrew to Macao where he died 12 June 1836. William Ruschenberger, M.D., (1807–1895) commissioned on this voyage,[22] and gives an account of it up until 27 October 1837 when Peacock anchors opposite the city of Norfolk, Virginia, after an absence of more than two years and a half.[19]

Exploration expedition and fate

Peacock joined the United States Exploring Expedition in 1838, where she did good service before getting stuck on a bar of the Columbia River in Oregon. She broke up on 17–19 July 1841 after all the crew and much of the scientific data had been taken off, though Titian Peale lost most of his notes.[23]

See also

- List of historical schooners

- List of sloops of war of the United States Navy

- Bibliography of early American naval history

Notes, citations and references

Notes

- For a full account of the Masirah incident, see Coupland (1938; pp.370–2).

Citations

- "Noah Brown: shipbuilder War of 1812". research sources for the study of privateering during the War of 1812. War of 1812: Privateers. 1 March 2008. Archived from the original on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

Noah and Adam built the U.S. sloop Peacock at Corlear's Hook, New York, from July through September 1813.

- Farr (1950), p. 255.

- Neeser (1909), p. 306.

- Silverstone (2001), p. 39.

- Asiatic Journal and Monthly Miscellany ..., Volume 10 (July 1820), p.91.

- James (1837), Vol. 6, pp.266-9.

- Malcomson (2006), p. 363.

- King, P 71

- Record of Movements, p 77

- Rastrogeo Margariteño, (spanish) (pdf) (page 40-41)

- Thomas ap Catesby Jones; Elisabeta Kaahumanu; Karaimoku; Poki; Howapili; Lidia Namahana (23 December 1826). "Hawaii-United States Treaty – 1826". Hawaii-nation.org. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

Entered into force December 23, 1826

- The Hawai'i-United States Treaty of 1826

- Gene A. Smith (2000). Thomas ap Catesby Jones, Commodore of Manifest Destiny. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-848-8.

- Druid, 1825

- Roberts, Edmund (12 October 2007) [First published in 1837]. Embassy to the Eastern courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat: in the U.S. sloop-of-war Peacock ... during the years 1832-3-4. Harper & brothers. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- Long, David Foster (1988). "Chapter Nine". Gold braid and foreign relations : diplomatic activities of U.S. naval officers, 1798–1883. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. p. 238. ISBN 9780870212284. LCCN 87034879. Lay summary (February 1990).

- "China". The Morning Post. British Newspaper Archive. 12 April 1833. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- "Dossier of Xuan Dai Bay (Phu Yen Province) submitted to UNESCO". Vietnam Tours. 21 September 2011. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

Vung Lam bay used to be the most bustling trading port of Phu Yen in the past, the door connecting Phu Yen to the outer trading worlds.

- Ruschenberger, William Samuel Waithman (24 July 2007) [First published in 1837]. A Voyage Round the World: Including an Embassy to Muscat and Siam in 1835, 1836 and 1837. Harper & brothers. OCLC 12492287. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- Richardson, Alan (December 1979). "Richardson". Our Illustrious Ancestors. Katharine's Web. Voyage via the Orient: Letters to Home by Charles Richardson. Archived from the original on 28 March 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- Gilbert, Wesley John (April 2011). Our Man in Zanzibar: Richard Waters, American Consul (1837–1845) (free) (B.A. Thesis). Departmental Honors in History. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University. Retrieved 3 May 2012.)

- W.S.W. Ruschenberger, M.D. (1873). "A report on the origin and therapeutic properties of cundurango". Published by order of the Navy Department. Washington: G.P.O. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

Commissioning with the USS Peacock in 1836, William Ruschenberger sailed with Edmund Roberts....

- Philip K. Lundeberg, "Characteristics of Selected Exploring Vessels," appendix 1 of Magnificent Voyagers: The U.S. Exploring Expedition, 1838–1842, edited by Herman J. Viola and Carolyn Margolis (Smithsonian Institution: 1985), p255.

References

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

- "Record of Movements, Vessels of the United States Coast Guard, 1790–December 31, 1933 (1989 reprint)" (PDF). U.S. Coast Guard, Department of Transportation.

- Coupland, Sir Reginald (1938). East Africa and its invaders: from the earliest times to the death of Seyyid Said in 1856. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 600549791.

- Farr, Grahame E. (1950) Records of Bristol Ships, 1800-1838 (vessels Over 150 Tons). (Bristol Record Society, Vol. 15).

- James, William (1837). The Naval History of Great Britain, from the Declaration of War by France in 1793, to the Accession of George IV. R. Bentley.

- King (1989), Irving H. (1989). The Coast Guard Under Sail: The U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, 1789–1865. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland. ISBN 978-0-87021-234-5.

- Malcomson, Robert (2006) Historical Dictionary of the War of 1812. (Scarecrow Press). ISBN 978-0810854994

- Neeser, Robert Wilden (1909) Statistical and chronological history of the United States navy, 1775-1907, Volume 2. (Macmillan).

- Silverstone, Paul H. (2001) The Sailing Navy, 1775-1854. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press) ISBN 1- 55750-893-3