Boeotia

Boeotia, sometimes alternatively Latinised as Boiotia, or Beotia (/biˈoʊʃiə, -ʃə/; Greek: Βοιωτία, Modern Greek: [vi.oˈti.a], Ancient Greek: [boj.jɔː.tí.a]; modern transliteration Voiotía, also Viotía, formerly Cadmeis), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Central Greece. Its capital is Livadeia, and its largest city is Thebes.

Boeotia Περιφερειακή ενότητα Βοιωτίας | |

|---|---|

Municipalities of Boeotia | |

Boeotia within Greece | |

| Coordinates: 38°25′N 23°05′E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Region | Central Greece |

| Capital | Livadeia |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,211 km2 (1,240 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 117,920 |

| • Density | 37/km2 (95/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal codes | 32x xx, 190 12 |

| Area codes | 226x0 |

| ISO 3166 code | GR-03 |

| Car plates | ΒΙ |

| Website | www |

Boeotia was also a region of ancient Greece, since before the 6th century BC.

Geography

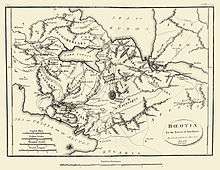

Boeotia lies to the north of the eastern part of the Gulf of Corinth. It also has a short coastline on the Gulf of Euboea. It bordered on Megaris (now West Attica) in the south, Attica in the southeast, Euboea in the northeast, Opuntian Locris (now part of Phthiotis) in the north and Phocis in the west.

The main mountain ranges of Boeotia are Mount Parnassus in the west, Mount Helicon in the southwest, Cithaeron in the south and Parnitha in the east. Its longest river, the Cephissus, flows in the central part, where most of the low-lying areas of Boeotia are found.

Lake Copais was a large lake in the center of Boeotia. It was drained in the 19th century. Lake Yliki is a large lake near Thebes.

Origins

The earliest inhabitants of Boeotia, associated with the city of Orchomenus, were called Minyans. Pausanias mentions that Minyans established the maritime Ionian city of Teos,[1] and occupied the islands of Lemnos and Thera. The Argonauts were sometimes referred to as Minyans. Also, according to legend the citizens of Thebes paid an annual tribute to their king Erginus.[2] The Minyans may have been proto-Greek speakers. Although most scholars today agree that the Myceneans descended from the Minyans of the Middle Helladic period, they believe that the progenitors and founders of Minyan culture were an indigenous people.[3] The early wealth and power of Boeotia is shown by the reputation and visible Mycenean remains of several of its cities, especially Orchomenus and Thebes.

The origin of the name "Boeotians" may lie in the mountain Boeon in Epirus.[4]

Some toponyms and the common Aeolic dialect indicate that the Boeotians were related to the Thessalians. Traditionally, the Boeotians are said to have originally occupied Thessaly, the largest fertile plain in Greece, and to have been dispossessed by the north-western Thessalians two generations after the Fall of Troy (1200 BC). They moved south and settled in another rich plain, while others filtered across the Aegean and settled on Lesbos and in Aeolis in Asia Minor. Others are said to have stayed in Thessaly, withdrawing into the hill country and becoming the perioikoi, ("dwellers around").[5]

Although far from Anthela, which lay on the coast of Malis south of Thessaly in the locality of Thermopylae, Boeotia was an early member of the oldest religious Amphictyonic League (Anthelian)[6] because her people had originally lived in Thessaly.[7]

Legends and literature

Many ancient Greek legends originated or are set in this region. The older myths took their final form during the Mycenean age (1600–1200 BC) when the Mycenean Greeks established themselves in Boeotia and the city of Thebes became an important centre. Many of them are related to the myths of Argos, and others indicate connections with Phoenicia, where the Mycenean Greeks and later the Euboean Greeks established trading posts.

Important legends related to Boeotia include:

- Eros, worshiped by a fertility cult in Thespiae

- The Muses of Mount Helicon

- Ogyges and the Ogygian deluge

- Cadmus, who was said to have founded Thebes and brought the alphabet to Greece

- Dionysus and Semele

- Narcissus

- Heracles, who was born in Thebes

- The Theban Cycle, including the myths of Oedipus and the Sphinx, and the Seven against Thebes

- Antiope and her sons Amphion and Zethus

- Niobe

- Orion, who was born in Boeotia and said to have fathered 50 sons with the daughters of a local river god.

Many of these legends were used in plays by the tragic Greek poets, Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides:

- Aeschylus's Seven Against Thebes

- Sophocles's Oedipus Rex, Oedipus at Colonus, and Antigone, known as the Theban plays

- Euripides's Bacchae, Phoenician Women, Suppliants, and Heracles

They were also used in lost plays such as Aeschylus's Niobe and Euripides's Antiope.

Boeotia was also notable for the ancient oracular shrine of Trophonius at Lebadea. Graea, an ancient city in Boeotia, is sometimes thought to be the origin of the Latin word Graecus, from which English derives the words Greece and Greeks.

History

Boeotia had significant political importance, owing to its position on the north shore of the Gulf of Corinth, the strategic strength of its frontiers, and the ease of communication within its extensive area. On the other hand, the lack of good harbours hindered its maritime development.

The importance of the legendary Minyae has been confirmed by archaeological remains (notably the "Treasury of Minyas"). The Boeotian population entered the land from the north possibly before the Dorian invasion. With the exception of the Minyae, the original peoples were soon absorbed by these immigrants, and the Boeotians henceforth appear as a homogeneous nation. Aeolic Greek was spoken in Boeotia.

In historical times, the leading city of Boeotia was Thebes, whose central position and military strength made it a suitable capital;[8] other major towns were Orchomenus, Plataea, and Thespiae. It was the constant ambition of the Thebans to absorb the other townships into a single state, just as Athens had annexed the Attic communities. But the outlying cities successfully resisted this policy, and only allowed the formation of a loose federation that, initially, was merely religious.[8]

While the Boeotians, unlike the Arcadians, generally acted as a united whole against foreign enemies, the constant struggle between the cities was a serious check on the nation's development. Boeotia hardly figures in history before the late 6th century BC.

Previous to this, its people are chiefly known as the makers of a type of geometric pottery, similar to the Dipylon ware of Athens. In about 519 BC, the resistance of Plataea to the federating policy of Thebes led to the interference of Athens on behalf of the former; on this occasion, and again in 507 BC, the Athenians defeated the Boeotian levy.

Fifth century BC

During the Persian invasion of 480 BC, Thebes assisted the invaders. In consequence, for a time, the presidency of the Boeotian League was taken from Thebes, but in 457 BC the Spartans reinstated that city as a bulwark against Athenian aggression after the Battle of Tanagra. Athens retaliated with a sudden advance upon Boeotia, and after the victory at the Battle of Oenophyta took control of the whole country, taking down the wall the Spartans had built. With the victory the Athenians also occupied Phocis, the original source of the conflict, and Opuntian Locris.[9] For ten years the land remained under Athenian control, which was exercised through the newly installed democracies; but in 447 BC the people revolted, and after a victory at the Battle of Coronea regained their independence.[8]

In the Peloponnesian War the Boeotians fought zealously against Athens. Although slightly estranged from Sparta after the peace of Nicias, they never abated their enmity against their neighbours. They rendered good service at Syracuse and at the Battle of Arginusae in the closing years of the Pelopennesian War; but their greatest achievement was the decisive victory at the Battle of Delium over the Athenian army (424 BC) in which both their heavy infantry and their cavalry displayed unusual efficiency.

Boeotian League

About this time the Boeotian League comprised eleven groups of sovereign cities and associated townships, each of which elected one Boeotarch or minister of war and foreign affairs, contributed sixty delegates to the federal council at Thebes, and supplied a contingent of about 1000 infantry and 100 cavalry to the federal army. A safeguard against undue encroachment on the part of the central government was provided in the councils of the individual cities, to which all important questions of policy had to be submitted for ratification. These local councils, to which the propertied classes alone were eligible, were subdivided into four sections, resembling the prytaneis of the Athenian council, which took it in turns to vote on all new measures.[8][10]

Two Boeotarchs were provided by Thebes, but by 395 BC Thebes was providing four Boeotarchs, including two who had represented places now conquered by Thebes such as Plataea, Scolus, Erythrae, and Scaphae. Orchomenus, Hysiae, and Tanagra each supplied one Boeotarch. Thespiae, Thisbe, and Eutresis supplied two between them. Haliartus, Lebadea and Coronea supplied one in turn, and so did Acraephia, Copae, and Chaeronea.[11]

Fourth century BC

Boeotia took a prominent part in the Corinthian War against Sparta, especially in the battles of Haliartus and Coronea (395–394 BC). This change of policy was mainly due to the national resentment against foreign interference. Yet disaffection against Thebes was now growing rife, and Sparta fostered this feeling by insisting on the complete independence of all the cities in the peace of Antalcidas (387 BC). In 374, Pelopidas restored Theban dominion[8] and their control was never significantly challenged again. Boeotian contingents fought in all the campaigns of Epaminondas against the Spartans, most notably at the Battle of Leuctra in 371, and in the Third Sacred War against Phocis (356–346 BC); while in the dealings with Philip of Macedon the cities merely followed Thebes.

The federal constitution was also brought into accord with the democratic governments now prevalent throughout the land. Sovereign power was vested in the popular assembly, which elected the Boeotarchs (between seven and twelve in number), and sanctioned all laws. After the Battle of Chaeroneia, in which the Boeotian heavy infantry once again distinguished itself, the land never again rose to prosperity.[8]

Hellenistic period

The destruction of Thebes by Alexander the Great (335) destroyed the political energy of the Boeotians. They never again pursued an independent policy, but followed the lead of protecting powers. Although military training and organization continued, the people proved unable to defend the frontiers, and the land became more than ever the "dancing-ground of Ares". Although enrolled for a short time in the Aetolian League (about 245 BC) Boeotia was generally loyal to Macedon, and supported its later kings against Rome. Rome dissolved the league in 171 BC, but it was revived under Augustus, and merged with the other central Greek federations in the Achaean synod. The death-blow to the country's prosperity was dealt by the devastations during the First Mithridatic War.[8]

Middle Ages and later

Save for a short period of prosperity under the Frankish rulers of Athens (1205–1310), who repaired the underground drainage channels (καταβόθρα katavóthra) of Lake Kopais and fostered agriculture, Boeotia long continued in a state of decay, aggravated by occasional barbarian incursions. The first step toward the country's recovery was not until 1895, when the drainage channels of Kopais were again put into working order.

Archaeological sites

Orchomenus

In 1880–86, Heinrich Schliemann's excavations at Orchomenus (H. Schliemann, Orchomenos, Leipzig 1881) revealed the tholos tomb he called the "Tomb of Minyas", a Mycenaean monument that equalled the beehive tomb known as the Treasury of Atreus at Mycenae. In 1893, A. de Ridder excavated the temple of Asclepios and some burials in the Roman necropolis. In 1903–05, a Bavarian archaeological mission under Heinrich Bulle and Adolf Furtwängler conducted successful excavations at the site. Research continued in 1970–73 by the Archaeological Service under Theodore Spyropoulos, uncovering the Mycenaean palace, a prehistoric cemetery, the ancient amphitheatre, and other structures.

Pejorative term

Although they included great men such as Pindar, Hesiod, Epaminondas, Pelopidas, and Plutarch, the Boeotian people were portrayed as proverbially dull by the Athenians (cf. Boeotian ears incapable of appreciating music or poetry and Hog-Boeotians, Cratinus.310).[12]

Administration

The regional unit Boeotia is subdivided into 6 municipalities. These are (number as in the map in the infobox):[13]

- Aliartos (2)

- Distomo-Arachova-Antikyra (3)

- Livadeia (1)

- Orchomenos (5)

- Tanagra (6)

- Thebes (Thiva, 4)

Prefecture

Boeotia was created as a prefecture in 1836 (Greek: Διοίκησις Βοιωτίας), again in 1899 (Νομός Βοιωτίας) and again in 1943; in all cases it was split from Attica and Boeotia Prefecture. As a part of the 2011 Kallikratis government reform, the regional unit Boeotia was created out of the former prefecture Boeotia. The prefecture had the same territory as the present regional unit. At the same time, the municipalities were reorganised, according to the table below.[13]

| New municipality | Old municipalities & communities | Seat |

|---|---|---|

| Aliartos | Aliartos | Aliartos |

| Thespies | ||

| Distomo-Arachova-Antikyra | Distomo | Distomo |

| Arachova | ||

| Antikyra | ||

| Livadeia | Livadeia | Livadeia |

| Davleia | ||

| Koroneia | ||

| Kyriaki | ||

| Chaironeia | ||

| Orchomenus | Orchomenus | Orchomenus |

| Akraifnia | ||

| Tanagra | Tanagra | Schimatari |

| Dervenochoria | ||

| Oinofyta | ||

| Schimatari | ||

| Thebes (Thiva) | Thebes | Thebes |

| Vagia | ||

| Thisvi | ||

| Plataies |

Economy

Boeotia is the home of the third largest pasta factory in Europe, built by MISKO, a member of Barilla Group.[14] Also, some of the biggest companies in Greece and Europe have factories in this place. For example, Nestlé and Viohalco have factories in Oinofyta, Boeotia.

Transport

- Greek National Road 1/E75, SE, E, NE

- Greek National Road 3, S, E, Cen., W, NW

- Greek National Road 27, W, SW

- Greek National Road 44, E

- Greek National Road 48, W

Natives of Boeotia

- Bakis

- Corinna

- Epaminondas

- Gorgidas

- Hesiod

- Luke the Evangelist (traditionally location of his death)

- Pelopidas

- Pindar

- Plutarch

- Scamander of Boeotia

See also

References

- Pausanias.Description of Greece 7.3.6

- Bibliotheke 2.4.11 records the origin of the Theban tribute as recompense for the mortal wounding of Clymenus, king of the Minyans, with a cast of a stone by a charioteer of Menoeceus in the precinct of Poseidon at Onchestus; the myth is also reported by Diodorus Siculus, 4.10.3.

- Cambitoglou & Descœudres 1990, p. 7 under "Excavations in the Region of Pylos" by George S. Korrés.

- Sylvain Auroux. History of the language sciences: an international handbook on the evolution.

- L. H .Jeffery (1976). Archaic Greece. The Greek city-states 700-500 BC. Ernest Benn Ltd. London & Tonbridge. pp. 71, 77 ISBN 0-510-03271-0

- The Parian marble. Entry No 5: "When Amphictyon son of Hellen became king of Thermopylae brought together those living round the temple and named them Amphictyones; Entry No 6: Graeces-Hellenes

- L. H . Jeffery (1976). Archaic Greece. The Greek city states c. 700-500 B.C. Ernest Benn Ltd. London & Tonbridge pp. 72, 73 ISBN 0-510-03271-0

-

- Thucydides iv. 76-101

- Xenophon, Hellenica, iii.-vii.

- Strabo, pp. 400-412

- Pausanias ix.

- Theopompus (or Cratippus) in the Oxyrhynchus Papyri, vol v. (London, 1908, No. 842, col 12

- W. M. Leake, Travels in Northern Greece, chs. xi.-xix. (London, 1835)

- H. F. Tozer, Geography of Greece (London, 1873), pp. 233-238

- W. Rhys Roberts, The Ancient Boeotians (Cambridge, 1895)

- E. A. Freeman Federal Government (ed. 1893, London), ch. iv. § 2

- B. V. Head, Historia Nomorum, pp. 291 sqq. (Oxford, 1887)

- W. Larfeld, Sylloge Inscriptionum Boeoticarum (Berlin, 1883). (See also Thebes.)

- Fine, John VA (1983). The Ancient Greeks: A Critical History. Harvard University Press. pp. 354–355.

- Thucydides (v. 38), in speaking of the "four councils of the Boeotians," is referring to the plenary bodies in the various states. (Chisholm 1911)

- Nick Sekunda, The Ancient Greeks, p.27

- The Merriam-Webster New Book of Word Histories, Merriam-Webster, 1 Jan 1991, p.360

- "Kallikratis reform law text" (PDF).

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 October 2010. Retrieved 3 October 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Sources

- Victor Davis Hanson (1999). The Soul of Battle. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Larson, Stephanie L. Tales of epic ancestry: Boiotian collective identity in the late archaic and early classical periods (Historia Einzelschriften, 197). Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 2007. 238 p.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Boeotia. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Bœotia. |

- "Boeotia digital cultural encyclopedia". Foundation of the Hellenic World. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.