Bocaccio rockfish

The bocaccio[lower-alpha 1] (Sebastes paucispinis) is a northeast Pacific species in the Sebastidae (rockfish) family. Other names for this species include salmon grouper, grouper, tom cod (juveniles), and slimy. In Greek, sebastes means "magnificent", and paucispinis is Latin for "having few spines".[6]

| Bocaccio rockfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Courtesy of the Monterey Bay Aquarium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Scorpaeniformes |

| Family: | Sebastidae |

| Genus: | Sebastes |

| Species: | S. paucispinis |

| Binomial name | |

| Sebastes paucispinis Ayres, 1854 | |

Distribution and biology

Bocaccio can be found from Stepovak Bay, Alaska to central Baja California, but is mostly abundant from Oregon to northern Baja California. They have been spotted from various depths from the surface to 1,568 feet (478 m); most live between 150–1,000 feet (46–305 m).[6] Juveniles stay in shallower water because of the protection provided by floating kelp mats or driftwood. Shallow water kelp forests and oil platforms also help these fish avoid danger, as they can use them to dodge and hide from predators. As the fish get older, they to move into deeper, colder water. The Monterey submarine canyon is an ideal place for many marine organisms to inhabit or migrate through, and bocaccio in this canyon can consume multiple marine species such as shellfish (pelagic shrimp and crab), anchovies, sardines, other small rockfishes, and squid.

The bocaccio is one of the larger rockfish and can grow up to 3 feet (0.91 m) in length and live to 45 years. A bocaccio that is 12 inches (300 mm) long is around 3–4 years old and a 2-foot (0.61 m) long fish is 7–8 years old.[7] Females grow faster than males and also live longer. There is a difference in maturity rates from north to south. Southern California bocaccio mature at 14 inches and reproduce at around 18 inches (460 mm), while northern males mature at 22 inches and females at 24 inches. They are viviparous rockfish; in Southern California they spawn their larvae in 2 or more batches and spawning occurs almost all year. In Central and Northern California they spawn from January to May, while further north spawning is restricted to January to March. One female can produce over 2 million eggs per season. Coloration is olive-brown dorsally becoming pink to red ventrally.[8]

Environmental effects

Certain effects of strong and weak upwelling affect the bocaccio's food sources and the survival of its larvae. Larval rockfish are abundant in or near front upwelling fronts.[9] When the water is cold the upwelling is strong with more productivity and warmer water produces a weaker upwelling with a low amount of resources. Also, a weak upwelling may affect reproduction in egg size, egg amount, and egg quality. El Niño and La Niña effect of the upwelling due to the drastic changes in the warmth of water. They also get affected by overfishing.

Conservation

Recreational and commercial fisheries off the coast of California rely heavily on bocaccio. They are caught by trawling, gillnetting and hook and line. Overfishing has occurred over the past decade. Commercial fishermen tend to target bocaccio due to their abundance and longer shelf life. The California Department of Fish and Game has set a regulation limit of 2 bocaccio per day at a minimum length of 10 inches (250 mm). Also, the depths of fishing have decreased now as older and larger Bocaccio tend to stay deeper because the deepest fishermen can fish at is around 240 feet (73 m).

Studies off of Southern California oil platforms show they have produced a slight increase on bocaccio population. Juveniles like to use these platforms as they provide a resemblance of a natural habitat with more protection,[10][11] and because of the availability of plankton. Studies showed that out of eight platforms there was a large amount of young juvenile bocaccio at seven platforms.

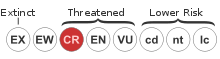

In January 2001 the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) received a petition to list the southern population of bocaccio as a Threatened species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA).[12] In November 2002, NMFS published its recommendation that ESA listing was not warranted.

The southern distinct population segment of bocaccio is a U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service Species of Concern.[13] Species of Concern are those species about which the U.S. Government's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service has some concerns regarding status and threats, but for which insufficient information is available to indicate a need to list the species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act[12]

On October 29, 2007, NMFS received a petition from Mr. Wright to list the Puget Sound DPS of bocaccio under the ESA. NMFS listed the Puget Sound/Georgia basin Distinct population segment as endangered on April 28, 2010.[14] Critical habitat was designated on November 13, 2014.[15]

Notes

References

- Sobel, J. (1996). "Sebastes paucispinus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T20085A9144801. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T20085A9144801.en.

- "Bocaccio". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- "bocaccio". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- "bocaccio". Lexico US Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- "bocaccio". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- Love, Milton (1996). Probably more than you Want to know about the Fishes of the Pacific Coast. Santa Barbara: Really Big Press. pp. 179–182.

- Phillips, Julius B. (1964). Life History Studies on ten species of Rockfish. Marine Resources Operations. pp. 20–23.

- "Boccacio". AFSC Guide to Rockfishes. Alaska Fisheries Science Center, NOAA Fisheries Service. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- Tolimieri, N. (2005). The roles of fishing and climate in the population dynamics of bocaccio rockfish. Ecological applications. 15. pp. 458–468. doi:10.1890/03-5376.

- Love, MS (2006). "The relationships between fish assemblages and the amount of bottom horizontal beam exposed at California oil platforms: fish habitat preferences at man-made platforms and (by inference) at natural reefs". Fishery Bulletin of the Fish and Wildlife Service. 104 (4): 542–549.

- Love, MS (2006). "Potential use of offshore marine structures in rebuilding an overfished rockfish species, bocaccio (Sebastes paucispinis)". Fishery Bulletin of the Fish and Wildlife Service. 104 (3): 383–390.

- "Endangered Species Act (ESA)". Retrieved May 25, 2007.

- "Proactive Conservation Program: Species of Concern". Retrieved May 25, 2007.

- NMFS. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants: Threatened Status for the Puget Sound/Georgia Basin Distinct Population Segments of Yelloweye and Canary Rockfish and Endangered Status for the Puget Sound/Georgia Basin Distinct Population Segment of Bocaccio Rockfish .Federal Register;; v75, (April 28, 2010), 22276-22290.

- NMFS. Endangered and Threatened Species; Designation of Critical Habitat for the Puget Sound/Georgia Basin Distinct Population Segments of Yelloweye Rockfish, Canary Rockfish and Bocaccio.Federal Register;; v79, (November 13, 2014), 68041-68087.