Bob Benge

Robert "Bob" Benge (c. 1762–1794), also known as Captain Benge (or "The Bench" to frontiersmen), was a Cherokee leader in the Lower Towns, in present-day Southwest Virginia during the Cherokee–American wars (1783-1794).

Early life

He was born as Bob Benge about 1762 in the Overhill Cherokee town of Toqua, to a Cherokee woman and a Scots-Irish trader named John Benge, who lived full-time among the Cherokee and had taken a "country wife." They also had a daughter Lucy. Benge stood out physically because of the red hair he inherited from his father. Under the Cherokee matrilineal kinship and clan system, children were considered born into their mother's family and clan. Their mother's eldest brother was considered the most important male figure in their growing up, especially for boys. The children were reared largely in Cherokee culture and identified as Cherokee.

The available sources strongly imply, but do not prove, that young Benge and his sister Lucy were half-siblings of Sequoyah, also known as George Guess. They were related to maternal great-uncles Old Tassel and Doublehead.

When Dragging Canoe and his party moved southwest from eastern Tennessee in 1777, trader John Benge also moved his family to Running Water, one of the Chickamauga Lower Towns in the Piedmont.

Bob Benge, who later became known as "Captain Bench," his half-brother 'The Tail,' and cousin Tahlonteeskee were around 20 years old, they joined their maternal uncle John Watts as warriors to fight against European-American settlers who were encroaching on their territory. These armed confrontations began soon after the Americans had gained independence from Great Britain in their revolutionary war, and began migrating over the Appalachian Mountains to settle in Cherokee territory.

Exploits as a warrior

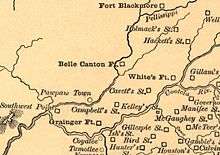

While living at Running Water (now Whiteside, Tennessee), Benge had met members of the Shawnee band of Chiksika and his brother Tecumseh. Benge often took part in their raids and forays against the Americans. In one of the early raids, in spring 1777, Benge is said to have captured two women while raiding near Fort Blackmore, Virginia.[1]

Afterward he often ran with warriors led by Doublehead out of Coldwater Town at the head of Muscle Shoals on the Tennessee River (now in northern Alabama). He is credited with saving the population of the town of Ustally in 1788, which American John Sevier had slated for destruction.

Benge raided as far north as the Ohio River, deep into southwestern Virginia, all of the Washington District of North Carolina, and southeast into Georgia and South Carolina. These included a joint raid between his party and that of Doublehead into the Kentucky hunting grounds.

Brown family

Benge was at Running Water when word came that the Cherokee had reached agreement with John Sevier to exchange hostages. The Brown family was mentioned by name, a group of settlers taken captive in 1788 when they reached Nickajack, after passing through the Five Lower Towns on the Tennessee River. Only three of the surviving Brown family were still held by the Cherokee; the other three had been passed to the Muscogee.

Joseph Brown and his sister Polly were brought immediately to Running Water, but when runners were sent to Crow Town to retrieve Jane, their youngest sister, her owner refused to surrender her. Benge mounted his horse and hefted his famous axe, saying, "I will bring the girl, or the owner's head". The next morning he returned with Jane. The three were later transferred to Sevier at Coosawattee.

Cavett's Station

Benge came to a parting of the ways with his former close ally, Doublehead, over an incident at Cavett's Station. In 1793 John Watts led a raid on the Holston River settlements, aiming at White's Fort (now Knoxville, Tennessee). There, Benge negotiated the surrender of the garrison and its defenders with the promise of safe passage. Doublehead and his band violated the parole by attacking and killing them all: men, women, and children, as soon as they were outside the small fort. This was over the pleas of Benge, Watts, and James Vann to honor the agreement. Benge never operated again with Doublehead after the incident. The massacre also contributed to a bitter animosity between Doublehead and Vann that led to a division between the Upper and Lower Towns after the end of the wars in 1794.

Death

Benge raided as far as the westernmost counties of Virginia, attacking Gate City, Virginia in 1791, and Moccasin Gap and Kane's Gap on Powell Mountain in 1793.[2]

He was killed April 6, 1794 in an ambush in what is in what is now Wise County, Virginia during an extended raid deep into enemy-held territory, while escorting prisoners captured from a settlement earlier in the day back to the Lower Towns. The militia took his scalp and sent it to the Governor of Virginia, Henry Lee III, who sent it on to President George Washington. Credit for killing Benge went to militia leader Vincent Hobbs Jr, son of one of the original white settlers of current Lee County, Virginia.

Sources

- Robert Addison, History of Scott County, Virginia p. 83.

- Addison, p. 3.

Notes

- American State Papers, Indian Affairs, Vol.1, 1789-1813, Congress of the United States, Washington,DC, 1831-1838.

- Evans, E. Raymond. "Notable Persons in Cherokee History: Bob Benge". Journal of Cherokee Studies, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 98–106. (Cherokee: Museum of the Cherokee Indian, 1976).

- Moore, John Trotwood and Austin P. Foster. Tennessee, The Volunteer State, 1769-1923, Vol. 1, pp. 228–231. (Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1923).