Vasily Blyukher

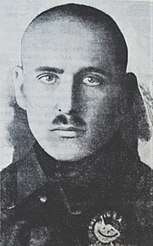

Vasily Konstantinovich Blyukher (Russian: Василий Константинович Блюхер) also spelled Bliukher, Blücher, etc. (1 December 1889 – 9 November 1938) was a Soviet military commander and Marshall of the Soviet Union.

Vasily Blyukher | |

|---|---|

Blyukher as Marshal of the Soviet Union | |

| Birth name | Vasily Konstantinovich Gurov |

| Born | 1 December 1889 Barschinka, Russian Empire |

| Died | 9 November 1938 (aged 48) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Buried | Donskoi Cemetery |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1914–1915 1917–1938 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | Special Red Banner Far Eastern Army |

| Battles/wars | World War I Russian Civil War Sino-Soviet conflict Battle of Lake Khasan Soviet–Japanese border conflicts |

| Awards | Order of Lenin (2) Order of the Red Banner (4) Order of the Red Star |

| Signature |  |

Early history

Blyukher was born into a Russian peasant family named Gurov in the village of Barschinka in Yaroslavl Governorate. In the 19th century a landlord gave the nickname Blyukher to the Gurov family in commemoration of the famous Prussian Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher (1742–1819). As a teenager, he was employed at a machine works, but was arrested in 1910 for leading a strike, and sentenced to two years, eight months in prison.[1] In 1914, Vasily Gurov — who later formally assumed Blyukher as his surname — was drafted into the army of the Russian Empire as a corporal but in 1915 was seriously wounded in the Great Retreat, and excused from military service.[2] He then went to work in a factory in Kazan, where he joined the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. He took part in the Russian Revolution of 1917 in Samara.[3]

Civil War

In late November 1917 he was sent into Chelyabinsk as a Red Guard commissar to suppress Alexander Dutov's revolt. Blyukher joined the Red Army in 1918 and was soon a commander. During the Russian Civil War he was one of the outstanding figures on the Bolshevik side. After the Czech Legion Revolt started, in August–September 1918, the 10,000-strong South Urals Partisan Army under Blyukher's command marched 1,500 km in 40 days of continuous fighting to attack the White forces from the rear, then join with regular Red Army units. For this achievement in September 1918 he became the first recipient of the Order of the Red Banner (later he was awarded it four more times: twice in 1921 and twice in 1928),[3] his citation saying: "The raid made by Comrade Blyukher forces under impossible conditions can only be equated with Suvorov's crossings in Switzerland." After the force rejoined the Red Army lines in the 3rd Red Army area, Blyukher's force was reorganised as the 51st Rifle Division, which he later led to further triumphs against Baron Wrangel in November 1920. After the Civil War he served as military commander of the Far Eastern Republic from 1921–22. From December 1921, he took personal command of the campaign to remove the remnants of anti-Bolshevik forces east of the Amur river. In 1922−24, he was commander of the Petrograd military district.

Far East command

_and_Mongolia.tif.jpg)

From 1924–27 Blyukher was a Soviet military adviser in China, where he used the name Galen[4] (after the name of his wife, Galina) while attached to Chiang Kai-shek's military headquarters. He was responsible for the military planning of the Northern Expedition which began the Kuomintang unification of China. Among those he instructed in this period was Lin Biao, later a leading figure in the Chinese People's Liberation Army. Chiang allowed Blyukher to "escape" after his anti-communist purge.[5] On his return he was given command of the Ukraine military district, and then in 1929 he was transferred to the vitally important military command in the Far Eastern Military District, known as the Special Red Banner Far Eastern Army (OKDVA).

Based at Khabarovsk, Blyukher exercised a degree of autonomy in the Far East unusual for a Soviet military commander. With Japan steadily extending its grip on China and hostile to the Soviet Union, the Far East was an active military command. In the Russo-Chinese Chinese Eastern Railroad War of 1929–30 he defeated Chinese warlord forces in a quick campaign. For this outstanding achievement he became the first recipient of the Order of the Red Star in September 1930.[3] In 1935 he was made a Marshal of the Soviet Union. From July to August 1938 he commanded the Soviet Far East Front in a less decisive action against the Japanese at the Battle of Lake Khasan, on the border between the Soviet Union and Japanese-occupied Korea.

Soviet Purges and death

The importance of the Far East Front gave Blyukher a certain degree of immunity from Stalin's purge of Red Army command, which had begun in 1937 with the execution of Mikhail Tukhachevsky—in fact, Blyukher had been a member of the tribunal that convicted Tukhachevsky. On 15 June 1938, three days after the head of the Far Eastern NKVD Genrikh Lyushkov defected to Japan, Blyukher visited NKVD headquarters in Moscow, seeking information about the defector and about the potential consequences of his disappearance. He met the deputy head of the NKVD, Mikhail Frinovsky,[6] who appears to have reassured him that he would not be held responsible for letting Lyushkov cross the Manchurian border. On 17 June, Frinovsky and the head of the Red Army political directorate, Lev Mekhlis, were dispatched to the Far East to conduct mass arrests, and to spy on Blyukher. He was arrested on 22 October, by which time Frinovsky had been dismissed and the NKVD was effectively controlled by Lavrentiy Beria.

It was long believed that Blyukher was secretly tried, convicted of spying for Japan, and executed. In 1939 Chiang inquired about Blyukher's whereabouts in a meeting with Stalin, and asked if he could return to help the Nationalists. Stalin replied that the general had been executed for helping a Japanese spy.[7] However, in 1989, Izvestia reported that he had refused to confess, and was beaten to death on 9 November 1938.[8] He was rehabilitated in 1956.

He continues to be a popular figure in Russia, and a documentary film on his life and several publications by family members have appeared.[9]

Honours and awards

- Two Orders of Lenin (1931, 1938)

- Order of Red Banner of RSFSR, three times

- Resolution of the Central Executive Committee on 30 September 1918, presented 11 May 1919 by the Special Representative at the headquarters of the Central Executive Committee of the 3rd Army on the Eastern Front;

- Order 197 of 14 June 1921—for the battles on the Eastern Front, the 30th Infantry Division;

- Order 221 of RVSR, 20 June 1921—for the assault on Perekop at the Perekop Isthmus by 51st Infantry Division;

- Order of Red Banner of the USSR, twice

- Order RVS USSR 664 of 25 October 1928—for the defence of the Kakhovka bridgehead;

- Order RVS USSR 101 1928—in commemoration of the 10th anniversary of the Red Army;

- Order of the Red Star(1930)

- Jubilee Medal «XX Years of the Workers' and Peasants' Red Army» (1938)

- Badge "5 years of the Cheka-GPU" (1932)

- Cross of St. George, 3rd and 4th classes

- Medal of St. George

References

- O.Yu. Shmidt; Bukharin N.I.; et al., eds. (1927). Большая советская энциклопедия volume 6. Moscow. p. 537.

- W. Bruce Lincoln, Red Victory: A History of the Russian Civil War (Da Capo: 1999, repr. of Simon & Schuster, 1989), p. 443.

- Great Russian Encyclopedia (2005), Moscow: Bol'shaya Rossiyskaya enciklopediya Publisher, vol. 3, p. 618.

- Adam Krzyżanowski. Raj doczesny komunistów. Arcana, Kraków 2008, p. 269. ISBN 978-83-60940-24-2

- "Generalissimo and Madame Chiang Kai-shek". TIME. Jan 3, 1938. Retrieved May 22, 2011.

- Jansen, Marc and Petrov, Nikita (2002). Stalin's Loyal Executioner: People's Commissar Nikolai Ezhov, 1895–1940. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-8179-2902-2.

- Jonathan Fenby, The Penguin History of Modern China, 2008, page 190

- Getty, J Arch and Naumov, Oleg V. (2010). The Road to Terror, Stalin and the Self-Destruction of the Bolsheviks, 1932–1939. New Haven: Yale U.P. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-300-10407-3.

- http://www.alacona.com/productimages/auto65.html

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Vasily Blyukher |