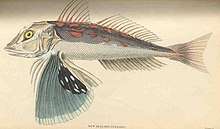

Bluefin gurnard

The bluefin gurnard or Pacific red gurnard (Chelidonichthys kumu) is a species of fish in the family Triglidae, the sea robins and gurnards. Its Maori names are Kumukumu and Pūwahaiau. It is found in the western Indian Ocean and the western Pacific Ocean, being common around Australia and New Zealand at depths down to 200 metres (660 ft).

| Chelidonichthys kumu | |

|---|---|

| |

| New Zealand Gurnard, Chelidonichthys kumu | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Scorpaeniformes |

| Family: | Triglidae |

| Genus: | Chelidonichthys |

| Species: | C. kumu |

| Binomial name | |

| Chelidonichthys kumu (G. Cuvier, 1829) | |

This fish is edible for humans.

Description

.jpg)

The red gurnard is a bottom-dwelling fish known for its bright red body and large, colorful pectoral fins with a large black eye-spot in the center and surrounded by a bright blue edge (Eichelsheim, 2010; Rainer & Reyes, 2019). Its natural color is a splotchy pale brown, generally only becoming red when stressed and the belly is paler or even white (Lang, 2000).

It has a boxy, bony head which is protected by backwards-facing spines along the front of the snout and around the eye as well as on the hind margin of the operculum (Ayling & Cox, 1982) and tapers into a laterally elongated body with 33-35 vertebrae.

There are 8-10 gill rakers and 70-80 scales on its lateral line, which is uninterrupted. Its two tall, triangular dorsal fins have a total of 15-16 soft rays and 9-10 spines. There is no adipose fin. The anal fin has 14-16 soft rays and no spines.

The red gurnard's large, fan-like pectoral fins are one of two pairs with 13-14 soft rays and its pelvic fin has 5 soft rays and a single spine. The pectoral fins’ first three rays are modified and separated from the rest of the fin. They are used as sensory organs, sometimes referred to as “fingers” (Powell, 1947), permitting it to probe the sea bottom to detect prey buried in the sand or the mud (Ayling & Cox, 1982; Francis 2012). These spectacular fins make the red gurnard look like a butterfly of the sea, however their role is not entirely known. They could be used to attract a mate or frighten off predators (Ayling & Cox, 1982). These fan-like fins can also be used to give stability during swimming (Francis, 2012).

Distribution

Natural global range

The red gurnard can be found throughout many central tropical and temperate Indo-West Pacific waters (Elder, 1976). It is commonly found along the coasts of New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, and many islands in the South Pacific. It is unsure whether or not previous records from Japan, Korea, China, and the Hawaiian Islands are mis-identifications (NIWA, 2012; Rainer & Reyes, 2019; Roberts, et al., 2015).

New Zealand range

The red gurnard is the most common gurnard in New-Zealand (Lang, 2000). It is found in all the coastal waters around both the north and south islands (FAO,1981; Roberts, et al., 2015) except the southern fiords (Eichelsheim, 2010; Elder, 1976; Powell, 1947), and also Stewart, the Chathams, and Kermadec Islands (NIWA, 2012). There are large population hotspots around the Bay of Plenty, Hawke Bay, Bank's Peninsula, the Foveaux Strait, the west coast of the North Island, and the north and northwest coasts of the South Island.

Habitat preferences

As a benthic marine fish, the red gurnard prefers shallow coastal waters and may be found from the edge of continental shelves to estuaries and brackish rivers (MacGibbon & Hurst, 2017) with soft bottoms of sand, sandy-shell, or mud (Eichelsheim, 2010; Elder, 1976). This is because they ‘walk’ slowly over the seabed using their first three free-rays (Francis, 2012). They can bury themselves in the substrate, with only the top of their head, their nostrils and eyes exposed in order to surprise prey (Lang, 2000). It is found from shallow waters one meter deep but generally inhabits 100-200m but may have maximum depths of up to 300m (NIWA, 2012; Rainer & Reyes, 2019).

Life cycle/Phenology

Growth

Red gurnard eggs develop for 7 days before hatching (Rainer & Reyes, 2019), and grow rapidly until they reach maturity at 2–3 years old. After reaching maturity growth slows considerably and they move into deeper water shown in a study by Lyon & Horn (2011) where red gurnards found in deeper strata were older and longer on average than those found inshore. Males are smaller than females at around 26 cm and 33 cm respectively and they may live for over 12 years. (Eichelsheim, 2010; Elder, 1976; Francis, 2012; Lang, 2000).

Spawning

In New Zealand spawning occurs around multiple places throughout both the North and South Islands along shallow and mid-shelf coastal waters (NIWA, 2012). Spawning time ranges all the way from spring to autumn – September to May – and ovulating females have been reported all year round (Clearwater & Pankhurst, 1994), but peak spawning time is in late spring and early summer – November and December (Rainer & Reyes, 2019; Roberts, et al., 2015). The end of the spawning season coincides with decreasing day length and increasing temperature, which are possibly used as regulatory indicators. The eggs and the larvae growth are in surface waters (Ministry for Primary Industries, 2008). They can accidentally be caught in shallow sea ports, in this way some juveniles can be seen in these areas (Lang, 2000).

Diet and foraging

The red gurnard is an opportunistic feeder, preying principally on crustaceans but pretty much any small macrofauna such as shrimp/prawns, crabs, crayfish, lobster, amphipods, small fish, and polychaete worms (Eichelsheim, 2010; Furukawa & Ikeda, 1953; Rainer & Reyes, 2019; Lang, 2000; Roberts, et al., 2015). It uses modified fin rays under its pectorals to probe the sand for prey and may also use the large fan-like pectoral fins to offer prey mock shelter. They can be found in shallow water with soft ground after being stirred by winter storms and around the seasonal migrations of small shoreline fish like whitebait, anchovy, and pilchard. (Eichelcheim, 2010).

Along the Australian shores, the red gurnard seems to be one of the apex predators with dogfishes, dories, lings and other flatheads (Bulman, et al., 2001).

A possible use for its large pectoral fins may be to make it appear larger to scare off potential predators (Eichelsheim, 2010).

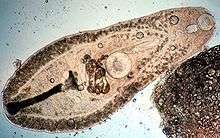

Predators, Parasites, and Diseases

.jpg)

The red gurnard's predators are not well-known. This fish has been found to have been included in the stomach contents of fur seals in Bank's Peninsula, but does not represent an entire diet (DoC, 2009; Allum & Maddigan, 2012).

Some parasites can be found in the red gurnard. Nematoda larvae can infect this fish such as Anisakis or Contracaecum larvae which can be found in viscera, intestines, or other body cavities (Hewitt & Hine, 1972; Lymbery, et al., 2002). According to Hewitt and Hine (1972), the parasites found in the red gurnard can be summarized into two different groups: Digenea and Nematoda.

| Group | Species | Location in the red gurnard |

| DIGENEA | Stephanostomum australis | intestine |

| Plagioporus preporatus | intestine | |

| Helicometra grandora | intestine | |

| Tubulovesiculu angusticauda | stomach | |

| Derogenes various | stomach | |

| NEMATODA | Anisakis sp. larva | viscera, mesenteries, under peritoneum |

| Contracaecum sp. larva | two types, in stomach, intestine and body cavity | |

| Ascarophis sp. | stomach | |

| Capillaria sp. | stomach |

Commercial Fisheries

The red gurnard is an important commercial fish in areas like Hawks Bay and Golden Bay via bottom-trawling or bottom long-lining, and also a regular catch of recreational fishers from boats and surf catching (Eichelsheim, 2010). The National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) includes red gurnard in a list of key inshore species to be trawl-surveyed every two years for the Ministry of Primary Fisheries (MPI) to assess populations and aid in informing fishery management. NIWA also holds interviews at recreational fishing ramps along Shelly Beach and the 20 busiest boat ramps along the North Island's northeast coast to gather information for further insight into population sizes and health, asking questions such as where fish had been caught, how big they were, and what bait had been used (MacGibbon & Hurst, 2017). The legal fishing size is 25 cm.

The red gurnard is a popular food fish (Lang, 2000). About 4000 tons are catch annually in New Zealand (Ayling & Cox, 1982), it was one of the most important species, placed at the 4th position in term of quantity in the early 70s (Lang, 2000). Even if their number was low in the mid-1990s in New-Zealand, the population has increased and seems to stay constant (Ministry for Primary Industries, 2018). It has a very good, pink and firm flesh with a low rate of fat (Lang, 2000).

Vocalizations

These fish are known to be quite vocal when captured, emitting loud grunts (Eichelsheim, 2010). Although referred to as “vocalization”, sounds are not actually made through laryngeal mechanics but are thought to be produced by contracting pairs of intrinsic sonic muscles in the swim bladder. The growling sound is a nocturnal vocalization emitted at night and singly, whereas the grunts is produced when the animals are grouped. Grunts sounds last 0.2 seconds and can be heard without any advice, their frequency range are from 250 to 300 Hz (Clara & Amorim, 2006).

Radford et al. (2016) conducted a study of a captive female red gurnard and discovered four separate types of sound it can produce in two separate aural categories: grunt and growl. Its vocalizations were heard every hour around the clock with increases at dawn and dusk, and growls were made at night. The sounds were not found to be associated with feeding activity and in this setting were unlikely to be distress. The vocalizations may indicate associations with reproductive state as they are known to make the most noise during breeding season and generally are “likely to be significant contributors to [the] ambient underwater soundscape.”

References

- Allum L.L., Maddigan F.W. (2012). Unusual stability of diet of the New Zealand fur seal (Arctocephalus forsteri) at Banks Peninsula, New Zealand Journal of Marine Freshwater Research, 46:1, 91-96

- Ayling T., Cox G.J. (1982). Collins guide to the sea fishes of New Zealand. Collins, p. 197, 322 pp.

- Bulman C., Althaus F., He X., Bax N.J., Williams A. (2001). Diets and trophic guilds of demersal fishes of the south-eastern Australian shelf, CSIRO Marine Freshwater Research,52, 537–48

- Clara M., Amorim P. (2006). Diversty of sound production in fish, Sound Communication in Fishes, Springer, 3, 71-105

- Clearwater, S.J. & Pankhurst, N.W. (1994). Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology of Female Red Gurnard, Chelidonichthys kumu (Lesson and Garnot) (Family Triglidae), from the Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand. Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 45(2):131-139.

- Department of Conservation (DoC). (2009). It’s good news for seals and it’s good news for fishers. Retrieved from https://www.doc.govt.nz/news/media-releases/2009/its-good-news-for-seals-and-its-good-news-for-fishers/

- Eichelsheim, J. (2010). Top Catch: Hook up New Zealand’s top 12 species. Auckland, New Zealand: Random House New Zealand.

- Elder, R. D. (1976). Studies on age, growth, reproduction and population dynamics of red gurnard, Chelidonichthys kumu, in the Hauraki Gulf. New Zealand Fisheries Research Bulletin 12, 1–77.

- FAO Fisheries Department. (1981). Atlas of the Living Resources of the Seas. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Fishbase (2009), Chelidonichthys kumu, retrieved 13/03/2019 from https://www.fishbase.se/summary/507

- Francis M. (2012). Coastal fishes of New Zealand – Identification – Biology – Behavior. Nelson: Craig Potton Publishing, p. 82, 268 pp.

- Furukawa, I. & Ikeda, M. (1953). Ecological studies on the bottom fish in the Hyuga Nada – I. Red Gurnard. Bulletin of the Japanese Society of Scientific Fisheries, 19:390-7.

- Hewitt G. C. & Hine P. M. (1972). Checklist of parasites of New Zealand fishes and of their hosts, New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 6:1-2, 69-114. International Union for Conservation of Nature (2010), Bluefin Gurnard, retrieved 13/03/2019 from https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/154895/4661163

- Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). (2019). Chelidonichthys kumu (Cuvier 1829). Retrieved from https://itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=167052#null

- Lang P. (2000). New Zealand fishes – Identification, natural history and fisheries. Reed, p. 80-81, 253 pp.

- Lymbery A. J., Doupé R.G., Munshi M. A., Wong T. (2002). Larvae of Contracaecum sp. among inshore fish species of southwestern Australia. Diseases of Aquatic Organism, 51, 157-159.

- Lyon, W.S. & Horn, P.L. (2011) Length and age of red gurnard (Chelidonichthys kumu) from trawl surveys off west coast South Island in 2003, 2005, and 2007, with comparisons to earlier surveys in the time series. New Zealand Fisheries Assessment Report 2011/46.

- MacGibbon, D. & Hurst, R. (2017) NIWA research vessel surveying fish in Tasman and Golden Bays. Retrieved from https://niwa.co.nz/news/niwa-research-vessel-surveying-fish-in-tasman-and-golden-bays

- Ministry for Primary Industries (2008), Red Gurnard (GUR), retrieved 16/03/2019 from https://fs.fish.govt.nz/Doc/5463/GUR_FINAL%2008.pdf.ashx

- Ministry for Primary Industries (2018), Red Gurnard, retrieved 16/03/2019 from https://www.mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/29714-review-of-sustainability-measures-for-2018-part11-red-gurnard-gur-3/loggedin

- Powell A.W.B. (1947). Powell’s Native Animals of New Zealand (4th Edition). Auckland: David Bateman Ltd, p. 71, 94 pp.

- Radford C.A., Ghazali S.M., Montgomery J.C., Jeffs A.G. (2016). Vocalization Repertoire of Female Bluefin Gurnard (Chelidonichthys kumu) in Captivity: Sound Structure, Context and Vocal Activity. PLOS ONE, 15 pp.

- Rainer, F. & Reyes, RB. (2019). Chelidonichthys kumu (Cuvier 1829). Retrieved from https://www.fishbase.de/summary/Chelidonichthys-kumu.html

- Roberts D.C., Stewart A.L., Struthers C.D. (2015). The fishes of New-Zealand (Volume 3)-Systematic Accounts. Te Papa Press, p. 1108, 575 pp.

- Tony Ayling & Geoffrey Cox. Collins Guide to the Sea Fishes of New Zealand. William Collins Publishers Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand. 1982. ISBN 0-00-216987-8

- World Register of Marine Species (2008), Chelidonichthys kumu (Cuvier, 1829), retrieved 13/03/2019 from http://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=218122

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chelidonichthys kumu. |