Blood Meridian

Blood Meridian or The Evening Redness in the West is a 1985 epic Western, although some refer to it as an anti-Western,[1][2] novel by American author Cormac McCarthy. McCarthy's fifth book, it was published by Random House. It is loosely based on historical events.

First edition cover | |

| Author | Cormac McCarthy |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Western, historical novel |

| Publisher | Random House |

Publication date | April 1985 |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 337 (first edition, hardback) |

| ISBN | 0-394-54482-X (first edition, hardback) |

| OCLC | 234287599 |

| 813/.54 19 | |

| LC Class | PS3563.C337 B4 1985 |

The majority of the story follows a teenager referred to only as "the kid," with the bulk of the text devoted to his experiences with the Glanton gang, a historical group of scalp hunters who massacred Native Americans and others in the United States–Mexico borderlands from 1849 to 1850 for bounty, pleasure, and eventually out of nihilistic habit. The role of antagonist is gradually filled by Judge Holden, a physically massive, highly educated, preternaturally skilled member of the gang who is depicted as completely bald from head to toe.

Although the novel initially received lukewarm critical and commercial reception, it has since become highly acclaimed and is widely recognized as McCarthy's magnum opus, as well as one of the greatest American novels of all time.[3] Some have even labelled it the Great American Novel.[4] As a result, there have been multiple attempts to adapt the novel into a film, but none have succeeded.

Plot summary

Three epigraphs open the book: quotes from French writer Paul Valéry, from German Christian mystic Jacob Boehme, and a 1982 news clipping from the Yuma Sun reporting the claim of the members of an Ethiopian archeological or anthropological expedition that a 300,000 year-old human skull had been scalped.

The novel tells the story of a teenage runaway named only as "the kid", who was born in Tennessee during the famously active Leonids meteor shower of 1833. He first meets the enormous and hairless Judge Holden at a religious revival in a tent in Nacogdoches, Texas: Holden falsely accuses the preacher of pedophilia and bestiality, inciting the audience to attack him.

After a violent encounter with a bartender establishes the kid as a formidable fighter, he joins a party of ill-equipped U.S. Army irregulars on a filibustering mission led by a Captain White. Failing to stay clear of a huge herd of rustled and stolen animals, White's group is overwhelmed by an accompanying group of hundreds of Comanche warriors. Few of them survive. Arrested as a filibuster in Chihuahua, the kid is set free when his acquaintance Toadvine tells the authorities they will make useful Indian hunters for the state's newly hired scalphunting operation. They join Glanton and his gang, and the bulk of the novel is devoted to detailing their activities and conversations. The gang encounters a traveling carnival, and, in untranslated Spanish, several of their fortunes are told with Tarot cards. The gang originally contract with various regional leaders to protect locals from marauding Apaches, and are given a bounty for each scalp they recover. Before long, however, they devolve into the outright murder of unthreatening Indians, unprotected Mexican villages, and eventually even the Mexican army and anyone else who crosses their path.

Throughout the novel Holden is presented as a profoundly mysterious and awe-inspiring figure; the others seem to regard him as not quite human. Like the historical Holden of Chamberlain's autobiography, he is a child-killer. According to the kid's new companion Ben Tobin, an "ex-priest", the Glanton gang first met the judge while fleeing for their lives from a much larger Apache group. In the middle of a blasted desert, they found Holden sitting on an enormous boulder, where he seemed to be waiting for the gang. In a scene with distinctly Faustian overtones,[5] they agreed to follow his leadership, and he took them to an extinct volcano, where, astoundingly, he instructed the ragged, desperate gang on how to manufacture gunpowder, enough to give them the advantage against the Apaches. When the kid remembers seeing Holden in Nacogdoches, Tobin tells the kid that each man in the gang claims to have met the judge before he joined the Glanton Gang.

After months of marauding, the gang crosses into U.S. territory, where they eventually set up a systematic and brutal robbing operation at a ferry on the Gila River at Yuma, Arizona. Local Yuma (Quechan) Indians are at first approached to help the gang wrest control of the ferry from its original owners, but Glanton's gang betrays them, using their presence and previously coordinated attack on the ferry as an excuse to seize the ferry's munitions and slaughter the Yuma. Because of the new operators' brutal ways, the U.S. Army and the Yumas set up a second ferry at a ford upriver. After a while, the Yumas attack and kill most of the gang. The kid, Toadvine and Tobin are among the survivors who flee into the desert, though the kid takes an arrow in the leg. The kid and Tobin head west, and come across Holden, who first negotiates, then threatens them for their gun and possessions. Holden shoots Tobin in the neck, and the wounded pair hide among bones by a desert creek. Tobin repeatedly urges the kid to fire upon Holden. The kid does so – only once – but misses his mark.

The survivors continue their travels, ending up in San Diego. The kid gets separated from Tobin and is subsequently imprisoned. Holden visits the kid in jail, and tells him that he has told the jailers "the truth": that the kid alone was responsible for the end of the Glanton gang. The kid declares that the judge was responsible for the gang's evil, but the judge denies it. The kid stoically rebuts all of Holden's statements, but when the judge reaches through the cell bars to touch him, the kid recoils in disgust. Holden leaves the kid in jail, stating that he "has errands." The kid is released on recognizance and seeks a doctor to treat his wound. While recovering from the "spirits of ether", he hallucinates the judge visiting him along with a curious man who forges coins. The kid recovers and seeks out Tobin, with no luck. He makes his way to Los Angeles, where Toadvine and another member of the Glanton gang, David Brown, are hanged for their crimes.

The kid again wanders across the American West, and decades are compressed into a few pages. In 1878 he makes his way to Fort Griffin, Texas. The lawless city is a center for processing the remains of the American Bison, which have been hunted nearly to extinction. At a saloon he meets the judge. Holden calls the kid "the last of the true," and the pair talk. Holden describes the kid as a disappointment, stating that he held in his heart "clemency for the heathen." Holden declares that the kid has arrived at the saloon for "the dance" – the dance of violence, war, and bloodshed that the judge had so often praised. The kid seems to deny all of these ideas, telling the judge "You aint nothin [sic]," and noting the performing bear at the saloon, states, "even a dumb animal can dance."

The kid hires a prostitute, then afterwards goes to an outhouse under another meteor shower. In the outhouse, he is surprised by the naked judge, who "gathered him in his arms against his immense and terrible flesh." This is the last mention of the kid, though in the next scene two men come from the saloon and encounter a third man (possibly Holden, though it is not stated) urinating near the outhouse. The unnamed third man advises the two not to go in the outhouse. They ignore the suggestion, open the door, and can only gaze in awed horror at what they see, one of them stating "Good God almighty." The last paragraph finds the judge back in the saloon, dancing and playing fiddle among the drunkards and the whores, saying that he will never die.

The ambiguous fate of the kid is followed by an epilogue, featuring a possibly allegorical man augering lines of holes across the prairie, perhaps for fence posts. The man sparks a fire in each of the holes, and an assortment of wanderers trail behind him.

Characters

Major characters

- The kid: The novel's anti-heroic protagonist or pseudo-protagonist,[6] the kid is a Tennessean initially in his mid-teens whose mother died in childbirth and who flees from his father to Texas. He is said to have a disposition for bloodshed and is involved in many vicious actions early on; he takes up inherently violent professions, specifically being recruited by murderers including Captain White, and later, by Glanton and his gang, to secure release from a prison in Chihuahua, Mexico. The kid takes part in many of the Glanton gang's scalp-hunting rampages, but gradually displays a moral fiber that ultimately puts him at odds with the Judge. "The kid" is later, as an adult, referred to as "the man", when he encounters the judge again after nearly three decades.

- Judge Holden, or "the judge": An enormous, pale, and hairless man, who often seems almost mythical or supernatural. Possessing peerless knowledge and talent in everything from dance to legal argument, Holden is a dedicated examiner and recorder of the natural world and a supremely violent and perverted character. He rides with (though largely does not interact with) Glanton's gang after they find him sitting on a rock in the middle of the desert and he saves them from an Apache attack using his exceptional intellect, skill, and nearly superhuman strength. It is hinted at that he and Glanton have forged some manner of a pact, possibly for the very lives of the gang members. He gradually becomes the antagonist to the kid after the dissolution of Glanton's gang, occasionally having brief reunions with the kid to mock, debate, or terrorize him. Unlike the rest of the gang, Holden is socially refined and remarkably well educated; however, he perceives the world as ultimately violent, fatalistic, and liable to an endless cycle of bloody conquest, with human nature and autonomy defined by the will to violence; he asserts, ultimately, that "War is god."

- Louis Toadvine: A seasoned outlaw the kid originally encounters in a vicious brawl and who then burns down a hotel, Toadvine is distinguished by his head which has no ears and his forehead branded with the letters H, T, (standing for "horse thief") and F. He later reappears unexpectedly as a cellmate of the kid in the Chihuahua prison. Here, he somewhat befriends the kid, negotiating his and the kid's release in return for joining Glanton's gang, to whom he claims dishonestly that he and the kid are experienced scalp hunters. Toadvine is not as depraved as the rest of the gang and opposes the judge's methods ineffectually, but is still a violent individual himself. He is hanged in Los Angeles alongside David Brown.

- Tobin, "the priest", or "the ex-priest": A former novice of the Society of Jesus, Tobin instead turns to a life of crime in Glanton's gang, though remains deeply religious. He feels an apparently friend-like bond with the kid and abhors the judge and his philosophy; he and the judge gradually become great spiritual enemies. Although he survives the Yuma massacre of Glanton's gang, during his escape in the desert he is shot in the neck by the judge and seeks medical attention in San Diego. His ultimate fate, however, remains unknown.

Other recurring characters

- Captain White, or "the captain": An ex-professional soldier and American supremacist who believes that Mexico is a lawless nation destined to be conquered by the United States, Captain White leads a ragtag group of militants into Mexico. The kid joins Captain White's escapades before his capture and imprisonment; he later discovers that White has been decapitated by his enemies.

- John Joel Glanton, or simply Glanton: Glanton is the American leader (sometimes deemed "captain") of a band of scalphunters who murder Indians as well as Mexican civilians and militants alike. His history and appearance are not clarified, except that he is physically small with black hair and has a wife and child in Texas though he has been banned from returning there because of his criminal record. A clever strategist, his last major action is to seize control of a profitable Colorado River ferry, which leads him and most of his gang to be killed in an ambush by Yuma Indians.

- David Brown: An especially radical member of the Glanton band, David Brown becomes known for his dramatic displays of violence. He wears a necklace of human ears (similar to the one worn by Bathcat before his immolation). He is arrested in San Diego and sought out by Glanton personally, who seems especially concerned to see him freed (though Brown ends up securing his own release). Though he survives the Yuma massacre, he is captured with Toadvine in Los Angeles and both are hanged.

- John Jackson: "John Jackson" is a name shared by two men in Glanton's gang— one black, one white— who detest one another and whose tensions frequently rise when in each other's presence. After trying to drive the black Jackson away from a campfire with a racist remark, the white one is decapitated by the black one; the black Jackson later becomes the first person killed in the Yuma massacre.

Themes

Violence

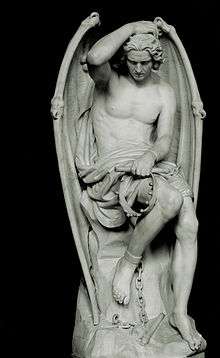

The Old Hermit, pg. 19

A major theme is the warlike nature of man. A show of violence early in the novel consists of the protagonist getting clubbed in the head.[7] Critic Harold Bloom[8] praised Blood Meridian as one of the best 20th century American novels, describing it as "worthy of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick,"[9] but admitted that he found the book's pervasive violence so shocking that he had several false starts before reading the book entirely. Caryn James argued that the novel's violence was a "slap in the face" to modern readers cut off from the brutality of life, while Terrence Morgan thought that, though initially shocking, the effect of the violence gradually waned until the reader was bored.[10] Billy J. Stratton contends that the brutality depicted is the primary mechanism through which McCarthy challenges binaries and promotes his revisionist agenda.[11] Lilley argues that many critics struggle with the fact that McCarthy does not use violence for "jury-rigged, symbolic plot resolutions . . . In McCarthy's work, violence tends to be just that; it is not a sign or symbol of something else."[12] Others have noted that McCarthy depicts characters of all backgrounds as evil, in contrast to contemporary "revisionist theories that make white men the villains and Indians the victims."[13]

Epigraphs and ending

Three epigraphs open the book: quotations from French writer Paul Valéry, from German Christian mystic Jacob Boehme, and a 1982 news clipping from the Yuma Sun reporting the claim of members of an Ethiopian archeological excavation that a fossilized skull three hundred millennia old seemed to have been scalped. The themes implied by the epigraphs have been variously discussed without specific conclusions.

As noted above concerning the ending, the most common interpretation of the novel is that Holden kills the kid in a Fort Griffin, Texas, outhouse. The fact that the kid's death is not depicted might be significant. Blood Meridian is a catalog of brutality, depicting, in sometimes explicit detail, all manner of violence, bloodshed, brutality and cruelty. For the dramatic climax to be left undepicted leaves something of a vacuum for the reader: knowing full well the horrors established in the past hundreds of pages, the kid's unstated fate might still be too awful to describe, and too much for the mind to fathom: the sight of the kid's fate leaves several witnesses stunned almost to silence; never in the book does any other character have this response to violence, again underlining the singularity of the kid's fate.

Patrick W. Shaw argues that Holden has sexually violated the protagonist. As Shaw writes, the novel had several times earlier established "a sequence of events that gives us ample information to visualize how Holden molests a child, then silences him with aggression."[14] According to Shaw's argument, Holden's actions in the Fort Griffin outhouse are the culmination of what he desired decades earlier: to rape the kid, then perhaps kill him to silence the only survivor of the Glanton gang. If the judge wanted only to kill the kid, there would be no need for him to undress as he waited in the outhouse. Shaw writes,

When the judge assaults the kid in the Fort Griffin jakes… he betrays a complex of psychological, historical and sexual values of which the kid has no conscious awareness, but which are distinctly conveyed to the reader. Ultimately, it is the kid's personal humiliation which impacts the reader most tellingly. In the virile warrior culture which dominates that text and to which the reader has become acclimated, seduction into public homoeroticism is a dreadful fate. We do not see behind the outhouse door to know the details of the kid's corruption. It may be as simple as the embrace that we do witness or as violent as the sodomy implied by the judge's killing of the Indian children. The kid's powerful survival instinct perhaps suggests that he is a more willing participant than a victim. However, the degree of debasement and the extent of the kid's willingness are incidental. The public revelation of the act is what matters. Other men have observed the kid's humiliation… In such a male culture, public homoeroticism is untenable and it is this sudden revelation that horrifies the observers at Fort Griffin. No other act could offend their masculine sensibilities as the shock they display… This triumph over the kid is what the exhibitionist and homoerotic judge celebrates by dancing naked atop the wall, just as he did after assaulting the half-breed boy.

— Patrick W. Shaw, "The Kid's Fate, the Judge's Guilt"[15]

Yet Shaw’s effort to penetrate the mystery in the jakes has not managed to satisfy other critics, who have rejected his thesis as more sensational than textual:

Patrick W. Shaw's article . . . reviews the controversy over the end of McCarthy's masterpiece: does the judge kill the kid in the 'jakes' or does he merely sexually assault him? Shaw then goes on to review Eric Fromm's distinction between benign and malignant aggression – benign aggression being only used for survival and is rooted in human instinct, whereas malignant aggression is destructive and is based in human character. It is Shaw's thesis that McCarthy fully accepts and exemplifies Fromm's malignant aggression, which he sees as part of the human condition, and which we do well to heed, for without this acceptation we risk losing ourselves in intellectual and physical servitude. Shaw goes in for a certain amount of special pleading: the Comanches sodomizing their dying victims; the kid's exceptional aggression and ability, so that the judge could not have killed him that easily; the judge deriving more satisfaction from tormenting than from eliminating. Since the judge considers the kid has reserved some clemency in his soul, Shaw argues, that the only logical step is that the judge humiliates him by sodomy. This is possible, but unlikely. The judge gives one the impression, not so much of male potency, but of impotence. His mountainous, hairless flesh is more that of a eunuch than a man. Having suggested paedophilia, Shaw then goes back to read other episodes in terms of the judge's paedophilia: the hypothesis thus becomes the premise. And in so arguing, Shaw falls into the same trap of narrative closure for which he has been berating other critics. The point about Blood Meridian is that we do not know and we cannot know.

— Peter J. Kitson (Ed.), "The Year's Work in English Studies Volume 78 (1997)"[16]

Religion

Hell

David Vann argues that the setting of the American southwest which the Gang traverses is representative of hell. Vann claims that the Judge's kicking of a head is an allusion to Dante's similar action in the Inferno.[17]

Gnosticism

Various discussions by Leo Daugherty, Barclay Owens, Harold Bloom and others, have resulted from the second epigraph of the three which are used by the author to introduce the novel taken from the "Gnostic" mystic Jacob Boehme. The quote from Boehme reads as follows: "It is not to be thought that the life of darkness is sunk in misery and lost as if in sorrowing. There is no sorrowing. For sorrow is a thing that is swallowed up in death, and death and dying are the very life of the darkness."[18] No specific conclusions have been reached concerning its interpretation and the extent of its direct or indirect relevance to the novel.

These critics agree that there are Gnostic elements present in Blood Meridian, but they disagree on the precise meaning and implication of those elements. One of the most detailed of these arguments is made by Leo Daugherty in his 1992 article, "Blood Meridian as Gnostic Tragedy." Daugherty argues "Gnostic thought is central to Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian" (Daugherty, 122); specifically, the Persian-Zoroastrian-Manichean branch of Gnosticism. He describes the novel as a "rare coupling of Gnostic 'ideology' with the 'affect' of Hellenic tragedy by means of depicting how power works in the making and erasing of culture, and of what the human condition amounts to when a person opposes that power and thence gets introduced to fate."[19]

Daugherty sees Holden as an archon, and the kid as a "failed pneuma." Daugherty makes the interpretive claim that the kid feels a "spark of the alien divine."[20] Furthermore, the kid rarely initiates violence, usually doing so only when urged by others or in self-defense. Holden, however, speaks of his desire to dominate the earth and all who dwell on it, by any means: from outright violence to deception and trickery. He expresses his wish to become a "suzerain," one who "rules even when there are other rulers" and whose power overrides all others'. In 2009, Bloom did refer to Boehme in the context of Blood Meridian as, "a very specific type of Kabbalistic Gnostic".

Daugherty contends that the staggering violence of the novel can best be understood through a Gnostic lens. "Evil" as defined by the Gnostics was a far larger, more pervasive presence in human life than the rather tame and "domesticated" Satan of Christianity. As Daugherty writes, "For [Gnostics], evil was simply everything that is, with the exception of bits of spirit imprisoned here. And what they saw is what we see in the world of Blood Meridian."[21] Barcley Owens argues that, while there are undoubtedly Gnostic qualities to the novel, Daugherty's arguments are "ultimately unsuccessful,"[22] because Daugherty fails to address the novel's pervasive violence adequately and because he overstates the kid's goodness.

Theodicy

Another major theme concerning Blood Meridian involves the subject of theodicy. Theodicy in general refers to the issue of the philosophical or theological attempt to justify the existence of that which is metaphysically or philosophically good in a world which contains so much apparent and manifest evil. Douglas Canfield in his essay "Theodicy in Blood Meridian" (in his book Mavericks on the Border, 2001, Lexington University Press)[23] asserts that theodicy is the central theme of Blood Meridian. James Wood in his essay for The New Yorker entitled "Red Planet" from 2005 took a similar position to this in recognizing the issue of the general justification of metaphysical goodness in the presence of evil in the world as a recurrent theme in the novel.[24] This was directly supported by Edwin Turner on 28 September 2010 in his essay on Blood Meridian for Biblioklept.[25] Chris Dacus in the Cormac McCarthy Journal for 2009 wrote the essay entitled, "The West as Symbol of the Eschaton in Cormac McCarthy," where he expressed his preference for discussing the theme of theodicy in its eschatological terms in comparison to the theological scene of the last judgment. This preference for reading theodicy as an eschatological theme was further affirmed by Harold Bloom in his recurrent phrase of referring to the novel as "The Authentic Apocalyptic Novel."[26]

Background

.jpg)

McCarthy first began writing Blood Meridian in 1975, as he finished Suttree. Blood Meridian was his first attempt at a western.[27] He expanded Blood Meridian while living on the money from his 1981 MacArthur Fellows grant. It is his first novel set in the Southwestern United States, a change from the Appalachian settings of his earlier work. In his essay for the Slate Book Review from 5 October 2012 entitled "Cormac McCarthy Cuts to the Bone", Noah Shannon summarizes the existing library archives of the first drafts of the novel as dating to the mid-1970s. The review includes digital archive images of several of McCarthy's own type-script pages for early versions of the novel.[28] The character of Judge Holden was first added to the manuscript in the late 1970s, partially inspired by John Milton's Satan and Kurtz of Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness.[29]

McCarthy conducted considerable research to write the book. He followed the Glanton Gang's trail through Mexico multiple times, noting topography and fauna.[30] Critics have repeatedly demonstrated that even brief and seemingly inconsequential passages of Blood Meridian rely on historical evidence. The Glanton gang segments are based on Samuel Chamberlain's account of the group in his memoir My Confession: The Recollections of a Rogue, which he wrote during the latter part of his life. Chamberlain rode with John Joel Glanton and his company between 1849 and 1850. The novel's antagonist Judge Holden appeared in Chamberlain's account, but his true identity remains a mystery. In Samuel Chamberlain's autobiographical My Confession, he described Holden as:

"The second in command, now left in charge of the camp, was a man of gigantic size who rejoiced in the name of Holden, called Judge Holden of Texas. Who or what he was no one knew, but a cooler-more blooded villain never went unhung. He stood six foot six in his moccasins, had a large, fleshy frame, a dull, tallow-colored face destitute of hair and all expression, always cool and collected. But when a quarrel took place and blood shed, his hog-like eyes would gleam with a sullen ferocity worthy of the countenance of a fiend… Terrible stories were circulated in camp of horrid crimes committed by him when bearing another name in the Cherokee nation in Texas. And before we left Fronteras, a little girl of ten years was found in the chaparral foully violated and murdered. The mark of a huge hand on her little throat pointed out him as the ravisher as no other man had such a hand. But though all suspected, no one charged him with the crime. He was by far the best educated man in northern Mexico."[31]

Chamberlain does not appear in the novel. He studied such topics as homemade gunpowder to accurately depict the Judge's creation from volcanic rock. In 1974 McCarthy moved from his native Tennessee to El Paso, Texas to immerse himself in the culture and geography of the American Southwest. In El Paso, he taught himself the Spanish, which many of the characters of Blood Meridian speak.[32]

Style

McCarthy told Oprah Winfrey in an interview that he prefers "simple declarative sentences" and that he uses capital letters, periods, an occasional comma, a colon for setting off a list, but never semicolons.[33] He does not use quotation marks for dialogue and believes there is no reason to "blot the page up with weird little marks".[34] His prose was described as "Faulknerian."[35] Describing events of extreme violence, McCarthy's prose is sparse, yet expansive, with an often biblical quality and frequent religious references. McCarthy's writing style involves many unusual or archaic words, no quotation marks for dialogue, and no apostrophes to signal most contractions.

Reception and reevalution

While Blood Meridian initially received little recognition, it has since been recognized as McCarthy's masterpiece, and one of the greatest works of American literature. American literary critic Harold Bloom praised Blood Meridian as one of the 20th century's finest novels.[36] Time magazine included the novel in its "TIME 100 Best English-language Novels from 1923 to 2005".[37] Some have gone so far as to label it the Great American Novel.[38]

Aleksandar Hemon has called Blood Meridian "possibly the greatest American novel of the past 25 years." In 2006, The New York Times conducted a poll of writers and critics regarding the most important works in American fiction from the previous 25 years; Blood Meridian was a runner-up, along with John Updike's four novels about Rabbit Angstrom and Don DeLillo's Underworld while Toni Morrison's Beloved topped the list.[39] Novelist David Foster Wallace named Blood Meridian one of the five most underappreciated American novels since 1960[40] and described it as "[p]robably the most horrifying book of this century, at least [in] fiction."[41]

Literary significance

Academics and critics have variously suggested that Blood Meridian is nihilistic or strongly moral; a satire of the western genre, a savage indictment of Manifest Destiny. Harold Bloom called it "the ultimate western"; J. Douglas Canfield described it as "a grotesque Bildungsroman in which we are denied access to the protagonist's consciousness almost entirely."[42] Comparisons have been made to the work of Hieronymus Bosch and Sam Peckinpah, and of Dante Alighieri and Louis L'Amour. However, there is no consensus interpretation; James D. Lilley writes that the work "seems designed to elude interpretation."[12] After reading Blood Meridian, Richard Selzer declared that McCarthy "is a genius--also probably somewhat insane."[43] Critic Steven Shaviro wrote:

In the entire range of American literature, only Moby-Dick bears comparison to Blood Meridian. Both are epic in scope, cosmically resonant, obsessed with open space and with language, exploring vast uncharted distances with a fanatically patient minuteness. Both manifest a sublime visionary power that is matched only by still more ferocious irony. Both savagely explode the American dream of manifest destiny [sic] of racial domination and endless imperial expansion. But if anything, McCarthy writes with a yet more terrible clarity than does Melville.

— Steven Shaviro, "A Reading of Blood Meridian"[44]

Attempted film adaptations

.jpg)

From the novel's release, many have noted its cinematic potential. The New York Time's 1985 review noted that the novel depicted "scenes that might have come off a movie screen."[45] As a result, there have been a number of attempts to create a motion picture adaptation of Blood Meridian. However, all have failed during the development or pre-production stages. A common perception is that the story is "unfilmable", due to its unrelenting violence and dark tone. In an interview with Cormac McCarthy by The Wall Street Journal in 2009, McCarthy denied this notion, with his perspective being that it would be "very difficult to do and would require someone with a bountiful imagination and a lot of balls. But the payoff could be extraordinary."[46]

Screenwriter Steve Tesich first adapted Blood Meridian into a screenplay in 1995. In the late 1990s, Tommy Lee Jones acquired the film adaptation rights to the story and subsequently rewrote Tesich's screenplay, with the idea of directing and playing a role in it.[47] Due to film studios avoiding the project's overall violence, production could not move forward. [48]

Following the end of production for Kingdom of Heaven in 2004, screenwriter William Monahan and director Ridley Scott entered discussions with producer Scott Rudin for adapting Blood Meridian with Paramount Pictures financing.[49] In a 2008 interview with Eclipse Magazine, Scott confirmed that the screenplay had been written, but that the extensive violence was proving to be a challenge for film standards.[50] This later led to Scott and Monahan leaving the project, resulting in another abandoned adaptation.[51]

By early 2011, James Franco was thinking of adapting Blood Meridian, along with a number of other William Faulkner and Cormac McCarthy novels.[52] After being persuaded by Andrew Dominik to adapt the novel, Franco shot twenty-five minutes of test footage, starring Scott Glenn, Mark Pellegrino, Luke Perry, and Dave Franco. For undisclosed reasons, Rudin denied further production of the film.[48] On May 5, 2016, Variety revealed that Franco was negotiating with Rudin to write and direct an adaptation to be brought to the Marché du Film, with Russell Crowe, Tye Sheridan, and Vincent D'Onofrio starring. However, later that day, it was reported that the project dissolved, due to issues concerning the film rights.[53]

Notes

References

- Kollin, Susan (2001). "Genre and the Geographies of Violence: Cormac McCarthy and the Contemporary Western". Contemporary Literature. University of Wisconsin Press. 42 (3): 557–88. doi:10.2307/1208996. JSTOR 1208996.

- Hage, Erik. Cormac McCarthy: A Literary Companion. North Carolina: 2010. p. 45

- "Harold Bloom on Blood Meridian".

- Dalrymple, William. "Blood Meridian is the Great American Novel". Reader's Digest.

McCarthy’s descriptive powers make him the best prose stylist working today, and this book the Great American Novel.

- Crews, Michael Lynn (September 5, 2017). Books Are Made Out of Books: A Guide to Cormac McCarthy's Literary Influences. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. p. 131–132. ISBN 9781477314708.

- https://slate.com/culture/2012/10/cormac-mccarthys-blood-meridian-early-drafts-and-history.html

- p. 9

- Bloom, Harold, How to Read and Why. New York: 2001.

- Bloom, Harold, "Dumbing down American readers." Boston Globe, op-ed, September 24, 2003.

- Owens, p. 7.

- Stratton, Billy J. (2011). "'el brujo es un coyote': Taxonomies of Trauma in Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian". Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory. 67 (3): 151–172. doi:10.1353/arq.2011.0020.

- Lilley, p. 19.

- https://www.nytimes.com/1985/04/28/books/blood-meridian-by-cormac-mccarthy.html

- Shaw, p. 109.

- Shaw, p. 117–118.

- Kitson, p. 809.

- Vann, David (November 13, 2009). "American inferno". The Guardian. London. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Mundik, Petra (May 15, 2016). A Bloody and Barbarous God: The Metaphysics of Cormac McCarthy. University of New Mexico Press. p. 32. ISBN 9780826356710. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- Daugherty, p. 129.

- Daugherty, Leo. “Gravers False and True: Blood Meridian as Gnostic Tragedy.” Perspectives on Cormac McCarthy. Ed. Edwin T. Arnold and Dianne C. Luce. University Press of Mississippi: Jackson, 1993. 157-172

- Daugherty, p. 124; emphasis in original.

- Owens, p. 12.

- Canfield, J. D. (2001). Mavericks on the Border. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-813-12672-2.

- Wood, James (July 25, 2005). "Red Planet: The sanguinary sublime of Cormac McCarthy". The New Yorker. New York. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- Turner, Edwin (September 27, 2010). "Blood Meridian". Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- "Interview with Harold Bloom". November 28, 2000. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- https://slate.com/culture/2012/10/cormac-mccarthys-blood-meridian-early-drafts-and-history.html

- Shannon, Noah (2012-10-05). "Cormac McCarthy Cuts to the Bone". Slate Book Review, 5 October 2012.

- https://slate.com/culture/2012/10/cormac-mccarthys-blood-meridian-early-drafts-and-history.html

- https://slate.com/culture/2012/10/cormac-mccarthys-blood-meridian-early-drafts-and-history.html

- https://texashillcountry.com/monster-who-was-real-judge-holden/

- https://slate.com/culture/2012/10/cormac-mccarthys-blood-meridian-early-drafts-and-history.html

- Lincoln, Kenneth (2009). Cormac McCarthy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 14. ISBN 978-0230619678.

- Crystal, David (2015). Making a Point: The Pernickity Story of English Punctuation. London: Profile Book. p. 92. ISBN 978-1781253502.

- https://www.nytimes.com/1985/04/28/books/blood-meridian-by-cormac-mccarthy.html

- "Bloom on "Blood Meridian"". Archived from the original on 2006-03-24.

- "All Time 100 Novels". Time. 2005-10-16. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- Dalrymple, William. "Blood Meridian is the Great American Novel". Reader's Digest.

McCarthy’s descriptive powers make him the best prose stylist working today, and this book the Great American Novel.

- New York Times, Sunday Magazine, May 21, 2006, p. 16.

- Wallace, David Foster. "Overlooked". Salon. Retrieved 2014-04-16.

- "Gus Van Sant Interviews David Foster Wallace". Retrieved 2014-04-16.

- Canfield, p. 37.

- Owens, p. 9.

- Shaviro, pp. 111–112.

- https://www.nytimes.com/1985/04/28/books/blood-meridian-by-cormac-mccarthy.html

- John, Jurgensen (November 20, 2009). "Cormac McCarthy". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- Balchack, Brian (May 9, 2014). "William Monahan to adapt Blood Meridian". MovieWeb. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- Franco, James (July 6, 2014). "Adapting 'Blood Meridian'". Vice. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- Stax (May 10, 2004). "Ridley Scott Onboard Blood Meridian?". IGN. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- Essman, Scott (June 3, 2008). "INTERVIEW: The great Ridley Scott Speaks with Eclipse by Scott Essman". Eclipse Magazine. Archived from the original on June 4, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- Horn, John (August 17, 2008). "Cormac McCarthy's 'The Road' comes to the screen". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2009. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- Friendman, Roger (January 3, 2011). "Exclusive: James Franco Planning to Direct Faulkner, Cormac McCarthy Classics". Showbiz411. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- Kroll, Justin (May 5, 2016). "Russell Crowe in Talks to Star in James Franco-Directed 'Blood Meridian'". Variety. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

Bibliography

- Canfield, J. Douglas (2001). Mavericks on the Border: Early Southwest in Historical fiction and Film. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2180-9.

- Daugherty, Leo (1992). "Gravers False and True: Blood Meridian as Gnostic Tragedy". Southern Quarterly. 30 (4): 122–133.

- Lilley, James D. (2014). "History and the Ugly Facts of Blood Meridian". Cormac McCarthy: New Directions. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-2767-3.

- Owens, Barcley (2000). Cormac McCarthy's Western Novels. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-1928-5.

- Schneider, Christoph (2009). "Pastorale Hoffnungslosigkeit. Cormac McCarthy und das Böse". In Borissova, Natalia; Frank, Susi K.; Kraft, Andreas (eds.). Zwischen Apokalypse und Alltag. Kriegsnarrative des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts. Bielefeld. pp. 171–200.

- Shaviro, Steven (1992). "A Reading of Blood Meridian". Southern Quarterly. 30 (4).

- Shaw, Patrick W. (1997). "The Kid's Fate, the Judge's Guilt: Ramifications of Closure in Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian". Southern Literary Journal: 102–119.

- Stratton, Billy J. (2011). "'el brujo es un coyote': Taxonomies of Trauma in Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian". Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory. 67 (3): 151–172. doi:10.1353/arq.2011.0020.

Further reading

- Sepich, John (2008). Notes on Blood Meridian. Southwestern Writers Collection Series. Foreword by Edwin T. Arnold (Revised and Expanded ed.). University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71821-0. Archived from the original on 2011-04-19. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Blood Meridian |