Blockbusting

Blockbusting is a business process of U.S. real estate agents and building developers to convince white property owners to sell their house at low prices, which they do by promoting fear in those house owners that racial minorities will soon be moving into the neighborhood. The agents then sell those same houses at much higher prices to black families desperate to escape the overcrowded ghettos.[1] Blockbusting became possible after the legislative and judicial dismantling of legally protected racially segregated real estate practices after World War II. By the 1980s it largely disappeared as a business practice, after changes in law and the real estate market.[2]

| Part of a series of articles on |

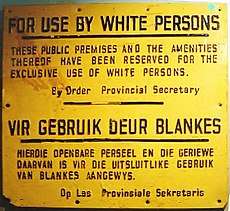

| Racial segregation |

|---|

|

| Segregation by region |

| Similar practices by region |

Background

From 1900–1970, around 6 million African Americans from the rural Southern United States moved to industrial and urban cities in Northern and Western United States during the Great Migration in effort to avoid the Jim Crow laws, violence, bigotry, and limited opportunities in the South. Resettlement to these cities peaked during World War I and World War II as northern and western cities recruited tens of thousands of blacks and whites including those from the South to work in the war industry and shipyards. Racial and class antagonisms heightened across the urban United States as a result of this influx of black residents and in part due to the over-crowding of cities. As American soldiers returned home in the aftermath of World War I and World War II, they struggled to find adequate housing and jobs in the cities that they left.

White homeowners in many U.S. cities regarded blacks as a social and economic threat to their neighborhoods.[3] If blacks moved into a neighborhood, home values in that neighborhood would decrease. Since white homeowners took great pride in their homes and often viewed them as their life's investment, they feared that allowing one black family to move into their neighborhood would ruin their life investments. To prevent their neighborhoods from becoming racially mixed, many cities kept their neighborhoods segregated with local zoning laws. Such laws required people of non-white ethnic groups to reside in geographically defined areas of the town or city, preventing them from moving to areas inhabited by whites.

This belief was substantiated by both racism and legislation. In 1934, the National Housing Act was signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, establishing the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). The FHA was commissioned by the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) to look at 239 cities and create "residential security maps" to indicate the level of security for real-estate investments in each surveyed city. These maps marked neighborhoods by quality from 'A' to 'D', with 'A' representing the higher income neighborhoods and 'D' representing the lower income neighborhoods. Some neighborhoods with some black population was given a 'D' rating and residents of those areas were refused loans. This practice, called redlining, gave whites an economic incentive to keep blacks out of their communities.

The areas that non-whites were allowed to live in were substandard. This was in part due to the over-crowding, which was exacerbated by the Great Migration. Often, several families were crowded into one unit. Because non-whites were confined to these small areas of the city, landlords were able to exploit their residents by charging high rents and ignoring repairs.

In 1917, in the case of Buchanan v. Warley, the Supreme Court of the United States voided the racial residency statutes that forbade blacks from living in white neighborhoods. The court ruled that the statutes violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[4] However, whites found a loophole in this case by using racially restrictive covenants in deeds, and real estate businesses informally applied them to prevent the sale of houses to Black Americans in White neighborhoods. To thwart the Supreme Court's Buchanan v. Warley prohibition of such legal business racism, state courts interpreted the covenants as a contract between private persons, outside the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment. However, in the Shelley v. Kraemer case in 1948, the Supreme Court ruled that the Amendment's Equal Protection Clause outlawed the states' legal enforcement of racially restrictive covenants in state courts.[5] In this event, decades of segregation practices were annulled, which had compelled blacks to live in over-crowded and over-priced ghettos. Freed by the Supreme Court from the legal restrictions, it became possible for non-whites to buy homes that had previously been reserved for white residents.

Generally, "blockbusting" denotes the real estate and building development business practices yielding double profits from anti-black racism. Real estate companies used deceitful tactics to make white homeowners think that their neighborhood was being "invaded" by non-white residents,[6] which in turn would encourage them to quickly sell their houses at below-market prices. The companies then sold that property to blacks who were desperate to escape inner-city ghettos at higher-than-market prices.

Due to redlining, African-Americans usually did not qualify for mortgages from banks and savings and loan associations. Instead, they resorted to land installment contracts at above market rates to buy a house. The harsh terms of these contracts often led to foreclosure, so these houses had a high turnover rate.[2] With blockbusting, real estate companies legally profited firstly from the arbitrage (the difference between the discounted price paid to frightened white sellers and the artificially high price paid by black buyers), secondly from the commissions resulting from increased real estate sales, and thirdly from their higher than market financing of the house sales to blacks.[2]

Methods

The term blockbusting might have originated in Chicago, Illinois, where real estate companies and building developers used agents provocateurs. Those were non-white people hired to deceive the white residents of a neighborhood into believing that black people were moving into the neighborhood. The houses that became vacant in that way enabled accelerated emigration of economically successful racial minority residents to better neighborhoods beyond the ghettos. The white residents were encouraged to quickly sell (at a loss) and emigrate to generally more racially homogeneous suburbs. Blockbusting was most prevalent on the West Side and South Side of Chicago, and also was heavily practiced in Bedford–Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, New York City; in the West Oak Lane and Germantown neighborhoods of Northwest Philadelphia; and on the East Side of Cleveland.

The tactics included:

- hiring black women to be seen pushing baby carriages in white neighborhoods, so encouraging white fear of devalued property

- hiring black men to drive through white neighborhoods with their radios blasting[7]

- hiring black youth to stage street brawls in front of white homes to generate feelings of an unsafe atmosphere

- selling a house to a black family in a middle-class white neighborhood to provoke white flight, before the community's properties decline considerably

- selling white neighborhood houses to black families, and afterwards placing real estate agent business cards in the neighbors' mailboxes, and saturating the neighborhood area with fliers offering quick cash for houses

- developers buying houses and dwelling buildings, and leaving them unoccupied to make the neighborhood appear abandoned – like a ghetto or a slum

Such practices can be described as psychological manipulation that usually frightened the remaining white residents into selling at a loss.

Blockbusting was very common and very profitable. For example, by 1962, when blockbusting had been practiced for some fifteen years, the city of Chicago had more than 100 real estate companies that had been, on average, "changing" two to three blocks a week for years.[2]

Reactions

In 1962, "blockbusting" – real estate profiteering – was nationally exposed by The Saturday Evening Post with the article "Confessions of a Block-Buster", wherein the author detailed the practices, emphasizing the profit gained from frightening white people to sell at a loss, in order to quickly resettle in racially segregated "better neighborhoods".[2] In response to political pressure from the cheated sellers and buyers, states and cities legally restricted door-to-door real estate solicitation, the posting of "FOR SALE" signs, and authorized government licensing agencies to investigate the blockbusting complaints of buyers and sellers, and to revoke the real estate sales licenses of blockbusters.[2] Likewise, other states' legislation allowed lawsuits against real estate companies and brokers who cheated buyers and sellers with fraudulent representations of declining property values, changing racial and ethnic neighborhood populations, increasing crime, and the "worsening" of schools, because of race mixing.[2]

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 established federal causes of action against blockbusting, including illegal real estate broker claims that blacks, Hispanics, et al. had or were going to move into a neighborhood, and so devalue the properties. The Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity was charged with the task of administering and enforcing this law. In the case of Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co. (1968), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Thirteenth Amendment authorized the federal government's prohibiting racial discrimination in private housing markets.[8] It thereby allowed black American legal claims to rescind the usurious land contracts (featuring over-priced houses and higher-than-market mortgage interest rates), as a discriminatory real estate business practice illegal under the Civil Rights Act of 1866, thus greatly reducing the profitability of blockbusting. Nevertheless, the said regulatory and statutory remedies against blockbusting were challenged in court; thus, towns cannot prohibit an owner's placing a "FOR SALE" sign before his house, in order to reduce blockbusting. In the case of Linmark Associates, Inc. v. Willingboro (1977), the Supreme Court ruled that such prohibitions infringe freedom of expression.[9] Moreover, by the 1980s, as evidence of blockbusting practices disappeared, states and cities began rescinding statutes restricting blockbusting.

Popular culture

The serious-comic television series All in the Family (1971–1979) featured "The Blockbuster", a 1971 episode about the practice, illustrating some real estate blockbusting techniques.

In the 2011 historical fantasy novel Redwood and Wildfire, author Andrea Hairston depicts actors being hired for blockbusting in Chicago, as well as the sense of betrayal experienced by others when they realized some black people were getting rich by participating in these exploitative schemes.

See also

- Black flight

- Inclusionary zoning

- Institutional discrimination in the housing market

- Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity

- Institutional racism

- Mortgage discrimination

- Planned shrinkage

- Racism

- Redlining

- Urban renewal

- White flight

References

- Rubenstein, James M. (2014). The Cultural Landscape: An Introduction to Human Geography (tenth ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 1-56639-147-4.

- Dmitri Mehlhorn (December 1998). "A Requiem for Blockbusting: Law, Economics, and Race-Based Real Estate Speculation". Fordham Law Review. 67: 1145–1161.

- "African Americans and World War I".

- Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917).

- Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948).

- Segrue, T. J. (2014). The Origins of the Urban Crisis. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Rothstein, Richard (2017). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (First ed.). New York. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-63149-285-3. OCLC 959808903.

- Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968).

- Linmark Associates, Inc. v. Willingboro, 431 U.S. 85 (1977).

Further reading

- Orser, W. Edward. (1994) Blockbusting in Baltimore: The Edmondson Village Story (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky)

- Pietila, Antero. (2010) Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee).

- Seligman, Amanda I. (2005) Block by Block: Neighborhoods and Public Policy on Chicago's West Side (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

- Ouazad, Amine. (2015) Blockbusting: Brokers and the Dynamics of Segregation, Journal of Economic Theory, Volume 157, May 2015, Pages 811–841.

- Rothstein, Richard. (2017) The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. First edition.