Black sparrowhawk

The black sparrowhawk (Accipiter melanoleucus), sometimes known as the black goshawk or great sparrowhawk, is the largest African member of the genus Accipiter.[2] It occurs mainly in forest and non-desert areas south of the Sahara, particularly where there are large trees suitable for nesting; favored habitat includes suburban and human-altered landscapes.[2] It preys predominantly on birds of moderate size, such as pigeons and doves, in suburban areas.[3]

| Black sparrowhawk | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Adult females of the light and dark morphs respectively | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Accipiter |

| Species: | A. melanoleucus |

| Binomial name | |

| Accipiter melanoleucus Smith, 1830 | |

| |

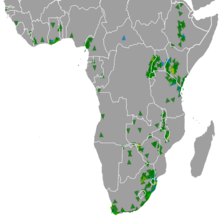

| global range Year-Round Range Summer Range Winter Range | |

Taxonomy

There are 2 subspecies of black sparrowhawk: Accipiter melanoleucus melanoleucus, which was named by A. Smith in 1830, and Accipiter melanoleucus temminckii, which was named by Hartlaub in 1855.[4] As described in the next section, the 2 subspecies occur in different regions of Africa and both belong to the genus Accipiter in the family Accipitridae along with other well-known members such as hawks and eagles, all of which are part of the order Accipitriformes.[5]

Description

Typically, both sexes of the black sparrowhawk have a predominantly black plumage with a white throat, breast and belly.[6] These white-breasted individuals are known as "white morphs" which are in the majority over most of the birds' range. The "black morph" variety is generally rare,[2][6][4] except along the coastal regions of South Africa, including the Cape Peninsula where they constitute 80% of the population.[7][8] (Black sparrowhawks do not occur more than about 200–300 km north of Cape Town along the South African west coast, where there are almost no trees.) These "black (or dark) morphs", when seen perched, can be black all over, but more commonly have a few white spots on the breast or a white throat of variable size. In flight both morphs show white and black barring on the underside of the wings and tail (see picture). The black morphs are not melanistic, as commonly alleged, as their plumage is not completely black, nor are they black as chicks or juveniles. There is no noticeable difference between the plumage of mature females and males, which can only be distinguished by size.[6] The tails are cross-barred with about three or four paler stripes, and the undersides of the wings with perhaps four or five. The legs are yellow, with large feet and talons.[4]

Young chicks have mid-grey eyes and white down, but when the feathers erupt they are predominantly brown. The full plumage of juveniles is a range of browns and russets with dark streaks along the head and, more conspicuously, down the chest. Commonly there are white or light-colored spots and streaks as well, mainly on the wings.[2] The brown plumage being a sign of immaturity, it does not attract as dangerously aggressively territorial behavior as a mature black-and-white bird would. As the young birds mature, their eyes change in color from mid-grey, through light brown, to dark red.[2]

Size

The black sparrowhawk is one of the world's largest Accipiters, only the Henst's, Meyer's and northern goshawk can match or exceed its size. As is common in the genus Accipiter, male black sparrowhawks are smaller than females. Typically the weights of males lie between 450 and 650 g (0.99 and 1.43 lb) while that of females lies in the 750 to 1,020 g (1.65 to 2.25 lb) range.[9][10][11] The typical total length is about 50 cm (20 in) and wingspan about 1 m (39 in).[3][10][12] As in most Accipiters, the tails are long (about 25 cm (9.8 in)), as are the tarsi (about 8 cm (3.1 in).[12] The features of the black sparrowhawk (and Accipiters in general) are reflective of the necessity to fly through dense arboreal habitats, although this species does most of its hunting in open areas (usually from a concealed perch in a tree).[10][11]

Colour polymorphism

The two different colour morphs (light and dark) exhibited by black sparrowhawks are inherited in a typical Mendelian manner, that suggests a one-locus, two-allele system in which the allele coding for the light morph is dominant.[7] The frequency of the morphs varies gradually throughout the South African range of black sparrowhawks, with the frequency of dark morphs declining from over 80% in the Cape Peninsula to under 20% in the northeast.[8] However, there are no differences of the morph distribution in relation to levels of urbanization.[13]

Dark morph black sparrowhawks might be more common on the Cape Peninsula due to pleiotropic properties of the genes that code for dark colouration, meaning that they code for an apparently unrelated trait. In the dark morph black sparrowhawk, those genes are also responsible for an improved blood parasite resistance compared to the light morph. The species breeds during the dry season in most parts of South Africa, but during the wet season on the Cape Peninsula, where blackflies and biting midges which transmit the haematozoan blood parasites (Leucocytozoon toddi and Haemoproteus nisi), may be more abundant. So, on the Cape Peninsula, black sparrowhawks gain a selective advantage from a dark colouration.[14]

When it comes to breeding on the Cape Peninsula, the morph combination of the parents also influences their productivity. Mixed‐pairs produce more offspring per year than pairs of the same morph, but this happens at the expense of the chicks' body condition.[15]

It has also been observed that dark morph black sparrowhawks have a higher hunting success in lower light conditions, while white morphs catch more prey in brighter conditions. This suggests, that the different morphs have a better crypsis (so that prey cannot detect them) at different light levels.[16]

Distribution and habitat

Black sparrowhawks are relatively widespread and common in sub-Saharan Africa and listed as not globally threatened by CITES.[4] Densities range from one pair per 13 square kilometers in Kenya to one pair per 38-150 square kilometers in South Africa.[4] On the Cape Peninsula, however, in the southwestern corner of South Africa, the nest are typically only 500 m (550 yds) apart in the pine plantations and other continuous or semi-continuous belts of trees.[9]

Both subspecies are only found in sub-Saharan Africa; A. m. temminckii inhabit much of the northwestern section including Senegal, the DRCongo, and Central African Republic, while A. m. melanoleucus is found from northeastern Africa southwards to South Africa.[2] They naturally inhabit patches of forest, rich woodlands and riverine strips extending into dry bush areas.[12] They can be found in many areas as long as they have large trees, including mangrove forest in coastal Kenya. Especially in southern Africa, black sparrowhawks have adapted to stands of the non-indigenous eucalyptus, poplar, and pine, all of which are grown commercially and are able to grow up to 15 m (49 ft) taller than native trees.[11][12] Their adaptability to secondary forest and cultivation (they are not uncommon around homesteads now) is one of the reasons why they are not as greatly impacted by deforestation as many African forest birds, and may actually increase in numbers where such stands have been placed in otherwise open country.[4][12] They are found in elevations from sea-level to 3,700 m (12,100 ft).[12]

In some areas, especially on the Cape Peninsula, these sparrowhawks face habitat competition with Egyptian geese (Alopochen aegyptiaca), an aggressive species known to steal the nests of the sparrowhawks.[3] This results in a costly loss for the sparrowhawks after the time and energy spent building the nest and may also lead to the death of current offspring.[3] However, sparrowhawks occasionally have more than 1 nest at a time, or they can readily build a new nest, so, in the event that one is usurped by an Egyptian goose, the pair will sometimes start breeding again in a nearby alternative nest; or they might wait until the geese have left the nest with their goslings, or they abandon breeding for that year.[3]

Urban habitats

Following a south and westwards range expansion of black sparrowhawks in South Africa, they also colonised the urban and suburban areas of Cape Town where they have thrived in the 21st century, with none of the expected negative impacts on their health that might have been expected from the disturbances associated with a novel climate (from a subtropical, summer rainfall regimen to a Mediterranean, winter rainfall region), or other possible sources of stress in their newly urbanised environments. This is probably due to the abundance of prey, mainly various species of Columbidae (the wide variety of pigeons and doves) in these urban areas, and, therefore, their lack of nutritional stress.[17] The level of urbanisation does not have a negative impact on their breeding success, either. Black sparrowhawks in more urbanised habitats are however more successful early in the season, while black sparrowhawks in less urbanised habitats perform better later in the breeding season.[18]

Behaviour

Vocalizations

They are mostly silent except during the breeding season.[19] Males make short, sharp "keeyp" contact calls when arriving with prey, to which the females respond with lower pitched "kek" sounds.[10][19] Before the male arrives with food, however, the female will solicit food with loud, high pitched drawn out "kweeeeee-uw" sounds.[10] Both sexes produce alarm calls, and characteristic mating cries. The chicks, but especially the juveniles, are very noisy, making high pitched "weeeeeeeeh" sounds, especially when soliciting food.

Diet

Black sparrowhawks prey primarily on mid-sized birds.[12] Most prey is spotted from a foliage-concealed perch, which is then killed in flight during a short flying dash. Less often, they stoop or chase prey seen during low or high flight over open country or near the canopy of trees and, in some cases, may even pursue prey on foot.[12] Although kills are often made in under a minute after the initial attack, occasionally this species may engage in a prolonged pursuit lasting several minutes.[20] They have been known to scan for ant swarms in order to predate birds that are attracted to these.[12] Most birds preyed on by this species are in the size range of 80–300 g (2.8–10.6 oz).[4] Doves are the primary prey of males, whereas females take a greater quantity of larger prey such as pigeons and francolins.[12] They also feed on poultry found in rural villages,[21] which have inadvertently been made available by humans. They also often take species such as rock pigeons that have flourished due to urban growth and settlement.[3] It is, in fact, one of the species that have been able to adapt to a changing habitat due to afforestation and urbanization by taking advantage of the increase in dove and pigeon populations.[3] With some regularity, they prey on other raptor species, including shikra, Ovambo sparrowhawk, African goshawk and wood owl.[12] Very occasionally, they may supplement their diet with small mammals, such as bats,[22] rodents and juvenile mongooses.[12] Black sparrowhawks can carry their plucked and decapitated prey over a distance of up to 12 km (7.5 mi), usually well above the canopy.[4][10]

Reproduction

A. m. temminckii usually breed between August and November while A. m. melanoleucus breed between May and October.[2] In Zambia, they breed at an intermediate time, between July and February. Black sparrowhawks in eastern Africa seemingly breed at almost any time of the year. These birds are particular about their nest sites; they prefer sites within the tree canopy to protect their offspring from adverse weather conditions and other predators.[11] Nests have been found from 7 to 36 m (23 to 118 ft) high in trees, though (in rare cases) have been found on the ground between large tree trunks.[12] However, the nests are usually not deep within the forest in order to stay within close proximity of the hunting habitat outside of the forest.[11]

The nests are made up of thousands of sticks collected by both parents and are usually lined with green eucalyptus leaves, pine needles, camphor leaves or other aromatic greenery possibly to deter carriers of diseases, such as mites and insects, due to the repelling smell of the leaves,[23] though greenery is often put in place weeks before the first egg is laid.[10] The nests can measure from 50 to 70 cm (20 to 28 in) in width and 30–75 cm (12–30 in) deep.[12]

Black sparrowhawks form monogamous pairs, though extra-pair matings are not uncommon.[24] A nesting pair will mate regularly throughout the breeding season, starting during courtship and continuing till after the chicks have fledged.[9] Once nest building or refurbishing starts the female becomes lethargic, and the male does nearly all the hunting and provisioning of the female and the chicks when they hatch.[10] Typically, the female will lay 2-4 eggs and the pair will incubate them for about 34–38 days until they hatch.[12][25] Most of the incubating is done by the female, but the male will take over after he has brought in prey. The female will then eat the food, and possibly bathe in a nearby stream, before taking over the incubation once again. This behavior persists into the brooding period,[9][10] with intense brooding by the female lasting up to 21 days[26] after which the female may also start to hunt for food, but only if the nest is left largely undisturbed by other predators. She remains the chief defender of the nest and the chicks.[9][10] The newly hatched chicks are semialtricial in that they are fully covered in white down feathers but cannot leave the nest since they rely on the parents for food, warmth, and protection.[25] After 37 to 50 days, the juveniles are fledged but the parents will continue to care for them for the next 37 to 47 days.[4][10][12] The entire time from egg-laying to the juvenile independence can, therefore, be 20 weeks, or 5 months.

Black sparrowhawks are known to attempt multiple brooding on occasions.[25] This behavior is exceeding rare in birds of prey. The second brood may be raised in the same nest, or in a second nest nearby, where the fledglings from the first brood will continue to be fed by the parents.[25] In the Cape Peninsula, South Africa, they are also known to build multiple nests in a season, and this behaviour is thought to be an adaptation to dealing with usurpation by Egyptian Geese.[27]

Nests are usually re-used year after year, frequently by the same pair. One nest is, in fact, known to have been used continuously for 32 years by a succession of pairs.[10][25]

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Accipiter melanoleucus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arkive. Black goshawk (Accipiter melanoleucus). In: Arkive: Images of Life on Earth. <http://www.arkive.org/black-goshawk/accipiter‐melanoleucus/%5B%5D>. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- Curtis O.E., Hockey P.A.R., Koeslag A. 2007. Competition with Egyptian geese Alopochen aegyptiaca overrides environmental factors in determining productivity of Black Sparrowhawks Accipiter melanoleucus. Ibis 149: 502‐508.

- del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J, editors. 2004. Handbook of the Birds of the World Vol. 2: New World Vultures to Guineafowl. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions.

- BirdLife International 2009. Accipiter melanoleucus. In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.1. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- Louette M. 2006. Moult, pied plumage and relationships within the genus of the black sparrowhawk Accipiter melanoleucus. Ostrich 77(1&2): 73-83.

- Amar, A. Koeslag, A. & Curtis, O (2013). Plumage polymorphism in a newly colonized black sparrowhawk population: classification, temporal stability and inheritance patterns. Journal of Zoology 289: 60–67. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2012.00963.x

- Amar, A., Koeslag, A., Malan, G., Brown, M. & Wreford, E. (2014). Clinal variation in the morph ratio of Black Sparrowhawks Accipiter melanoleucus in South Africa and its correlation with environmental variables. Ibis 156: 627-638. doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12157

- Koeslag, A. (2011) Black Sparrowhawks of the Cape Peninsula

- Hockey, P.A.R., Dean, W.R.J., Ryan, P.G. eds. (2005) Roberts - Birds of Southern Africa VII ed. pp. 520-522. The Trustees of the John Voelcker Bird Book Fund, Cape Town

- Malan G and Robinson ER. 2001. Nest-Site Selection by Black Sparrowhawks Accipiter melanoleucus: Implications for Managing Exotic Pulpwood and Sawlog Forests in South Africa. Environmental Management 28(2): 195-205.

- Raptors of the World by Ferguson-Lees, Christie, Franklin, Mead and Burton. Houghton Mifflin (2001)

- Sumasgutner, Petra; Rose, Sanjo; Koeslag, Ann; Amar, Arjun (1 March 2018). "Exploring the Influence of Urbanization on Morph Distribution and Morph-Specific Breeding Performance in a Polymorphic African Raptor". Journal of Raptor Research. 52 (1): 19–30. doi:10.3356/JRR-17-37.1. ISSN 0892-1016.

- Lei, Bonnie; Amar, Arjun; Koeslag, Ann; Gous, Tertius A.; Tate, Gareth J. (31 December 2013). "Differential Haemoparasite Intensity between Black Sparrowhawk (Accipiter melanoleucus) Morphs Suggests an Adaptive Function for Polymorphism". PLOS One. 8 (12): e81607. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0081607. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3876978. PMID 24391707.

- Tate, Gareth; Sumasgutner, Petra; Koeslag, Ann; Amar, Arjun (21 October 2016). "Pair complementarity influences reproductive output in the polymorphic black sparrowhawkAccipiter melanoleucus". Journal of Avian Biology. 48 (3): 387–398. doi:10.1111/jav.01100. ISSN 0908-8857.

- Tate, Gareth J.; Bishop, Jacqueline M.; Amar, Arjun (2 May 2016). "Differential foraging success across a light level spectrum explains the maintenance and spatial structure of colour morphs in a polymorphic bird". Ecology Letters. 19 (6): 679–686. doi:10.1111/ele.12606. ISSN 1461-023X. PMID 27132885.

- Suri, J.; Sumasgutner, P.; Hellard, É.; Koeslag, A.; Amar, A. (2017). "Stability in prey abundance may buffer Black Sparrowhawks Accipiter melanoleucus from health impacts of urbanization". Ibis. 159 (1): 38–54. doi:10.1111/ibi.12422.

- Rose, Sanjo; Sumasgutner, Petra; Koeslag, Ann; Amar, Arjun (2017). "Does Seasonal Decline in Breeding Performance Differ for an African Raptor across an Urbanization Gradient?". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 5. doi:10.3389/fevo.2017.00047. ISSN 2296-701X.

- Sinclair, I, and Ryan, P. 2003. Birds of Africa: south of the Sahara. Struik Nature, Cape Town, South Africa

- Del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. and Sargatal, J. (1994) Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume Two: New World Vultures to Guineafowl. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

- Louette M and Herroelen P. 2007. Comparative biology of the forest‐inhabiting hawks Accipiter spp. in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Ostrich 78(1): 21-28.

- Brown M (2006) Black Sparrowhawk takes a mid-meal nap. Gabar 17: 19–21.

- Malan G, Parasram WA, Marshall DJ. 2002. Putative function of green lining in black sparrowhawk nests: mite‐repellent role? South African Journal of Science 98: 358‐360.

- Martin, R.O., Koeslag, A., Curtis, O & Amar, A. (2014). Fidelity at the frontier: divorce and dispersal in a newly colonised raptor population. Animal Behaviour 93: 59-68. doi:org/10.1016/janbehav.2014.04.018

- Curtis O, Malan G, Jenkins A, Myburgh N. (2005). Multiple‐brooding in birds of prey: South African Black Sparrowhawks Accipiter melanoleucus extend the boundaries. Ibis 147: 11-16.

- Katzenberger, Jakob; Tate, Gareth; Koeslag, Ann; Amar, Arjun (1 October 2015). "Black Sparrowhawk brooding behaviour in relation to chick age and weather variation in the recently colonised Cape Peninsula, South Africa". Journal of Ornithology. 156 (4): 903–913. doi:10.1007/s10336-015-1199-0. ISSN 2193-7192.

- Sumasgutner, Petra; Millán, Juan; Curtis, Odette; Koeslag, Ann; Amar, Arjun (6 May 2016). "Is multiple nest building an adequate strategy to cope with inter-species nest usurpation?". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 16: 97. doi:10.1186/s12862-016-0671-7. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 4858914. PMID 27150363.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to black sparrowhawk. |