Black Diamond Coal Mining Company

The Black Diamond Coal Mining Company was formed in 1861, consolidating the Cumberland and Black Diamond coal mines in the region of Mount Diablo, in Contra Costa County, California.[1] During its years of operation as a mining company, it established three towns: Nortonville, California, Southport, Oregon, and Black Diamond, Washington. The company's mines in California and its settlement of Nortonville later became part of the Black Diamond Mines Regional Park and a California Historical Landmark.[2] Several railroad lines were built in California and Washington to support the company's mines, and the company operated numerous ships to transport its coal. As the mines played out and petroleum became the more common source of energy, the company closed its mines and transitioned into real estate as the Southport Land and Commercial Company.

| Private | |

| Industry | Mining |

| Successor | Southport Land and Commercial Company |

| Founded | June 15, 1861 in Martinez, California, USA |

| Founders |

|

| Headquarters | Martinez, California , USA |

Area served | California, Washington |

Founding in California

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, coal became the predominant energy source in the United States.[3] Coal would be transported by rail or ship, and each method incurred transportation costs that made coal costlier in distant areas, motivating miners in the west to search for local sources. The area around Mount Diablo was discovered to have veins of lignite coal, and several mines were opened, including the Cumberland and Black Diamond.[4]

In 1861, eight men representing the Cumberland Coal Mine and Black Diamond Coal Mine incorporated their mines into the Black Diamond Coal Mining Company, in order to "discover, dig, and develop coal … and to construct the necessary ways, railroads, and means to transport the same ... "[1] They developed roads from the mines to Clayton and New York Landing,[5] and built the Black Diamond Coal Mining Railroad between Nortonville and New York Landing.[6] New York Landing was renamed Black Diamond Landing, in recognition of the company.[7] Black Diamond also opened a wharf at Port Costa, California.

The company town of Nortonville was the largest of the coal towns around Mount Diablo,[8] with a population of over 900.[6] It was named for Noah Norton, who originally opened the Black Diamond mine and built the first two houses there. The first hotel, the Black Diamond Exchange, opened in 1863. A store, a schoolhouse, and more houses were gradually added. As was common at that time, lodges for several fraternal organizations were established, including International Organisation of Good Templars, Knights of Pythias, and Independent Order of Odd Fellows.[6] The company provided the land for Rose Hill Cemetery, a Protestant burial site for miners and other residents of the area, which was later donated to Contra Costa County. A fire destroyed many of the wooden buildings in 1878, and they were replaced with brick buildings.[9]

In 1865, the company's founders lost control of the company when a group of investors bought more than 85% of the stock and filled positions on the Board of Directors with their own members.[10] In 1866, the Black Diamond Coal Mining Company purchased the Bellingham Bay Coal Company and reorganized it as a subsidiary, operating its mines until closing them in 1878.[11]

Expansion into Oregon

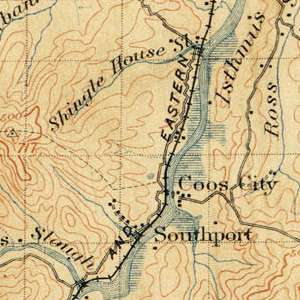

In the 1870s, the company purchased land in Coos County, Oregon.

B.B. Jones opened a 2,636‑acre mine on Isthmus Slough for Black Diamond Coal Mining Company. The Southport Mine operation was above water level. Cars transported the coal to the shipping point by gravity, and empty cars were pulled back up by horses.[12]

Southport was established as a company town.

A few years later, the nearby Newport Mine subsidized the Southport Mine, its competitor, to keep it closed.[12]

Black Diamond Coal Mining Company sold the mine in 1953, its last connection with coal mining.[10]

Expansion into Washington

The coal being mined from the mines in Nortonville was low quality. Needing a higher grade of coal to compete in the market, the company sent men north in 1880 to search for better sources.[13] They discovered high-quality coal outcroppings in Washington territory, and sent samples to California for testing. The coal they had found was bituminous, higher quality than the lignite coal being mined in the California mines,[14] and the company quickly began clearing trails, building houses, and opening the mine.[15]

The village established for the miners was named Black Diamond. Travel from Black Diamond to other towns was by horse or wagon or on foot over rough trails. Heavy equipment had to be brought in by pack animal, crossing the Cedar River six times from the nearest town, Renton.[16] Most homes were built on land owned by the company.[15] By 1885, the population of Black Diamond was 3500, many of them miners.[17]

The Columbia and Puget Sound Railroad extended its line to Black Diamond in 1884.[18] With the completion of the railroad line, the company closed its mines in California and began moving its miners and their families north.[15] Eventually, several trains a day would haul coal from the mines to Seattle to be sold there or shipped to San Francisco.[16] Black Diamond Coal Mining Company operated numerous ships to transport its coal between Washington and California, including the Ivanhoe, which was lost at sea in 1894.[19] To tow barges on the lake, it purchased the steamboat Chehalis.

The output of the Black Diamond mines in Washington when they were sold in 1904 was between 700 and 800 tons a day.[20]

The miners

Miners used drills and picks to knock loose the coal, working 12 hours a day, six days a week.[21] Trapper boys began working around age 13.[16] Although many of the Black Diamond Coal Mining Company miners were from Wales and Italy, immigrants from many other countries also came to work at the mines. To accommodate its international workers, "danger" signs were printed in Russian, Slovenian, Hungarian, Danish-Norwegian, Croatian, Spanish, Serbian, Lithuanian, Italian, Polish, Greek, Swedish, Bohemian, German, Finnish, and French.[22]

Methane gas and blackdamp were risks in mines. In 1876, six miners were suffocated by blackdamp generated from a powder explosion in a Black Diamond mine, and several others were severely burned.[6] Later, a 24-foot diameter fan was added to the mine for ventilation.[9]

In California, the Black Diamond Coal Mining Company employed 315 miners in 1870.[23] Mine employees included "100 coal-cutters and miners, 20 car-men, 11 car-drivers, 3 underground foremen, 4 engineers, 8 bunker men, and the rest are carpenters, watchmen, blacksmiths, firemen, door-tenders, furnace men, and slope men."[9]

From 1868 to 1905, the superintendent of the mines was Morgan Morgans, a native of Wales.[6][15]

Closing the mines

With the discovery of higher quality coal in Washington, the company closed its mines in California in 1884 and transferred its properties to a newly formed subsidiary, Southport Land and Commercial Company.[10] The Black Diamond Coal Company Engine No. 3 was sold to the Bellingham Bay and British Columbia Railroad.[9] When the miners departed the area around Mount Diablo in 1884, they left behind 200 miles of coal mine tunnels.[21] The mines and surrounding land later became part of the Black Diamond Mines Regional Preserve.[2]

When it closed its mines in Bellingham in 1878, Black Diamond had acquired a considerable amount of land around Bellingham Bay, and throughout the next 19 years, the company focused on the sale of its real estate.

In 1904, with demand for coal declining,[3] the company sold its mines in Black Diamond, Washington to the Pacific Coast Company.[24][25] When it sold its Southport Mine in Oregon and was no longer associated to the coal business, the company adopted the name of its subsidiary, Southport Land and Commercial Company, and concentrated on managing its real estate assets, as well as investing in Bellingham Bay Improvement Company. In the mid to late 1920s, the company attempted to reopen the Clayton Tunnel in Nortonville for coal mining, but were unsuccessful.[9]

References

- http://www.southport-land.com/PDFs/1861_06_15_1st_mtg_rev3.pdf Minutes of the first company meeting

- "California Historical Landmark #932". Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- "History of energy consumption in the United States, 1775–2009". U.S. Energy Information Administration. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- "Coal Mining". Clayton Historical Society & Museum. 2018-02-28. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Hulaniski, F. J. (1917). The History of Contra Costa County. The Elms Publishing Company. p. 139. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- Munro-Fraser, J. P. (1882). History of Contra Costa County, California. W. A. Slocum & Co.

history of contra costa county.

- Durham, David L. (1998). California's Geographic Names: A Gazetteer of Historic and Modern Names of the State. Word Dancer Press. ISBN 978-1-884995-14-9.

- Linsteadt, Sylvia. "Dark Treasure: Mount Diablo's Lost Coal Mines". Bay Nature Magazine. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Parent, Traci; Terhune, Karen (2009). Images of America: Black Diamond Mine Regional Preserve. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-6995-6.

- "History of Southport Land and Commercial Company". Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "Bellingham Bay Improvement Company Records, 1856–1986". Archives West, Orbis Cascade Alliance. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Peterson, Emil; Peters, Alfred (1952). A Century of Coos and Curry: History of Southwest Oregon. Binfords & Mort. pp. 398–399.

- "Who Laid Those Rusty Rails? — The Rail Line to Black Diamond". HistoryLink.org. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Mullineaux, Donal R. (1970). Geology of the Renton, Auburn, and Black Diamond Quadrangles, King County, Washington. Department of the Interior. p. 85.

- "Morgans, Morgan (1830–1905), Coal Mine Superintendent". HistoryLink.org. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Olson, Diane and Cory (1988). Black Diamond: Mining the Memories. Frontier Publishing. ISBN 978-0-939116-19-5.

- "Neighborhood of the week: Black Diamond is scenic, historic and quaint". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- Robertson, Donald B. (1995). Encyclopedia of Western Railroad History, Volume III (Oregon, Washington). Caxton Printers. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-8700-4366-6.

- "Ivanhoe Is Overdue". Morning Oregonian (10, 929). Oct 15, 1894. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- "Purchase of Black Diamond". The Sunday Oregonian. May 1, 1904. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Cuff, Denis. "Mount Diablo foothills: Historic mine, geology tours to get $2.2M expansion". The Mercury News. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- "Excerpts from the Feb/March 2011 Bugle". Maple Valley Historical Society. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- "California's 'Coal Mining' No Threat to Big Producers". Los Angeles Times. Dec 27, 1989. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Elfers, Richard (2017-08-30). "Without coal mining, there would be no Black Diamond". Covington-Maple Valley-Black Diamond Reporter. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- "Black Diamond Mines Sold". The Morning Astoria. May 14, 1904. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

External links

- Southport Land and Commercial Company official website