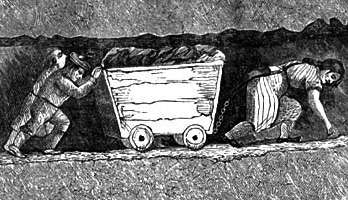

Hurrying

A hurrier, also sometimes called a coal drawer or coal thruster, was a child or woman employed by a collier to transport the coal that they had mined. Women would normally get the children to help them because of the difficulty of carrying the coal. Common particularly in the early 19th century, the hurrier pulled a corf (basket or small wagon) full of coal along roadways as small as 0.4 metres (16 in) in height. They would often work 12-hour shifts, making several runs down to the coal face and back to the surface again.[1][2]

Some children came from the workhouses and were apprenticed to the colliers. Adults could not easily do the job because of the size of the roadways, which were limited on the grounds of cost and structural integrity.[2] Hurriers were equipped with a "gurl" belt – a leather belt with a swivel chain linked to the corf. They were also given candles as it was too expensive to light the whole mine.[2]

Roles

Children as young as three or four were employed, with both sexes contributing to the work.[3][4] The younger ones often worked in small teams, with those pushing the corf from the rear being known as thrusters. The thrusters often had to push the corf using their heads, leading to the hair on their crown being worn away and the child becoming bald.[4]

Some children were employed as coal trappers, particularly those not yet strong enough to pull or push the corf. This job saw the child sit in a small cutting waiting for the hurriers to approach. They would then open the trapdoors to allow the hurrier and his cargo through. The trappers also opened the trapdoors to provide ventilation in some locations.[3][5][6]

As mines grew larger the volume of coal extracted increased beyond the pulling capabilities of children. Instead, horses guided by coal drivers were used to pull the corves. These drivers were usually older children between the ages of 10 and 14.[6]

Working conditions

Workers in coal mines were naked due to the heat and the narrow tunnels that would catch on clothing. Men and boys worked completely naked, while women and girls would generally strip to the waist; but in some mines might be naked also. In testimony before a Parliamentary commission, it was stated that working naked in confined spaces "... it is not to be supposed but that where opportunity thus prevails sexual vices are of common occurrence."[7]

Legislation

In August 1842 the Children's Employment Commission drew up an act of Parliament which gave a minimum working age for boys in mines, though the age varied between districts and even between mines. The Mines and Collieries Act 1842 also outlawed the employment of women and girls in mines.[2][3] In 1870 it became compulsory for all children aged between five and thirteen to go to school, ending much of the hurrying. It was still a common profession for school leavers well into the 1920s.[2]

The 1969 song The Testimony of Patience Kershaw[8] by Frank Higgins (recorded by Roy Bailey[9] and The Unthanks) is based on the testimony of Patience Kershaw (aged 17) when she spoke to the Children's Employment Commission.[10] Her testimony includes: "The bald place upon my head is made by thrusting the corves ... I hurry the corves a mile and more underground and back; they weigh 3 cwt ... The getters that I work for are naked except for their caps ... Sometimes they beat me if I am not quick enough".[11] It was published in My Song Is My Own (compiled by Kathy Henderson, Pluto Press, 1979).[12]

References

- Channel 4. "The Worst Jobs in History - Hurrier". Accessed from the Wayback Machine on 13 November 2009.

- HalifaxToday.co.uk. "The Nature Of Work Archived 2006-10-07 at the Wayback Machine". Accessed 17 February 2007.

- North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers. 2007. "Ages at which children and young persons are employed in coal mines Archived 2007-05-17 at the Wayback Machine". Accessed 17 February 2007.

- Rev. T. M. Eddy. July 1854. "Women in the British Mines". Freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com, Accessed 17 February 2007.

- Durham Mining Museum, "Mining Occupations". Accessed 19 February 2007.

- Riley, Bill. Pitwork.net. "Early Coal Mining History: Child Labour Archived 2012-12-24 at Archive.today". Accessed 13 November 2009.

- "Modern History Sourcebook: Women Miners in English Coal Pits". Fordham University. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- "Testimony of Patience Kershaw". Sniff.numachi.com. Retrieved 2016-08-09.

- If I Knew Who the Enemy Was Fuse Records CF 284; 1979

- "Testimony Gathered by Ashley's Mines Commission, 1842". Victorianweb.org. 2002-09-26. Retrieved 2016-08-09.

- Lloyd, A. L. (1975) Folk Song in England. Frogmore: Granada Publishing ISBN 0-586-08210-7; p. 327

- "Although the Honourable Gentlemen of the Commission may have been hearing the shocking news for the first time, contemporary songs and broadsheets, like "The Collier Lass", had made the predicament of the women and children working in the mines common knowledge in the streets."--Henderson, K. et al. My Song Is My Own; pp. 151-52

External links

| Look up hurrying in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- "Mining in the Victorian Age" – National Coal Mining Museum for England.

- "The Pit in Poems" – This Is Lancashire.