El Al Flight 1862

On 4 October 1992, El Al Flight 1862, a Boeing 747 cargo aircraft of the then state-owned Israeli airline El Al, crashed into the Groeneveen and Klein-Kruitberg flats in the Bijlmermeer (colloquially "Bijlmer") neighbourhood (part of Amsterdam-Zuidoost) of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. From the location in the Bijlmermeer, the crash is known in Dutch as the Bijlmerramp (Bijlmer disaster).

Aftermath of the disaster | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 4 October 1992 |

| Summary | Crashed following dual engine separation and loss of control |

| Site | Amsterdam-Zuidoost, Netherlands 52°19′8″N 4°58′30″E |

| Total fatalities | 43 |

| Total injuries | 26 |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 747-258F |

| Operator | El Al |

| Registration | 4X-AXG |

| Flight origin | John F. Kennedy International Airport, New York City, US |

| Stopover | Amsterdam Schiphol Airport, Netherlands |

| Destination | Ben Gurion International Airport, Tel Aviv, Israel |

| Occupants | 4 |

| Passengers | 1 |

| Crew | 3 |

| Fatalities | 4 |

| Survivors | 0 |

| Ground casualties | |

| Ground fatalities | 39 |

| Ground injuries | 26 (11 serious, 15 minor) |

A total of 43 people were officially reported killed including the aircraft's three crew members, a non-revenue passenger in a jump seat, and 39 people on the ground.[1]:9[2] In addition to these fatalities, 11 people were seriously injured and 15 people received minor injuries.[1][2][3] The exact number of people killed on the ground is disputed, as the building housed many undocumented immigrants.[4]

Flight

On 4 October 1992, the cargo aircraft, a Boeing 747-258F,[lower-alpha 1] registration 4X-AXG, travelling from John F. Kennedy International Airport New York to Ben Gurion International Airport in Israel, made a stopover at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport. During the flight from New York to Schiphol, three issues were noted: fluctuations in the autopilot speed regulation, problems with a radio, and fluctuations in the voltage of the electrical generator on engine number three, the inboard engine on the right wing that would later detach from the aircraft and initiate the accident.

The jet landed in Schiphol at 2:40 pm for cargo loading and crew change.[1]:7 The aircraft was refuelled and the observed issues were repaired, at least provisionally. The crew consisted of Captain Yitzhak Fuchs (59), First Officer Arnon Ohad (32) and Flight Engineer Gedalya Sofer (61). A single passenger named Anat Solomon (23) was on board. She was an El Al employee based in Amsterdam and was travelling to Tel Aviv to marry another El Al employee.[5] Captain Fuchs was an experienced aviator, having flown as a fighter-bomber pilot in the Israeli air force in the late 1950s.[6] He had over 25,000 flight hours, including 9,500 hours on the Boeing 747.[1]:9 First officer Ohad had less experience than either crew member having logged 4,288 flight hours, with 612 of them on the Boeing 747.[1]:10 Flight engineer Sofer was the most experienced crew member on the flight, having clocked up more than 26,000 hours of flight experience, with 15,000 of them on the Boeing 747.[1]:10–11

Flight

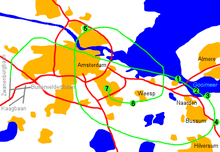

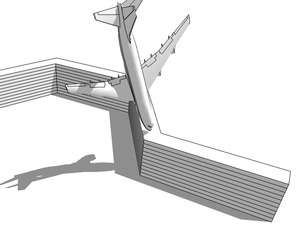

Flight 1862 was scheduled to depart at 5:30 pm, but was delayed until 6:20 pm. It departed from runway 01L (today known as runway 36C) on a northerly heading at 6:22 pm. Once airborne, the aircraft turned to the right on its departure route. Soon after the turn, at 6:27 pm, above the Gooimeer, a lake near Amsterdam, witnesses on the ground heard a sharp bang and saw falling debris, trail of smoke and a momentary flash of fire on the right wing while the aircraft was climbing through 1,950 metres (6,400 feet).[1]:7 Engine number three separated from the right wing of the aircraft, shot forward, damaged the wing flaps, then fell back and struck engine number four, tearing it from the wing. The two engines fell away from the aircraft, also ripping out a 10-meter (33-foot) stretch of the wing's leading edge. The loud noise attracted the attention of some pleasure boaters on the Gooimeer. The boaters notified the Netherlands Coastguard of two objects they had seen falling from the sky. One boater, a police officer, said he initially thought the two falling objects were parachutists, but as they fell closer he could see they were both plane engines.[7]

The first officer made a mayday call to air traffic control (ATC) and indicated that he wanted to return to Schiphol.[lower-alpha 2] At 6:28:45 pm, the first officer reported: "El Al 1862, lost number three and number four engine, number three and number four engine." ATC and the flight crew did not yet grasp the severity of the situation. Although the flight crew knew they had lost power from the engines, they did not see that the engines had completely broken off and that the wing had been damaged.[lower-alpha 3] The outboard engine on the wing of a 747 is visible from the cockpit only with difficulty and the inboard engine on the wing is not visible at all. Given the choices that the captain and crew made following the loss of engine power, the Dutch parliamentary inquiry commission that later studied the crash concluded that the crew did not know that both engines had broken away from the right wing.

On the night of the crash, the landing runway in use at Schiphol was runway 06. The crew requested runway 27 – Schiphol's longest – for an emergency landing,[1]:41–42 even though it meant landing with a 21-knot quartering tailwind.[lower-alpha 4]

The aircraft was still too high and close in to land when it circled back to the airport. It was forced to continue circling Amsterdam until it could reduce altitude to that required for a final approach to landing. During the second circle, the wing flaps were extended. The inboard trailing edge flaps extended, since they were powered by the number one hydraulic system, which was still functioning, but the outboard trailing edge flaps did not extend, because they were powered by the number four hydraulic system, which failed when the number four engine broke away from the wing. The partial flap condition meant that the aircraft would have a higher pitch attitude than normal as it slowed down. The leading edge slats extended on the left wing, but not on the right wing, because of the extensive damage sustained when the engines separated, which had also severely disrupted the air flow over the right wing. That differential configuration caused the left wing to generate significantly more lift than the damaged right wing, especially when the pitch attitude increased as the airspeed decreased. The increased lift on the left side increased the tendency to roll further to the right, both because the right outboard aileron was inoperative and because the thrust of the left engines was increased in an attempt to reduce the aircraft's very high sink rate. As the aircraft slowed, the ability of the remaining controls to counteract the right roll diminished. The crew finally lost almost all ability to prevent the aircraft from rolling to the right. The roll reached 90 degrees just before the impact with the apartments.[1]:39–40

At 6:35:25 pm, the first officer radioed to ATC: "Going down, 1862, going down, going down, copied, going down." In the background, the captain was heard instructing the first officer in Hebrew to raise the flaps and lower the landing gear.[1]:8

Crash

At 6:35:42 pm local time, the aircraft nose-dived from the sky and crashed into two high-rise apartment complexes in the Bijlmermeer neighbourhood of Amsterdam, at the corner of a building where the Groeneveen complex met the Klein-Kruitberg complex. It exploded in a fireball, which caused the building to partially collapse inward, destroying dozens of apartments. The cockpit came to rest east of the building, between the building and the viaduct of Amsterdam Metro Line 53; the tail broke off and was blown back by the force of the explosion.

During the last moments of the flight, the air traffic controllers made several desperate attempts to contact the aircraft. The Schiphol arrival controllers work from a closed building at Schiphol-East, not from the control tower. At 6:35:45 pm, the control tower reported to the arrival controllers: "Het is gebeurd" (lit., "It has happened", but often meaning "It is over"). At that moment a large smoke plume emitting from the crash scene was visible from the control tower. The aircraft had disappeared from arrival control radar. The arrival controllers reported that the aircraft had last been located 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi; 0.81 nmi) west of Weesp and emergency personnel were sent immediately.

At the time of the crash, two police officers were in Bijlmermeer checking on a burglary report. They saw the aircraft plummet and immediately sounded an alarm. The first fire trucks and rescue services arrived within a few minutes of the crash. Nearby hospitals were advised to prepare for hundreds of casualties. The complex was partly inhabited by immigrants from Suriname and Aruba, both of which are former Dutch colonies, and the death toll was difficult to estimate in the hours after the crash.[8][9]

Aftermath

The crash was also witnessed by a nearby fire station on Flierbosdreef street. First responders came upon a rapidly spreading fire of "gigantic proportions" that consumed all 10 floors of the buildings and was 120 metres (130 yd; 390 ft) wide, the length of a football field. There were no survivors from the crash point, only those who managed to escape from the remainder of the building.[10] Witnesses reported seeing people jumping out of the building to escape the fire.[11]

Hundreds of people were left homeless by the crash; the city's municipal buses were used to transport survivors to emergency shelters. Firefighters and police also were forced to deal with reports of looting in the area.[10]

Prime Minister Ruud Lubbers and Queen Beatrix visited the scene of the disaster the following afternoon. The prime minister said, "This is a disaster that has shaken the whole country."[9]

In the days immediately following the disaster, bodies of victims were recovered from the crash site. The mayor ordered rubble and aircraft wreckage removed, and investigators found the critical engine pylon fuse pins in the landfill. The two fallen engines were recovered from the Gooimeer, as were pieces of a 30-foot section of the right wing's leading edge.[7] The remains of the aircraft was transported to Schiphol for analysis.

The aircraft's flight data recorder was recovered from the crash site and was heavily damaged, with the tape broken in four places. The section containing the data from the last two and a half minutes of the flight was particularly damaged. The recorder was sent to the United States for recovery and the data was successfully extracted.[7] Despite intensive search activities to recover the cockpit voice recorder from the wreckage area, it was never found, even though El Al employees stated that it had been installed in the aircraft.[1]:23

Causes

In the event of excessive loads on the Boeing 747 engines or engine pylons, the fuse pins holding the engine nacelle to the wing are designed to fracture cleanly, allowing the engine to fall away from the aircraft without damaging the wing or wing fuel tank. Airliners are generally designed to remain airworthy in the event of an engine failure, so that they can be landed safely. Damage to a wing or wing fuel tank can have disastrous consequences. The Netherlands Aviation Safety Board found that the fuse pins had not failed properly, but instead had fatigue cracks prior to overload failure.[7] The Safety Board pieced together a probable sequence of events for the loss of engine three:

- Gradual failure by fatigue and then overload failure of the inboard mid-spar fuse pin at the inboard thin-walled location.

- Overload failure of the outer lug of the inboard mid-spar pylon fitting.

- Overload failure of the outboard mid-spar fuse pin at the outboard thin-walled and fatigue-cracked location.

- Overload failure of the outboard mid-spar fuse pin at the inboard thin-walled location.[1]:46

This sequence of consecutive failures caused the inboard engine and pylon to break free. Its trajectory after breaking off the wing caused it to slam into the outboard engine and rip it and its pylon off the wing. Serious damage was also caused to the leading edge of the right wing.[7] Both loss of hydraulic power and damage to the right wing prevented correct operation of the flaps that the crew later tried to extend in flight.

Research indicated that the crew were able to keep the aircraft in the air at first due to its high air speed (280 knots), even though the damage to the right wing, resulting in reduced lift, had made it more difficult to keep level. At 280 knots (520 km/h; 320 mph), there was nevertheless sufficient lift on the right wing to keep the aircraft aloft. Once it had to reduce speed for landing the amount of lift on the right wing was insufficient to enable stable flight, so a safe landing would have been very difficult to achieve. The aircraft then banked sharply to the right with very little chance of recovery.

The official probable causes were determined to be:[1]:46

The design and certification of the Boeing-747 pylon was found to be inadequate to provide the required level of safety. Furthermore the system to ensure structural integrity by inspection failed. This ultimately caused – probably initiated by fatigue in the inboard midspar fuse-pin – the no. 3 pylon and engine to separate from the wing in such a way that the no. 4 pylon and engine were torn off, part of the leading edge of the wing was damaged and the use of several systems was lost or limited. This subsequently left the flight crew with very limited control of the airplane. Because of the marginal controllability a safe landing became highly improbable, if not virtually impossible.

Victims

Forty-three people died in the accident: the four occupants of the aircraft (three crew and one non-revenue passenger) and 39 people on the ground.[1]:9 This was considerably lower than expected: the police had originally estimated a death toll of over 200[11] and Amsterdam Mayor Ed van Thijn had said that 240 people were missing.[8][9] Twenty-six people sustained non-fatal injuries; 11 of these were injured seriously enough to require hospital treatment.[1]:9

The belief has persisted that the actual number of victims killed in the crash was considerably higher. Bijlmermeer has a high number of residents living there illegally, particularly from Ghana and Suriname, and members of the Ghanaian community stated they lost a considerable number of undocumented occupants who were not counted among the dead.[12]

Memorial

A memorial, designed by architects Herman Hertzberger and Georges Descombes, was built near the crash site with the names of the victims.[13] Flowers are laid at a tree that survived the disaster, referred to as "the tree that saw it all" (de boom die alles zag). A public memorial is held annually to mark the disaster; no planes fly over the area for one hour out of respect for the victims.[4][14]

Health issues

Mental health care was available after the crash to all affected residents and service personnel. After about a year many residents and service personnel began approaching doctors with physical health complaints, which the affected patients blamed on the El Al crash. Insomnia, chronic respiratory infections, general pain and discomfort, impotence, flatulence, and bowel complaints were all reported. About 67% of the affected patients were found to be infected with mycoplasma, and suffered from symptoms similar to the Gulf War syndrome or chronic fatigue syndrome-like symptoms.

Dutch officials from government departments of transport and of public health asserted that at the time of the crash it was understood that there were no health risks from any cargo on the aircraft; Els Borst, minister of public health, stated that "geen extreem giftige, zeer gevaarlijke of radioactieve stoffen" ("no extremely toxic, very dangerous, or radioactive materials") had been on board. In October 1993, the nuclear energy research foundation Laka reported that the tail contained 282 kilograms (622 lb) of depleted uranium as trim weight, as did all Boeing 747s at the time; this was not known during the rescue and recovery process.[15][16]

It was suggested that studies be undertaken on the symptoms of the affected survivors and service personnel, but for several years these suggestions were ignored on the basis that there was no practical reason to believe in any link between the health complaints of the survivors and the Bijlmer crash site. In 1997 an expert testified in the Israeli parliament that dangerous products would have been released during combustion of the depleted uranium in the tail of the Boeing 747.

The first studies on the symptoms reported by survivors, performed by the Academisch Medisch Centrum, began in May 1998. The AMC eventually concluded that up to a dozen cases of autoimmune disorders among the survivors could be directly attributed to the crash and health notices were distributed to doctors throughout the Netherlands requesting that extra attention be paid to symptoms of auto-immune disorder, particularly if the patient had a link with the Bijlmer crash site. Another study, performed by the Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu, concluded that, although toxic products had been released at the time of the crash, the added risks of cancer were small, approximately one or two additional cases per ten thousand exposed persons. The RIVM also concluded that the chances of uranium poisoning were minimal.

Cargo

Soon after the disaster it was announced that the aircraft had contained fruit, perfumes, and computer components. Dutch Minister Hanja Maij-Weggen asserted that she was certain that it contained no military cargo.

The survivors' health complaints following the crash increased the number of questions about the cargo. In 1998 it was publicly revealed by El Al spokesman Nachman Klieman that 190 litres of dimethyl methylphosphonate, a CWC schedule 2 chemical which, among many other uses, can be used for the synthesis of Sarin nerve gas, had been included in the cargo. Israel stated that the material was non-toxic, was to have been used to test filters that protect against chemical weapons, and that it had been listed on the cargo manifest in accordance with international regulations. The Dutch foreign ministry confirmed that it had already known about the presence of chemicals on the aircraft. The shipment was from a US chemical plant to the Israel Institute for Biological Research under a US Department of Commerce license.[17][18] According to the chemical weapons site CWInfo, the quantity involved was "too small for the preparation of a militarily useful quantity of Sarin, but would be consistent with making small quantities for testing detection methods and protective clothing."[19][20]

Related accidents and aftermath

This was one of several accidents caused by problems with Boeing 707 and 747 engine pylons, which were nearly identical in design.[1]:38

In April 1968, an engine and pylon had fallen off a Boeing 707, being operated as BOAC Flight 712, resulting in five deaths.

On 16 January 1987, a Transbrasil Boeing 707 (PT-TCP) lost its No. 2 engine with 150 people on board. It landed without incident and was later ferried on 3 engines for repair.

In December 1991, China Airlines Flight 358 had crashed when its No. 3 and No. 4 engines fell off shortly after takeoff from Taipei, resulting in the death of all five occupants.[1]:32[21]

In January 1992, a Tampa Colombia 707 cargo flight was forced to return to Miami, when the No. 3 engine separated shortly after take-off.[1]:32[22]

In March 1992, a similar scenario – separation of the No. 3 and No. 4 engines – this time on a Boeing 707, occurred on a Trans-Air cargo flight. On this occasion, the crew was able to land safely at Istres Air Base in the south of France.[1]:32[23]

In March 1993, a Japan Airlines 747 cargo flight operated by Evergreen International Airlines similarly returned to Anchorage after the No. 2 engine detached.[1]:33[24]

After this accident, Boeing issued a service directive to all owners of the 747 regarding its fuse pins. Engines and pylons had to be removed from 747s and the fuse pins examined for defects. If cracks were present, the pins were to be replaced.

Depictions

The crash was depicted in National Geographic documentaries Seconds From Disaster episode "Amsterdam Air Crash" and Mayday episode "High Rise Catastrophe".

A 2013 film, In Het Niets ("From Nowhere", lit. "In The Nothing"), tells the fictional story of two illegal immigrants from Ghana living in the building at the time.[25]

See also

- Aviation safety

- China Airlines Flight 358

- American Airlines Flight 191

- List of accidents and incidents involving commercial aircraft

- Surinam Airways Flight 764 - 1989 aircraft crash involving several passengers from Bijlmer

Notes

- The aircraft was a Boeing 747-200F (for Freighter) model; Boeing assigns a unique customer code for each company that buys one of its aircraft, which is applied as an infix in the model number at the time the aircraft is built. The code for El Al is "58", hence "747-258F".

- Initially, the first officer was the pilot flying while the captain was making calls to ATC. These roles were immediately swapped following the engine separation.[1]:41

- In aviation, the term "lost" in this context means "engine failure", referring to an engine ceasing to provide thrust, rather than physically separating from the aircraft.

- The wind was initially from 40 degrees at 21 kt, and then 50 at 22. Runway 27 is aligned due west.

References

- "Aircraft accident report 92-11 : El Al Flight 1862 Boeing 747-258F 4X-AXG Bijlmermeer, Amsterdam 4 October 1992" (PDF). Nederlands Aviation Safety Board. 24 February 1994. Archived from the original on 26 June 2008.

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network

- "Two engines separate from the right wing and result in loss of control and crash of Boeing 747 freighter" (PDF). flightsafety.org. Flight Safety Foundation.

- "20 jaar Bijlmerramp" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Omroep Stichting (NOS). 4 October 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- Socolovsky, Jerome (6 October 1992). "Sole El Al Passenger Was Going Home To Get Married With AM-Netherlands-Crash, Bjt". AP NEWS. Associated Press. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- Aloni, Shlomo. "Last of the fighting 'Wooden Wonders': The DH Mosquito in Israeli service" September/October 1999 article with photo in Air Enthusiast No. 83.

- "Amsterdam Air Crash" Seconds From Disaster Season 2, Episode 15

- "The El Al Crash; In the Netherlands, The Struggle of Immigrants And Sudden Disaster". The New York Times. 11 October 1992. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- Montgomery, Paul L. (6 October 1992). "Dutch Search for Their Dead Where El Al Plane Fell". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- "Bijlmerramp". National Fire Service Documentation Centre (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 7 January 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- "El Al jumbo crashes in Amsterdam". BBC News. 4 October 1992. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- "The Bijlmer". Amsterdam Tourism. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 26 March 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Bijlmerramp voor zestiende keer herdacht" [Bijlmer disaster commemorated for sixteenth time] (in Dutch). 4 October 2008. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- Uijt de Haag P.A. and Smetsers R.C. and Witlox H.W. and Krus H.W. and Eisenga A.H. (28 August 2000). "Evaluating the risk from depleted uranium after the Boeing 747-258F crash in Amsterdam, 1992" (PDF). Journal of Hazardous Materials. 76 (1): 39–58. doi:10.1016/S0304-3894(00)00183-7. PMID 10863013. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- Henk van der Keur (May 1999). "Uranium Pollution from the Amsterdam 1992 Plane Crash". Laka Foundation. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- "Israel says El Al crash chemical 'non-toxic'". BBC. 2 October 1998. Archived from the original on 18 August 2003. Retrieved 2 July 2006.

- Greenberg, Joel (2 October 1998). "Nerve-Gas Element Was in El Al Plane Lost in 1992 Crash". New York Times. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- "Nerve Agent Precursor: Dimethyl Methyl Phosphonate". Archived from the original on 4 September 2013.

- Van Den Burg, Harm; Knip, Karel (30 September 1998). "Grondstof gifgas in Boeing El Al" [Raw material poison gas in Boeing El Al]. NRC Handelsblad (in Dutch). Rotterdam. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "Accident description, Sunday 29 December 1991, China Airlines Boeing 747-2R7F". ASN. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- "Accident description, Saturday 25 April 1992, Tampa Columbia Boeing 707-324C". ASN. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- "Accident description, Tuesday 31 March 1992, Trans-Air Service Boeing 707-321C". ASN. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- "Accident description, Wednesday 31 March 1993, Japan Air Lines Boeing 747–121". ASN. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- "Emotionele vertoning film Bijlmerramp" [Emotional screening of the Bijlmer disaster] (in Dutch). AT5. 23 October 2013. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

Further reading

- Theo Bean, Een gat in mijn hart: een boek gebaseerd op tekeningen en teksten van kinderen na de vliegramp in de Bijlmermeer van 4 oktober 1992. Zwolle: Waanders, 1993.

- Vincent Dekker, Going down, going down: De ware toedracht van de Bijlmerramp. Amsterdam: Pandora, 1999.

- Een beladen vlucht: eindrapport Bijlmer enquête. Sdu Uitgevers, 1999.

- Pierre Heijboer, Doemvlucht: de verzwegen geheimen van de Bijlmerramp. Utrecht: Het Spectrum, 2002.

- R. J. H. Wanhill and A. Oldersma, Fatigue and Fracture in an Aircraft Engine Pylon, Nationaal Lucht- en Ruimtevaartlaboratorium (NLR TP 96719). (Archive)

- This event is featured on the National Geographic Channel show Seconds From Disaster.

- The crash was featured on the 15th season of the National Geographic Channel and Discovery Channel Canada show Mayday or Air Crash Investigation. The episode is called High Rise Catastrophe. The computer graphics in the documentary wrongly painted the aircraft in El Al's passenger aircraft livery, while in reality, the crashed aircraft lacks the painting of Israel flag and airline identity, and only the word "Cargo" appear on both sides of the aircraft.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to El Al Flight 1862. |

- Aircraft accident report (Archive) Netherlands Aviation Safety Board. Originally issued in English, with a Dutch translation to be issued at a later time.

- Corrosion Doctors' entry on El Al Flight 1862

- Photographs of the disaster on AirDisaster.com

- Google Maps view of site

- Pre-disaster photos from Airliners.net

- cvr 781228. Planecrashinfo.com (4 October 1992). Retrieved on 9 September 2011.