Bhāskara II

Bhāskara (1114–1185) also known as Bhāskarācārya ("Bhāskara, the teacher"), and as Bhāskara II to avoid confusion with Bhāskara I, was an Indian mathematician and astronomer. He was born in Bijapur in Karnataka.[1]

Bhāskara II | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1114 AD Bijjaragi, Karnataka |

| Died | c. 1185 AD Chalisgaon (Patnadevi) |

| Other names | Bhāskarācārya |

| Academic work | |

| Era | Shaka era |

| Discipline | Mathematician |

| Main interests | Algebra, Calculus, Arithmetic, Trigonometry |

| Notable works | Siddhanta-Śiromani, Karaṇa-Kautūhala |

Bhāskara and his works represent a significant contribution to mathematical and astronomical knowledge in the 12th century. He has been called the greatest mathematician of medieval India.[2] His main work Siddhānta-Śiromani, (Sanskrit for "Crown of Treatises")[3] is divided into four parts called Līlāvatī, Bījagaṇita, Grahagaṇita and Golādhyāya,[4] which are also sometimes considered four independent works.[5] These four sections deal with arithmetic, algebra, mathematics of the planets, and spheres respectively. He also wrote another treatise named Karaṇā Kautūhala.[5]

Bhāskara's work on calculus predates Newton and Leibniz by over half a millennium.[6][7] He is particularly known in the discovery of the principles of differential calculus and its application to astronomical problems and computations. While Newton and Leibniz have been credited with differential and integral calculus, there is strong evidence to suggest that Bhāskara was a pioneer in some of the principles of differential calculus. He was perhaps the first to conceive the differential coefficient and differential calculus.[8]

On 20 November 1981 the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) launched the Bhaskara II satellite honouring the mathematician and astronomer.[9]

Date, place and family

Bhāskara gives his date of birth, and date of composition of his major work, in a verse in the Āryā metre:[5]

rasa-guṇa-porṇa-mahīsama

śhaka-nṛpa samaye 'bhavat mamotpattiḥ /

rasa-guṇa-varṣeṇa mayā

siddhānta-śiromaṇī racitaḥ //

This reveals that he was born in 1036 of the Shaka era (1114 CE), and that he composed the Siddhānta-Śiromaṇī when he was 36 years old.[5] He also wrote another work called the Karaṇa-kutūhala when he was 69 (in 1183).[5] His works show the influence of Brahmagupta, Śrīdhara, Mahāvīra, Padmanābha and other predecessors.[5]

He was born in a Deśastha Rigvedi Brahmin family[10] near Vijjadavida (believed to be Bijjaragi of Vijayapur in modern Karnataka). Bhāskara is said to have been the head of an astronomical observatory at Ujjain, the leading mathematical centre of medieval India. He lived in the Sahyadri region (Patnadevi, in Jalgaon district, Maharashtra).[11]

History records his great-great-great-grandfather holding a hereditary post as a court scholar, as did his son and other descendants. His father Maheśvara[11] (Maheśvaropādhyāya[5]) was a mathematician, astronomer[5] and astrologer, who taught him mathematics, which he later passed on to his son Loksamudra. Loksamudra's son helped to set up a school in 1207 for the study of Bhāskara's writings. He died in 1185 CE.

The Siddhānta-Śiromani

Līlāvatī

The first section Līlāvatī (also known as pāṭīgaṇita or aṅkagaṇita), named after his daughter, consists of 277 verses.[5] It covers calculations, progressions, measurement, permutations, and other topics.[5]

Bijaganita

The second section Bījagaṇita(Algebra) has 213 verses.[5] It discusses zero, infinity, positive and negative numbers, and indeterminate equations including (the now called) Pell's equation, solving it using a kuṭṭaka method.[5] In particular, he also solved the case that was to elude Fermat and his European contemporaries centuries later.[5]

Grahaganita

In the third section Grahagaṇita, while treating the motion of planets, he considered their instantaneous speeds.[5] He arrived at the approximation:[12]

- for close to , or in modern notation:[12]

- .

In his words:[12]

bimbārdhasya koṭijyā guṇastrijyāhāraḥ phalaṃ dorjyāyorantaram

This result had also been observed earlier by Muñjalācārya (or Mañjulācārya) mānasam, in the context of a table of sines.[12]

Bhāskara also stated that at its highest point a planet's instantaneous speed is zero.[12]

Mathematics

Some of Bhaskara's contributions to mathematics include the following:

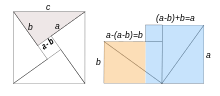

- A proof of the Pythagorean theorem by calculating the same area in two different ways and then cancelling out terms to get a2 + b2 = c2.[13]

- In Lilavati, solutions of quadratic, cubic and quartic indeterminate equations are explained.[14]

- Solutions of indeterminate quadratic equations (of the type ax2 + b = y2).

- Integer solutions of linear and quadratic indeterminate equations (Kuṭṭaka). The rules he gives are (in effect) the same as those given by the Renaissance European mathematicians of the 17th century

- A cyclic Chakravala method for solving indeterminate equations of the form ax2 + bx + c = y. The solution to this equation was traditionally attributed to William Brouncker in 1657, though his method was more difficult than the chakravala method.

- The first general method for finding the solutions of the problem x2 − ny2 = 1 (so-called "Pell's equation") was given by Bhaskara II.[15]

- Solutions of Diophantine equations of the second order, such as 61x2 + 1 = y2. This very equation was posed as a problem in 1657 by the French mathematician Pierre de Fermat, but its solution was unknown in Europe until the time of Euler in the 18th century.[14]

- Solved quadratic equations with more than one unknown, and found negative and irrational solutions.

- Preliminary concept of mathematical analysis.

- Preliminary concept of infinitesimal calculus, along with notable contributions towards integral calculus.[16]

- Conceived differential calculus, after discovering an approximation of the derivative and differential coefficient.

- Stated Rolle's theorem, a special case of one of the most important theorems in analysis, the mean value theorem. Traces of the general mean value theorem are also found in his works.

- Calculated the derivatives of trigonometric functions and formulae. (See Calculus section below.)

- In Siddhanta-Śiromani, Bhaskara developed spherical trigonometry along with a number of other trigonometric results. (See Trigonometry section below.)

Arithmetic

Bhaskara's arithmetic text Līlāvatī covers the topics of definitions, arithmetical terms, interest computation, arithmetical and geometrical progressions, plane geometry, solid geometry, the shadow of the gnomon, methods to solve indeterminate equations, and combinations.

Līlāvatī is divided into 13 chapters and covers many branches of mathematics, arithmetic, algebra, geometry, and a little trigonometry and measurement. More specifically the contents include:

- Definitions.

- Properties of zero (including division, and rules of operations with zero).

- Further extensive numerical work, including use of negative numbers and surds.

- Estimation of π.

- Arithmetical terms, methods of multiplication, and squaring.

- Inverse rule of three, and rules of 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11.

- Problems involving interest and interest computation.

- Indeterminate equations (Kuṭṭaka), integer solutions (first and second order). His contributions to this topic are particularly important, since the rules he gives are (in effect) the same as those given by the renaissance European mathematicians of the 17th century, yet his work was of the 12th century. Bhaskara's method of solving was an improvement of the methods found in the work of Aryabhata and subsequent mathematicians.

His work is outstanding for its systematisation, improved methods and the new topics that he introduced. Furthermore, the Lilavati contained excellent problems and it is thought that Bhaskara's intention may have been that a student of 'Lilavati' should concern himself with the mechanical application of the method.

Algebra

His Bījaganita ("Algebra") was a work in twelve chapters. It was the first text to recognize that a positive number has two square roots (a positive and negative square root).[17] His work Bījaganita is effectively a treatise on algebra and contains the following topics:

- Positive and negative numbers.

- The 'unknown' (includes determining unknown quantities).

- Determining unknown quantities.

- Surds (includes evaluating surds).

- Kuṭṭaka (for solving indeterminate equations and Diophantine equations).

- Simple equations (indeterminate of second, third and fourth degree).

- Simple equations with more than one unknown.

- Indeterminate quadratic equations (of the type ax2 + b = y2).

- Solutions of indeterminate equations of the second, third and fourth degree.

- Quadratic equations.

- Quadratic equations with more than one unknown.

- Operations with products of several unknowns.

Bhaskara derived a cyclic, chakravala method for solving indeterminate quadratic equations of the form ax2 + bx + c = y.[17] Bhaskara's method for finding the solutions of the problem Nx2 + 1 = y2 (the so-called "Pell's equation") is of considerable importance.[15]

Trigonometry

The Siddhānta Shiromani (written in 1150) demonstrates Bhaskara's knowledge of trigonometry, including the sine table and relationships between different trigonometric functions. He also developed spherical trigonometry, along with other interesting trigonometrical results. In particular Bhaskara seemed more interested in trigonometry for its own sake than his predecessors who saw it only as a tool for calculation. Among the many interesting results given by Bhaskara, results found in his works include computation of sines of angles of 18 and 36 degrees, and the now well known formulae for and .

Calculus

His work, the Siddhānta Shiromani, is an astronomical treatise and contains many theories not found in earlier works. Preliminary concepts of infinitesimal calculus and mathematical analysis, along with a number of results in trigonometry, differential calculus and integral calculus that are found in the work are of particular interest.

Evidence suggests Bhaskara was acquainted with some ideas of differential calculus.[17] Bhaskara also goes deeper into the 'differential calculus' and suggests the differential coefficient vanishes at an extremum value of the function, indicating knowledge of the concept of 'infinitesimals'.[18]

- There is evidence of an early form of Rolle's theorem in his work

- If then for some with

- He gave the result that if then , thereby finding the derivative of sine, although he never developed the notion of derivatives.[19]

- Bhaskara uses this result to work out the position angle of the ecliptic, a quantity required for accurately predicting the time of an eclipse.

- In computing the instantaneous motion of a planet, the time interval between successive positions of the planets was no greater than a truti, or a 1⁄33750 of a second, and his measure of velocity was expressed in this infinitesimal unit of time.

- He was aware that when a variable attains the maximum value, its differential vanishes.

- He also showed that when a planet is at its farthest from the earth, or at its closest, the equation of the centre (measure of how far a planet is from the position in which it is predicted to be, by assuming it is to move uniformly) vanishes. He therefore concluded that for some intermediate position the differential of the equation of the centre is equal to zero. In this result, there are traces of the general mean value theorem, one of the most important theorems in analysis, which today is usually derived from Rolle's theorem. The mean value theorem was later found by Parameshvara in the 15th century in the Lilavati Bhasya, a commentary on Bhaskara's Lilavati.

Madhava (1340–1425) and the Kerala School mathematicians (including Parameshvara) from the 14th century to the 16th century expanded on Bhaskara's work and further advanced the development of calculus in India.

Astronomy

Using an astronomical model developed by Brahmagupta in the 7th century, Bhāskara accurately defined many astronomical quantities, including, for example, the length of the sidereal year, the time that is required for the Earth to orbit the Sun, as approximately 365.2588 days which is the same as in Suryasiddhanta. The modern accepted measurement is 365.25636 days, a difference of just 3.5 minutes.[20]

His mathematical astronomy text Siddhanta Shiromani is written in two parts: the first part on mathematical astronomy and the second part on the sphere.

The twelve chapters of the first part cover topics such as:

- Mean longitudes of the planets.

- True longitudes of the planets.

- The three problems of diurnal rotation.(Diurnal motion is an astronomical term referring to the apparent daily motion of stars around the Earth, or more precisely around the two celestial poles. It is caused by the Earth's rotation on its axis, so every star apparently moves on a circle, that is called the diurnal circle.)

- Syzygies.

- Lunar eclipses.

- Solar eclipses.

- Latitudes of the planets.

- Sunrise equation

- The Moon's crescent.

- Conjunctions of the planets with each other.

- Conjunctions of the planets with the fixed stars.

- The paths of the Sun and Moon.

The second part contains thirteen chapters on the sphere. It covers topics such as:

- Praise of study of the sphere.

- Nature of the sphere.

- Cosmography and geography.

- Planetary mean motion.

- Eccentric epicyclic model of the planets.

- The armillary sphere.

- Spherical trigonometry.

- Ellipse calculations.

- First visibilities of the planets.

- Calculating the lunar crescent.

- Astronomical instruments.

- The seasons.

- Problems of astronomical calculations.

Engineering

The earliest reference to a perpetual motion machine date back to 1150, when Bhāskara II described a wheel that he claimed would run forever.[21]

Bhāskara II used a measuring device known as Yaṣṭi-yantra. This device could vary from a simple stick to V-shaped staffs designed specifically for determining angles with the help of a calibrated scale.[22]

Legends

In his book Lilavati, he reasons: "In this quantity also which has zero as its divisor there is no change even when many quantities have entered into it or come out [of it], just as at the time of destruction and creation when throngs of creatures enter into and come out of [him, there is no change in] the infinite and unchanging [Vishnu]".[23]

"Behold!"

It has been stated, by several authors, that Bhaskara II proved the Pythagorean theorem by drawing a diagram and providing the single word "Behold!".[24][25] Sometimes Bhaskara's name is omitted and this is referred to as the Hindu proof, well known by schoolchildren.[26]

However, as mathematics historian Kim Plofker points out, after presenting a worked out example, Bhaskara II states the Pythagorean theorem:

Hence, for the sake of brevity, the square root of the sum of the squares of the arm and upright is the hypotenuse: thus it is demonstrated.[27]

This is followed by:

And otherwise, when one has set down those parts of the figure there [merely] seeing [it is sufficient].[27]

Plofker suggests that this additional statement may be the ultimate source of the widespread "Behold!" legend.

See also

Notes

- Mathematical Achievements of Pre-modern Indian Mathematicians by T.K Puttaswamy p.331

- Chopra 1982, pp. 52–54.

- Plofker 2009, p. 71.

- Poulose 1991, p. 79.

- S. Balachandra Rao (13 July 2014), ನವ ಜನ್ಮಶತಾಬ್ದಿಯ ಗಣಿತರ್ಷಿ ಭಾಸ್ಕರಾಚಾರ್ಯ, Vijayavani, p. 17

- Seal 1915, p. 80.

- Sarkar 1918, p. 23.

- Goonatilake 1999, p. 134.

- Bhaskara NASA 16 September 2017

- The Illustrated Weekly of India, Volume 95. Bennett, Coleman & Company, Limited, at the Times of India Press. 1974. p. 30.

Deshasthas have contributed to mathematics and literature as well as to the cultural and religious heritage of India. Bhaskaracharaya was one of the greatest mathematicians of ancient India.

- Pingree 1970, p. 299.

- Scientist (13 July 2014), ನವ ಜನ್ಮಶತಾಬ್ದಿಯ ಗಣಿತರ್ಷಿ ಭಾಸ್ಕರಾಚಾರ್ಯ, Vijayavani, p. 21

- Verses 128, 129 in Bijaganita Plofker 2007, pp. 476–477

- Mathematical Achievements of Pre-modern Indian Mathematicians von T.K Puttaswamy

- Stillwell1999, p. 74.

- Students& Britannica India. 1. A to C by Indu Ramchandani

- 50 Timeless Scientists von K.Krishna Murty

- Shukla 1984, pp. 95–104.

- Cooke 1997, pp. 213–215.

- IERS EOP PC Useful constants. An SI day or mean solar day equals 86400 SI seconds. From the mean longitude referred to the mean ecliptic and the equinox J2000 given in Simon, J. L., et al., "Numerical Expressions for Precession Formulae and Mean Elements for the Moon and the Planets" Astronomy and Astrophysics 282 (1994), 663–683.

- White 1978, pp. 52–53.

- Selin 2008, pp. 269–273.

- Colebrooke 1817.

- Eves 1990, p. 228

- Burton 2011, p. 106

- Mazur 2005, pp. 19–20

- Plofker 2007, p. 477

References

- Burton, David M. (2011), The History of Mathematics: An Introduction (7th ed.), McGraw Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-338315-6

- Eves, Howard (1990), An Introduction to the History of Mathematics (6th ed.), Saunders College Publishing, ISBN 978-0-03-029558-4

- Mazur, Joseph (2005), Euclid in the Rainforest, Plume, ISBN 978-0-452-28783-9

- Sarkār, Benoy Kumar (1918), Hindu achievements in exact science: a study in the history of scientific development, Longmans, Green and co.

- Seal, Sir Brajendranath (1915), The positive sciences of the ancient Hindus, Longmans, Green and co.

- Colebrooke, Henry T. (1817), Arithmetic and mensuration of Brahmegupta and Bhaskara

- White, Lynn Townsend (1978), "Tibet, India, and Malaya as Sources of Western Medieval Technology", Medieval religion and technology: collected essays, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-03566-9

- Selin, Helaine, ed. (2008), "Astronomical Instruments in India", Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures (2nd edition), Springer Verlag Ny, ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2

- Shukla, Kripa Shankar (1984), "Use of Calculus in Hindu Mathematics", Indian Journal of History of Science, 19: 95–104

- Pingree, David Edwin (1970), Census of the Exact Sciences in Sanskrit, Volume 146, American Philosophical Society, ISBN 9780871691460

- Plofker, Kim (2007), "Mathematics in India", in Katz, Victor J. (ed.), The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook, Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691114859

- Plofker, Kim (2009), Mathematics in India, Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691120676

- Cooke, Roger (1997), "The Mathematics of the Hindus", The History of Mathematics: A Brief Course, Wiley-Interscience, pp. 213–215, ISBN 0-471-18082-3

- Poulose, K. G. (1991), K. G. Poulose (ed.), Scientific heritage of India, mathematics, Volume 22 of Ravivarma Samskr̥ta granthāvali, Govt. Sanskrit College (Tripunithura, India)

- Chopra, Pran Nath (1982), Religions and communities of India, Vision Books, ISBN 978-0-85692-081-3

- Goonatilake, Susantha (1999), Toward a global science: mining civilizational knowledge, Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-253-21182-8

- Selin, Helaine; D'Ambrosio, Ubiratan, eds. (2001), Mathematics across cultures: the history of non-western mathematics, Volume 2 of Science across cultures, Springer, ISBN 978-1-4020-0260-1

- Stillwell, John (2002), Mathematics and its history, Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-95336-6

Further reading

- W. W. Rouse Ball. A Short Account of the History of Mathematics, 4th Edition. Dover Publications, 1960.

- George Gheverghese Joseph. The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics, 2nd Edition. Penguin Books, 2000.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Bhāskara II", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews. University of St Andrews, 2000.

- Ian Pearce. Bhaskaracharya II at the MacTutor archive. St Andrews University, 2002.

- Pingree, David (1970–1980). "Bhāskara II". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 115–120. ISBN 978-0-684-10114-9.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |