Eccentricity (mathematics)

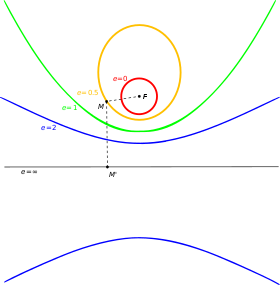

In mathematics, the eccentricity of a conic section is a non-negative real number that uniquely characterizes its shape.

More formally two conic sections are similar if and only if they have the same eccentricity.

One can think of the eccentricity as a measure of how much a conic section deviates from being circular. In particular:

Definitions

Any conic section can be defined as the locus of points whose distances to a point (the focus) and a line (the directrix) are in a constant ratio. That ratio is called the eccentricity, commonly denoted as e.

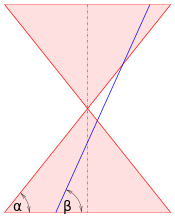

The eccentricity can also be defined in terms of the intersection of a plane and a double-napped cone associated with the conic section. If the cone is oriented with its axis vertical, the eccentricity is[1]

where β is the angle between the plane and the horizontal and α is the angle between the cone's slant generator and the horizontal. For the plane section is a circle, for a parabola. (The plane must not meet the vertex of the cone.)

The linear eccentricity of an ellipse or hyperbola, denoted c (or sometimes f or e), is the distance between its center and either of its two foci. The eccentricity can be defined as the ratio of the linear eccentricity to the semimajor axis a: that is, (lacking a center, the linear eccentricity for parabolas is not defined).

Alternative names

The eccentricity is sometimes called the first eccentricity to distinguish it from the second eccentricity and third eccentricity defined for ellipses (see below). The eccentricity is also sometimes called the numerical eccentricity.

In the case of ellipses and hyperbolas the linear eccentricity is sometimes called the half-focal separation.

Notation

Three notational conventions are in common use:

- e for the eccentricity and c for the linear eccentricity.

- ε for the eccentricity and e for the linear eccentricity.

- e or ϵ< for the eccentricity and f for the linear eccentricity (mnemonic for half-focal separation).

This article uses the first notation.

Values

| Conic section | Equation | Eccentricity (e) | Linear eccentricity (c) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circle | |||

| Ellipse | or where | ||

| Parabola | – | ||

| Hyperbola | or |

Here, for the ellipse and the hyperbola, a is the length of the semi-major axis and b is the length of the semi-minor axis.

When the conic section is given in the general quadratic form

the following formula gives the eccentricity e if the conic section is not a parabola (which has eccentricity equal to 1), not a degenerate hyperbola or degenerate ellipse, and not an imaginary ellipse:[2]

where if the determinant of the 3×3 matrix

is negative or if that determinant is positive.

Ellipses

The eccentricity of an ellipse is strictly less than 1. When circles (which have eccentricity 0) are counted as ellipses, the eccentricity of an ellipse is greater than or equal to 0; if circles are given a special category and are excluded from the category of ellipses, then the eccentricity of an ellipse is strictly greater than 0.

For any ellipse, let a be the length of its semi-major axis and b be the length of its semi-minor axis.

We define a number of related additional concepts (only for ellipses):

| Name | Symbol | in terms of a and b | in terms of e |

|---|---|---|---|

| First eccentricity | |||

| Second eccentricity | |||

| Third eccentricity | |||

| Angular eccentricity |

Other formulae for the eccentricity of an ellipse

The eccentricity of an ellipse is, most simply, the ratio of the distance c between the center of the ellipse and each focus to the length of the semimajor axis a.

The eccentricity is also the ratio of the semimajor axis a to the distance d from the center to the directrix:

The eccentricity can be expressed in terms of the flattening f (defined as for semimajor axis a and semiminor axis b):

(Flattening may be denoted by g in some subject areas if f is linear eccentricity.)

Define the maximum and minimum radii and as the maximum and minimum distances from either focus to the ellipse (that is, the distances from either focus to the two ends of the major axis). Then with semimajor axis a, the eccentricity is given by

which is the distance between the foci divided by the length of the major axis.

Hyperbolas

The eccentricity of a hyperbola can be any real number greater than 1, with no upper bound. The eccentricity of a rectangular hyperbola is .

Quadrics

The eccentricity of a three-dimensional quadric is the eccentricity of a designated section of it. For example, on a triaxial ellipsoid, the meridional eccentricity is that of the ellipse formed by a section containing both the longest and the shortest axes (one of which will be the polar axis), and the equatorial eccentricity is the eccentricity of the ellipse formed by a section through the centre, perpendicular to the polar axis (i.e. in the equatorial plane). But: conic sections may occur on surfaces of higher order, too (see image).

Celestial mechanics

In celestial mechanics, for bound orbits in a spherical potential, the definition above is informally generalized. When the apocenter distance is close to the pericenter distance, the orbit is said to have low eccentricity; when they are very different, the orbit is said be eccentric or having eccentricity near unity. This definition coincides with the mathematical definition of eccentricity for ellipses, in Keplerian, i.e., potentials.

Analogous classifications

A number of classifications in mathematics use derived terminology from the classification of conic sections by eccentricity:

- Classification of elements of SL2(R) as elliptic, parabolic, and hyperbolic – and similarly for classification of elements of PSL2(R), the real Möbius transformations.

- Classification of discrete distributions by variance-to-mean ratio; see cumulants of some discrete probability distributions for details.

- Classification of partial differential equations is by analogy with the conic sections classification; see elliptic, parabolic and hyperbolic partial differential equations.[3]

Eccentricity for data shapes

The eccentricity is also a concept which is used to characterize statistical distribution of data points around a common axis. For example, the eccentricity can be used to characterize shapes of jets of many particles.[4]

The definition closely follows the original "geometrical" concept, with one important difference – data points can have "weights". Such weights can lead to a deviation from the standard geometrical concept that assumes that all data points have the same contributions.

References

- Thomas, George B.; Finney, Ross L. (1979), Calculus and Analytic Geometry (fifth ed.), Addison-Wesley, p. 434. ISBN 0-201-07540-7

- Ayoub, Ayoub B., "The eccentricity of a conic section", The College Mathematics Journal 34(2), March 2003, 116-121.

- "Classification of Linear PDEs in Two Independent Variables". Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- Chekanov, S. V.; Proudfoot, J. (2010-06-25). "Searches for TeV-scale particles at the LHC using jet shapes". Physical Review D. American Physical Society (APS). 81 (11): 114038. arXiv:1002.3982. doi:10.1103/physrevd.81.114038. ISSN 1550-7998.