Berimbau

The berimbau (Portuguese pronunciation: [beɾĩˈbaw]) is a single-string percussion instrument, a musical bow, from Brazil. Originally from Africa where it receives different names,[1] the berimbau was eventually incorporated into the practice of the Afro-Brazilian martial art capoeira, the berimbau leads the capoeiristas movement in the roda—the faster the berimbau is playing the faster the capoeirista moves in the game. The instrument is known for being the subject matter of a popular song by Brazilian guitarist Baden Powell, with lyrics by Vinicius de Moraes. The instrument is also a part of Candomblé-de-caboclo tradition.

History

The berimbau's origins have not been fully researched, though it is most likely an adaptation of African gourde musical bows, as no Indigenous Brazilian or European people use musical bows.[1][2]

The way the berimbau and the m'bulumbumba of southwest Angola are made and played are very similar, as well as the tuning and basic patterns performed on these instruments. The assimilation of this African instrument into the Brazilian capoeira is evident also in other Bantu terms used for musical bows in Brazilian Portuguese, including urucungo, and madimba lungungu.

By the twentieth century, the instrument was with the jogo de capoeira (game of capoeira), which had come to be known as the berimbau, a Portuguese misnomer. The Portuguese used this word for their musical instrument the guimbarde, also known as a Jew's harp. As the Jew's harp and hungu shared some similarities when the latter was held in the mouth, the Portuguese referred to it as berimbau, akin to how the African lamellaphone came to be known in English as the "hand piano" or "thumb piano." The smaller type of the African bow (in which the performer's mouth is used as a resonator) was called the "berimbau de boca" (mouth guimbarde) whereas the gourd-resonating type became the "berimbau de barriga" (belly guimbarde).

The berimbau slowly came to replace the drum as the central instrument for the jogo de capoeira, which it is now famous for and widely associated with.[3]

Design

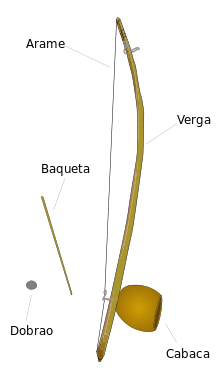

The berimbau consists of a wooden bow (verga – traditionally made from biribá wood, which grows in Brazil), about 4 to 5 feet (1.2 to 1.5 metres) long, with a steel string (arame – often pulled from the inside of an automobile tire) tightly strung and secured from one end of the verga to the other. A gourd (cabaça), dried, opened and hollowed-out, attached to the lower portion of the verga by a loop of tough string, acts as a resonator.

Since the 1950s, Brazilian berimbaus have been painted in bright colors, following local Brazilian taste; today, most makers follow the tourist consumer's quest for (pretended) authenticity, and use clear varnish and discreet decoration.

To play the berimbau, one holds it in one hand, wrapping the two middle fingers around the verga, and placing the little finger under the cabaça's string loop (the anel), and balancing the weight there. A small stone or coin (pedra or dobrão) is held between the index and thumb of the same hand that holds the berimbau. The cabaça is rested against the abdomen. In the other hand, one holds a stick (baqueta or vaqueta – usually wooden, very rarely made of metal) and a shaker (caxixi). One strikes the arame with the baqueta to produce the sound. The caxixi accompanies the baqueta. The dobrão is moved back and forth from the arame to change the pitch produced by the berimbau. The sound can also be altered by moving the cabaça back and forth from the abdomen, producing a wah-like sound.

Parts and accessories of the berimbau:

- Verga: wooden bow that makes up the main body of the Berimbau

- Arame: steel string

- Cabaça: opened, dried and hollowed out gourd-like fruit secured to the lower portion of the berimbau, used to amplify and resonate the sound

Calling the cabaça a gourd is technically a mistake. As far as Brazilian berimbaus are concerned, the fruit used for the berimbau's resonator, while still known in Brazil as cabaça ("gourd"), it is not technically a gourd (family Cucurbitaceae); instead, it is the fruit of an unrelated species, the tree Crescentia cujete (family Bignoniaceae), known in Brazil as calabaça, cueira, cuia,[4] or cabaceira.[5]

- Pedra or Dobrão: small stone or coin pressed against the arame to change the tone of the berimbau

- Baqueta: small stick struck against the arame to produce the sound

- Caxixi: small rattle that optionally accompanies the baqueta in the same hand

Capoeiristas split berimbaus in three categories:

- Gunga (others say Berra-boi): lowest tone

- Médio (others say Viola): medium tone

- Viola (Violinha if the medium tone is Viola): highest tone

These categories relate to sound, not to size. The berimbau's quality does not depend on the length of the verga or the size of the gourd, rather on the diameter and hardness of the verga's wood and the quality of the cabaça.

Sound

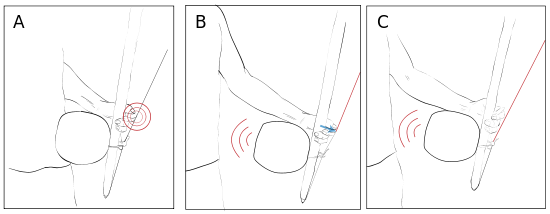

The berimbau, as played for capoeira, basically has three sounds: the open string sound, the high sound, and the buzz sound.

- In playing the buzz sound, one holds easily the gourd closed against one's belly, while touching the string with the dobrão. A muted "tch" sound emerges.

- To play the open string sound, one strikes the string less than an inch up from the gourd string, with the bow balanced on the little finger so that the gourd is opened. One can grossly tune the open sound, by loosening the arame, and by sliding the gourd a little up or down from the place where the sound is best.

- To produce the high sound, one must hold the bow in the same way, gourd opened, and forcefully press the dobrão on the string. The sound differs from the low sound in tone and in timbre. Old recordings and musicians report that the difference in tone used to be about 1 tone (the interval from C to D). One can press the dobrão away enough from the gourd for this only if the bow is about 4 feet (1.2 m) to 4 feet 2 inches (122 to 127 cm); that was the length of the bows in the 1940s and 1950s. Today, many berimbaus are overgrown to 5 feet (150 cm), and tuning options are limited in berimbau ensembles.

Other sounds may appear in a berimbau performance, but only these define capoeira's rhythmic patterns (except Iuna).

Closing and opening the gourd while the string resounds produces a wah-wah effects, which depends on how large the gourd opening is. Whether this effect is desirable or not is a matter of controversy. Pressing the dobrão after striking the string is a widely used technique; so is closing neatly the gourd while the string resounds to shut off the sound. A specific toque requires the open string sound with closed gourd. Musicians use whatever sound they may get out of the string. It is not often considered bad practice to strike other parts of the instrument. As with most aspects of playing the berimbau, the names of the techniques differ from teacher to teacher. Most teachers, and most students, worry more about producing a nice sound than about naming the individual sounds.

Of course, the strength (velocity, accent) with which one lets the baqueta hit the string is paramount to rhythm quality. The open sound is naturally stronger (meaning that, for a constant-strength strike, the other two sound weaker), but the musician may decide which strikes to stress. Also, the sound tone shifts a little with the strength of the strike, and some sophisticated toques make use of this.

Use in capoeira

In capoeira, the music required from the berimbau is essentially rhythmic. Most of the patterns, or toques, derive from a single 8 unit basic structure:

xxL.L.L.

(Note: all characters, including the '.', denote equal time: 'x' = the buzz sound; 'L' = low tone; 'H' = high tone; '.' = a rest, no action.)

Notation key:

. rest

x buzzed note

L Low tone

H High tone

(...) Bar of 2 to 4 beats, 8 - 16 subdivisions/units

(..|..) Two or more bars

., x, L, H are of equal length and represent the smallest subdivision of the bar

Capoeira musicians produce many variations upon this pattern. They give names to known variations, and when such a named variation occurs repeatedly (but not exclusively) while playing, they call what they are playing by the name of that variation. The most common names are "Angola" and "São Bento Grande". There is much talking about the meaning of these terms. There is no short way to wisdom in capoeira; one has to make up one's own mind.

In traditional capoeira, three Berimbaus play together (accompanied by two pandeiros, one atabaque, one reco-reco and an agogo. Each berimbau holds a position in relation to the "roda":

- The gunga plays "Angola" and is most commonly played by a Mestre or the highest grade Capoeirista around. Depending on the style of the group and the personality of the individual, the gunga may improvise a lot or stick strictly to the main rhythm. The person playing the gunga at the beginning of a roda is often the leader of the roda and the other instruments follow as well. The gunga player may also lead the singing, which is made easier by the simple rhythm and little variation that he plays. The gunga is used to call players to the pé-do-berimbau (foot of the berimbau, where players enter the game).

- The médio plays "Sao Bento Pequeno". For instance, while the gunga may play a simple, eight-unit pattern like (xxL.H.H.), the viola (or médio) can play a sixteen-unit variation, like (xxL.xLHL|.xL.H.H.). The dialog between gunga and viola (or médio) gives the toque its character. In the context of capoeira Angola, the médio inverts the gunga's melody (Angola toque): (xxL.H...) by playing São Bento Pequeno: (xxH.L...) with moderate improvisation.

- The viola plays "Sao Bento Grande". Mostly variations and improvisations. It may described as the "lead guitar" of the "bateria".

There is no further general rule. Every master has his own requirements for the interaction between musicians. Some want all the instruments in unison. Others reserve uniform play for beginners and require significant variation from their advanced students, as long as the characteristic of the "toque" is not blurred.

Tuning in capoeira is also loosely defined. The berimbau is a microtonal instrument and while one can be tuned to play a major or minor 2nd, the actual tone is approximately a neutral second lying between a whole and half tone.

The berimbaus may be tuned to the same pitch, differing only in timbre. More commonly, low note of the médio is tuned in unison to the high note of the Gunga, and likewise for the viola to the médio. Others like to tune the instruments in 4ths (C, F, B flat) or a triad (C, E, G). Any tuning is acceptable provided it sounds good to the master's ear.

There are countless different rhythms or toques played on the berimbau. Capoeiristas and masters engage in endless debate about the denominations of the rhythms, the loose or tight relations of any definite rhythmic pattern to a toque name, to speed of execution, and to the type of Capoeira game it calls for. Each group delivers its own definitions to beginners.

Toques

Common toques names are:

- Angola: rests on (does not play) the last beat of the basic leaving (xxL.H...)

- São Bento Pequeno de Angola Invertido: similar to Angola but with the high and low tones reversed (xxH.L...). São Bento Pequeno is typically played on Médio in conjunction with Angola on the Gunga.

- São Bento Grande: adds an extra hit to São Bento Pequeno, (xxH.L.L.)

- São Bento Grande de Regional (or simply Regional): an innovation of Mestre Bimba, is often played in the two bar pattern (xxL.xxH.|xxL.L.H.)

- Toque de Iúna: introduced to capoeira by Mestre Bimba. (L-L-L-L-L-xxL-L.) (the '-' = touching the dobrão to the arame without hitting).

- Cavalaria: in the past, used to warn Capoeiristas of the approach of police. (L.xxL.xxL.xxL.H.) is one example, variations exist.

In notating the toques, it is a convention to begin with the two buzzed tones, however it is worthwhile to note that they are pickups to the downbeat, and would more properly be transcribed: xx(L.H...xx)

São Bento Grande as played in a regional setting places the main stress or downbeat at the final L so that it sounds: (L.xxH.L.|L.xxH.L.L)

Other toques include Idalina: (L.L.x.H.|xxL.L.H.), Amazonas: (xxLLxxLH|xxLLLLLH), Benguela: (xxL.H.H.), all deriving from the basic capoeira pattern. The toque called "Santa Maria" is a four bar transcription of the corridos "Santa Maria" and "Apanha Laranja no Chão Tico Tico". (xxL.LLL.|xxL.LLH.|xxH.HHH.|xxH.LHL.)

Capoeiristas also play samba, before or after capoeira, with the proper toques, deriving from the samba de roda rhythmic pattern: (xxH.xxH.xx.H.HH.)

Berimbau players in other styles of music

- Electronic artist and multi-instrumentalist Bibio makes use of the berimbau on the track "K Is For Kelson", the first single from his 2011 album Mind Bokeh.

- Candomblé-de-caboclo songs have been recorded by ethnomusicologists to the accompaniment of berimbau. Musicians have also played Ketu, Gêgê and Angola candomblé rhythm patterns on berimbau, but this does not appear to have any relationship either with the cults or with capoeira.

- Berimbau has appeared in a number of bands as a marker of Afro-Brazilian origin.

- Nana Vasconcelos, since the late 1970s, has played berimbau and other percussion with modern jazz musicians worldwide.

- Paulinho Da Costa is a studio musician.

- Max Cavalera is the lead singer and guitarist in metal bands Sepultura, Soulfly and Cavalera Conspiracy.

- Airto Moreira - Brazilian percussionist; works with many musicians and combines many styles from different continents

- Okay Temiz - Turkish jazz drummer and percussionist; the berimbau is an instrument which he commands and used in many songs, the most famous of which is "Denizalti Rüzgarlari" from 1975

- Cut Chemist, turntablist of such groups as Ozomatli and Jurassic 5, made use of the berimbau in his single "The Garden," on his album The Audience's Listening.

- TaKeTiNa - The berimbau is used as a drone, along with the surdo, which serves as the "heartbeat", as part of the TaKeTiNa Rhythm Process, a musical, meditative group process for people who want to develop their awareness of rhythm.

- Minnesota metal band GRYZOR uses a modern contemporary version of the berimbau in their live show.

- Mauro Refosco, a Brazilian percussionist and member of bands Forró In The Dark and Atoms For Peace, plays the berimbau in the live rendition of the Atoms' "The Clock".

- Mickey Hart, percussionist for the Grateful Dead, played the berimbau on the song "Throwing Stones" from the CD In the Dark, as well as on several of his solo works.

Similar instruments

The Siddi of India, who are the descendants of East African immigrants, play a similar instrument called the malunga.

The Chamoru of Guam also play a similar instrument called belembao or belembaotuyan. The similarity between the names "berimbau" and "belembao" is intriguing since there is no acknowledged link between the Pacific society and Brazil, although it is most likely that knowledge of the African-derived berimbau was transported to Guam via Spanish colonial trade (Guam having once been under Spanish imperial influence).

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to berimbau. |

- Capoeira

- Capoeira songs

- Musical bow

- Malunga

- Belembaotuyan

Notes

- "Royal Museum for Central Africa, Belgium". Retrieved 2015-04-11.

- Funso S. Afọlayan (2004). Culture and Customs of South Africa. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32018-7. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Obi, T.J. Desch (2008). Fighting for Honor: The History of African Martial Art Traditions in the Atlantic World. Columbia, South Carolina, USA: University of South Carolina Press. p. 184. ISBN 9781570037184.

- O Estado de S. Paulo, 6–12 April 2011, Suplemento Agrícola, page 2

- Houaiss Dictionary

External links

- LiveCapoeira: Capoeira Instruments: The Berimbau

- Berimbau Manual: notes, sounds and rhythms, types of berimbau

- Berimbau Free berimbau instructional videos taught by Mestre Virgulino.

- language=en Berimbau how to set up a berimbau, how to play a berimbau, berimbau information

- As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls by Pat Metheny utilizes the Berimbau in some highly original ways - played by Berimbau master - Nana Vasconcelos

- Berimbau song lyrics by Vinícius de Moraes

- The Berimbau Page at Rhythmweb

- Berimbau by Richard P. Graham and N. Scott Robinson

- YouTube video, free-improvised berimbau solo by Greg Burrows

- Beat! Percussion Fever. "Berimbau"