Belle of Oregon City

The Belle of Oregon City, generally referred to as Belle, was built in 1853, and was the first iron steamboat built on the west coast of North America.[2]

_ad_Feb_1855.jpg) Advertisement for steamers Belle and Mary, February 17, 1855 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Belle of Oregon City |

| Owner: | Wells and Williams; Oregon Steam Navigation Company[1] |

| Port of registry: | [1] |

| Route: | lower Columbia River, lower Willamette River |

| Builder: | William H. Troup and ironworks of Thomas V. Smith[2][3] |

| Launched: | August 18, 1853, Linn City, Oregon[1][3] |

| In service: | 1853 |

| Out of service: | 1869 |

| Fate: | Dismantled 1869, engines salvaged[1] |

| Notes: | First iron vessel built in Oregon or the Washington Territory; first steam vessel with Oregon-built equipment.[2] |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | shallow draft inland passenger/freight, iron hull[2] |

| Tonnage: | 54 gross[2] |

| Length: | 90 ft (27 m) on keel; 96 ft (29 m) measured over guards[1][2] |

| Beam: | 16 ft (5 m)[3][4] |

| Depth: | 4.0 ft (1 m) depth of hold[1] |

| Installed power: | steam engine |

| Propulsion: | sidewheels |

Design and construction

Belle was also the first steamboat to be powered by machinery built entirely in Oregon. All the iron and all the required machinery, including the boiler and steam engines, was produced by foundryman Thomas V. Smith in his ironworks at Oregon City.

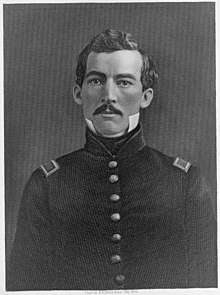

Capt. William H. Troup (1827-1882).[5] built the vessel for two other men, Capt. William B. Wells (1822-1863)[6] and Capt. Richard Williams(1830-1898).[7]. Because of her iron hull, she was much more durable than most early Oregon steamboats, lasting until 1869. Belle measured 90 ft (27 m) on her keel and 96 ft (29 m) measured over her guards.[2]

Operations

.jpg)

Williams and Wells first used Belle on the Willamette River run between Portland and Oregon City, with passenger fares $2 each way. The boat departed the base at Willamette Falls at 7:30 a.m., was at the Oregon City dock by 8:00 a.m., stopping at Milwaukie at 8:30 a.m., and reached Portland at 9:30 a.m.

At 2:00 p.m. Belle steamed back upriver, reaching the falls by 4:00 p.m. (Because of a stretch of shallow water on the Willamette near the mouth of the Clackamas River known as the Clackamas Rapids, only smaller vessels could make this run.) Belle also ran on the Cowlitz River and to Fort Vancouver.[2]

By July 1855, Belle was on the route from Portland down the Willamette and then also ran up the Columbia to the lower Cascades, making three runs a week, under Captain Wells, with J.M. Gilman as engineer and N.B. Ingalls as purser. (Ingalls would become one of the longest-serving pursers on the Columbia River, serving on many of the river steamers from the 1850s to his retirement in 1893).

Passengers headed up river would disembark at the lower Cascades, travel on the portage road along the north bank, and then board the sidewheeler Mary upriver to the next head of navigation, The Dalles. Freight charges were high, $50 a ton on cargo from Portland to The Dalles, but Belle and Mary still could not handle the demand, and other steamers came on the routes, driving rates down to $30 a ton.[2][3][8]

Military transport

In the 1850s, the U.S. Army was engaged in forcing the First Nations to cede their dominion over the vast lands of the Oregon and Washington Territories and move onto reservations.

The army maintained posts at Fort Vancouver, the Cascades, and The Dalles. In late 1855 orders arrived to move the army's main base up from the Cascades to the Dalles, closer to the anticipated area of war operations in the next campaign season. Movement on the river was completely halted by the severe winter in January 1856, when the Columbia froze from bank to bank from the Gorge on down well below the mouth of the Willamette. No river traffic moved anywhere on the river, even down to Astoria, Oregon. When the river was finally clear enough of ice, Belle and another boat, the Fashion started moving the Army's equipment up from Fort Vancouver.[2]

On March 26, 1856, a war party of the First Nations attacked the town at Upper Cascades, burned most the buildings, and laid siege to the blockhouse at Fort Cascades, killing 11 civilians and 3 soldiers. Word soon reached Fort Vancouver, where Lt. (later Genl.) Philip H. Sheridan loaded his troopers on Belle and steamed upriver to the Cascades. Meanwhile, other troops were coming downriver on Mary from The Dalles, and arrived at Upper Cascades.

There was some fighting for a few days around the lower Cascades, during which Belle acted as ammunition and supply transport. Due to military blunders the troops were not able to trap the First Nations war party at the Upper Cascades; they slipped back into the forest.[2]

Later years of service

When the Oregon Steam Navigation Company was formed, Belle was absorbed into the monopoly and became part of O.S.N.'s near-absolute dominance of Columbia River steam navigation, but was little used by the new company. Her sturdy construction still allowed her to outlast most of the steamboats built on the Willamette and Columbia Rivers in the 1850s and 1860s. Belle was scrapped in 1869, her hull was dismantled and shipped to China, and her engines went to power a sawmill at Oak Point.[2][3]

Notes

- Affleck, Edward L., A Century of Paddlewheelers in the Pacific Northwest, the Yukon, and Alaska, Alexander Nicholls Press, Vancouver, BC 2000 ISBN 0-920034-08-X

- Mills, Randall V., Sternwheelers up Columbia – A Century of Steamboating in the Oregon Country, Univ. of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE (1977 reprint of 1947 ed.). pp. 25-26, 31-40,165, 170, 190. ISBN 0-8032-5874-7

- Wright, E.W. ed,, Lewis & Dryden Marine History of the Pacific Northwest, at 43-44 , Lewis & Dryden Printing Co., Portland, OR 1895

- Mills gives beam as 26 ft (8 m)

- "Capt William Henry Troup". Find a Grave. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- "CPT William B. Wells". Find a Grave. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- "Richard Williams". Find a Grave. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Timmen, Fritz, Blow for the Landing – A Hundred Years of Steam Navigation on the Waters of the West, Caxton Printers, Caldwell, ID (1973). pp. 8, 14, 72-73. ISBN 0-87004-221-1

Further references

- "Sheridan's First Fight --The Indian Repulse at the Upper Cascades of the Columbia", New York Times, June 5, 1888 (reprinted from the Portland Oregonian May 29, 1888)

- Wilma, David. "Native Americans attack Americans at the Cascades of the Columbia on March 26, 1856", HistoryLink.org Essay 5190 February 07, 2003 (revised April 16, 2007)

- Lewis and Clark's Columbia River - Fort Cascades