Belle Île

Belle-Île, Belle-Île-en-Mer, or Belle Isle (ar Gerveur in Modern Breton; Guedel in Old Breton) is a French island off the coast of Brittany in the département of Morbihan, and the largest of Brittany's islands. It is 14 kilometres (8.7 miles) from the Quiberon peninsula.

Red dot: Location of the city Le Palais on Belle Île.

Administratively, the island is divided into four communes:

Belle-Île formed a canton until 2015 when it was merged into Quiberon as part of a general overhaul.

Geography

The island measures 17 by 9 kilometres (10.6 by 5.6 miles) and has an average altitude of 40 metres (130 feet). The area is about 84 square kilometres (32 square miles). The coasts are a mixture between dangerously sharp cliff edges on the southwest side, the Côte Sauvage ('wild coast'), and placid beaches, the largest being les Grands Sables ('the great sands') and navigable harbours on the northeast side. The island's climate is oceanic, having less rain and milder winters than on the mainland.

The two main ports are Le Palais (accessible by ferry from Quiberon, Port-Navalo and Vannes) and Sauzon (accessible by ferry from Quiberon and Lorient).

There used to be forests on the island, but these have long disappeared due to increasing agricultural use of the land.

Climate

| Climate data for Belle Île (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.5 (58.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

21.5 (70.7) |

25.0 (77.0) |

28.2 (82.8) |

34.8 (94.6) |

33.8 (92.8) |

33.4 (92.1) |

29.9 (85.8) |

24.8 (76.6) |

19.2 (66.6) |

16.0 (60.8) |

34.8 (94.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.7 (49.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.4 (52.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

19.1 (66.4) |

21.1 (70.0) |

21.4 (70.5) |

19.7 (67.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

10.6 (51.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 7.9 (46.2) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.1 (48.4) |

10.7 (51.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.1 (64.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

16.8 (62.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

10.9 (51.6) |

8.6 (47.5) |

12.7 (54.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 6.0 (42.8) |

5.5 (41.9) |

6.9 (44.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

13.3 (55.9) |

15.1 (59.2) |

15.3 (59.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

12.0 (53.6) |

8.9 (48.0) |

6.7 (44.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.0 (14.0) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

3.0 (37.4) |

5.4 (41.7) |

8.2 (46.8) |

7.4 (45.3) |

6.6 (43.9) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 82.0 (3.23) |

60.9 (2.40) |

54.3 (2.14) |

50.4 (1.98) |

52.2 (2.06) |

32.4 (1.28) |

38.3 (1.51) |

33.5 (1.32) |

56.3 (2.22) |

77.7 (3.06) |

78.4 (3.09) |

85.0 (3.35) |

701.4 (27.61) |

| Average precipitation days | 12.9 | 9.7 | 10.0 | 9.4 | 9.1 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 5.9 | 7.8 | 12.4 | 13.4 | 13.5 | 117.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 88 | 88 | 85 | 85 | 86 | 85 | 85 | 86 | 86 | 88 | 86 | 88 | 86.3 |

| Source 1: Meteo France[1][2] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Infoclimat.fr (humidity, 1961–1990)[3] | |||||||||||||

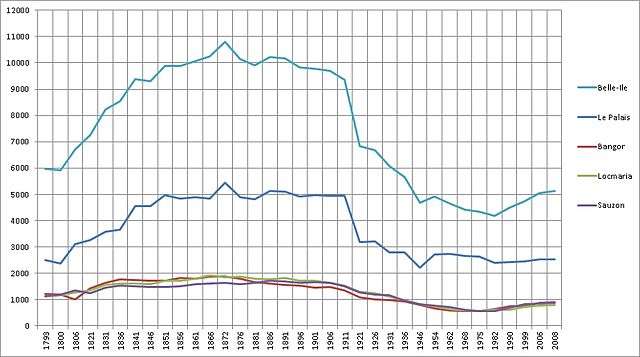

Demography

At the 2009 census, the population of Belle Île was 4,920. However, in summer the population may increase to 25,000, with a peak at 35,000 between 15 July and 15 August due to tourist activity.

History

Belle Île was separated from the mainland about 6000 BC, earlier than the neighbouring islands of Houat and Hœdic. Archaeological finds from the Bronze Age suggest that the island enjoyed a large increase in population in this time, probably due to improvements in seafaring. It was then a naval base for the Veneti (Gaul).

The Roman name of the island seems to have been Vindilis, which in the Middle Ages became corrupted to Guedel.[6] During the ninth century Belle-Île belonged to the county of Cornouaille. In 1572 the monks of the abbey of Ste Croix at Quimperlé ceded the island to the Retz family, in whose favour it was raised to a marquisate in the following year. It subsequently came into the hands of the family of Fouquet. The island's fortifications were erected by Vauban on behalf of Nicolas Fouquet, prior to Fouquet incurring the displeasure of Louis XIV; the land was ceded to the crown in 1718.[6]

Seven Years War

The island was held by British troops from 1761, following its capture by an expedition sent out from England, to 1763, when it was returned to France in exchange for Menorca as part of the Peace of Paris. Because of the upheaval from the conflict, half the population had moved back to the mainland and the abandoned lands were offered to the deported Acadians who settled here in 1766.

The attacks on Belle Île and siege of Belle Île have been described by Olaudah Equiano (ca. 1745-ca. 1797) in his autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African, 1789, June 1792.[7] His book was a bestseller in his own time. He became a central figure in the British abolitionist movement, as a forceful abolitionist lecturer, based on his own experiences as a former slave. Equiano gave a detailed eyewitness report of the attacks and siege.

Much of the island's current population is descended from repatriated Acadian colonists who returned to France after being expelled from Acadia during the Expulsion of the Acadians.

Today, Belle-Île's population is about 5,300, and its economy is largely dependent on tourism and fishing.

Culture

During the summer the island's population increases dramatically, as many people own a second home on the island due to its secluded location and beaches.

Lyrique en Mer/Festival de Belle Île[8] is the largest opera festival in western France. Founded in 1998 by American opera singer Richard Cowan, the festival produces two staged operas every summer, conducted by Music Director Philip Walsh and directed by Mr. Cowan, the Artistic Director. Additionally, there are sacred concerts in all four of the island's historic churches, as well as many smaller concerts and Master Classes. Lyrique en Mer has wide support from the French business community as well as from the Conseil Général, the Conseil Régional.

Depictions

The island has been a popular location for artists. Octave Penguilly L'Haridon's 1859 painting Les Petites mouettes ("Little Gulls") (1858, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rennes) depicts the island. It was praised by Maxime Du Camp and Charles Baudelaire, who referred to the sense of the uncanny, as though the rocks make "a portal open to infinity...a wound of white birds, and the solitude!"[9] During the 1870s and 1880s, French Impressionist painter Claude Monet painted the rock formations at Belle Île. Monet's series of paintings of the rocks at Belle Île astounded the Paris art world when he first exhibited them in 1887.[10][11] Most notable are the Storm, Coast at Belle-Ile and Cliffs at Belle-Ile both rendered in 1886. The first time Auguste Rodin saw the ocean off the Brittany coast he exclaimed, “It’s a Monet."

Australian born artist John Russell was a man of means and having married a beautiful Italian, Mariana Antoinetta Matiocco, he settled at Belle Île off the coast of Brittany where he established an artists' colony. Russell had met Vincent van Gogh in Paris and formed a friendship with him.[12] Van Gogh spoke highly of Russell's work, and after his first summer in Arles in 1888 he sent twelve drawings of his paintings to Russell, to inform him about the progress of his work. Monet often worked with Russell at Belle Île and influenced his style, though it has been said that Monet preferred some of Russell's Belle Île seascapes to his own. Russell did not attempt to make his pictures known.

In 1897 and 1898 Henri Matisse visited Belle Île. Russell introduced him to impressionism and to the work of Van Gogh (who was relatively unknown at the time). Matisse's style changed radically, and he would later say "Russell was my teacher, and Russell explained colour theory to me."[13]

The island is the setting for portions of the novel The Vicomte of Bragelonne: Ten Years Later, Alexandre Dumas, père's second sequel to The Three Musketeers. Dumas has his character Aramis fortify the island (in place of Vauban, historically) and Porthos dies there, in the caves of Locmaria.

Notable People

- Laurent Voulzy made the island famous with his song "Belle-Île en Mer - Marie Galante" (1985).

See also

References

- "Données climatiques de la station de Paris" (in French). Meteo France. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- "Climat Bretagne". Meteo France. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- "Normes et records 1961-1990: Belle Ile-Le Talut (56) - altitude 37m" (in French). Infoclimat. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- (in French) http://cassini.ehess.fr/ Population before 1962 Census

- http://www.insee.fr/fr/ppp/bases-de-donnees/recensement/populations-legales/default.asp INSEE Legal polulations in 2008

-

- Dover Thrift Editions, Dover 0-486-40661-X, Chapter IV

- (in English) ((in French)) Lyrique-en-mer Archived March 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Festival official website

- Steven Z. Levine, Monet, Narcissus, and Self-Reflection: The Modernist Myth of the Self, University of Chicago Press, 1995, p.62.

- Art Gallery of New South Wales: Belle Île

- Belle-Ile: Monet, Russell and Matisse in Brittany - Art Gallery of New South Wales - Absolutearts.com

- Ronald Pickvance, Van Gogh In Saint-Remy and Auvers, pp. 62-63, Exhibition catalog, Published: Metropolitan Museum of Art 1986, ISBN 0-87099-477-8

- The Unknown Matisse..., ABC Radio National, 8 June 2005

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Belle-Île-en-Mer. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Belle Île. |

- (in English, French, and German) Tourist office website

- (in English) Belle-Ile visit: more than 300 photos of beaches, creeks, coves, rocks, flowers, etc.

- (in English) Le Palais

- (in English) Sauzon

- KAERILIS, Belle-Isle Whisky Specialties