Beaupré Hall

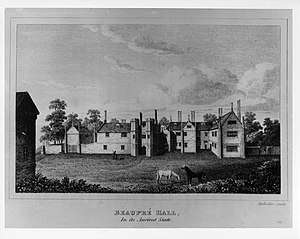

Beaupré Hall was a large 16th-century house mainly of brick, which was built by the Beaupres in Outwell, Norfolk, England and enlarged by their successors the Bells.[1] Like many of Britain's country houses it was demolished in the mid-20th century.

| Beaupre Hall | |

|---|---|

Beaupre Hall, Outwell, Norfolk, | |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | country house |

| Architectural style | Medieval, Turreted Gate house |

| Location | King's Lynn and West Norfolk, East of England, Norfolk |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 52.61720°N 0.23343°E |

| Opened | Built around 1500 enlarged until 1740, Demolished 1966 |

| Technical details | |

| Material | stone and slate roof |

History of the Hall

The history of the Hall begins with its family origins, a Norman from Saint-Omer who dwelled and, according to Christopher Hussey "christened his domain with gallic grace, among the dull-sounding names of the danes."[2]

The knight of St Omer (de Beau-pré) accompanied William the Conqueror's invasion of England; he "appears in the Roll of Battle Abbey, and his descendants lived here in their place of Beaupré."[2]

Several other noted members of the St Omer family are Sir Hugh de St Omer and John de St Omer, who according to the chronographer Matthew Paris, were known to have 'penned a counterblast' to a monk of Peterborough who had lampooned the people of Norfolk during the reign of King John; which elevated them to literary fame.[2]

A Sir Thomas de St Omer was keeper of the wardrobe to King Henry III. His successor William de St Omer was granted a fair at Brundale and at Mulbarton, Norfolk, in 1254, where his arms (a fess between six cross-crosslets) could formerly be seen on a monument in the church. Mulbarton came to Sir William Hoo (1335-1410) through his marriage to Alice de St Omer (died c. 1375), daughter of a later Thomas de St Omer and Petronilla de Malmaynes. Sir William Hoo added to heraldic glass which they placed in the chancel windows, and (after a second marriage) was buried there beside Alice.[3][4] His grandson Thomas Hoo, Baron Hoo and Hastings (c. 1396-1455) bore the St Omer arms quartered with Hoo.[5][6][7]

- Beaupré

Christian, daughter and coheir of Thomas de St Omer, married John, the great-great-grandson of one Synulph, who lived during the reign of King Henry II, and had issue: John dicte quoque Beaupré,[8] who lived during the reign of King Edward II, and married Katherine, daughter of Osbert Mountfort. Their son Thomas Beaupré would be raised by his grandmother Christian (last St Omer in this line) after the death of both of his parents. Thomas was knighted by King Edward III, and married Joan Holbeache, and died during the reign of King Richard II.

Generations later the Hall was in the possession of Edmonde Beaupré. After his death in 1567 leaving no male heirs, the hall succeeded to Sir Robert Bell, by virtue of marriage to Edmonde's daughter Dorothie in 1559; whereby his Beaupré line became extinct.[2]

Upon Sir Robert Bell's passing following the events of the Black Assize of Oxford, in 1577, the hall passed to his son Edmonde, and his heirs successively until finally in 1741, Beaupré Bell bequeathed the hall to his sister who married William Greaves, of Fulbourn.

Their daughter Jane brought it by marriage to the Townley family, who held Beaupré Hall until it passed into the hands of Edward Fordham Newling, and his brother.[2]

Construction and architecture

Phase I (1500–1530) Main construction of the Hall was carried out during the lives of Nicholas Beaupré and his wife Margaret Fodringey. A number of successive enlargements in the end consisted of over thirty interior rooms. The Hall, emerging from the South-West end, stretched North-East, with an additional wing branching out North-West, at an angle to make a chapel. These structures date from the early 16th century and had corners that were fortified with semi-Gothic spirelets, that were also added to later additions throughout the years.[2]

Phase II (1531–1570) A turreted gatehouse was added c. 1530, and placed in front of the entry facing South-East. This structure was built upon an old model, probably by Edmonde Beaupré during the time of his marriage with Margaret the daughter of Sir John Wiseman, servant to the 15th Earl of Oxford. His second wife, Katherine Wynter (widow of John Wynter of Great Yarmouth*)[9] was the daughter of Phillip Bedingfeld of Ditchingham Hall.

Phase III (1571–1577) After Edmonde Beaupre's death in 1567, the hall was enlarged by the Bells: new construction and renovations included:

Demolishing and rebuilding the body of east wing of the old house (where the living quarters were located).

Refitting the north-east section with porches on each side which had upper levels, and bays in front. From this section a large wing was added spanning south-east (demolished c. 1850), and a small wall was built connecting the wing to the north-east section of the gate house, which effectively enclosed the area to make a courtyard.

Around 1570, the south west end of the Gate House was fitted with a new building that connected a gated section of wall to the south-west wing, making another courtyard. This wing spanned north-west to the main block, and from the main block extended the chapel, which had an altarpiece in the far north-west end.

Phase IV (1577-1935) Aside from several rooms on the first floor and the main door which had 16th-century linenfold paneling, the Hall was variously altered internally by its successors (some negligent) from the 16th century. These alterations included a 17th-century fireplace, Georgian Wainscoting, and other 18th-century paneling. Despite further unfortunate alterations to the back of the Hall during the 19th century, by the early 20th century the Hall was not inhabited and what was left of the building was mostly a ruin.[2][10][11]

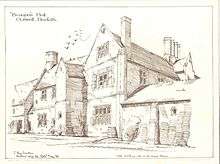

Gate House and heraldry

The Gate House was built around 1525, and was rebuilt and fortified until the time of Edmonde Bell.

The entry had four-centred arches connected to four towers built mostly of brick with stone dressings and upper caps made of ashlar. The second floor of the Gate House was a drawing room, lit by square-headed windows decorated with stone mullions and transom, and fitted with a fine Elizabethan fireplace, which had a marble frame and carved wood overmantel that enclosed the fireplace from the floor to the ceiling and had early Jacobean architecture style paneling with a pair of trimmed arches that were encased and separated by ornate columns, directly above the center of the marble arch frame. Each trimmed arch panel displayed a heraldic relief carving:

The Arms as they appeared on the left or north-west side of the mantelpiece featured the Arms borne by Bell. A Jacobean style pillar, separated this coat and arch from the other where appeared the quartered and impaled Arms of Beaupre: From the sinister top appear the quarters of Edmonde Beaupre/St Omer-Fodringhay/ and Baulney Bottom: Dorewood-Coggeshall-and Harske.

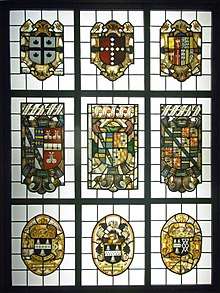

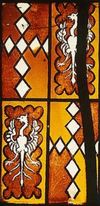

The matrimonial landmarks of the family are recorded in beautiful heraldic glass panels that date from 1570. The Beaupré panels are slightly larger and older than the Bell panels; throughout the mantling is particularly fine.

The following coats occur and have been blazoned accordingly:[2]

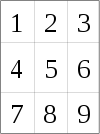

1

Inscribed in Latin: Arma Willi(el)m(i) Coggeshall Militis ("arms of William Coggeshall, Knight")

Top Left Frame: Argent, a cross between four escallops sable (Coggeshall) Sir William Coggeshall (1358–1426), High Sheriff of Essex, who married Antiocha Hawkwood, daughter of Sir John Hawkwood.[12]

2

Top Center Frame: Quarterly or and gules, a cross lozengy argent (Fotheringhay[13]) (here shown as Gules, a cross lozengy argent) Thomas Fotheringhay

3

Fotheringhay/Fodringhay[14] quartering Lyndsey[15] (Gules, an eagle displayed argent a bordure engrailed or) impaling quarterly of 6: 1: Ermine, on a chevron sable three crescents or (Dorewod of Dorewoods Hall, Bocking, Essex); 2:Coggeshall; 3: Harske/Harsick,[16] Or a Chief indented Sable; 4:Coggeshall; 5:Harske; 6:Dorewod)

Thomas Fodringhay married Elizabeth Dorward, daughter and heiress of William Dorward (by his wife Mary Harsick, a daughter and co-heiress of Roger Harsick), 2nd son of John Doreward (died 1420), Speaker of the House of Commons, by his wife Blanche Coggeshall, daughter and heiress of Sir William Coggeshall.[17]

4

Inscribed in Latin: Thomas de Beauspre Armiger cepit in uxorem Margareta(m) filia(m) Joh(ann)is Meris Armigeri) ("Thomas de Beaupre, Esquire, took as his wife Margaret daughter of John Meeres, Esquire"[18])

Center Left Frame: The Arms of Thomas Beaupré, Quarterly - 1 & 4: Argent, on a bend azure three cross crosslets or (Beaupré); 2 & 3: Azure, a fess between six cross crosslets or (St Omer), impaling the arms of his wife Margaret Meeres/de Meris, daughter of John Meeres (d.1471), Gules, a fess between three water bougets ermine (Meeres).[19]

This is the family descended from Roger de Meres (d.1385) (alias de Kirton/Kirketon), of Kirton Meres in Lincolnshire, a King's Sergeant 1367, and a Justice of the Common Pleas in 1371.[20][21]

5

Inscribed above in Latin: Nich(olae)us de Beaupré cepit in uxorem Margaretam uniam filiam et heredu Thome Fodringaye Armiger ("Nicholas de Beaupré took as his wife Margaret, one of the daughters and heiress of Thomas Fodringaye, Esquire")

Center Frame: Beaupré quartering St Omer impaling, quarterly of 4: 1st & 4th grand quarters: Fotheringhay quartering Lyndsey; 2nd & 3rd grand quarters: quarterly of 6: 1:Dorewod; 2:Coggeshall; 3:Harske/Harsick; 4:Coggeshall; 5:Harske/Harsick; 6:Dorewod;

Nicholas Beaupré married Margaret Fodringaye, one of the three daughters and heiresses of Thomas Fodringaye (son of Gerrard Fodringaye) by his wife Elizabeth Dorward, sister and heiress of John Dorward and daughter of William Dorward of Bocking, Essex. One of Margaret's sisters was Christiana Fodringaye, wife of John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford, (1482-1540), KG, Lord Great Chamberlain.[14]

6

Inscribed above in Latin: G(eral)dus (?) de Bellapré filius et heres dict(i) Nich(ola)i Bellispré et Margarete... ("Gerald de Beaupré, son and heir of the said Nichholas Beaupré and Margaret...")

Center right frame: Quarterly of 4: 1st & 4th grand quarters: Beaupré quartering St Omer; 2nd & 3rd grand quarters: quarterly of 4: 1st & 4th grand quarters: Fotheringhay quartering Lyndsey; 2nd & 3rd grand quarters: quarterly of 6: 1:Dorewod; 2:Coggeshall; 3:Harske/Harsick; 4:Coggeshall; 5:Harske/Harsick; 6:Dorewod;

7

Bottom Left Frame: Sable a Fess Ermine between three church Bells Argent (Bell); Inscribed "Bell A(nn)o 1577"

8

Bottom Center Frame: Arms of Sir Robert Bell.

9

Bottom Right Frame: Bell impaling Harington, Sable a fret Argent.

Final years

During World War II, Beaupré Hall was used by the RAF. From this point, the Hall fell into a state of further disrepair until its demolition in 1966. During the 1950s, the grounds of the hall and the barrack huts that had been erected by the RAF were used to house students on the 'Holidays With Pay' scheme run by the government. In the book, The Bedside Companion for Ghosthunters by Ingrid Pitt, there is an account of a ghost seen by a couple of students who entered the Hall at night; legends of headless horsemen and other spirits roaming the hall have also been reported.

Notes

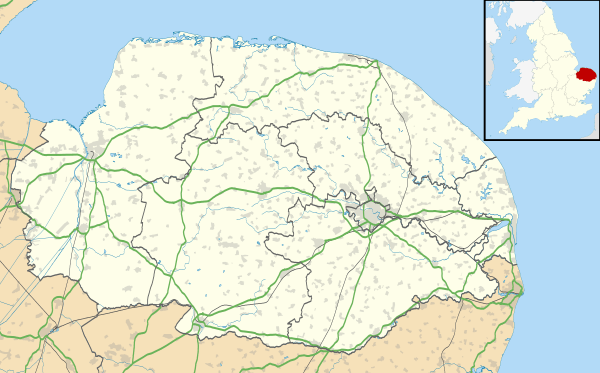

- grid reference TF513045 - shown on this map from c. 1890.

- Hussey, C., "Beaupré Hall Wisbech, Coventry" Homes and Gardens Old & New, (Country Life), 1923

- W.D. Cooper, 'The families of Braose of Chesworth, and Hoo', Sussex Archaeological Collections VIII (London 1856), pp. 97-131, and pedigree at pp. 130-31 (Internet Archive).

- F. Blomefield, ed. C. Parkin, An Essay Towards a Topographical History of the County of Norfolk, Revised edition, Vol. V (William Miller, London 1806), at pp. 75-79; see also Vol. VII (1807), pp. 219-21 (Hathi Trust).

- J.E. Ray, 'The parish church of All Saints, Herstmonceux, and the Dacre tomb', Sussex Archaeological Collections LVIII (1916), pp. 21-64, at pp. 36-55 (Internet Archive).

- G. Elliott, 'A monumental palimpsest: the Dacre tomb in Herstmonceux church', Sussex Archaeological Collections 148 (2010), pp 129-44. (Read at thekeep.info pdf).

- L.L. Williams, 'A Rouen Book of Hours of the Sarum Use, c. 1444, belonging to Thomas, Lord Hoo, Chancellor of Normandy and France', Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Vol. LXXV (1975), pp. 189-212 (Jstor - Sign-in required).

- "Also called Beaupré".

- Bell, R. R.L., Tudor Bell's Sound Out, pb., 2006. p. 175-6-7

- A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume IV

- Worsley, G., England's Lost Houses, Aurum Press Limited, 2002

- Josselyn, J. H., Sir John Hawkwood, the Condottiere, some of his lineal descendants, Notes and Queries, 7th series, Vol. X, London, 1890, p. 101-102

- Robson, Thomas, The British Herald, Volume 1

- See pedigree of Fodringhay, Heraldic Visitation of Essex, 1558, p.52

- see arms of Lyndsey (Gules, an eagle displayed argent a bordure engrailed or) blasoned in pedigree of Thursby, with quarterings of Fodringhay, Dorewod, Harsick, Coggeshall, etc., Heraldic Visitation of Essex, 1558,p.298; not apparently the arms of Baulney

- Pedigree of Fodringhay, Heraldic Visitation of Essex, 1558, p.52

- Pedigree of Dorward, Heraldic Visitation of Essex, 1558, p.104

- See detailed image

- As carved on a bench-end in Kirton Church in Lincolnshire (Edward Deacon)

- Foss, Judges of England: "Roger de Meres was of a Lincolnshire family, established at Kirketon in the district of Holland"

- Edward Deacon, The descent of the family of Deacon of Elstowe and London, with some genealogical, biographical and topographical notes, and sketches of allied families including Reynes of Clifton, and Meres of Kirton, p.18