Battle of Turner's Falls

The Battle of Turner's Falls or Battle of Great Falls; also known as the Peskeompscut massacre or the "Wissantinnewag massacre", was fought on May 19, 1676, during King Philip's War, in present-day Gill, Massachusetts, near a falls on the Connecticut River. The site is across the river from the village of Turners Falls. This was one of the most important conflicts of King Philip's War, as it marked a turning point in the conflict that would eventually lead to the war's end.

A largely untrained, inexperienced militia force of 150-160 engaged in an initial massacre and looting of the Peskeompskut camp, killing around 100-200 people. Conducting a fighting withdrawal after the counterattack through ambushes set by the Algonquian tribe's outnumbered warriors, resulting in the deaths of 38 militiamen (including William Turner †) and the wounding of an unknown number.

Background

Wissantinnewag-Peskeompskut was an established annual fishing encampment along the Connecticut River, where some land had been cleared of dense woods for spring planting and other land leveled to accommodate wetus (domed huts used by Algonquins) on around 300 acres of choice land.10 At least twice yearly, for thousands of years, People came to Peskeompskut to fish, plant, and harvest food for the year.1,2 The Spring of 1676 found this ancestral fishing and planting place more busy than was usual, as King Philip's War had displaced many from the south and access to food in other areas controlled by the Nipmuc had been destroyed in the conflict. By mid-May 1676, warriors and families of Nipmuc, Narragansett, Wampanoag and Pocumtuc warriors gathered for the fishing runs. As King Philip's War was ongoing, this year three camps were established. One camp was downriver from the main camp and closer to the conflict areas on what is now “Sneed’s Island”: most of the warriors stayed in that camp. The main camp had women, children, elderly and those focused on farming & fishing. Another camp was across the river from that camp.8

By mid-May, 1676, peace talks between the Colony of Connecticut and the Narragansett were in the early stages, with some prisoner releases being made to establish good faith. Some of these releases included those who had been taken captive during an earlier raid on Hatfield. The Connecticut War Council directed the northernmost settlers in Hatfied, Hadley and Northampton to take no aggressive action and also recalled the army under Major Savage. They also recalled a large part of Captain William Turner's company, leaving him with “a company of single men, boys and servants”.8 While the presence of those troops during the winter had caused shortages, the reduction of military support caused concern amongst the settlers.1 This concern was amplified by the large and growing encampment of Nipmuc and others around the falls.1

On May 13th, 1676, some of the warriors camped in Peskeompskut raided nearby farms and carried off 70 cattle and horses.1,8 Two days later, some of the recently released gave a detailed accounting of the encampment, the fenced cattle area and other intelligence to the local leaders. The settlers resolved to act without the approval of the Connecticut War Council. Captain William Turner and his Lieutenant Samual Holyoke gathered together a company of volunteers from the nearby river towns and prepared to attack the encampment.

Prelude

On May 18, 1676, there was an uncommon feast of beef and milk from the Hatfield raid to accompany the staple salmon at Peskeompskut.8 After dinner, the warriors returned to their camp leaving the main camp unguarded. To the south, Captain Turner, the remains of his soldiers and settlers from the northernmost towns gathered in Hatfield with the purpose of attacking the encampment at Peskeompskut. They were a largely untrained, inexperienced militia force who were planning on attacking a seasoned group of 60-70 warriors in their own territory. They banked on the numerical advantage, over 160 men, and the element of surprise to make up the difference.

They left on horseback after nightfall, riding through a thunderstorm, which may have occluded them from posted Nipmuc sentries. They also crossed the Connecticut River “at the mouth of Sheldon’s brook” to avoid the sentries at the usual place of crossing.1,12 They crossed the Green River “at the mouth of the Ash Swamp brook to the east, skirting the great swamp” 1,8. Captain Turner and his men found themselves on a high land just south of Mount Adams overlooking Peskeompskut in the predawn hours of May 19, 1676. Leaving their horses, they walked down to the encampment. They arranged a signal to begin firing and then advanced into the encampment. They were able to get within point-blank range of the wetus.

Engagement

At dawn, the signal was given and Captain Turner's men began firing into the wetus, some through the exits to insure no escape. “A great and notable slaughter” ensued.10 Those not killed in the initial fusillade ran away from the men towards the Connecticut River, attempting to cross by canoe or by swimming. Some were heard to yell “Mohawk! Mohawk!” as they fled. The canoes were soon overfilled with the desperate.

Captain Turner's men lined up along the shoreline and opened fire on both the swimmers and those in the canoes.1 Some of those not killed by bullets were swept over the falls; others found refuge under overhanging rocks but were also found and killed. “Captain Holyoke killing five, young and old, with his own Hands from under a bank.”5 He was also credited with “killing four native children with one swipe of his sword”. 9 A survivor reported that “shot came as thick as rain”. 1 Reportedly, over 100 were dead on the shore and around 130 perished in the river. None of Captain Turner's men were killed by return fire, though one man died as he emerged from a wetu and was shot by friends who thought him a native.5,8

Even though he knew that there were likely warriors around, Captain Turner ordered the destruction of the camp. They burned all the wetus and their contents.8 They destroyed the stores of dried or smoked fish. They found two blacksmith forges and tools for fixing arms and bullets; they took the blacksmith tools and threw them into the river.8 They plundered what they could carry and3 freed an English captive, who informed them that King Philip and 1000 warriors were nearby. Around the time of this disclosure, the warriors who had camped elsewhere began a concerted counterattack. An immediate retreat was ordered.1

Once mounted, Captain Turner and his men retreated along the westerly route that they had come but without the cover of darkness or thunderstorm that had helped them in their approach. Surviving Peskeompskut warriors harried the rear of the company, whilst other warriors from encampments to the south of Peskeompskut laid an ambush near White Ash Swamp.1 When the force rode near White Ash Swamp, they were attacked from all sides. The command structure and discipline immediately dissolved in the inexperienced, largely citizen militia. The group separated into 3-5 smaller groups, with most of the soldiers following Captain Turner's force heading directly for another ambush at Green River Ford.1

The narrow valley leading to Green River Ford was well known as being ideal for ambush. “in a dangerous Passe, which they were not sufficiently aware of, the skulking Indians, killed at one Volley, the said Captain and Eight and Thirty of his Men; but immediately after they had discharged, they fled”3. Warriors ambushed the company there and Captain Turner was shot through the thigh and back as he crossed the river.10 Samuel Holyoke, took command and organized a retreat to Hatfield that lost no men.

Reverend Hope Atherton[1] [2][3] got separated from the main body and had to find their way alone; a few were successful while others never returned.

Aftermath

Captain Turner's body lay in the river for several days until it was recovered. Of the 160 men who attacked Peskeomskut, 38 were killed outright in the retreat or tortured to death (nearly a quarter of his men), six were missing (later found) and many had wounds that shortened their lives. On May 30th, 1676, 250 surviving warriors from Peskeompskut attacked Hatfield. Though their attack was repulsed, 5 settlers were killed, 20 houses and barns were burned, many cattle were killed, sheep were driven away, and a number of houses & shops looted.12 In June, English scouts found places where Captain Turner's captured men were tortured and burned. 12

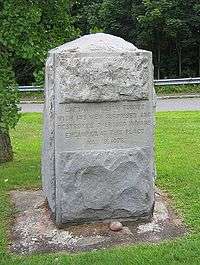

The falls where this occurred were later named “Turner’s Falls”. In 1736, a grant was made to the descendants of the “Falls Fight” of land near the conflict (currently the town of Bernardson). “The village of Riverside, in Gill, is supposed to occupy the spot where the fight took place, and in that village a grove used by picnic parties is said to mark the precise locality of Capt. Turner's first attack upon the Indian camp”.6 The site of the battle is in the Riverside Archeological District, a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

There is an extensive account of the battle and the colonists' reasons for attacking contained in a book authored by George Madison Bodge and reprinted by the Genealogical Publishing Company in 1967. The account includes a description of the battle, a listing of many of the soldiers who fought with the colonists, the soldiers who were slain in the battle, and soldiers or their descendants who were entitled to land due to their participation in the battle.

References

1 McBride, K. (2016) Battle of Great Falls/ Wissatinnewag- Peskeompskut (May 19, 1676) Department of the Interior 2 Remembering and Reconnecting: Nipmucs and the Massacre at Great Falls. A Narrative, Chaubunagungamaug Nipmuck Historic Preservation Office and Associates for the Battle of Great Falls/ Wissatinnewag-Peskeompskut Pre-Inventory Research and Documentation Project October 2015. 3Schultz, Eric; Tougias, Michael (1999). King Philip's War. Woodstock, VT: The Countryman Press. 4 A New and Further Narrative of the State of New-England; being a Continued Account of the Bloudy Indian War. From March till August 1676, London, 1867 5 Sheldon, G. (1895) The History of Deerfield, Vol. I, pp. 155–157. 6 Everts, L. (1879) History of the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts, Volume II 7 Easton, J. (1913) Narratives of the Indian Wars, 1675-1699 . New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 8 Soldiers in the King Philip's War pg. 250–265. 9 Evans, E. Shameful massacre by Capt. Turner Greenfield Recorder, 10/17/2016 10 Mather, I. (1676) A Brief History of the War with the Indians in New England. 11Hubbard, W. (1677) A Narrative of the Troubles with the Inidans in New England. 12 Judd, S. and Boltwood, L. History of Hadley, Metcalf, Amherst, MA 1863. 13 George Madison Bodge, Soldiers in King Philip's War, Being a Critical Account of that War,' Third Edition', Genealogical Publishing Company, Baltimore, 1967.