Nipmuc

The Nipmuc or Nipmuck people are descendants of the indigenous Algonquian peoples of Nippenet, 'the freshwater pond place', which corresponds to central Massachusetts and immediately adjacent portions of Connecticut and Rhode Island. The tribe were first encountered by Europeans in 1630, when John Acquittamaug arrived with maize to sell to the starving colonists of Boston, Massachusetts.[5]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 354 Chaubunagungamaug, (2002)[1] 526 Hassanamisco Nipmuc (2004).[2] Possible total 1,400 (2008)[3] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Central Massachusetts ( | |

| Languages | |

| Nipmuc, Massachusett, currently English. | |

| Religion | |

| Traditionally Animism (Manito), Christianity. | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Narragansett, Pocomtuc, Pennacook, Massachusett, and other Algonquian tribes.[4] |

The colonists introduced pathogens, such as smallpox, to which the Native Americans had no prior exposure. They were also exposed to alcohol for the first time, which led to huge numbers of natives succumbing to the effects of alcoholism. With the passage of increasingly harsh laws against Indian culture and religion, the loss of land, legally and illegally, to growing English colonies, many of the Nipmuc joined Metacomet's rebellion in 1675, the results of which were disastrous. Many of the Nipmuc were interned on Deer Island in Boston Harbor and perished, and others were executed or sold into slavery in the West Indies.

The Reverend John Eliot arrived in Boston in 1631 and began an ambitious project to learn the Massachusett language, widely understood throughout New England, convert the Native Americans, and published a Bible and grammar of the language. His efforts, with colonial government backing, established several 'Indian plantations' or 'Praying towns'—predecessors to the Indian Reservation—where the Native Americans were coerced to settle and instructed in English customs, Christianity, but governed and preached to by other Native Americans and in their own dialects. By the 19th century, the Nipmuc were reduced to wards of the state that were administered by state-appointed commissioners. The passage of the Massachusetts Enfranchisement Act of 1869 effectively 'detribalised' the Nipmuc, and the last of the remaining Indian plantation lands were sold. Nipmuc communities continued to survive, and the tribe received state recognition in 1979, but efforts at federal recognition have not yet met with success.

Ethnonyms

The tribe is first mentioned in a 1631 letter by Deputy Governor Thomas Dudley as the Nipnet, 'people of the freshwater pond' due the inland location. This derives from Nippenet and includes variants such as Neipnett, Neepnet, Nepmet, Nibenet, Nopnat and Nipneet. In 1637, Roger Williams records the tribe as the Neepmuck, which derives from Nipamaug, 'people of the freshwater fishing place,' and also appears as Neetmock, Notmook, Nippimook, Nipmaug, Nipmoog, Neepemut, Nepmet, Nepmock, Neepmuk as well as modern Nipmuc(k). Colonists and the Native Americans themselves used this term extensively after the growth of the Praying towns.[6][7] The French referred to most New England Native Americans as Loup, 'the Wolf People,' but the name ȣmiskanȣakȣiak, the 'beaver tail-hill people,' was recorded as self-appellation of Nipmuc refugees that had fled to French Colonial Canada amongst the Abenaki.[8]

Language

Nipmucs probably spoke Loup A, a Southern New England Algonquian language.

Divisions or bands

Daniel Gookin, Superintendent to the Native Americans and assistant of Eliot, was careful to distinguish the Nipmuc (proper), Wabquasset, Quaboag and Nashaway tribes.[9] The situation was fluid since Native Americans unhappy with their chiefs were free to join other groups, and shifting alliances were made based on kinship, military, and tributary relationships with other tribes.[10][11] The formation of the Praying towns broke tribal divisions as the Native Americans were settled together, but four groups that are associated with the Nipmuc peoples survive today:

Chaubunagungamaug Nipmuck or Dudley Indians

- Descendants of the Praying town of Chaunbunagungamaug which is now located in the town of Webster on lands ceded by the town of Dudley, Massachusetts.

- The tribe uses several acres held in Webster, Massachusetts and across the border in Thompson, Connecticut.

Hassanamisco Nipmuc or Grafton Indians

- Descendants of the Praying town of Hassanamessit which is now located in Grafton, Massachusetts.

- The Cisco (Scisco, Ciscoe) family maintained their four acres from the final Hassamessit land sales and this is the current reservation.

Natick Massachusett or Natick Nipmuc

- The descendants of the Praying town of Natick, Massachusetts do not retain any of their original lands.

- The Natick are primarily descended from the Massachusett as well as Nipmuc ancestry, and qualify for state services as Nipmuc.[12]

Connecticut Nipmuc

- Descendants of various Nipmuc that survived or re-located to Connecticut.

- The Nipmuc of Connecticut, unlike in Massachusetts, are not recognized by their state.[13]

Legal status

State recognition

Governor Michael Dukakis issued Executive Order #126 which proclaimed that 'State agencies shall deal directly with ... [the] Nipmuc ... on matters affecting the Nipmuc Tribe' as well as calling for the creation of a state 'Commission on Indian Affairs.'[14] The subsequent establishment of the all-Indian Commission conferred state support for education, health care, cultural continuity, and protection of remaining lands for the descendants of the Wampanoag, Nipmuc and Massachusett tribes.[12][15] The state also calls for the examination of all human remains and to notify the Commission, who after the investigation of the State Archaeologist, decide the appropriate course of action.[16]

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts also cited the continuity of the Nipmuc(k) with the historic tribe and commended tribal efforts to preserve their culture and traditions. The state also symbolically repealed the General Court Act of 1675 that banned Native Americans from the City of Boston during King Philip's War.[17] The tribe also works closely with the state to undergo various archaeological excavations and preservation campaigns. The tribe, in conjunction with the National Congress of American Indians were against the construction of the sewage treatment plant on Deer Island in Boston Harbor where many graves were desecrated by its construction, and annually hold a remembrance service for members of the tribe lost over the winter during their internment during King Philip's War and protest against the destruction of Indian gravesites.[18]

Federal recognition efforts

On 22 April 1980, Zara Cisco Brough, landowner of Hassanamessit, submitted a letter of intention to petition for federal recognition as a Native American tribe which would confer certain rights, including state-to-state relations with the United States Congress and other support and services from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The Nipmuc, represented by just the Hassanamisco, were added to the Federal Register as Petitioner #69.[19] Members of the Chaubunagungamaug joined the efforts. On 20 July 1984, the BIA received the petition letter from the 'Nipmuc Tribal Council Federal Recognition Committee' co-signed by Zara Cisco Brough and her successor, Walter A. Vickers, of the Hassanamisco and Edwin 'Wise Owl' W. Morse, Sr. of the Chaubunagungamaug. On 2 February 1995, the Branch of Acknowledgement and Research (BAR) of the BIA to Edwin W. Morse, Sr. declared Petitioner #69 ready for active consideration, and requested the tribal membership lists in follow-up letter later that May. By 11 July 1995, the Nipmuc were placed on 'active consideration.'[20]

Pre-contact history

Palaeo-Indians entered the region from the south-west during the retreat of the Wisconsin Glacier sometime around 9000 BC. Evidence includes various chert tools that have been uncovered at the Bull Run site in Ipswich, Massachusetts as well as various riverside excavation sites in central portions of the state. These early peoples hunted the tundra environment, probably in search of caribou and other game.[21][22]

There was a great shift to more permanent hunting camps and expansion of tool making abilities. Fishing equipment, more advanced stone tools, burial culture, localised hunting, and development of stone bowls developed during the Archaic Period which began around 7000 BC. During this period, warmer weather would see forests develop and the extinction of the ice age megafauna. Settlements became more permanent and population densities increased.[23]

The Woodland Period began with the local development of agriculture sometime around 1000 BC and would last until contact occurred in the 17th century[24] Peoples during this period had adopted agriculture as well as slash-and-burn practices. This period would also see the adoption of ceramic pottery, introduction of the atlatl, and a culture that would have been recognisable to the later colonists. Populations increased and settlements became more permanent with the advent of agriculture. During the later stages of the period, pottery styles became influenced by Iroquois pottery styles and the bow and arrow were also adopted.[25]

Colonial-era history

17th century

Dutch and English sailors and adventurers began visiting New England, although the first permanent settlements in the region began after the settling of Plymouth Colony in 1620. These early seafarers introduced several diseases to which the Native Americans had no prior contact, resulting in epidemics with mortality rates as high as 90%. Smallpox wiped out many of the Native Americans from 1617–1619, 1633, 1648–1649 and 1666. Influenza, typhus, and measles also afflicted the Native Americans throughout the period. The colonists, such as the writings of Increase Mather, attributed the decimation of the Native Americans to God's providence in clearing the new lands for settlement.[26] The Nipmuc at the time of contact were a fairly large grouping, subject to their more powerful neighbours who provided protection, especially against the Pequot, Mohawk and Abenaki tribes that raided the area.[3] The colonists depended initially on the Native Americans for survival in the New World, and the Native Americans rapidly began to trade their foodstuffs, furs and wampum for the copper kettles, arms and metal tools of the colonists. Puritan settlers arrived in large numbers from 1620–1640, the 'Great Migration' which increased pressure to procure more land. Since the colonists had conflicting colonial and royal grants, the settlers quickly depended on Indian names on land deeds to mark legitimacy. This backfired, as John Wampas deeded off many lands to the colonists to curry favour, many of which were not even his.[27]

Indian plantations

The royal Charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony of 1692 called for the conversion of the Native Americans.[28] The English did not begin this in earnest until after the Pequot War proved their military superiority, with official backing in 1644.[29] Although many answered the call, the Rev. John Eliot who had learned the language from Massachusett tribe interpreters compiled an Indian Bible and a grammar of the language that was well understood from Cape Ann to Connecticut. The experiment also began for the settlement of the Native Americans on the 'Indian plantations' or 'Praying towns'. The Native Americans were instructed in English farming methods, culture, language but administered by Indian preachers and councillors often descended from the chiefly families. The Native Americans melded Indian culture and English ways, but were mistrusted by both the colonists and their non-converted brethren. The remnants of the plantations were sold off, and by the end of the 19th century, only the Cisco homestead in Grafton remained in possession of direct descendants of Nipmuc landholders. List of Indian Plantations (Praying towns) associated with the Nipmuc:[29][30][31]

Chaubunagungamaug, Chabanakongkomuk, Chaubunakongkomun, or Chaubunakongamaug

- 'The boundary fishing place,' 'fishing place at the boundary,' or 'at the boundary.'

- Webster, Massachusetts (on lands ceded from Dudley).

Hassanamesit, Hassannamessit, Hassanameset, or Hassanemasset

- 'Place where there is [much] gravel,' or 'at a place of small stones.'

- Grafton, Massachusetts.

Makunkokoag, Magunkahquog, Magunkook, Maggukaquog, or Mawonkkomuk

- 'Place of great trees,' 'granted place,' or 'place that is a gift.'

- Hopkinton, Massachusetts.

Manchaug, Manchauge, Mauchage, Mauchaug, or Mônuhchogok

- 'Place of departure,' 'place of marvelling,' 'island of rushes,' or 'island where reeds grow.'(?)

- Sutton, Massachusetts.

Manexit, Maanexit, Mayanexit

- 'Where the road lies,' 'where we gather,' 'near the path,' or 'place of meekness.'

- Thompson, Connecticut.

Nashoba

- 'The place between' or 'between waters.'

- Littleton, Massachusetts.

- Also settled by the Pennacook.

Natick

- 'Place of hills.'

- Natick, Massachusetts.

- Also settled by the Massachusett.

Okommakamesitt, Agoganquameset, Ockoocangansett, Ogkoonhquonkames, Ognonikongquamesit, or Okkomkonimset

- 'Plowed field place' or 'at the plantation.'

- Marlborough, Massachusetts.

Packachoag, Packachoog, Packachaug, Pakachog, or Packachooge

- 'At the turning place,' 'bends,' 'bare mountain place, or 'treeless mountain.'

- Auburn, Massachusetts.

Quabaug, Quaboag, Squaboag

- 'Red pond,' 'bloody pond' or 'pond before.'

- Brookfield, Massachusetts.

Quinnetusset, Quanatusset, Quantiske, Quantisset, or Quatiske, Quattissick

- 'Long brook' or 'little long river.'

- Thompson, Connecticut.

Wabaquasset, Wabaquassit, Wabaquassuck, Wabasquassuck, Wabquisset or Wahbuquoshish

- 'Mats for covering a lodge,' 'place of white stones,' or 'mats to cover the house.'

- Woodstock, Connecticut.

Wacuntuc, Wacantuck, Wacumtaug, Wacumtung, Waentg, or Wayunkeke

- 'A bend in the river.'

- Uxbridge, Massachusetts. originally Mendon, Massachusetts sold by Nipmuck as "Squnshepauk" Plantation

Washacum or Washakim

- 'Surface of the sea.'

- Sterling, Massachusetts.

- Also settled by the Pennacook.

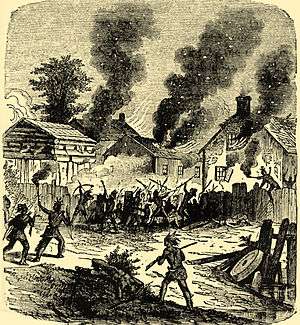

King Philip's War

The Massachusetts Bay Colony passed numerous legislation against Indian culture and religion. New laws were passed to limit the influence of the powwows, or 'shamans', and restricted the ability of non-converted Native Americans to enter English towns on Sabbath.[32] The Nipmuc were also informed that any unimproved lands were fair game for incorporation into the growing colony. These draconian measures and the increasing amount of land lost to the settlers led many Nipmuc to join the Wampanoag chief Metacomet in a rebellion against the English which would ravage New England from 1675–1676. The Native Americans that had already settled the Praying towns were interned on Deer Island in Boston Harbor over the winter where a great many perished from starvation and exposure to the elements. Although many of the Native Americans fled to join the uprising, other Native Americans joined the English. The Praying Indians were particularly at risk, as the war made all Native Americans suspect, but the Praying towns were also attacked by the 'wild' Native Americans that joined the rebellion.[33] The Nipmuc were major participants in the siege of Lancaster, Brookfield, Sudbury and Bloody Brook, all in Massachusetts,[34] and the tribe prepared thoroughly for conflict by forming alliances, and the group even had "an experienced gunsmith, a lame man, who kept their weapons in good working order."[35] The siege of Lancaster also lead to the capture of Mary Rowlandson, who was placed in captivity until ransomed for £20 and would later write a memoir of her captivity.[36] The Native Americans lost the war, and survivors were hunted down, murdered, sold into slavery in the West Indies or forced to leave the area.[37]

18th century

The Nipmuc regrouped around their former Praying towns and were able to maintain a certain amount of autonomy using the remaining lands to farm or sell timber. The population of the tribe was reduced as several outbreaks of smallpox returned in 1702, 1721, 1730, 1752, 1764, 1776 and 1792.[38] Land sales continued unabated, much of it used to pay for legal fees, personal expenses, and improvements to the reserve lands. By 1727, Hassanamisset was reduced to 500 acres from the original 7,500 acres with that land incorporated into the town of Grafton, Massachusetts, and in 1797, Chaubunagungamaug Reserve was reduced to 26 of their 200 acres.[39] The switch to the cattle industry also disrupted the native economy, as the colonists' cattle ate the unfenced lands of the Nipmuc and the courts did not always side with the Native Americans, but the Native Americans rapidly adopted the husbandry of swine since the changes in economy and loss of remaining pristine lands reduced ability to hunt and fish.[40] Since the Native Americans had few assets besides land, much of the land was sold to pay for medical, legal and personal expenses, increasing the number of landless Native Americans. With smaller numbers and landholdings, Indian autonomy was worn away by the time of the Revolutionary War, the remaining reserve lands were overseen by colony- and later state-appointed guardians that were to act on the Native Americans' behalf. However, the Hassanamisco guardian Stephen Maynard, appointed in 1776, embezzled the funds and was never prosecuted.[41]

Wars

New England rapidly became swept up in a series of wars between the French and English and their respective Indian allies. Many of the Native Americans of the New England had escaped to join the Abenaki and returned to fight against the English, however the local Native Americans were often conscripted as guides or scouts for the colonists. Wars occupied much of the century, including King William's War, (1689–1699), Queen Anne's War (1704–1713), Dummer's War (1722–1724), King George's War (1744–1748) and the French and Indian War (1754–1760). Many Native Americans also died in service of the Revolutionary War.[42][43]

Emigration

The upheaval of the Indian Wars and growing mistrust of the Native Americans by the colonists lead to a steady trickle, and sometimes whole villages, that fled to increasingly mixed-tribe bands either northward to the Pennacook and Abenaki who were under the protection of the French or westward to join the Mahican at increasingly mixed settlements of Schagticoke or Stockbridge, the latter of which eventually migrated as far west as Wisconsin.[44] This further dwindled Indian presence in New England, although not all the Native Americans dispersed. Those Nipmuc that fled eventually assimilated into either the predominate host tribe or the conglomerate that developed.[11]

Post-colonial history

19th century

The Native Americans were reduced to wards of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and continued to be represented by state-appointed guardians. Rapid acculturation and intermarriage led many to believe the Nipmuc had simply just vanished, due to a combination of romantic notions of who the Native Americans were and to justify the colonial expansion.[45] Native Americans continued to exist but fewer and fewer were able to live on the dwindling reserve lands and most left to seek employment as domestics or servants in White households, out to sea as whalers or seafarers, or into the growing cities where they became labourers or barbers.[46] Growing acculturation, intermarriage, and dwindling populations led to the extinction of the Natick Dialect of the Massachusett language, and only one speaker could be found in 1798.[47] One of the traditional things that survived was the peddling of native square-edged splint baskets and medicines.[48] The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, after investigating the condition of the Native Americans, decided to grant citizenship to the Native Americans with the passage of the Massachusetts Enfranchisement Act of 1869, which ultimately led to the sale of any of the remaining lands. Hassanamessit was divided up among a few families. In 1897, the last of the Dudley lands were sold, and the remaining Native Americans were housed in the 'poor house' on Lake Street in Webster, Massachusetts.[49]

Intermarriage

Intermarriage between Whites, Blacks or (Chikitis), and Native Americans began in early colonial times. Africans and Native Americans shared a complementary gender imbalance as few female slaves were imported into New England and many of the Indian men were lost to war or the whaling industry. Naturally, many unions between Native American women and African men occurred. Intermarriage with Whites was uncommon, due to colonial anti-miscegenation laws in place.[50] The children of such unions were accepted into the tribe as Native Americans, due to the matrilineal focus of Nipmuc culture, but to the eyes of their sceptical White neighbours, the increasingly Black phenotypes delegitimised their Indian identity.[51] By the 19th century, only a handful of pure-blood Native Americans remained, and Native Americans vanish from state and federal census records but are listed as 'Black', 'mulatto', 'colored' or 'miscellaneous' depending on their appearance.[50]

Censuses

In 1848, the Massachusetts Senate Joint Committee on Claims called for a report on the condition of several tribes that received aid from the Commonwealth. Three reports were listed: The 1848 'Denney Report' presented to the Senate the same year; the 1849 'Briggs Report', written by Commissioners F. W. Bird, Whiting Griswold and Cyrus Weekes and presented to Governor George N. Briggs; and the 1859 'Earle Report', written by Commissioner John Milton Earle that was submitted in 1861. Each report was more informative and thorough than the previous one. The Nipmuc require having an ancestor listed on these reports and the disbursement lists of funds from Nipmuc land sales. The lists did not count all Native Americans, as many Native Americans may have been well-integrated into other racial communities and due to the constant movement of Native Americans from place to place.

| Massachusetts 'Indian Censuses' | Dudley Indians | Dudley Surnames | Grafton Indians | Grafton Surnames |

| 1848, Denney Report | 51 | 2 | ||

| 1849, Briggs Report | 46 | Belden, Bowman, Daly, Freeman, Hall, Humphrey, Jaha, Kile (Kyle), Newton, Nichols, Pichens (Pegan), Robins, Shelby, Sprague and Willard. | 26 | Arnold, Cisco, Gimba (Gimby), Heeter (Hector) and Walker. |

| 1861, Earle Report | 77 | Bakeman, Beaumont, Belden, Cady, Corbin, Daley, Dorus, Esau, Fiske, Freeman, Henry, Hull, Humphrey, Jaha, Kyle, Nichols, Oliver, Pegan, Robinson, Shelley, Sprague, White, Willard and Williard. | 66 | Arnold, Brown, Cisco, Gigger, Hazard, Hector, Hemenway, Howard, Johnson, Murdock, Stebbins, Walker and Wheeler. |

- Some of the tribes' ancestors were recorded as 'colored' including individuals of the Brown, Cisco, Freeman, Gigger, Hemenway, Hull, Humphrey, Walker and Willard families.

- Some individuals of the Gigger family are labelled as 'miscellaneous Indians.'

- Some individuals were recorded as 'mixed' including individuals in the Bakeman, Belden, Brown, Kyle and Hector families.

- Some individuals of the Hall, Hector and Hemenway families have no label.

20th century

Attitudes towards Native American culture and history changed as antiquarians, anthropologists, institutions like the Boy Scouts as well as the 1907 appearance of Buffalo Bill Cody with many Native Americans in feathered headresses paying respects to Uncas, Sachem of the Mohegan. Despite the nearly four centuries of assimilation, acculturation, and the destruction of economic and community support from enfranchisement, certain Indian families were able to maintain a distinct Indian identity and cultural identity.[52] The turn of the century also saw active cultural and genealogical research by James L. Cisco and his daughter Sara Cisco Sullivan from the Grafton homestead, and worked closely with the remnants of other closely related tribes, such as Gladys Tantaquidgeon and the Fielding families of the Mohegan Tribe, Atwood L. Williams of the Pequot, and William L. Wilcox of the Narragansett. Together, various tribal members began sharing cultural memory, with pan-Indianism firmly taking root in the 1920s with Indian gatherings such as the Algonquin Indian Council of New England that met in Providence, Rhode Island and dances or pow-wows such as those at Hassanamessit in 1924. Plains Indian costume was often worn as potent statements of Indian identity and to prove their continued residence in the area and because much of the original culture had been lost.[53] Other Nipmuc individuals appeared at town pageants and fairs, including the 1938 appearance at the Sturbridge, Massachusetts bicentennial fair of many ancestors of today's Chaubunagungamaug Nipmuck.[54]

By the 1970s, the Nipmuc had made many strides. Many local members of the tribe were called upon to help with the development of the Native American exhibit at Old Sturbridge Village, a 19th-century living museum built in the heart of former Nipmuc territory.[55] State recognition was also achieved by the end of the same decade, re-establishing the Nipmuc people's relationship with the state and providing limited social services. The Nipmuc sought federal recognition in the 1980s. Tension between the Nipmuc Nation, which included the Hassanamisco and many descendants of the Chaubunagungamaug, based in Sutton, Massachusetts, and the rest of the Chaubunagungamaug, based in Webster, Massachusetts split the tribe in the mid-1990s. Divisions were caused by the frustrations with the slow pace of recognition as well as disagreements about gambling.[56][57]

190 acres of the Hassanamessit Woods in Grafton, believed to contain the remains of the praying village were under agreement for development for more than 100 homes. This property has significant cultural importance to the Nipmuc Tribal Nation because it is thought to contain the meetinghouse and the center of the old praying village.[58] However, The Trust for Public Land, the town of Grafton, the Grafton Land Trust, the Nipmuc Nation and the state of Massachusetts intervened. The Trust for Public Land purchased the property and kept it off the market until 2004, after sufficient funding was procured to permanently protect the property.[59] The property also has ecological significance as it is adjacent to 187 acres of Grafton owned land as well as 63 acres owned by the Grafton Land Trust. These properties will provide numerous recreational benefits to the public as well as play a role in protecting the water quality of local watersheds.[59]

In July 2013, the Hassanamisco band selected a chief, Cheryll Toney Holley to succeed Walter Vickers upon his resignation.

See also

References

- Martin, A. M. U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs. (2004). Final determination against federal acknowledgment of the nipmuc nation (fr25jn04-110). Retrieved from Federal Register Online via GPO Access website: http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/2004/04-14394.htm.

- The Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs. (2004). Martin issues final determination to decline federal acknowledgment of the nipmuc nation. Retrieved from website: http://www.doi.gov/archive/news/04_News_Releases/nipmuc.html Archived 2012-09-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Sultzman, L. (2008, October 29). Nipmuc history. Retrieved from http://www.dickshovel.com/nipmuc.html.

- Pritzker, B. M. (2000) A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples (p. 442). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Larnad, E. D. (1874). history of windham county, connecticut: 1600-1760. (Vol. I, p. 59). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Connole, D. A. (2007). Indians of the nipmuck country in southern new england 1630-1750, an historical geography. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. pp. 7 - 8.

- Hodge, R. W. (2006). Handbook of american indians, north of mexico. (Vol. II). Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Pub. p. 74.

- Day, G. M., Foster, M. K., & Cowan, W. (1998). In search of new england's native past: Selected essays. (p. 181). Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Connole, D. A. (2007). Indians of the nipmuck country in southern new england 1630-1750, an historical geography. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. pp. 8 - 10.

- Connole, D. A. (2007). pp. 8 - 10.

- Hodge, F. W. (1910). Nipmuc. Handbook of american indians north of mexico.. (Vol. III, p. 74). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

- Executive Office of Housing and Economic Development, Commission on Indian Affairs. (n.d.). Tuition waiver guidelines. Retrieved from Commonwealth of Massachusetts website: www.mass.gov/hed/docs/dhcd/ia/tuitionwaiver.doc.

- Blumenthal, R. Connecticut Department of Justice, Office of the Attorney General, Indian Affairs. (2002). Comments of the state of connecticut and the northeastern connecticut council of governments on the proposed findings on the petitions for tribal acknowledgement of the nipmuc nation and the webster/dudley band of the chaubunagungamaug nipmuck indians. Retrieved from http://www.ct.gov/ag/lib/ag/press_releases/2002/indian/nipmuc_brief.pdf.

- Mass. Executive Order #126. Dukakis 65th Governorship, 1976.

- Massachusetts General Laws, pt. I, Title II, Chapter 6A, § 8A.

- Massachusetts General Laws, pt. I, Title II, Chapter 7, § 38A.

- Massachusetts Session Laws. 181st General Court, 2005, Chapter 25.

- Nipmuc Nation. (1994). Remembering deer island: A cause worth of nipmuc support. Nipmucspohke, I(2), 2-3. Retrieved from nipmucspohke.homestead.com/Vol.I_Is.2.pdf

- Blumenthal, R. Connecticut Department of Justice, Office of the Attorney General, Indian Affairs. (2002).

- Martin, A. U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs. (2004). Summary under the criteria and evidence for final determination against federal acknowledgment of the webster/dudley band of chaubunagungamaug nipmuck indians (CBN-V02-D009). Washington, DC: Office of Federal Acknowledgment.

- Dincauze, D. F. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. (2007). The earliest americans: Northeast property types. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service Website.

- Robinson, B. S. (2011). Paleoindian mobility and aggregation patterns. Climate Change Institute, University of Maine, Orono, ME. Retrieved from http://climatechange.umaine.edu/Research/Contrib/html/11.html Archived 2013-11-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Mulholland, M. T., & Currin, K. (1997). Prehistory in new england. Biology Department, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA. Retrieved from http://www.bio.umass.edu/biology/conn.river/prehis.html Archived 2012-02-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Mulholland, M. T., & Currin, K. (1997).

- Murphree, D. S. (2012). Native america: A state-by-state historical encyclopedia. (pp. 731-732). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio.

- Kohn, G. C. (2010). Encyclopedia of plague and pestilence. (pp. 255-256). New York, NY: Infobase Publishing.

- Mandell, D. R. Behind the frontier: Indians in eighteenth-century eastern massachusetts. (p. 151). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- Charter of Massachusetts Bay (1629). Retrieved from http://undergod.procon.org/sourcefiles/MassachusettsCharter.pdf. p. 11.

- Shannon, T. J. (2005). Puritan conversion attempts. Retrieved from http://public.gettysburg.edu/~tshannon/hist106web/Indian Converts/the_puritans3.htm

- Nipmuc placenames of new england. (1995). [Historical Series I ed. #III]. (Nipmuc Indian Association of Connecticut ), Retrieved from http://www.nativetech.org/Nipmuc/placenames/mainmass.html

- Connole, D. A. (2007). Indians of the nipmuck country in southern new england 1630-1750, an historical geography. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. pp. 41, 90-120.

- Book of the General Lavves and Libertyes. Indians, §9 Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/coloniallawsofma00mass

- Drake, J. D. (1999). King philip's war: Civil war in new england, 1675-1676. (pp. 101-105). Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Mandell, D. R. (2010). King philip's war: Colonial expansion, native resistance, and the end of indian sovereignty. (pp. 60-75). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkinds University Press.

- Dennis A. Connole, The Indians of the Nipmuck Country in Southern New England, ... (2003), pg. 178 https://books.google.com/books?isbn=0786450118

- Waldrup, C. C. (1999). Colonial Women: 23 Europeans Who Helped Build a Nation. Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishers.

- Calloway, C. G. C. (1997). After king philip's war, presence and persistence in indian new england. (p. 2). Dartmouth, NH: Dartmouth College.

- Massachusetts Historical Society (1823). Collections of the massachusetts historical society. Chronological Table, X(II), 218. New York, NY: Johnson Reprint Corporation.

- Mandell, D. R. (2011). Tribe, race, history: Native americans in southern new england, 1780–1880. (pp. 20-21). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- O'Brien, J. M. (1997). Dispossession by Degrees: Indian Land and Identity in Natick, Massachusetts, 1650-1790. (pp. 6, 45). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Mandell, D. R. Behind the frontier: Native Americans in eighteenth-century eastern massachusetts. (p. 151). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- Calloway, C. G. C. (1997). After king philip's war, presence and persistence in indian new england. (p. 7). Dartmouth, NH: Dartmouth College.

- Mandell, D. (2011). King philip's war, colonial expansion, native resistance, and the end of indian sovereignty. (pp. 136-138). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Univ Pr.

- Calloway, C. G. C. (1997). After king philip's war, presence and persistence in indian new england. (pp. 40-45). Dartmouth, NH: Dartmouth College.

- Calloway, C. G. C. (1997). After king philip's war, presence and persistence in indian new england. (pp. 211-221). Dartmouth, NH: Dartmouth College.

- Mandell, D. R. 'The Saga of Sarah Muckamugg: indian and African Intermarriage in Colonial New England.' Sex, love, race: crossing boundaries in north american history. ed. Martha Elizabeth Hodes. (pp. 72-83). New York, NY: New York Univ Press.

- Goddard, I. & Bragdon, K. (1998). Native writings in massachusett. (p. 20). Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society.

- Prindle, T. (1994). 'Nipmuc Splint Basketry.' Retrieved from http://www.nativetech.org/weave/nipmucbask/.

- Holley, C. T. (2001). 'Nipmuc History.' Nipmuc Nation Website. Retrieved from http://nipmucnation.homestead.com/files/nipmuc_history.txt.

- Mandell, D. R. 'The Saga of Sarah Muckamugg: indian and African Intermarriage in Colonial New England.' Sex, love, race: crossing boundaries in north american history. ed. Martha Elizabeth Hodes. New York, NY: New York Univ Pr. pp. 72-83.

- Minardi, M(2010). Making slavery history, abolitionism and the politics of memory in massachusetts. New York, NY: Oxford Univ Pr US. pp 60-63.

- Mandell, D. R. (2011). Tribe, race, history: Native Americans in Southern New England, 1780–1880. (pp. 227-230). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Harkin, M. E. (2004). Reassessing revitalization movements: Perspectives from north america and the pacific islands. (p. 265-267). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- Artman, C. J. U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs. (2007). In re federal acknowledgment of Webster/Dudley band of Chaubunagungamaug Nipmuc Indians (IBIA 04-154-A). Retrieved from BIA Press website: "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-09. Retrieved 2014-01-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Murphree, D. S. (2012). Native america: A state-by-state historical encyclopedia. (p. 543). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio.

- Green, R. (28, September 28). Finding dims nipmuc casino prospects. Hartford Courant. Retrieved from http://articles.courant.com/2001-09-28/news/0109280356_1_federal-recognition-nipmuc-nation-tribe

- Adams, J. (2001, October 08). Nipmucs regroup, locals applaud as McCaleb denies recognition. Indian Country. Retrieved from http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/ictarchives/2001/10/08/nipmucs-regroup-locals-applaud-as-mccaleb-denies-recognition-86803.

- "Hassanamesitt Woods Protection Moves Forward (MA)". The Trust for Public Land.

- "Hassanamesitt Woods". The Trust for Public Land.

External links

- Commonwealth of Massachusetts Commission on Indian Affairs

- http://nipmucconnections.com/

- Chaubunagungamaug Nipmuck Indian Council

- Nipmuc Nation

- Hassanamisco Indian Museum

- Nipmuc Indian Association of Connecticut

- Nipmucspohke, Nipmuc Nation Newsletter

- Nipmuc History

- Project Mishoon

- Nipmuc Language - Home