Battle of Smolensk (1941)

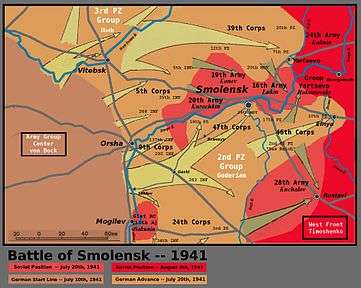

The First Battle of Smolensk (German: Kesselschlacht bei Smolensk "Cauldron-battle at Smolensk"; Russian: Смоленская стратегическая оборонительная операция, Smolenskaya strategicheskaya oboronitelnaya operatsiya, "Smolensk strategic defensive operation") was a battle during the second phase of Operation Barbarossa, the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union, in World War II. It was fought around the city of Smolensk between 10 July and 10 September 1941, about 400 km (250 mi) west of Moscow. The Ostheer had advanced 500 km (310 mi) into the USSR in the 18 days after the invasion on 22 June 1941.

The Soviet 16th, 19th and the 20th armies were encircled and destroyed just to the south of Smolensk, though many of the men from the 19th and 20th armies managed to escape the pocket. Some historians have asserted that the cost to the Germans during this drawn-out battle and the delay in the drive towards Moscow led to the victory of the Red Army in the Battle of Moscow of December 1941.

Background and planning

On 22 June 1941, the Axis nations invaded the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa. At first, the campaign met with spectacular success, as the surprised Soviet troops were not able to offer coordinated resistance. After three weeks of fighting, the Germans had reached the Dvina and Dnieper rivers and planned for a resumption of the offensive. The main attack aimed at Moscow, was carried out by Army Group Centre (Fedor von Bock). Its next target on the way to the Soviet capital was the city of Smolensk. The German plan called for the 2nd Panzer Group (later 2nd Panzer Army) to cross the Dnieper, closing on Smolensk from the south, while the 3rd Panzer Group (later 3rd Panzer Army) was to encircle the town from the north.[13]

After their initial defeats, the Red Army began to recover and took measures to ensure a more determined resistance and new defensive line was established around Smolensk. Stalin placed Field Marshal Semyon Timoshenko in command and transferred five armies out of the strategic reserve to Timoshenko. These armies had to conduct counter-offensives to blunt the German drive. The German high command (OKW) was not aware of the Soviet build-up until they encountered them on the battlefield.[13][14]

Facing the Germans along the Dnieper and Dvina rivers were stretches of the Stalin Line fortifications. The defenders were the 13th Army of the Western Front and the 20th Army, 21st Army and the 22nd Army of the Soviet Supreme Command (Stavka) Reserve. The 19th Army, was forming up at Vitebsk, while the 16th Army was arriving at Smolensk.[15][14]

In Soviet histories, the battles around Smolensk are divided into phases and operations to halt the German offensive and the pincers

- Battle of Smolensk (10 July – 10 September 1941)

- Smolensk Defensive Operation (10 July – 10 August 1941)

- Smolensk Offensive Operation (21 July – 7 August 1941)

- Rogechev-Zhlobin Offensive Operation (13–24 July 1941)

- Gomel-Trubchevsk Defensive Operation (24 July – 30 August 1941)

- Dukhovschina Offensive Operation (17 August – 8 September 1941)

- Yelnia Offensive Operation (30 August – 8 September 1941)

- Roslavl-Novozybkov Offensive Operation (30 August – 12 September 1941)

The Operation

Prior to the German attack, the Soviets launched a counter-offensive; on 6 July, the 7th and 5th Mechanized Corps of the Soviet 20th Army attacked with about 1,500 tanks near Lepiel. The result was a disaster, as the offensive ran directly into the anti-tank defenses of the German 7th Panzer Division and the two Soviet mechanized corps were virtually wiped out.[16]

On 10 July, Guderian's 2nd Panzer Group began a surprise attack over the Dnieper, his forces overran the weak 13th Army and by 13 July, Guderian had passed Mogilev, trapping several Soviet divisions. His spearhead unit, the 29th Motorised Division, was already within 18 km (11 mi) of Smolensk. The 3rd Panzer Group had attacked, with the 20th Panzer Division establishing a bridgehead on the eastern bank of the Dvina river, threatening Vitebsk. As both German panzer groups drove east, the 16th, 19th and 20th armies faced the prospect of encirclement around Smolensk. From 11 July, the Soviets tried a series of concerted counter-attacks. The Soviet 19th Army and 20th Army struck at Vitebsk, while the 21st and the remnants of the 3rd Army attacked against the southern flank of 2nd Panzer Group near Bobruisk.[15]

Several other Soviet armies also attempted to counter-attack in the sectors of the German Army Group North and Army Group South. This effort was apparently part of an attempt to implement the Soviet prewar general defense plan. The Soviet attacks managed to slow the Germans but the results were so marginal that the Germans barely noticed them as a large coordinated defensive effort and the German offensive continued.[17]

Hoth's 3rd Panzer Group drove north and then east, parallel to Guderian's forces, taking Polotsk and Vitebsk. The 7th Panzer Division and 20th Panzer Division reached the area east of Smolensk at Yartsevo on July 15. At the same time, the 29th Motorized Division, supported by the 17th Panzer Division broke into Smolensk, captured the city except for the suburbs and began a week of house-to-house fighting against counter-attacks by the 16th Army. Guderian expected that the offensive would continue towards Moscow as its main focus and sent the 10th Panzer Division to the Desna River to establish a bridgehead on the east bank at Yelnya and cleared that as well by the 20th. This advanced bridgehead became the center of the Yelnya Offensive, one of the first big coordinated Soviet counter-offensives of the war.[18]

This objective was 50 km (31 mi) south of the Dnepr and well clear of the objective of liquidating the armies trapped at Smolensk. Under Fuhrer Directive 33 issued on July 14, the main effort of the Wehrmacht was re-orientated away from Moscow towards a deep encirclement of Kiev in Ukraine and Bock was becoming impatient, wanting Guderian to strike north and link up with Hoth's Panzer Group so resistance in the city could be mopped up.[18][19]

On July 27, Bock held a conference at Novy Borisov, which was also attended by Commander-in-Chief Walther von Brauchitsch, the head of the Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH), the Supreme High Command of the Wehrmacht. The generals were required to sit without an opportunity to comment, while a memorandum was read to them by one of Brauchitsch's aides, instructing them that they were to strictly follow Fuhrer Directive 33 and were under no circumstance to try to push further east. They were ordered to concentrate on mopping up, refurbishing equipment, restocking supplies and straightening the German front line, which had become more of an "S" shape, due to the advances of Guderian and Hoth. Coming away from this meeting, Hoth and Guderian were angry and frustrated. Guderian wrote in his journal that night that Hitler "preferred a plan by which small enemy forces were to be encircled and destroyed piecemeal and the enemy thus bled to death. All the officers who took part in the conference were of the opinion that this was incorrect". Whether or not this was true, it was this meeting that some have pointed to that marked a critical point where the Wehrmacht leadership broke trust with Hitler. After returning to his post, Guderian conspired with Hoth and Bock to "delay the implementation" of Directive 33, in defiance of the orders of the Fuhrer and OKH. Guderian hastily put together a plan of attack for his and Hoth's forces for August 1, the Roslavl-Novozybkov Offensive Operation.[20]

In the north, the 3rd Panzer Group was moving much more slowly. The terrain was swampy, made worse by rain and the Soviets were fought to escape the trap. On 18 July, the armored pincers of the two panzer groups came within 16 km (9.9 mi) of closing the gap. Timoshenko put newly promoted Konstantin Rokossovsky, who had just arrived from the Ukrainian front, in charge of assembling a stopgap force, which held the attack of the 7th Panzer Division and with continuous reinforcements, temporarily stabilized the situation. The open gap allowed Soviet units to escape that were then pressed into service, holding the gap open.[18][21]

The Soviets transferred additional troops from newly formed armies into the region around Smolensk, namely the 29th, 30th, 28th, and 24th Armies. These newly built formations would, immediately upon arrival, start a heavy counter-attack against the German forces around the Smolensk area from 21 July on. This put a heavy strain on the overextended Panzer forces, which had to cover a large area around the perimeter. However, poor coordination and logistics on the part of the Soviets allowed the Germans to successfully defend against these offensive efforts, while continuing to close the encirclement. The Soviet attacks would last until 30 July, when the Germans finally repelled the last of them.[18][19]

Finally, on 27 July, the Germans were able to link up and close the pocket east of Smolensk, trapping large portions of 16th, 19th, and 20th Armies. Under the leadership of 20th Army, Soviet troops managed to break out of the pocket in a determined effort a few days later, assisted by the Soviet offensive efforts along the Smolensk front line. In the end, about 300,000 men were taken prisoner when the encirclement was re-established and the pocket eliminated.[9][10][22]

Aftermath

The Battle of Smolensk was another severe defeat for the Red Army in the opening phase of Operation Barbarossa. For the first time, the Soviets tried to implement a coordinated counter-attack against a large part of the front; although this counter-attack turned into a military disaster, the stiffening resistance showed that the Soviets were not yet defeated and that the Blitzkrieg towards Moscow was not going to be an easy undertaking. Dissent within the German high command and political leadership was exacerbated. The leaders of the General Staff, Franz Halder and Brauchitsch and commanders like Bock, Hoth and Guderian counselled against dispersing the German armoured units and to concentrate on Moscow. Hitler reiterated the lack of importance of Moscow and of strategic encirclements and ordered a concentration on economic targets such as Ukraine, the Donets Basin and the Caucasus, with more tactical encirclements to weaken the Soviets further. The German offensive effort became more fragmented, leading to the Battle of Kiev and the Battle of Uman. The battles were German victories but costly in time, men and equipment on their approach towards Moscow, allowing the Soviets time to prepare the defenses of the city.[23][24][25][26][19][27]

Notes

- a Russel Stolfi wrote "Panzer Groups 2 and 3 destroyed or captured 3,273 Soviet tanks.[4]

- b David Glantz wrote that "although the two [7th and 5th Soviet] mechanized corps fielded a total of over 1,500 tanks on paper, it is likely as many as two-thirds of their tanks broke down due to mechanical problems even before they reached the battlefield".[6]

References

- R. Kirchubel (2016). Atlas of the Eastern Front. Osprey publishing. ISBN 978-1-47280774-8.

- Glantz 2010, pp. 88."By Soviet definition, the battle for Smolensk began on 10 July, when Hoth's Third and Guderian's Second Panzer Groups, supported by the Second Air Fleet, commenced their twin thrusts across the Dnepr River."

- Glantz 2010, p. 43.

- Stolfi 1993, p. 164.

- Krivosheev 1997, p. 116.

- Glantz 2010, pp. 72–73.

- Statyuk 2006, pp. 38-39

- "WW2Stats com". Archived from the original on 31 May 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- Glantz 2010, p. 576.

- Klink 1998, p. 536.

- Glantz 1995, p. 293.

- Krivosheev 1997, p. 260.

- Glantz 1995, p. 58.

- Ziemke 1987, pp. 29–30.

- Glantz 1995, pp. 58–59.

- Glantz 2010, pp. 70–79, 86.

- Glantz 1995, p. 59.

- Glantz 1995, pp. 60–61.

- Ziemke 1987, pp. 32–33.

- Clark 1965, pp. 91–94.

- Clark 1965, p. 90.

- Ziemke 1987, pp. 29–32.

- Evans 2008, pp. 198–199

- Glantz 1995, p. 62.

- Glantz 2010, pp. 576–578.

- Klink 1998, pp. 535–536.

- Clark 1965, p. 96.

Bibliography

- Clark, Alan (1965). Barbarossa: The Russian-German Conflict, 1941–45. New York: Morrow. ISBN 0-688-04268-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, Richard J. (2008). "2". The Third Reich At War. London & New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-101548-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glantz, David M. (2010). Barbarossa Derailed: The Battle for Smolensk 10 July – 10 September 1941. Solihull, England: Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-906033-72-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glantz, David M. (1995). When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0899-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Klink, Ernst (1998). "The Conduct of Operations: The Army and Navy". In Boog, Horst; Förster, Jürgen; Hoffmann, Joachim; Klink, Ernst; Müller, Rolf-Dieter; Ueberschär, Gerd R. (eds.). The Attack on the Soviet Union. Germany and the Second World War. IV. Translated by McMurry, Dean S.; Osers, Ewald; Willmot, Louise. Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt (Military History Research Office (Germany)). Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 941–1020. ISBN 0-19-822886-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Krivosheev, Grigori F. (1997). Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-280-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Statyuk, Ivan (2006). Смоленское сражение 1941 [The Battle of Smolensk, 1941] (in Russian). Moscow: Tseykhgauz. ISBN 5-9771-0017-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stolfi, R. H. S. (1993). Hitler's Panzers East: World War II Reinterpreted. Oklahoma City: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2581-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ziemke, Earl F. (1987). Moscow to Stalingrad. Center of Military History, United States Army. ISBN 9780880292948.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)