Battle of Samarinda

The Battle of Samarinda (29 January–8 March 1942) was a mopping up operation in the series of the Japanese offensive to capture the Dutch East Indies. After capturing the oil refineries at Balikpapan, Japanese forces advanced north to capture the strategic oil drilling site in and around Samarinda and the oil pipelines that linked both cities.

Background

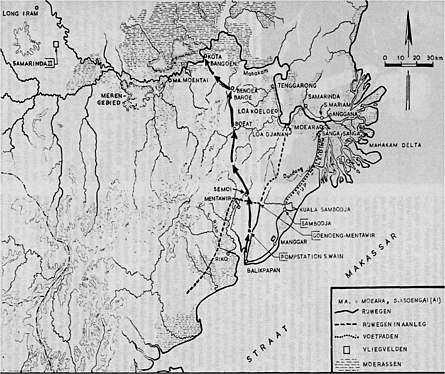

Before the war, Samarinda held a strategic significance due to the oilfields of the Bataafse Petroleum Maatschappij (BPM; Batavian Petroleum Company) that was located north and south of the Mahakam River. The drilling site in Sanga Sanga (named "Louise"), in particular, supplied a large amount of oil for the refineries in Balikpapan. Oil from Sanga Sanga went through a 70 km pipeline via Sambodja (Samboja) to Balikpapan. Furthermore, the Dutch also established a coal mine in the Loakoeloe (Loa Kulu) area, run by the Oost Borneo Maatschappij (OBM; East Borneo Company).[3]

The Japanese had also recognized Samarinda's importance as a center of oil and coal production, in addition to its substantial port and replenishing facilities. In 1939, the Sanga Sanga Oilfields produced around 1 million tons of oil annually, about 20% of the annual quantity that Japan needed.[4] And with that, Samarinda became one of Japan's major seizure target in its plan to annex the Dutch East Indies.[5]

Order of Battle

Japan

Ground Forces

Kume Detachment (Commander: Lt. Col. Motozō Kume):[6]

- 1st Battalion, 146th Infantry Regiment (minus 2nd and 4th Company)

- One engineer platoon

- One radio squad

Netherlands

Ground Forces

Samarinda Detachment (Commander: Capt. G.A.C. Monteiro):[7][8]

- Command Staff (Commander: Lt. J.P. Scheltens)

- One company of 23x 4-man Carabine Machine Gun Groups armed with Madsen machine guns

- Mobiele Eenheid/Mobile Unit (Commander: Sgt. Maj. A.E. Hillebrandt):

- ca. 25 troops

- Two overvalwagens

- One motorcycle

- 2x Machine Gun Sections (Commander: Sgt. Maj. H.A. Gorter):

- 3x 6,5 mm Vickers Machine Gun per Section

- 2x Mortar Sections (Commander: Sgt. Tomasoa):

- 3x 80 mm mortar per Section

- 3x 75 mm (non-mobile) artillery at Mariam River (Commander: Asst. Officer B. van Brussel)

- Six-man demolition engineer detachment, supported by 60 conscripted BPM employees

- 40 militia and Landwacht conscripts, 15 of whom were OBM employees and are assigned for demolition tasks there.

- Six-man hospital staff, and ca. 35-man Red Cross staffs

Dutch Plans

In December 1941, the General Headquarters in Bandung assigned the Samarinda Detachment the following tasks:[9]

- Prevent enemy landing at Sanga Sanga and Anggana

- Prevent the drilling sites at Sanga Sanga and Anggana from falling undamaged into enemy hands

- In the face of a numerically superior enemy, conduct guerrilla warfare that focused on harassing the enemy's repair work on the drilling sites

Since the Sanga Sanga drilling sites can be easily accessed from the sea through the large number of arms of the Mahakam delta, the Dutch have placed several defensive measures and detectors in the approaches to Mahakam River. To signal suspicious ship movements, Monteiro set up telephone posts at various delta mouths that will inform him of any ship movements. A Dutch battery of 3x 75 mm guns had also been installed near Mariam River to prevent enemy ship from approaching the mouth of the Sanga Sanga River.[10]

At the junction of Sanga Sanga River and Mahakam (Sanga Sanga Moeara), the Dutch also set up concrete casemates as part of a defensive position to delay an enemy landing near the mouth of the river. In addition, Monteiro also placed a strong guard at Dondang stream bridge in Tiram River, near where the oil pipeline was laid. To help prevent the drilling sites to be captured intact, the Dutch have prepared the destruction plan since early January 1942 and have evacuated the families of BPM staff at Sanga Sanga and Anggana to Samarinda.[11][12]

Japanese Plans

Even though its oilfields held a special significance, the Japanese plan for the capture in Samarinda solely consisted of a mopping up operation. At first, the plan was for Japanese troops enter the city via landing boats through the Mahakam Delta. However, in late January, the plan was changed to having Sanga Sanga and Samarinda be seized by land.[13]

For this operation, the Kume Detachment will advance from Balikpapan via Mentawir to Loa Djanan (Loa Janan) up north, while the main force will advance along the Balikpapan — Sambodja (Samboja) — Samarinda road and conducted mopping up operation in Samarinda's vicinity.[14]

The Battle

Sanga Sanga Oilfield Demolition

On 18 January, Col. C. van den Hoogenband, commander of Dutch forces in Balikpapan telephoned Monteiro, informing him that the demolition of oilfields in Balikpapan will commence, after Dutch planes spotted the Japanese invasion fleet near Cape Mangkalihat. Based on the phone call, Monteiro also decided to begin the demolition process of the Sanga Sanga oilfield. Under the command of Lt. Naber, and aided by conscripted BPM employees, the demolition began at 09:00 on 20 January. The well-organized and properly executed plan means that by 18:00, Sanga Sanga oilfield had been thoroughly and systematically destroyed. The demolition teams then left for Samarinda II Airfield, before being evacuated to Java.[15][16]

Dutch Defense Realigment

On 22 January, the General Headquarters (AHK) in Bandung instructed Monteiro to leave 4 brigades (ca. 15-18 man each) in Sanga Sanga to prevent enemy landing along the Mahakam River. Monteiro perceived that since his forces does not have the adequate manpower for this order, he advised for his force to focus on the defense of the road that ran from the Mahakam River all the way to Samarinda II (2,5 km long). AHK ignored his advice, and the original order had to be carried out. But then, AHK clarified their position again, and instructed Monteiro to conduct the delaying action on the river, in boats. At the time, Monteiro only had two available vessels for this task: Triton (A Gouvernementsmarine vessel) and the P-1 patrol boat that escaped from Tarakan and arrived on 19 January[17].

Monteiro ordered Sgt. Maj. J. Schrander to stay behind with 80 men and several remaining demolition engineers at Sanga Sanga. After conducting the final destruction to the oilfields, Schrander's detachment must inflict as much casualty on the Japanese as possible. In the meantime, Monteiro requisitioned all available sailing vessels - ca. forty ships, ranging from small motor boats to 100 tonnes coasters - and divided them into four groups, staffed by about 250 people under a commander. Monteiro also moved his headquarter from Sanga Sanga to Samarinda and had Lt. Hoogendorn destroyed the oil pipeline along the Dondang stream. Finally, any troops that are not suitable for the river delaying action are withdrawn to Samarinda II.[18]

On 24 January, Hoogenband evacuated his troops from Balikpapan, rendering Monteiro to rely on civilian reports for intelligence sources. Even though reports gave unclear picture of the situation at Balikpapan, it pointed out that Japanese forces intended to advance through the pipeline to Sanga Sanga and also over the water, with expectations that they will arrive in Samarinda by February.[19]

Advance of Kume Detachment

On 29 January, Monteiro was informed that the Kume Detachment began to cross the Doendang River. He immediately instructed Schrander to conduct the final demolitions of Sanga Sanga, and take offensive actions against the enemy. Shortly after giving the order, connection with Sanga Sanga was broken. As the skirmish between Schrander's and Kume's forces began, the former quickly lost control of his four brigades, as the brigade commanders had already lost their footing. Before long, Schrander's troops was shattered and retreated in disarray westwards to Loa Djanan. Monteiro soon realized that the Kume Detachment will advance along a partially constructed road that runs from Balikpapan to Loa Djanan. On 31 January, Samarinda was razed and Monteiro moved his headquarters to Loa Djanan.[20][21]

On 1 February, what's left of Schrander's detachment reached Loa Djanan and informed Monteiro that the Kume Detachment had beaten them back. They also informed that on January 30, Kume's forces had crossed the Tiram River from the south. Monteiro sent a patrol to Sanga Sanga to find Schrander, to no avail. Civilian reports also indicated that there was heavy fighting in Sanga Sanga. Because of this Monteiro realized that it would be useless to maintain the Dutch battery at Marian River. He ordered van Brussel, commander of the battery, to destroy the guns and fall back to Loa Djanan.[22]

On 2 February, Dutch sentries placed 12 km from Loa Djanan engaged a Japanese column that had been moving from Balikpapan to Mentawir. Underpowered, the sentries were beaten back to Loa Djanan by the evening, after which Monteiro moved his headquarters northward to Tenggarong in order to continue delaying the Japanese advance along the Mahakam River to Samarinda II. At Loa Koeloe (Loa Kulu), Dutch forces destroyed the OBM coal mine, before receiving intelligence that Kume's forces have occupied Loa Djanan. Taking no respite, Kume moved his troops east and captured Samarinda on 3 February. Along his advance, the Japanese have also attempted to entered Mahakam river via sea but failed, with two destroyers running aground in one of the delta arms.[23]

Monteiro's Delaying Actions

To conduct the delaying action on the river, the Dutch equipped Triton with a light gun, a pair of high-level machine guns and added improvised armor plates to the hull. The ship left Tenggarong on 3 February at 04:00 hours to recon in force the area around Loa Djanan. Five hours later, the ship returned with the information that Japanese forces had occupied the town. The ship, raked with machine gun fire, had caused substantial casualties on the Japanese force for the cost of two injured crews.[24]

From his view, since the Japanese has not shown any intention to advance further inland after occupying Samarinda, Monteiro planned to use his remaining available troops to raid Samarinda. Once again, AHK rejected the plan since he does not even have enough troops to delayed a still-possible enemy advance, which occurred on 8 February, as Japanese forces began marching towards Tenggarong. Before the town was occupied by the afternoon on the same day, Monteiro had already moved his headquarters again 15 minutes further upstream.[25]

Triton, now under the command of Lt. Scheltens, moved into Tenggarong on 10 February and promptly came under heavy fire. During the skirmish, many of its civilian crew jumped overboard, and the ship to began to drift off. Scheltens took the helm and regain the steering control. Throughout a 20-minute firefight, he managed to prevent outright panic and lead the counterfire. Nevertheless, the engagement created an atmosphere of shell-shock among the remaining civilian crew. As they began to desert the fight, morale among the Dutch forces began to be strained, as the local troops followed in their footsteps and went back to their families in Samarinda. To kept the delaying action going, AHK sent naval personnel replacements from Java.[26]

By 15 February, the remainder of Samarinda detachment based themselves in Kota Bangoen (Kota Bangun) and sent 4 brigades under Scheltens southward to Benua Baroe (Benua Baru) to close the route from Tenggarong to the town. At that point, Monteiro only had three weakly armed combat vessels to delay any attack from the river. In addition to the Triton, there was also the Mahakam, a former Binnenlands Bestuur (BB; Interior Administration) ship. Dutch troops armed Mahakam with a 20-mm gun and several machine guns. P-1's defective features, however, had rendered it out of service. Monteiro also evacuated the soldiers families westwards to prevent further desertion.[27]

Trying to regain the initiative, he sent spies to Samarinda and Tenggarong to gather intelligence on possible attacks[28]; Scheltens even disguised himself as an Arab Haji and gathered information from visiting many kampungs (villages). Meanwhile, the commander of Samarinda II, Maj. Gerard du Rij van Beest Holle was appointed as the acting commander of all Dutch military forces in Borneo. Monteiro immediately urged him to relay the delaying action's futility and the need to attack Samarinda to AHK, due to several factors:[29]

- From Kota Bangoen to Moeara Moentai and further on, the Mahakam River can only be navigated by small war vessels

- Monteiro only had three boats to continue the order

- An attack on Samarinda would do more harm to the Japanese and ensure the destruction of any remaining vital facilities

Still, van Beest Holle remained adamant about continuing the fight along the river to ensure Samarinda II's safety. On 1 March, however, AHK consented to Monteiro's plan, if he agreed to continue to river action in case of failure. Yet the few troops at his disposal means that Monteiro could not meet this term; he pointed out that he need at least two more companies, to no avail. On 5 March, the spies sent reports of an imminent attack on Kota Bangoen via land and river.[30][31]

The next day, a patrol from Benua Baroe came in contact with Japanese patrols and retreated back to the town, as Japanese troops began to make camp just one hour away. At dawn on 7 March, Tenggarong came under a fierce attack. The fighting continued for three hours until 10:00, when the weight of Japanese machine guns and mortars forced the brigade to retreat in panic and disorder to Kota Bangoen. Out of 80 troops at Benua Baroe, 10 of them, along with their commander Lt. Van Mossel did not reached Kota Bangoen at 02:00 the next day. Monteiro instructed the Triton, an OBM tug and a speedboat to wait for him until 06:00, before falling back upstream.[32][33]

As the troops from Benua Baroe reached Kota Bangoen, they immediately boarded river vessels along with the rest of Monteiro's troops and left for Moeara Moentai (Muara Muntai) under cover of the aforementioned ships. The convoy docked and set up their command post in the town by 05:00 under the distant sound of gunfire. Two hours later, several Dutch soldiers arrived in a battered speedboat and informed Monteiro that the combat vessels at Kota Bangoen had engaged with Japanese armored sloops. With Triton badly shot up and the OBM tug could no longer be used from the fight, Mahakam, along with disorganized KNIL troops in wooden boats are all that remained of the river force.[34]

Monteiro decided to organized the last resistance in Samarinda II and went there immediately to inform van Beest Holle of his disposition. While en route, however, he received a telegram about the ongoing negotiation between Dutch and Japanese commanders on Java at 09:00. At noon, the radio announced the unconditional surrender of all Dutch forces in the Netherlands East Indies, forcing him to lay down his arms and ended the last resistance in East Borneo.[35]

Aftermath

Lt. Van Hossel evaded capture until 11 March, when Japanese troops caught up with him at Moeara Moentai. By 19 March, Japanese forces had rounded up all Dutch troops and detained them in Samarinda. Maj. van Beest Holle died in captivity in Tarakan on 4 June, 1944.

On the 30th of July 1945 around 144 to about 148 inmates (sources vary) were rounded up and driven to the mine at Loa Kulu. There the inmates were told they were sentenced to death after which the women were separated from the men and children. First the Japanese soldiers mutilated the women to death, after which they threw all the children down the mine shaft, then finally the men who first had to witness what happened to their wives and children were decapitated by Japanese soldiers. Their bodies and severed heads were thrown down the mine shaft as well, just as the mutilated bodies of the women.[36]

After the war, Capt. Monteiro was awarded the Bronze Lion and Lt. Scheltens received the Bronze Cross.[37]

Liberation

Samarinda remained under Japanese occupation until September 1945, when it was liberated by the 2/25th Battalion of the Australian 7th Division. The Australians also discovered the human remains in the mine shaft at Loa Kulu. A monument has been erected to commemorate the victims of what is now known as the Loa Kulu Massacre. [38]

Notes

- Nortier (1981), pp. 319

- Nortier (1981), pp. 327

- Nortier (1981), pp. 318

- Remmelink (2015), pp. 12

- Remmelink (2018), pp. 21

- Nortier (1981), pp. 326

- Nortier (1981), pp. 319-320

- Koninklijke Nederlands Indische Leger (1948), pp. 637

- Koninklijke Nederlands Indische Leger (1948), pp. 637

- Nortier (1981), pp. 638

- Koninklijke Nederlands Indische Leger (1948), pp. 638

- Nortier (1981), pp. 321

- Remmelink (2015), pp. 221

- Nortier (1981), pp. 326

- Koninklijke Nederlands Indische Leger (1948), pp. 639

- Nortier (1981), pp. 323

- Nortier (1981), pp. 324

- Nortier (1981), pp. 324

- Nortier (1981), pp. 325

- Koninklijke Nederlands Indische Leger (1948), pp. 639

- Nortier (1981), pp. 326

- Koninklijke Nederlands Indische Leger (1948), pp. 639

- Koninklijke Nederlands Indische Leger (1948), pp. 639

- Nortier (1981), pp. 327

- Koninklijke Nederlands Indische Leger (1948), pp. 641

- Nortier (1981), pp. 328

- Nortier (1981), pp. 329

- Koninklijke Nederlands Indische Leger (1948), pp. 641

- Nortier (1981), pp. 329

- Koninklijke Nederlands Indische Leger (1948), pp. 641

- Nortier (1981), pp. 329

- Koninklijke Nederlands Indische Leger (1948), pp. 641

- Nortier (1980), pp. 330

- Nortier (1981), pp. 330

- Koninklijke Nederlands Indische Leger (1948), pp. 641

- De moorden van 30 juli 1945 Loa Kulua, West Borneo https://indisch4ever.nu/2019/01/20/de-moorden-van-30-juli-1945-loa-kulua-west-borneo/

- Nortier (1981), pp. 331

- Koloniale Monumenten https://kolonialemonumenten.nl/2019/01/27/loa-kulu-samarinda-1946/

References

- Koninklijke Nederlands Indisch Leger (1948). De Strijd in Oost-Borneo in de Maanden Januari, Februari en Maart 1942 (2). Militaire Spectator, 117-11. Retrieved from https://www.militairespectator.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/uitgaven/1918/1948/1948-0635-01-0184.PDF

- Nortier, J.J (1981). Samarinda 1942, de riviervloot van een landmachtkapitein. Militaire Spectator, 150-7. Retrieved from https://www.kvbk.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/uitgaven/1981/1981-0318-01-0085.PDF

- Remmelink, W. (Trans.). (2015). The invasion of the Dutch East Indies. Leiden: Leiden University Press. ISBN 978 90 8728 237 0

- Remmelink, W. (Trans.). (2018). The Operations of the Navy in the Dutch East Indies and the Bay of Bengal. Leiden: Leiden University Press. ISBN 978 90 8728 280 6