Battle of Preston (1648)

The Battle of Preston (17–19 August 1648), fought largely at Walton-le-Dale near Preston in Lancashire, resulted in a victory for the New Model Army under the command of Oliver Cromwell over the Royalists and Scots commanded by the Duke of Hamilton. The Parliamentarian victory presaged the end of the Second English Civil War.

| Battle of Preston | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second English Civil War | |||||||

Battle of Preston 1648 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 11,000 (not all were engaged in the battle.)[1] | 8,600-9,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2,000 killed 9,000 captured[2] | under 100 killed[3] | ||||||

Campaign

On 8 July 1648, when the Scottish Engager army crossed the Border in support of the English Royalist,[4] the military situation was well defined. For the Parliamentarians, Cromwell besieged Pembroke in South Wales, Fairfax besieged Colchester in Essex, and Colonel Edward Rossiter besieged Pontefract and Scarborough in the north. On 11 July, Pembroke fell and Colchester followed on 28 August.[5] Elsewhere, however, the rebellion, which had been put down by rapidity of action rather than sheer weight of numbers, still smouldered. Charles, the Prince of Wales, with the fleet cruised along the Essex coast. Cromwell and John Lambert, however, understood each other perfectly, while the Scottish commanders quarrelled with each other and with Sir Marmaduke Langdale (the English Royalist commander in the north west).[6]

As the English Royalist uprisings were close to collapse, it was on the adventures of the Engager Scottish army that the interest of the war centred. It was by no means the veteran army of the Earl of Leven, which had long been disbanded. For the most part it consisted of raw levies and, as the Kirk Party had refused to sanction The Engagement (an agreement between Charles I and the Scots Parliament for the Scots to intervene in England on behalf of Charles), David Leslie and thousands of experienced officers and men declined to serve. The leadership of the Duke of Hamilton proved to be a poor substitute for that of Leslie. Hamilton's army, too, was so ill provided that as soon as England was invaded it began to plunder the countryside for the bare means of sustenance.[5]

On 8 July the Scots, with Langdale as advanced guard, were about Carlisle, and reinforcements from Ulster were expected daily. Lambert's horse were at Penrith, Hexham and Newcastle, too weak to fight and having only skilful leading and rapidity of movement to enable them to gain time.[6]

Appleby Castle surrendered to the Scots on 31 July, whereat Lambert, who was still hanging on to the flank of the Scottish advance, fell back from Barnard Castle to Richmond so as to close Wensleydale against any attempt of the invaders to march on Pontefract. All the restless energy of Langdale's horse was unable to dislodge Lambert from the passes or to find out what was behind that impenetrable cavalry screen. The crisis was now at hand. Cromwell had received the surrender of Pembroke Castle on 11 July, and had marched off, with his men unpaid, ragged and shoeless, at full speed through the Midlands. Rains and storms delayed his march, but he knew that Hamilton in the broken ground of Westmorland was still worse off. Shoes from Northampton and stockings from Coventry met him, at Nottingham, and, gathering up the local levies as he went, he made for Doncaster, where he arrived on 8 August, having gained six days in advance of the time he had allowed himself for the march. He then called up artillery from Hull, exchanged his local levies for the regulars who were besieging Pontefract, and set off to meet Lambert.

On 12 August Cromwell was at Wetherby, Lambert with horse and foot at Otley, Langdale at Skipton and Gargrave. Hamilton was at Lancaster, and Sir George Monro with the Scots from Ulster and the Carlisle Royalists (organized as a separate command owing to friction between Monro and the generals of the main army) at Hornby.

On 13 August, while Cromwell was marching to join Lambert at Otley, the Scottish leaders were still disputing whether they should make for Pontefract or continue through Lancashire so as to join Lord Byron and the Cheshire Royalists.[6]

Battle

On 14 August 1648 Cromwell and Lambert were at Skipton, on 15 August at Gisburn and on 16 August they marched down the valley of the Ribble towards Preston with full knowledge of the enemy's dispositions and full determination to attack him. They had with them horse and foot not only of the Army, but also of the militia of Yorkshire, Durham, Northumberland and Lancashire, and withal were slightly outnumbered, having only 8,600 men against perhaps 9,000 of Hamilton's command. But the latter were scattered for convenience of supply along the road from Lancaster, through Preston, towards Wigan, Langdale's corps having thus become the left flank guard instead of the advanced guard.[7]

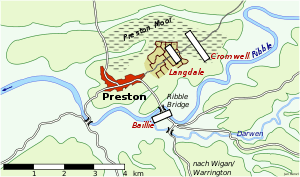

Langdale called in his advanced parties, perhaps with a view to resuming the duties of advanced guard, on the night of 13 August, and collected them near Longridge. It is not clear whether he reported Cromwell's advance, but, if he did, Hamilton ignored the report, for on 17 August Monro was half a day's march to the north, Langdale east of Preston, and the main army strung out on the road to Wigan, Major-General William Baillie with a body of foot, the rear of the column, being still in Preston. Hamilton, yielding to the importunity of his lieutenant-general, James Livingston, 1st Earl of Callendar, sent Baillie across the Ribble to follow the main body just as Langdale, with 3,000 foot and 500 horse only, met the first shock of Cromwell's attack on Preston Moor. Hamilton, like Charles at Edgehill, passively shared in, without directing, the Battle of Preston, and, though Langdale's men fought magnificently, they were after four hours' struggle driven to the Ribble.[7]

Baillie attempted to cover the Ribble and Darwen bridges on the Wigan road, but Cromwell had forced his way across both before nightfall. Pursuit was at once undertaken, and not relaxed until Hamilton had been driven through Wigan and Winwick to Uttoxeter and Ashbourne. There, pressed furiously in rear by Cromwell's horse and held up in front by the militia of the midlands, the remnant of the Scottish army laid down its arms on 25 August. Various attempts were made to raise the Royalist standard in Wales and elsewhere, but Preston was the death-blow to the Royalist hopes in the Second Civil War.[7]

Cromwell estimated the Royalist losses at 2,000 killed and 9,000 captured.[2] Those among the prisoners who had served voluntarily were bound for servile labour in the New World, and when there was no more demand there, for service in the Republic of Venice [8] When the English Parliament decreed a day of thanksgiving for the victory, it was announced that Cromwell's army had "one hundred at the most" killed.[3]

In Literature

The Battle of Preston is depicted in Robert Neil's historical novel "Witch Bane". As noted by Neil in his historical note, it is difficult to reconstruct with certainty precisely where in Preston the battle took place. The only contemporary accounts with much authority are those of Sir Marmaduke Langdale and of Cromwell in his letter to Mr. Speaker Lenthall. Both accounts are weak on topography, since neither of the military commanders knew the ground.

Neil's protagonists are two women, caught up in the fighting, desperately trying to survive while also deeply worried about their respective lovers who are fighting on opposing sides. The topography is crucial to the plot's depiction of the women trying to escape the fighting. Before writing, Neil studied extensively the existing sources and walked repeatedly around the battleground. What Cromwell described as "A lane, very deep and ill, up to the Enemy's army and leading to the Town" is also mentioned by Sir Marmaduke, who blames his Scottish allies for having failed to secure that lane, whose eventual capture enabled the Parliamentary forces to outflank the Royalists. Neil's plot and the route taken by his protagonists is based on the assumption that this crucial lane followed more or less the line of the present A59 road through Brockholes to Blackburn. Neil concedes, however, that other interpretations of the battle's topography are possible. (Quotes from Neil's historical note are from Robert Neil, "Witch Bane", Arrow Books, London 1968.)

References

- Bull, Stephen; Seed, Mike (1998). Bloody Preston: The Battle of Preston, 1648. Lancaster: Carnegie Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-85936-041-6.

- Braddick, God's Fury, England's Fire, p. 543. Braddick cites 21.000 as the contemporary figure given in pamphlets, but considers 9000 to be closer to the truth.

- Bull and Seed, p. 100

- Bull and Seed, p. 101

- David Plant. 1648: The Preston Campaign, British Civil Wars & Commonwealth website. Accessed 29 May 2008

- Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition article GREAT REBELLION; 47. Lambert in the north

- Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition article GREAT REBELLION; 48. Campaign of Preston

- Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition article GREAT REBELLION; 49. Preston Fight

- Michael Braddick, God's Fury England's Fire: A New History of the English Civil Wars, London, Allen Lane, 2008, p.545

- Attribution

Further reading

- Bell, Robert (2008) [1849]. Memorials of the Civil War. II. READ BOOKS. pp. 60–64. ISBN 1-4097-6468-0. Sir Marmaduke Langdale's letter (26 August 1648) and an account of his capture extracted from Memoirs Of The Life Of Colonel Hutchinson by Lucy Hutchinson.

- Carlyle, Thomas, ed. (1846). Oliver Cromwell's letters and speeches: with Elucidations by Thomas Carlyle. Volume 1 of 3. Chapman and Hall. pp. 359–379.. "There are four accounts of this [battle] by eye-witnesses, still accessible: Cromwell's account in these Two Letters; a Captain Hodgson's rough brief recollections written afterwards; and on the other side, Sir Marmaduke Langdale's Letter in vindication of his conduct there; and lastly the deliberate Narrative of Sir James Turner."

- Braddick, Michael (2009). God's Fury, England's Fire. Penguin Books..

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |