Battle of Montgomery's Tavern

The Battle of Montgomery's Tavern was an incident in the Upper Canada Rebellion. The abortive revolutionary insurrection inspired by William Lyon Mackenzie was crushed by British authorities and Canadian volunteer units near a tavern on Yonge Street, Toronto.

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Toronto | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Events | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Other | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

The site of Montgomery's Tavern was designated a National Historic Site in 1925.[1][2]

Prelude

When the Lower Canada Rebellion broke out in the fall of 1837, Sir Francis Bond Head sent the British troops stationed in Toronto (formerly York) to help suppress it. With the regular troops gone, William Lyon Mackenzie and his followers seized a Toronto armoury and organized an armed march down Yonge Street, beginning at Montgomery's Tavern (on Yonge St just north of Eglinton Avenue – the present-day site of Postal Station K) on December 4, 1837.

While marching down Yonge Street, Mackenzie and some fellow rebels encountered John Powell and Archibald McDonald while attempting to scout the city. Upon meeting them, Mackenzie took Powell prisoner and sent them to Montgomery's Tavern. Although there were concerns over whether Powell and McDonald possessed arms, Mackenzie accepted their denials and said, "well, gentlemen, as you are my townsmen, and men of honor, I would be ashamed to show that I question your words by ordering you to be searched."[3] Despite such assurances, Powell had hidden a pistol and shot rebel Captain Anthony Anderson before escaping back to Toronto, thereby dealing a large blow to the rebel's military expertise.[4]

Colonel Robert Moodie attempted to lead a force of loyalists through the rebel roadblock to warn Governor Bond Head in Toronto. Moodie fired his pistol, apparently in an attempt to clear the way. A number of the rebels returned fire, killing him.[5]

On the same day, December 5, Mackenzie's approximately 500 rebels marched upon Toronto's city hall in an effort to seize the arms and ammunition that were stored there. As Mackenzie and his forces marched towards Toronto, Bond Head sent a flag of truce and asked for their demands, to which Mackenzie demanded "Independence and a convention to arrange details." By the time Mackenzie and his followers had reached College Street, Bond Head sent another party to tell Mackenzie that his demands had been rejected.[6]

Later that afternoon, Mackenzie led his troops farther down Yonge Street towards the city, where their advance was stopped by a party of 27 loyalist volunteers, led by William Botsford Jarvis. The two sides exchanged gunfire. Jarvis' loyalist troops fired a volley at Egmond's gang and dropped to reload. Thinking the loyalist soldiers had been killed, Van Egmond gave the order to charge and in the ensuing melee many of the rebel soldiers fled or deserted the group.[7] That night, reinforcements for the loyalists arrived from Hamilton. By the next day, these forces were 1,500 strong.

The last real engagement prior to the Battle of Montgomery's Tavern occurred on December 6 via a raid on a mail coach which was suspected to have government intelligence regarding future actions towards the rebels. It was from this raid that the rebels learned of government plans to soon attack Montgomery's Tavern.[8]

Montgomery's Tavern

The rebels, now under the command of Napoleonic Wars veteran Anthony Van Egmond, had regrouped at Montgomery's Tavern. One hundred and fifty were posted in the woods behind the tavern (on the west side of Yonge Street) and another 60 took up positions behind a line of rail fencing (on the East side of Yonge Street). The majority of Mackenzie's supporters, numbering about 300, were gathered around the tavern proper. These were largely unarmed and would offer little resistance when pressed.

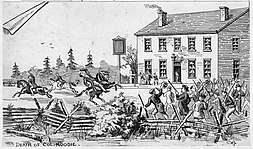

On December 7, Colonel James Fitzgibbon marched an estimated 1,000 regulars and militiamen up Yonge Street and attacked Mackenzie's force at Montgomery's Tavern, putting the building under artillery fire.[9] When Fitzgibbon advanced his infantry, both parties of rebels abandoned their posts and retreated in disarray to the tavern, causing those assembled there to panic and flee. Within 20 minutes, the rebels were gone. Loyalist forces then looted the tavern and burned it to the ground, before marching back to York.

Post rebellion and site today

Following the rebellion, the site of the tavern was used to build a hotel, with the structure of the old Davisville Hotel.[10] In 1858 it was sold to hotelier Charles McBride of Willowdale (1832–?), who renamed the tavern Prospect House.[11] The tavern would serve as Masonic Lodge and North Toronto township council office. McBride sold the hotel in 1873 to build another hotel, Bedford Park Hotel, on Yonge Street. Prospect House burned down in 1881, and the vacant land was sold to proprietor (and later as hotelier) John Oulcott of Toronto, who rebuilt a three-storey Oulcott's Hotel (Eglinton House) in 1883.[12] Oulcott sold out in 1912 and the hotel went to various owners. In 1913, the federal government purchased the hotel and remodelled the old hotel as a post office for the North Toronto postal district.[13] It was finally torn down in the 1930s to be replaced by the current structure.[12] The site of the tavern is now occupied by a two-storey Art Deco post office designed by Murray Brown and built in 1936. The building, Postal Station K, bears the cypher EviiiR, for Edward VIII, King of Canada for eleven months in 1936; it is one of a few buildings to bear this mark in Toronto. As of spring 2016, construction is underway to incorporate the post office into a new building which will include retail space and podium for the 27-storey Montgomery Square luxury rental apartment building.

References

- "Montgomery's Tavern National Historic Site of Canada". www.pc.gc.ca. Retrieved December 8, 2018., Directory of Designations of National Historic Significance of Canada.

- Montgomery's Tavern. Canadian Register of Historic Places.

- Mackenzie, William Lyon. Mackenzie's Own Narrative of the Late Rebellion, With Illustrations and Notes, Critical and Explanatory: Exhibiting the Only True Account of What Took Place at the Memorable Siege of Toronto in the Month of December of 1837. Toronto: Pallandium Office, 1838. Pg. 9-10, https://archive.org/stream/cihm_34462#page/n5/mode/1up.

- Read, D.B. The Canadian Rebellion of 1837. Toronto: C. Blackett Robinson, 1896. Pg. 303-304.

- Wrong, George M.; Langton, H. H. (2009). The Chronicles of Canada: Volume VII – The Struggle for Political Freedom. Fireship Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-934757-50-5. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- Lindsey, Charles. The Life and Times of William Lyon Mackenzie; With an Account of the Canadian Rebellion of 1837, and the Subsequent Frontier Disturbances, Chiefly from Unpublished Documents. Volume II. Toronto: P.R. Randall, 1862. Pg. 81-86. https://archive.org/stream/lifetimesofwilli02linduoft#page/n7/mode/2up.

- "A brief history of the Battle of Montgomery's Tavern". www.blogto.com.

- Lindsey, Charles. The Life and Times of William Lyon Mackenzie; With an Account of the Canadian Rebellion of 1837, and the Subsequent Frontier Disturbances, Chiefly from Unpublished Document. Volume II. Toronto: P.R. Randall, 1862. Pg. 91. https://archive.org/stream/lifetimesofwilli02linduoft#page/n7/mode/2up.

- "December 7, 1837: Battle of Montgomery's Tavern". Toronto Star, Brennan Doherty, Dec. 2, 2016

- Jackes, Lyman B. "The Building That Rose From the Ruins of the Famous Montgomery's Tavern". Tales of north Toronto. 2. Toronto: Canadian Historical Press. p. 11.

- Mulvany, Charles Pelham; Adam, Graeme Mercer (1885). History of Toronto and county of York, Ontario. C.B. Robinson. p. 229. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- Berchem, F.R. (1996). Opportunity Road: Yonge Street 1860-1939. Toronto: Natural Heritage/Natural History. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-4597-1337-6. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- "North Toronto's New Post Office". The Toronto World. September 8, 1913. p. 3. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

External links

- Upper Canada, The Confrontation at Montgomery's Tavern

- Colonel Moodie Rides Down Yonge Street

- Statement of proceedings in Toronto against MacKenzie's mob of assassins, prepared for the Upper Canada Herald by three gentlemen who were eye-witnesses, 1837

- Review of Mackenzie's publications on the revolt before Toronto, in Upper Canada, 1838