Battle of Lechfeld

The Battle of Lechfeld[1] was a series of military engagements over the course of three days from 10–12 August 955 in which the German forces of King Otto I the Great annihilated a Hungarian army led by harka Bulcsú and the chieftains Lél and Súr. With this German victory, further invasions by the Magyars into Latin Europe were ended.

| Second Battle of Lechfeld | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hungarian invasions of Europe | |||||||

The Battle of Lechfeld, from a 1457 illustration in Sigmund Meisterlin's codex of Nuremberg history | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

King Otto I Duke Conrad the Red (Franconia) † Duke Burchard III (Swabia) Duke Boleslaus (Bohemia) |

horka Bulcsú Lél Súr Taksony | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

7,000–9,000 heavy cavalry Garrison |

8,000–10,000 horse archers Infantry Siege engines | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Heavy | Majority killed | ||||||

The Hungarians invaded the Duchy of Bavaria in late June or early July 955 with 8,000–10,000 horse archers, infantry, and siege engines, intending to draw the main German army under Otto into battle in the open field and destroy it. The Hungarians laid siege to Augsburg on the Lech river. Otto advanced to relieve the city with an army of 8,000 heavy cavalry, divided into eight legions.

As Otto approached Augsburg on 10 August, a Hungarian surprise attack destroyed Otto's Bohemian rearguard legion. The Hungarian force stopped to plunder the German camp and Duke Conrad the Red of Lorraine led a counter-attack with heavy cavalry, dispersing the Hungarians. Otto then brought his army into battle against the main Hungarian army that barred his way to Augsburg. The German heavy cavalry defeated the lightly armed and armored Hungarians in close combat, but the latter retreated in good order. Otto did not pursue, returning to Augsburg for the night and sending out messengers to order all local German forces to hold the river crossings in Eastern Bavaria and prevent the Hungarians from returning to their homeland. On 11 and 12 August, the Hungarian defeat was transformed into disaster, as heavy rainfall and flooding slowed the retreating Hungarians and allowed German troops to hunt them down and kill them all. The Hungarian leaders were captured, taken to Augsburg and hanged.

The German victory preserved the Kingdom of Germany and halted nomad incursions into Western Europe for good. Otto was proclaimed emperor and father of the fatherland by his army after the victory and he went on to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 962 largely on the basis of his strengthened position after Lechfeld.

Sources

Perhaps the most important source is Gerhard's monograph Vita Sancti Uodalrici, which describes the series of actions from the German point of view.[2] Another source is the chronicler Widukind of Corvey, who provides some important details.[3]

Background

After having put down a rebellion by his son, Liudolf, Duke of Swabia and son-in-law, Conrad, Duke of Lorraine, Otto I the Great, King of East Francia, set out to Saxony, his duchy. In early July he received Hungarian legates, who claimed to come in peace, but whom the Germans suspected were actually assessing the outcome of the rebellion.[4] After a few days, Otto let them go with some small gifts.[4]

Soon, couriers from Otto's brother Henry I, Duke of Bavaria, arrived to inform Otto in Magdeburg of a Hungarian invasion.[4] The couriers added that the Hungarians were seeking a battle with Otto.[4] The Hungarians had already invaded once before during the course of the rebellion.[5] This occurred immediately after he had put down a revolt in Franconia. Because of unrest among the Polabian Slavs on the lower Elbe, Otto had to leave most of his Saxons at home.[4] In addition, Saxony was distant from Augsburg and its environs, and considerable time would have elapsed waiting for their arrival.[5] The battle took place six weeks after the first report of an invasion, and historian Hans Delbrück asserts that they could not have possibly made the march in time.[6]

The King ordered his troops to concentrate on the Danube, in the vicinity of Neuburg and Ingolstadt.[4] He did this in order to march on the Hungarian line of communications and catch them in their rear while they were raiding northeast of Augsburg. It was also a central point of concentration for all the contingents that were assembling. Strategically, therefore, this was the best location for Otto to concentrate his forces before making the final descent upon the Hungarians.[7]

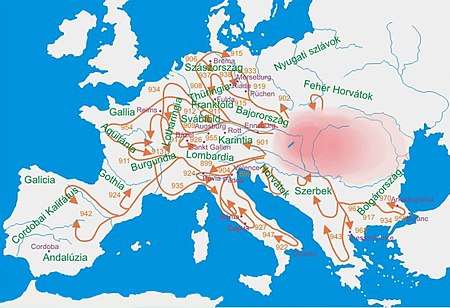

There were other troops that had an influence on the course of the battle. On previous occasions, in 932 and 954 for example, there had been Hungarian incursions that had invaded the German lands to the south of the Danube, and then retreated back to their native country via Lotharingia, to the West Frankish Kingdom and finally, through Italy. That is to say, a wide sweeping U-turn that initially started westward, then progressed to the south, and then finally to the east back to their homeland; and thus escaping retribution in German territory. The King was aware of the escape of these Hungarians on the above-mentioned occasions, and was determined to trap them. He therefore ordered his brother, Archbishop Bruno, to keep the Lotharingian forces in Lotharingia.[8] With a powerful force of knights pressing them from the west, and an equally strong force of knights chasing them from the east, the Hungarians would be unable to escape.[8]

Located south of Augsburg, the Lechfeld is the flood plain that lies along the Lech River. The battle appears as the second Battle of Augsburg in Hungarian historiography.[9] The first Battle of Lechfeld happened in the same area forty-five years earlier.[10]

Prelude

Gerhard writes that the Hungarian forces advanced across the Lech to the Iller River and ravaged the lands in between.[2] They then withdrew from the Iller and placed Augsburg, a border city of Swabia, under siege.[2] Augsburg had been heavily damaged during a rebellion against Otto in 954.[2] The city was defended by Bishop Ulrich.[2] He ordered his contingent of soldiers to not fight the Hungarians in the open and reinforce the main south gate of the fortress instead. He motivated them with the 23rd Psalm ("Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death"). While this defense was going on, the King was raising an army to march south.[5][2] A major action took place on 8 August at the eastern gate, which the Hungarians tried to storm in large numbers.[2] Ulrich led his professional milites soldiers out into the field to engage the enemy in close combat.[2] Ulrich was unarmed, wearing only a stola while mounted on a warhorse.[11] The soldiers killed the Hungarian commander, forcing the Hungarians to withdraw to their camp.[3]

On 9 August the Hungarians attacked with siege engines and infantry, who were driven forward by the whips of the Hungarian leaders.[3] During the battle, Berchtold of Risinesburg arrived to deliver word of the approach of the German army.[3] At the end of the day, the siege was suspended, and the Hungarian leaders held a war council.[3][12] The Hungarians decided to destroy Otto's army, believing that all of Germany would fall to them as a result.[3] As the Hungarians departed, Count Dietpald used the opportunity to lead soldiers to Otto's camp during the night.[3]

Opposing forces

According to Widukind, Otto had at his disposal eight legiones (divisions) included three from Bavaria, two from Swabia, one from Franconia under Duke Conrad and one well-trained legion from Bohemia, under a prince of an unknown name, son of Boleslaus I.[13][14] The eighth division, commanded by Otto, and slightly larger than the others, included Saxons, Thuringians, and the King's personal guard, the legio regia.[4] The King's contingent consisted of hand-picked troops.[4] A late Roman legion had 1,000 men, so Otto's army may have numbered 7,000–9,000 troops.[13][15] Augusburg was defended by professional milites soldiers.[2]

The Hungarian plain's grasslands could sustain the mounts of up to 15,000 horse archers, but more likely the Hungarians only had 8,000–10,000.[16][17] The Hungarian army also included some poorly equipped and hesitant infantry as well as siege engines.[3][18]

Battle

On 9 August, the German scouts reported that the Hungarian army was in the vicinity.[4] Otto deployed his army for battle the next day.[4] The order of march of the German army was as follows: the three Bavarian contingents, the Frankish contingent under Duke Konrad, the royal unit (the center), the two contingents of Swabians and the Bohemian contingent guarding the supply train in the rear.[14] The Bavarians were placed at the head of column, according to Delbrück, because they were marching through Bavarian territory and they therefore knew the territory best. All of these were mounted.[7] The German army marched through woodland that protected them from the Hungarian arrowstorm but also made it more difficult to see the Hungarian movements.[19]

According to the chronicler Widukind of Corvey, Otto "pitched his camp in the territory of the city of Augsburg and joined there the forces of Henry I, Duke of Bavaria, who was himself lying mortally ill nearby, and by Duke Conrad with a large following of Franconian knights. Conrad's unexpected arrival encouraged the warriors so much that they wished to attack the enemy immediately."[20]

The arrival of Conrad, the exiled Duke of Lotharingia (Lorraine), and Otto's son-in-law, was particularly heartening because he had recently thrown in his lot with the Magyars, but now returned to fight under Otto; in the ensuing battle he lost his life. A legion of Swabians was commanded by Burchard III, Duke of Swabia, who had married Otto's niece Hedwig. Also among those fighting under Otto was Boleslav of Bohemia. Otto himself led the legio regia, stronger than any of the others in both numbers and quality.[4]

The main Hungarian army blocked Otto's way to Augsburg.[23] A contingent of Hungarian horse-archers crossed the river west of Augsburg and immediately attacked the Bohemian legion from the flank.[24] The Bohemians were routed and the two Swabian legions were badly damaged.[24] The Hungarians stopped to plunder the German baggage train and Duke Conrad the Red used the opportunity to attack the vulnerable Hungarians and shatter them.[24][19] Conrad returned to Otto with captured Hungarian banners.[24] Conrad's victory prevented the German army from being encircled.[25]

Otto rallied his men with a speech in which he claimed the Germans had better weapons than the Hungarians.[25] Otto then led the German army into battle with the main Hungarian force, defeating them.[25] The Hungarians were cut to pieces in numerous small encounters.[19] Seeing the day going against them, the Hungarians retreated in ordered formations across the Lech to the east.[3] Otto's army pursued, killing every captured Hungarian.[3] The Germans took the Hungarian camp, liberating prisoners and reclaiming booty.[25]

The King spent the night after the battle in Augsburg.[7] On 11 August he specifically issued the order that all river crossings were to be held.[8][4] This was done so that as many of the Hungarians as possible, and specifically their leaders, could be captured and killed.[4] This strategy was successful, as Duke Henry of Bavaria captured a number of their leaders and killed them.[4][26] Some Hungarians tried to flee across an unknown river but were swept away by a torrent.[25] The destruction of the Hungarian army continued on 12 August, with heavy rainfall and flooding allowing German troops operating from nearby fortifications to kill all or almost all of the fleeing Hungarian soldiers.[25][18]

The captured Magyars were either executed, or sent back to their ruling prince, Taksony, missing their ears and noses. The Hungarian leaders Lél, Bulcsú and Súr, who were not Árpáds, were executed after the battle.[27] Duke Conrad was also killed, after he loosened his mail armour in the summer heat and one arrow struck his throat.[28]

Aftermath

Upon destruction of the Hungarian forces, the German army proclaimed Otto father of the fatherland and emperor.[28] In 962, on the strength of this, Otto went to Rome and had himself crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope John XII.[29]

The Hungarian leaders Bulcsú, Lehel and Súr were taken to Regensburg and hanged with many other Hungarians.[4]

The German annihilation of the Hungarian army definitively ended the attacks of Magyar nomads against Latin Europe.[19] The Hungarian historian Gyula Kristó calls it a "catastrophic defeat".[30] After the defeat, the Hungarians reached the end of the almost 100-year era in which they were seen as the dominating military force in Europe.[31]

After 955, the Hungarians completely ceased all campaigns westwards. In addition, Otto did not launch any further military campaigns against the Hungarians. The Hungarian leader Fajsz was dethroned following the defeat, and was succeeded as Grand Prince of the Hungarians by Taksony.[32]

Analysis

The battle has been viewed as a symbolic victory for the knightly cavalry, who would define European warfare in the High Middle Ages, over the nomadic, light cavalry that characterized warfare during the Early Middle Ages in Central and Eastern Europe.[33]

Paul K. Davis writes, the "Magyar defeat ended more than 90 years of their pillaging western Europe and convinced survivors to settle down, creating the basis for the state of Hungary."[34]

References

Citations

- Baron Edward Francis Twining Twining, A history of the crown jewels of Europe, B. T. Batsford, 1960, p. 387

- Bowlus 2016, p. 9.

- Bowlus 2016, p. 10.

- Bowlus 2016, p. 11.

- Delbrück 1982, p. 115.

- Delbrück 1982, p. 116.

- Delbrück 1982, p. 118.

- Delbrück 1982, p. 122.

- György Szabados, A magyar történelem kezdeteiről: az előidő-szemlélet hangsúlyváltásai a XV-XVIII. században, Balassi K., 2006, p. 134

- Bowlus 2016, p. 166.

- Bowlus 2016, pp. 9–10.

- Delbrück 1982, p. 678.

- Bowlus 2016, p. 120.

- Bowlus 2016, pp. 11–12.

- Beeler, p 229. The author gives no figures for the Magyars.

- Bowlus 2016, p. 27.

- Bowlus 2016, p. 78.

- Bowlus 2016, p. 172.

- Bowlus 2016, p. 170.

- http://college.hmco.com/history/west/mosaic/chapter5/source259.html (paid account required)

- Sepp, Johann Nepomuk (1903). Ludwig Augustus, König von Baÿern: und das Zeitalter der Wiedergeburt der Künste (in German). Manz. p. 561.

- Schöneck, Annette (2018-12-18). Literarische Geschichtsbilder: Anschauliches Erzählen im historischen Roman 1855-1887 (in German). Ergon Verlag. pp. 175, 377, 382. ISBN 9783956504587.

- Bowlus 2016, pp. 12–13.

- Bowlus 2016, p. 12.

- Bowlus 2016, p. 13.

- Delbrück 1982, p. 123.

- Pal Engel and Andrew Ayton, The Realm of St Stephen: History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526, (I.B. Tauris, 2001), 14–15.

- Bowlus 2016, p. 181.

- Bowlus 2016, p. 5.

- Kristó, Gyula; Makk, Ferenc (1996). Az Árpád-ház uralkodói [Rulers of the House of Árpád] (in Hungarian). I.P.C. Könyvek, p. 23. - One may ask why the Hungarians abruptly ended their century old-tradition of raiding western Europe after that battle if it was insignificant.

- Bóna István (March 2000). "A kalandozó magyarság veresége. A Lech-mezei csata valós szerepe" (in Hungarian). Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-09.

- Miklós Molnár, A concise history of Hungary, Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 17

- Archer, Christon I.; Ferris, John R.; Herwig, Holger H.; Timothy H. E. Travers (2008-09-01). World History of Warfare. Univ of Nebraska Pr. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-8032-1941-0. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- Davis, Paul K. (2001-04-15). 100 Decisive Battles: from Ancient Times to the Present. Oxford University Press US. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-19-514366-9. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

Works consulted

- Beeler, John (December 1973). Warfare in Feudal Europe, 730–1200. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9120-7.

- Bowlus, Charles R. (2016) [2006]. The Battle of Lechfeld and its Aftermath, August 955: the End of the Age of Migrations in the Latin West. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7546-5470-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Delbrück, Hans (1982) [1923]. History of the Art of War, Volume Three: Medieval Warfare. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-6585-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Platschka, Alfred. "Die Schlacht auf dem Lechfeld" (in German). Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-09.

- Widukind of Corvey. The Deeds of the Saxons

- Weir, William (2009). 50 Battles That Changed the World: The Conflicts That Most Influenced the Course of History. Savage, MD: Barnes and Noble Books. ISBN 0-7607-6609-6.