Battle of Johnsonville

The Battle of Johnsonville was fought November 4–5, 1864, in Benton County, Tennessee and Humphreys County, Tennessee, during the American Civil War. Confederate cavalry commander Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest culminated a 23-day raid through western Tennessee by attacking the Union supply base at Johnsonville. Forrest's attack destroyed numerous boats in the Tennessee River and millions of dollars of supplies, disrupting the logistical operations of Union Major General George H. Thomas in Nashville. As a result, Thomas's army was hampered in its (eventually successful) plan to defeat Confederate Lieutenant General John Bell Hood's invasion of Tennessee, the Franklin-Nashville Campaign.

| Battle of Johnsonville | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Charles R. Thompson Edward M. King | Nathan Bedford Forrest | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Johnsonville garrison | Forrest's Cavalry Division | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

4,000 3 gunboats | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 150 captured[1] |

2 killed 9 wounded[1] | ||||||

Background

One of the critical routes used to supply the Federal forces in Tennessee was the Tennessee River. Supplies were offloaded at Johnsonville and then shipped by rail to Nashville. In the fall of 1864 the supplies were principally meant for the Army of the Cumberland, commanded by Thomas. Meanwhile, Hood's army was marching through northern Alabama on its way to an invasion of Tennessee. In late September 1864, Hood's army departed northwest from the vicinity of Atlanta, Georgia hoping its destruction of Union supply lines would lure Major General William T. Sherman's Union army into battle. Sherman pursued Hood as far as Gaylesville, Alabama, but decided to return his army to Atlanta and conduct instead a March to the Sea through Georgia. He gave responsibility for the defense of Tennessee to Thomas.[2]

_(14576310149).jpg)

Lieutenant General Richard Taylor ordered Forrest on a wide-ranging cavalry raid through Western Tennessee to destroy the Union supply line to Nashville. Forrest's initial objective was Fort Heiman[3] on the Tennessee River north of Johnsonville, possession of which would prevent Union transports from reaching Johnsonville, upriver. The first of Forrest's men began to ride on October 16, 1864. They were exhausted from a previous raid and Forrest gave them orders to disperse, obtain new mounts and supplies, and return to the raid. Forrest himself began moving north on October 24 and reached Fort Heiman on October 28, where he emplaced artillery. On October 29 and October 30, his artillery fire caused the capture of the steamers Mazeppa, Anna, and Venus, as well as the gunboat Undine. At this point, the Union stopped river supply traffic to Johnsonville.[4]

Forrest repaired two of the boats, Undine and Venus, to use as a small flotilla to aid in his attack on Johnsonville. The boats and his cavalrymen departed on November 1, 1864, while the land component of his expedition encountered difficult road conditions following recent rains. On November 2, Forrest's flotilla was challenged by two Union gunboats, Key West and Tawah, and Venus was run aground and captured. The Federals dispatched six more gunboats from Paducah, Kentucky, and on November 3 they engaged in artillery duels with strong Confederate positions on either end of Reynoldsburg Island, near Johnsonville. The Federal fleet had difficulty attempting to subdue these positions and were occupied as Forrest prepared his force for the attack on Johnsonville.[5]

Battle

On the evening of November 3, 1864, Forrest's artillerist, Capt. John Morton, positioned his guns across the river from the Federal supply base at Johnsonville. On the morning of November 4, Undine and the Confederate batteries were attacked by three Union gunboats from Johnsonville under U.S. Navy Lt. Edward M. King and by the six Paducah gunboats under Lt. Cmdr. LeRoy Fitch. Capt. Frank M. Gracey (a former steamboat captain now serving as a Confederate cavalryman) abandoned Undine, setting her on fire, which caused her ammunition magazine to explode, ending Forrest's brief career as a naval commander. Despite this loss, the Confederate land artillery was completely effective in neutralizing the threat of the Federal fleets. Fitch was reluctant to take his Paducah gunboats through the narrow channel between Reynoldsburg Island and the western bank, so limited himself to long-range fire. King withered under the Confederate fire, which hit one of his vessels 19 times, and returned to Johnsonville.[6]

Capt. Morton's guns bombarded the Union supply depot and the 28 steamboats and barges positioned at the wharf. All three of the Union gunboats—Key West, Tawah, and Elfin—were disabled or destroyed.[7] The Union garrison commander ordered that the supply vessels be burned to prevent their capture by the Confederates. Forrest observed, "By night the wharf for nearly one mile up and down the river presented one solid sheet of flame. ... Having completed the work designed for the expedition, I moved my command six miles during the night by the light of the enemy's burning property."[8]

Aftermath

Forrest caused enormous damage at very low cost. He reported only 2 men killed and 9 wounded. He described the Union losses as 4 gunboats, 14 transports, 20 barges, 26 pieces of artillery, $6,700,000 worth of property, and 150 prisoners. One Union officer described the monetary loss as about $2,200,000. An additional consequence of the raid was that the Union high command became increasingly nervous about Sherman's plan to move through Georgia instead of confronting Hood and Forrest directly. Forrest's command, delayed by heavy rains, proceeded to Perryville, Tennessee, and eventually reached Corinth, Mississippi, on November 10, 1864. During the raid, on November 3, Confederate theater commander Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard designated Forrest's cavalry for assignment to Hood's Army of Tennessee for the Franklin–Nashville Campaign. Hood elected to delay his advance from Tuscumbia, Alabama, north into Tennessee, until Forrest was able to link up with him there on November 16.[9]

Legacy

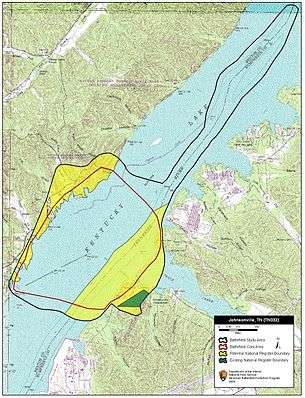

The Battle of Johnsonville is now the focus of two Tennessee state parks: Nathan Bedford Forrest State Park, which is situated on the Benton County side of the river, and Johnsonville State Historic Park, which is situated on the Humphreys County side. The Civil War Trust (a division of the American Battlefield Trust) and its partners have acquired and preserved 19 acres (0.077 km2) of the battlefield.[10]

Notes

- Wills, p. 272.

- Kennedy, p. 389; Eicher, p. 770.

- Fort Heiman was captured by the Union Army in conjunction with the Battle of Fort Henry in February 1862.

- Wills, pp. 263–65.

- Wills, pp. 265–69.

- Wills, pp. 268–70.

- Library of Congress- A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 – 1875

- Wills, pp. 270–73; Kennedy, p. 389.

- Wills, pp. 272–73; Sword, pp. 67–68; Nevin, p. 34; Eicher, p. 769; Kennedy, p. 389.

- American Battlefield Trust "Saved Land" webpage. Accessed May 25, 2018.

References

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- Nevin, David, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. Sherman's March: Atlanta to the Sea. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1986. ISBN 0-8094-4812-2.

- Sword, Wiley. The Confederacy's Last Hurrah: Spring Hill, Franklin, and Nashville. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1993. ISBN 0-7006-0650-5. First published with the title Embrace an Angry Wind in 1992 by HarperCollins.

- Wills, Brian Steel. The Confederacy's Greatest Cavalryman: Nathan Bedford Forrest. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1992. ISBN 0-7006-0885-0.