Battle of Goose Green

The Battle of Goose Green was an engagement between British and Argentine forces on 28 and 29 May 1982 during the Falklands War. Located on East Falkland's central isthmus, the settlement of Goose Green was the site of an airfield. Argentine forces were in a well-defended position, within striking distance of San Carlos Water, where the British task force had made its amphibious landing.

The main body of the British assault force was the 2nd Battalion, Parachute Regiment (2 Para), commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert Jones. BBC radio broadcast news of the imminent attack on Goose Green. Knowing that this had likely forewarned the Argentinian defenders, the broadcast provoked immediate criticism from Jones and other British personnel.

After the attack began in the early hours of 28 May 1982, the 2nd Parachute Battalion advance was stalled by fixed trenches with interlocking fields of fire. Jones was killed during a solo charge on an enemy machine-gun post. The Argentinian garrison agreed to a ceasefire and formally surrendered the following morning. As a result of their actions, both Jones and his successor as commanding officer of the 2nd Parachute Battalion, Major Chris Keeble, were awarded medals: Jones received a posthumous Victoria Cross and Keeble received the Distinguished Service Order.

Prelude

Times and nomenclature

British forces kept Zulu time (UTC), and many news reports were dated accordingly. However, times on this page are according to local, Falkland Island time (UTC−3), the same as that kept in Argentina. On the day of the battle, sunrise was at 08:39 and sunset at 16:58.[7] To avoid confusion between similar company designations, Argentine companies are referred to in the form "Company A" while British forces are referred to as "A Company."

Terrain and conditions

Goose Green and Darwin are on a narrow isthmus connecting Lafonia, to the south, with Wickham Heights, to the north. The isthmus has two settlements, both on the eastern coast: Darwin, to the north, and Goose Green, to the south. The terrain is rolling and treeless and is covered with grassy outcrops, areas of thick gorse, and peat bogs, making effective camouflage and concealment extremely difficult.

The islands have a cold, damp climate. From May to August, winter in the southern hemisphere, the ground is saturated and frequently covered with salty water, making walking slow and exhausting, especially at night. Drizzly rains occur two out of every three days, with continuous winds. Periods of rain, snow, fog, and sun change rapidly, and sunshine is minimal, leaving few opportunities for troops to warm up and dry out.[8]

Operational purpose

The bulk of the Argentine forces were in positions around Port Stanley, about 50 miles (80 km) to the east of the isthmus and San Carlos, site of the main British landings. The Argentine positions at Goose Green and Darwin were well defended by a force equipped with artillery, mortars, 35 mm cannon, and machine guns.[9] British intelligence indicated that the Argentine force presented limited offensive capabilities and did not pose a major threat to the landing area at San Carlos. Consequently, Goose Green seemed to have no strategic military value for the British in their campaign to recapture the islands; and initial plans for land operations had called for Goose Green to be isolated and bypassed.[10]

After the British landings at San Carlos on 21 May and while the bridgehead was being consolidated, no offensive ground operations had been conducted and activities were limited to digging fortified positions, patrolling, and waiting;[11] during this time Argentine air attacks caused significant damage to, and loss of, British ships in the area around the landing grounds. These attacks and the lack of movement of the landed forces out of the San Carlos area, led to a feeling among senior commanders and politicians in the UK that the momentum of the campaign was being lost.[12] As a result, British Joint Headquarters in the UK came under increasing pressure from the British government for an early ground offensive, for its political and propaganda value.[13] If the Darwin–Goose Green isthmus could be taken before such a decision, British forces would control access to the entire Lafonia and thus a significant portion of East Falkland.[14] On 25 May Brigadier Julian Thompson, ground forces commander, commanding 3 Commando Brigade, was ordered to mount an attack on Argentine positions around Goose Green and Darwin.[12]

Argentinian defenses

The defending Argentine forces, known as Task Force Mercedes, consisted of two companies of Lieutenant-Colonel Ítalo Piaggi's 12th Infantry Regiment (RI 12)—his third company (Company B) was still deployed on Mount Kent as "Combat Team Solari" and was only to re-join RI 12 after the fall of Goose Green airfield.[15] The task force also contained a company of the ranger-type 25th Infantry Regiment (25th Special Infantry Regiment or RI 25).[16]

Air defense was provided by a battery of six 20 mm Rheinmetalls, manned by air force personnel, and two radar-guided Oerlikon 35 mm anti-aircraft guns from the 601st Anti-Aircraft Battalion, which would be employed in a ground support role in the last stages of the fighting. There was also one battery of three OTO Melara Mod 56 105 mm pack howitzers from the 4th Airborne Artillery Regiment. Pucará aircraft, based at Stanley and armed with rockets and napalm, provided close air support.[17] Total forces under Piaggi's command numbered 1,083 men.[18]

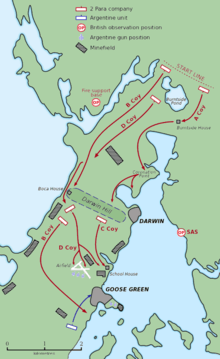

Piaggi's orders required him to provide a reserve battle group (Task Force Mercedes) in support of other forces deployed to the west of Stanley, to occupy and defend the Darwin isthmus, and to defend Military Air Base Condor located at Goose Green. He assumed an all-round defense posture, with Company A IR12 the key to his defense; they were deployed along a gorse hedge running across the Darwin isthmus from Darwin Hill to Boca House.[15] Piaggi deployed his recce platoon (under Lieutenant Carlos Marcelo Morales) as an advance screen forward of RI 12's A Company, towards Coronation Ridge, while RI 12's C Company were deployed south of Goose Green to cover the approaches from Lafonia. To substitute for B Company, which was kept on Mount Kent, he created a composite company from headquarters and other staff and deployed them in Goose Green. RI 25's C (Ranger) Company (under Paratroop-trained First Lieutenant Carlos Daniel Esteban) provided a mobile reserve. It was billeted at the schoolhouse in Goose Green.[15] Elements were also deployed to Darwin settlement, Salinas Beach, and Boca House; and the air force security cadets, together with the anti-aircraft elements, were charged with protecting the airfield. Minefields had been laid in areas deemed tactically important, to provide further defense against attack.[19]

On paper, Piaggi had a full regiment, but it consisted of units from three separate regiments from two different brigades, none of whom had ever worked together. RI 12 consisted mostly of conscripts from the northern, sub-tropical province of Corrientes, while RI 25 Company was considered an elite formation and had received commando training.[20] At the start of the battle, the Argentinian forces had about the same number of effective combatants as the British paratroopers.[21] Some elements were well trained and displayed a high degree of morale and motivation (C Company 25th Regiment and A Battery 4th Airborne Artillery Group); with Lieutenant Ignacio Gorriti of the 12th Regiment's B Company remarking that "there was no need for speeches. From the beginning, we knew how important the Malvinas were. It was a kind of love; we were going to defend something that was ours."[22][21] Other units were less well-motivated, with the 12th Regiment chaplain, Santiago Mora writing:

The conscripts of 25th Infantry wanted to fight and cover themselves in glory. The conscripts of the 12th Infantry Regiment fought because they were told to do so. This did not make them any less brave. On the whole, they remained admirably calm.[23]

Private Esteban Roberto Avalos fought in the Falklands as a sniper in RI 12's B Company. In all, some fifty hand-picked 12th Regiment conscripts and NCOs had received ranger training from visiting Halcón 8 (Falcon 8) army commandos in 1981, and then returned to their respective companies:

In my particular case, I ended up being a sharpshooter for which I had been preparing since the time we were out in the field, where I had the opportunity to shoot with a FAL. During the 45 days we spent there, we had to practice shooting three or four times a week, and those moments were taken advantage of to learn the shooting positions and familiarize ourselves with the weapon. The dealings with the superiors, in general, were excellent, although if somebody screwed up, we all paid the price. The most common punishments were taking us to the showers at night, forcing us to do push-ups or demand from us heaps of frog leaps and crawling. If someone took the wrong step, for example, it was reasonable to be pulled out of training, and they would make you 'dance' a little with push-ups on the thistles or the mud. Now, going back to the subject of instruction, I would say that it was generally satisfactory, at least as far as our group was concerned, since we had basic training in the use of explosives and we were even given some classes in self-defense."[24]

The Argentine positions were well selected, and officers well briefed.[21] In the weeks before the British invasion, airstrikes, naval bombardments, their own poor logistic support, and inclement conditions had contributed to its reduction,[25] Argentine morale remained strong among the 4th Airborne Artillery Regiment gunners present and the officers, NCOs, and ranger-trained conscripts of the 12th and 25th Regiments.[26]

British assault force

Thompson ordered 2nd Battalion of the Parachute Regiment (2 Para) to prepare for and execute an attack south, as they were the unit closest to the isthmus in the San Carlos defensive perimeter.[27] He ordered Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert 'H' Jones, the commanding officer of 2 Para, to "carry out a raid on Goose Green isthmus and capture the settlements before withdrawing to be in reserve for the main thrust to the north." The "capture" component appealed more to Jones than the "raid" component, although Thompson later acknowledged that he had assigned insufficient forces to rapidly execute the "capture" part of the orders.[28]

Two Para consisted of three rifle companies, one patrol company, one support company, and an HQ company. Thompson had assigned three 105 mm artillery pieces, with 960 shells, from 29 Commando Regiment, Royal Artillery; one MILAN anti-tank missile platoon; and Scout helicopters as support elements. Close air support was available from three Royal Air Force Harriers, and naval gunfire support was to be provided by HMS Arrow in the hours of darkness.[29]

An SAS survey had reported that the Darwin–Goose Green area was occupied by one Argentine company. Brigade intelligence reported that enemy forces consisted of three infantry companies (two from RI 12 and one from RI 25), one platoon from RI 8, plus a possible amphibious platoon together with artillery and helicopter support. Jones was not too perturbed by the conflicting intelligence reports and, incorrectly, tended to believe the SAS reports, on the assumption that they were actually "on the spot" and were able to provide more accurate information than the brigade intelligence staff.[30] Based on this intelligence and the orders from Thompson, Jones planned the operation to be conducted in six phases, as a complicated night-day, silent-noisy attack. C Company was to secure the start line, and then A Company was to launch the attack from the start line on the left (Darwin) side of the isthmus. B Company would launch their attack from the start line directly after A Company had initiated contact and would advance on the right (Boca House) side of the isthmus. Once A and B companies had secured their initial objectives, D Company would then advance from the start line between A and B companies and were to "go firm" on having exploited their objective. This would be followed by C Company, who were required to pass through D Company and neutralise any Argentine reserves. C Company would then advance again and clear the Goose Green airfield, after which the settlements of Darwin and Goose Green would be secured by A and D companies respectively.[31]

As most of the helicopter airlift capability had been lost with the sinking of SS Atlantic Conveyor, 2 Para were required to march the 13 miles (21 km) from San Carlos to the forming-up place at Camilla Creek House.[32] C Company and the commando engineers moved out from there at 22:00 on 27 May to clear the route to the start line for the other companies. A firebase (consisting of air and naval fire controllers, mortars, and snipers) was established by Support Company west of Camilla Creek, who were in position by 02:00 on the morning of 28 May.[33] The three guns from 8 Battery, their crew, and ammunition had been flown into Camilla Creek House by 20 Sea King helicopter sorties after last light on the evening of 27 May. The attack, to be initiated by A Company, was scheduled to start at 03:00, but because of delays in registering the support fire from HMS Arrow, only commenced at 03:35.[34]

Initial contact

On 4 May three Royal Navy Sea Harriers, operating from HMS Hermes, attacked the airfield and installations at Goose Green. During the operation, a Sea Harrier was shot down by Argentine 35 mm anti-aircraft fire; its pilot, RN Lieutenant Nick Taylor, was killed.[35]

As part of the diversionary raids to cover the British landings in the San Carlos area on 21 May, which involved naval shelling and air attacks, 'D' Squadron of the SAS, from their assembly point on Mount Usborne,[36] mounted a major raid to simulate a battalion-sized attack on Company A (under First Lieutenant Jorge Antonio Manresa), 12th Regiment, the company at the time being dug in on Darwin Ridge.[37]

On 22 May, four RAF Harriers, armed with cluster bombs, were launched from Hermes, their intended targets being the fuel dumps and Pucaras at Goose Green. The formation met intense anti-aircraft fire during their attack.[38] Captain Pablo Santiago Llanos of 601 Commando Company (escorting a shot down Royal Air Force Harrier pilot, Flight Lieutenant Jeffrey Glover, from Port Howard to Port Stanley) was present during the strike and observed:

I can assure you that it was the place I saw the best of people, especially my junior rank colleagues when it came to fighting spirit. Everyone in Goose Green would leave the houses, they would position themselves behind whatever cover there was, and would fire against the planes.[39]

On 26 May, Manresa's A Company, after a long march, was ready to mount a retaliatory raid on Mount Usborne, but on reaching the summit was surprised to find that the SAS had already vacated the feature.[40] The next day, Ernesto Orlando Peluffo, on Darwin Ridge, with his binoculars spotted British forward troops; and his RI 12 platoon repelled with long-range machine-gun fire a British reconnaissance patrol in the hours before the final attack.

Throughout 27 May, Royal Air Force Harriers were active over Goose Green. One of them, responding to a call for help from Captain Paul Farrar's C (Patrols) Company, was lost to 35 mm fire while attacking Darwin Ridge.[41][42][43] The Harrier attacks, the sighting of the forward British paratroopers, and the BBC announcing that the 2nd Battalion of the Parachute Regiment was poised and ready to assault Darwin and Goose Green the day before the assault alerted the Argentine garrison to the impending attack.[44]

Battle

Darwin Parks

At 03:35 HMS Arrow opened fire, firing a total of 22 star shells and 135 rounds of 4.5" high-explosive (HE) shells during a 90-minute bombardment, signalling the start of the attack.[45] In the ensuing night battle about twelve Argentines were killed.[16] Under heavy fire, the platoons of Sub-Lieutenants Marcelo Martin Bracco and Alejandro Garra withdrew after the initial clashes, reporting the loss of fifty percent of their men, killed, wounded, captured, or missing. The platoon under Sub-Lieutenant Gustavo Adolfo Malacalza fought a delaying action against the British paratroopers on Burntside Hill before taking up combat positions again on Darwin Ridge.[16]

The Coronation Ridge position temporarily halted Major Philip Neame's D Company. Two of his men, 24-year-old Lance-Corporal Gary Bingley and 19-year-old Private Barry Grayling, darted out from cover to charge the enemy machine gun nest and to protect advancing riflemen. Both were hit 10 metres (11 yd) from the machine gun, but shot two of the gun's crew before collapsing. Bingley was hit in the head and killed, while Grayling sustained a wound to the hip which he survived.[46] Bingley was posthumously awarded the Military Medal, and Grayling was decorated with the Queen's Gallantry Medal. With the enemy machine gun out of action, the paras were able to clear the Argentine platoon position, which was under Lieutenant Horacio Muñoz Cabrera, but at the cost of three Paras killed.[16]

2 Para continued its advance south via Darwin Parks. Around 7:30 am local time, the 1st Rifle Platoon from the 25th Regiment's C Company, under the command of 2nd Lieutenant Roberto Estévez, received orders to counterattack against 2 Para's B Company.[47] The Argentine platoon was able to block the British advance by taking up positions on Darwin Hill, from which, although wounded, Lieutenant Estévez started calling down fire support from Argentine 105 mm artillery and 120 mm mortars. He thus succeeded in holding up the advance of 2 Para's A Company, dispersing the attackers, as his men, caught out in the forward slopes as they prepared to renew their progress, sought cover in the nearby trenches. Estévez fell, mortally wounded by sniper fire. His dying order was to his radio operator Private Fabricio Edgar Carrascul, who continued to direct Argentine fire support. Bullets were riddling the Argentine position, and Carrascul was soon killed.[48] Both were posthumously decorated for this action: Estévez with the Argentine Nation to the Heroic Valour in Combat Cross (CHVC) and Private Carrascul with the Medal of Valour in Combat.[49] Private Guillermo Huircapán from Estévez's platoon describes the morning action:

Lieutenant Estévez went from one side to the other organizing the defense until all at once they got him in the shoulder. But with that and everything, badly wounded, he kept crawling along the trenches, giving orders, encouraging the soldiers, asking for everyone. A little later, they got him in the side, but just the same, from the trench, he continued directing the artillery fire by radio. There was a little pause, and then the English began the attack again, trying to advance, and again we beat them off.[50]

The first British assault was repulsed by fire from Sub-Lieutenant Ernesto Orlando Peluffo's RI 12 platoon, after the platoon sergeant, Buenaventura Jumilla, warned that the British were approaching. Major Farrar-Hockley spotted Argentine reinforcements on the hills before them. He shouted, "Ambush! Take cover!" just as the machine-guns opened fire.[51] The Royal Engineer officer attached to Farrar-Hockley's company, Lieutenant Clive Livingstone, wrote about the initial fight for Darwin Hill:

A massive volume of medium machine-gun fire was unleashed on us from a range of about 400 meters. The light now rapidly appearing enabled the enemy to identify targets and bring down very effective fire. Although this too would work for us, the weight of fire we could produce was not in proportion to the massive response it brought. We stopped firing – our main concern was to move away whenever pauses occurred in the attention being paid to us. The two platoons were not able to suppress the trenches, which were giving us so much trouble. We took about 45 minutes to extract ourselves through the use of smoke and pauses in the firing.[51]

The Paras were pinned down by heavy machine gun and automatic rifle fire. Between 9 and 10 that morning, 2 Para's A and B Companies broke off their attacks. They began to withdraw to the reverse side of Middle Hill and the base of Coronation Point.[52] "We were outraged. We just couldn't get across the open ground to get at their machine-guns, and after five hours of fighting, ammunition was critical," explained Major John Crosland in an interview with British war correspondent Max Hastings.[53] Corporal David Abols later said that an Argentine sniper who killed seven paras with shots to the head during the morning fighting was mainly responsible for holding up A Company.[lower-alpha 1] Nevertheless, the paras called on the Argentines to surrender.

At this juncture of the battle, A Company was in the gorse line at the bottom of Darwin Hill, and against the entrenched Argentines, who were looking down the hill at them. As it was now daylight, Lieutenant Colonel Jones led an unsuccessful charge up a small gully. Three of his men, his adjutant Captain Wood, A Company's second-in-command Captain Dent, and Corporal Hardman, were killed.[54] Shortly after that, Jones was seen to run west along the base of Darwin Ridge to a small re-entrant, followed by his bodyguard. He checked his Sterling submachine gun, then ran up the hill towards an Argentine trench. He was seen to be hit once, then fell, got up, and was hit again from the side. He fell meters short of the trench, shot in the back and the groin, and died within minutes.[54][lower-alpha 2] Jones was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

As Jones lay dying, his men radioed for urgent casualty evacuation. However, the British Scout helicopter sent to evacuate Jones was shot down by an Argentine FMA IA 58 Pucara ground-attack aircraft. The pilot, Lieutenant Richard Nunn RM was killed and posthumously received the DFC; and the aircrewman, Sergeant Bill Belcher RM was severely wounded in both legs.[54]

The death of Lieutenant-Colonel Jones was attributed to a sniper identified as an Argentine Army commando, Corporal Osvaldo Faustino Olmos, who was interviewed by the British newspaper Daily Express in 1996.[55] Olmos, of RI 25, had refused to leave his foxhole and his section fired at Jones and the five paratroopers who accompanied him as he moved forward.[lower-alpha 3] However, historian Hugh Bicheno attributed Jones' death to Corporal José Luis Ríos of the 12th Regiment's Reconnaissance Platoon.[56] Ríos was later fatally wounded manning a machine-gun in his trench by Abols, who fired a 66 mm rocket.

With the death of Jones, command passed to Major Chris Keeble. Following the failure of this initial attack and the death of Jones, it took Keeble two hours to reorganize and resume the attack.[52]

Darwin Hill

By the time of Jones' death, it was 10:30, and Major Dair Farrar-Hockley's A Company made a third attempt to advance, but this petered out. Eventually, the British company, hampered by the morning fog as they advanced up the slope of Darwin Ridge, were driven back to the gully by the fire of the survivors of the 1st Platoon from RI 25's C Company. During the morning fighting, 2 Para's mortar crews fired 1,000 rounds to keep the enemy at bay, and prevented the Argentines' fire being properly aimed. Many of the Argentine fatalities during the fighting were caused by mortar fire.[lower-alpha 4][57]

Expecting a low-level strike from Argentine Air Force Skyhawk fighter-bombers to materialise in support of the Darwin Ridge defenders, Company Sergeant-Major Juan Coelho spread out white bedsheets in front of the trenches to help guide in the pilots and was severely wounded in the process. The Argentine flight of five Skyhawks instead encountered the British hospital ship Uganda, losing valuable time reporting the incident and returning to investigate the boat further before continuing with their mission. The Skyhawk pilots, having lost much fuel and flying in bad weather, carried out a poorly executed bomb run, firing on Argentine positions as they released their bombs and being engaged by Argentine anti-aircraft fire that damaged the lead plane.[58][59]

It was almost noon before the British advance resumed. A Company soon cleared the eastern end of the Argentine position and opened the way forward. There had been two battles for the Darwin hillocks—one around Darwin Hill (Black strong point) looking down on Darwin Bay, and an equally fierce one in front of Boca Hill (White strong point), also known as Boca House Ruins. Sub-Lieutenant Guillermo Ricardo Aliaga's 3rd Platoon of RI 8's C Company held Boca Hill. The position of Boca Hill was reported taken at 13.47 local time,[60] after heavy fighting by Major John Crosland's B Company, with support from the MILAN anti-tank platoon. Sub-lieutenants Aliaga and Peluffo were gravely wounded in the battle. Crosland was the most experienced British officer; and, as the events of the day unfolded, it was later said that Crosland's cool and calm leadership turned the Boca House section of the front line.

About the time of the final attack on the Boca House position, A Company overcame the Argentine defenders on Darwin Hill, finally reporting taking the Black strong point at 13:13 local time,[61] with the defenders having resisted for nearly six hours,[lower-alpha 5][62] with many Argentine and British casualties. Majors Farrar-Hockley and Crosland each won the Military Cross for their efforts. Corporal David Abols was awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal for his daring charges, which turned the Darwin Hill battle.

An FMA Pucara, returning from the battle, crashed about 10:00 AM in high ground between Goose Green and Stanley. Its pilot, Lieutenant Gimenez, was killed. The cause is not known, either from battle damage or flight accident. It was the 58th Argentine aircraft lost in the war.

Attack on the airfield

After the victory on Darwin Ridge, C and D Companies began to make their way to the small airfield, as well as to Darwin School, which was east of the airfield, while B Company made their way south of Goose Green Settlement. A Company remained on Darwin Hill. C Company took heavy losses when they became the target of intense direct fire from 35 mm anti-aircraft guns that caused 20 percent casualties.[63] Private Mark Holman-Smith, a signaler in the company headquarters, was killed by the anti-aircraft guns while trying to recover a heavy machine gun from wounded Private Steve Russell.[64]

Argentine Air Force anti-aircraft gunners under Lieutenant Darío Del Valle Valazza, and the RI 12 platoon under Sub-Lieutenant Carlos Oslvaldo Aldao, attempted to halt the renewed advance that commenced at 2:25 pm from Boca Hill,[65] but were forced to abandon their positions, including the five remaining 20 mm Rheinmetall guns at Cóndor airfield, reporting the loss of two arms and an Elta radar to MILAN missiles or mortar fire, with three defenders from Grupo 1 de Artillería Antiaérea de la Fuerza Aérea Argentina (G1AA) killed (Privates Mario Ramón Luna, Luis Guillermo Sevilla and Héctor Walter Aguirre from G1AA[66] and Privates Roque Evaristo Sánchez and Avelino Néstor Oscar Pegoraro from Aldao's platoon) and several wounded, including Lieutenant Valazza. A large part of the RI 12 platoon was overrun and forced to surrender, but Aldao, along with a corporal, managed to escape[65][67] in the confusion of the Argentine airstrikes that materialised later that afternoon.

Lieutenant James Barry's No. 12 Platoon, D Company, saw some violent action at the airfield. They were ambushed by Sub-Lieutenant Juan José Gómez-Centurión's 2nd Romeo Rifle Platoon of the 25th Regiment's Company C.[16] Still, Private Geordie Knight shot dead two of the attackers (Privates José Luis Allende and Ricardo Andrés Austin) that had crawled forward,[68] and then reported the events to Major Neame.[lower-alpha 6] Private Graham Carter from No. 12 Platoon describes the airfield action:

In the first volley of shots, Mr. Barry was hit quite badly and got tangled in the barbed wire fence. They then used him as target practice. In the same instance, [Corporal] Paul Sullivan got hit directly behind me in the knee, and then he got hit several more times in the head. I was really lucky, as with two others I was protected by a small scoop in the ground. The other gunner, Brummy [Private Brummie Mountford], got hit directly after the first volley of shots, ricochets off the GPMG, which hit him in the shoulder and the back, so he was in quite a bad way. Smudge [Lance-Corporal Nigel Smith], our section 2ic, fired a 66 mm into the trenches that were giving us trouble, but it must have been damaged in some way as the whole thing went off and damaged him badly in the face and chest. As he was only a few feet away, I went across to administer first aid to him, but as I moved, I got a bullet in my helmet, which took a chunk of it away. There was no way I was going to try going across there again.[69]

Private John Graham, from Lieutenant Chris Waddington's No. 11 Platoon, claimed that Lieutenant Barry and Corporal Sullivan, during a local truce, went forward to accept the Argentine surrender and that the defenders suddenly opened fire without warning, killing Barry and wounding Sullivan, with one Argentine crawling forward to Sullivan and shooting him at point-blank range:

I saw the white flag incident; I was in 11 Platoon. We were going up the hill, and the flag went up. The officer [Barry] called the sergeant [sic] and then got halfway up the hill. Bang! They let rip into them, Killed them. One guy [Corporal Paul Sullivan] was hit in the knee, and one of the bastards came forward and shot him in the head. He moved forward out of his position and shot him.[70]

Private Carter won the Military Medal by rallying the survivors in No. 12 Platoon and leading them forward at bayonet point to take the airfield.[16][lower-alpha 7] The platoon sergeant had earlier charged the enemy's Romeo platoon with his belt-fed machine-gun, killing four of them.

According to Sub-Lieutenant Gómez-Centurión:

I set out with thirty-six men toward the north. Passing the school, we entered a depression from which we saw the hill. I sent a scouting party ahead, and they told me that the British were advancing from the other side of the low ridge, some one hundred and fifty men. [My] men were very tense; there was a brutal cold; we shivered with cold, with fear. When they were about fifty meters away, we opened fire. We kept firing for at least forty minutes. They started to attack our flank, my soldiers had to take cover, the firing went down, and the situation started to become critical. Then we were surrounded, we had wounded, people started to lose control. I began to ask about casualties, each time, more casualties. There was no way out behind because we had been flanked, nearly surrounded. So when there was a pause in the firing, I decided that it was the time to stop, and I gave the order to disengage.[50]

The RI 25 platoon defending the airfield fell back into the Darwin-Goose Green track and was able to escape. Sergeant Sergio Ismael Garcia of RI 25 single-handedly covered the withdrawal of his platoon during the British counterattack. He was posthumously awarded the Argentine Nation to the Valour in Combat Medal. Under orders from Major Carlos Alberto Frontera (second in command of RI 12), Sub-Lieutenant César Álvarez Berro's RI 12 platoon took up new positions and helped cover the retreat of Gómez-Centurión's platoon along the Darwin-Goose Green track.[67]

Four Paras of D Company and approximately a dozen Argentines were killed in these engagements. Among the British dead were 29-year-old Lieutenant Barry and two NCOs, Lance-Corporal Smith and Corporal Sullivan, who were killed after Barry's attempt to convince Sub-Lieutenant Gómez-Centurión to surrender was rebuffed.[16][lower-alpha 8][71][72] C Company did not lose a single man in the Darwin School fighting, but Private Steve Dixon, from D Company, died when a splinter from a 35 mm anti-aircraft shell struck him in the chest.[73] The Argentine 35 mm anti-aircraft guns under the command of Sub-Lieutenant Claudio Oscar Braghini reduced the schoolhouse to rubble after sergeants Mario Abel Tarditti and Roberto Amado Fernandez reported to him that sniper fire was coming from there.[74][75]

At around this time, three British Harriers attacked the Argentine 35 mm gun positions; the army radar-guided guns were unable to respond effectively because a piece of mortar shrapnel had earlier struck the generator to the firearms and fire-control radar. This attack considerably lifted morale among the British paras. Although it was not known at the time, the Harriers came close to being shot down in their bomb run after being misidentified as enemy aircraft by Lieutenant-Commander Nigel Ward and Flight Lieutenant Ian Mortimer of 801 Squadron.[lower-alpha 9] According to Lieutenant Braghini's report,[76] and at least one British account,[77] the Harrier strike missed their intended target; but the Argentine antiaircraft guns were already out of action anyway.

Meanwhile, the RI 12 platoon—under Sub-Lieutenant Orlando Lucero, a platoon that Lieutenant-Colonel Piaggi and Major Frontera had organised, using survivors from the earlier fighting—took up positions on Goose Green's outskirts and continued to resist, while supporting air force Pucara and navy Aermacchi aircraft struck the forward British companies. The Argentine pilots did not have much effect, suffering two losses: at 5:00, when a Macchi 339A (CANA 1 squadron) was shot down by a Blowpipe missile from the Royal Marines' air defense troop, killing Sub-Lieutenant Daniel Miguel.

Just about 10 minutes later, another Pucara was shot down by small arms fire from 2 Para, drenching several paratroopers with fuel and napalm, which fortunately did not ignite.[78] Lieutenant Miguel Cruzado survived and was captured by British forces on the ground.

Situation at last light on 28 May

By last light, the situation for 2 Para was critical. A Company was still on Darwin Hill, north of the gorse hedge; B Company had penetrated much further south and had swung in a wide arc from the western shore of the isthmus eastwards towards Goose Green. They were isolated and under fire from an Argentinian platoon and unable to receive mutual support from the other companies.[79] To worsen their predicament, Argentine helicopters—a Puma, a Chinook and six Hueys—landed southwest of their position, just after last light, bringing in the remaining Company B of RI 12 (Combat Team Solari) from Mount Kent.[80]

B Company managed to bring in artillery fire on these new enemy reinforcements, forcing them to disperse towards the Goose Green settlement, while some re-embarked and left with the departing helicopters.[81] For C Company, the attack had also fizzled out after the battle at the school-house, with the company commander injured, the second-in-command unaccounted for, no radio contact, and the platoons scattered with up to 1,200 meters between them.[82] D Company had regrouped just before last light, and they were deployed to the west of the dairy—exhausted, hungry, low on ammunition, and without water.[83] Food was redistributed, for A and C Companies to share one ration-pack between two men; but B and D Companies could not be reached. At this time, a British helicopter casualty evacuation flight took place, successfully extracting C Company casualties from the forward slope of Darwin Hill, while under fire from Argentine positions.[84]

To Keeble, the situation looked precarious: the settlements had been surrounded but not captured, and his companies were exhausted, cold, and low on water, food, and ammunition. His concern was that the Argentine Company B's reinforcements, dropped by helicopter, would either be used in an early morning counter-attack or used to stiffen the defenses around Goose Green. He had seen the C Company assault stopped in its tracks by the anti-aircraft fire from Goose Green, and had seen the Harrier strikes of earlier that afternoon missing their intended targets. In an order group with the A and C Company commanders, he indicated his preference for calling for an Argentine surrender, rather than facing an ongoing battle the following morning. His alternative plan, if the Argentines did not surrender, was to "flatten Goose Green" with all available fire-power and then launch an assault with all forces possible, including reinforcements he had requested from Thompson. On Thompson's orders, J Company of 42 Commando, Royal Marines, the remaining guns of 8 Battery, and additional mortars were helicoptered in to provide the necessary support.[85]

Surrender

Once Thompson and 3 Brigade had agreed to the approach, a message was relayed by CB radio from San Carlos to Mr. Eric Goss, the farm manager in Goose Green—who, in turn, delivered it to Piaggi. The call explained the details of a planned delegation who would go forward from the British lines, bearing a message, to the Argentine positions in Goose Green. Piaggi agreed to receive the delegation.[86] Soon after midnight, two Argentine Air Force warrant-officer prisoners of war (PW) were sent to meet with Piaggi and to hand over the proposed terms of surrender:

- That you unconditionally surrender your force to us by leaving the township, forming up aggressively, removing your helmets, and laying down your weapons. You will give prior notice of this intention by returning the PW under a white flag with him briefed as to the formalities by no later than 0830 hrs local time.

- You refuse in the first case to surrender and take the inevitable consequences. You will give prior notice of this intention by returning the PW without his flag (although his neutrality will be respected) no later than 0830 hrs local time.

- In the event and by the terms and conditions of the Geneva Convention and Laws of War, you will be held responsible for the fate of any civilians in Darwin and Goose Green, and we by these terms do give notice of our intention to bombard Darwin and Goose Green.

On receiving the terms, Piaggi concluded:

The battle had turned into a sniping contest. They could sit well out of range of our soldiers' fire and, if they wanted to, raze the settlement. I knew that there was no longer any chance of reinforcements from the 6th Regiment's B Company (Compañía B 'Piribebuy'). So I suggested to Wing Commander [Vice Commodore] Wilson Pedrozo that he talk to the British. He agreed reluctantly.[87]

Taking advantage of the local ceasefire, Second Lieutenant Juan Gómez Centurión—at the head of two air force stretcher-bearers, Privates David Alejandro Díaz and Reynaldo Dardo Romacho and an accompanying air force medical officer, Lieutenant Carlos Beranek—found and rescued Corporal Juan Fernández who had been severely wounded and left behind British lines.[88] The next morning, agreement for an unconditional surrender was reached. Pedrozo held a short parade, and those on show then laid down their weapons. After burning the regimental flag, Piaggi led the troops and officers, carrying their personal belongings, into captivity.[89]

Aftermath

Prisoners and casualties

Between 45[90][91] and 55 Argentines were killed[92] (32 from RI 12, 13 from Company C RI 25, five killed in the platoon from RI R8, 4 Air Force staff, and one Navy service member),[93] and about 86 wounded.[92]

The claim in various British books that the 8th Regiment lost five killed defending Boca House is disputed, with other sources claiming that Corporal Juan Waudrik (supposedly died at Boca House) was mortally wounded in late May after the tractor he was riding detonated a mine at Fox Bay,[94] and that Privates Simón Oscar Antieco, Jorge Daniel Ludueña, Sergio Fabián Nosikoski, and Eduardo Sosa—the four conscripts reportedly killed fighting alongside Waudrik—were killed in the same locality on West Falkland during a naval bombardment on 9 May. In all, RI 8 lost 5 killed during the Falklands War.

The remainder of the Argentine force was taken prisoner. Argentine dead were buried in a cemetery to the north of Darwin, and 140[95][96] wounded were evacuated to hospital ships via the medical post in San Carlos. Prisoners were used to clear the battlefield; in an incident involving the moving of artillery ammunition, the RI 12 C Company platoon under Sub-Lieutenant Leonardo Durán, was engulfed in a massive explosion that left 5 dead or missing and 10 seriously wounded.[2][97] After clearing the area—with military chaplain Mora and sub-lieutenants Bracco and Gómez-Centurión assisting with the burying of the dead—the prisoners were marched to, and interned in, San Carlos.[98] The British lost 18 killed (16 Paras, one Royal Marine pilot, and one commando sapper)[2] and 64 wounded. The seriously injured were evacuated to the hospital ship SS Uganda.[99]

By 3 June, the Gurkhas were deployed at Darwin and Goose Green. They were used in helicopter-borne operations to find Argentine patrols operating on the southern flank of the British advance to Port Stanley. This resulted in an encounter with a 10-man army–air force patrol under Lieutenant Jaime Enrique Ugarte from the Argentine Air Force's 1st Anti-Aircraft Group and Sergeant Roberto Daniel Berdugo from the 12th Regiment that had been helicoptered to Egg Harbour House, an abandoned farmhouse in Lafonia to shoot down British aircraft with SA-7 shoulder-launched missiles. On 7 June, a Sea King arrived with 20 Gurkhas to clear this Goose Green outpost. On being ordered to lie down to be searched by the Gurkhas, all the wet and hungry Argentine soldiers, including Sergeant Berdugo, did so, except the air force officer. A Gurkha rifleman, brandishing a 10" Kukri blade, threatened the air force officer with beheading, and Lieutenant Ugarte obeyed.

Commanders

Lieutenant-Colonel Ítalo Ángel Piaggi surrendered his forces in Goose Green on the Argentinian National Army Day (29 May). After the war, he was forced to resign from the army, and faced ongoing trials questioning his competence at Goose Green. In 1986, he wrote a book titled Ganso Verde, in which he strongly defended his decisions during the war and criticised the lack of logistical support from Stanley. In his book, he said that Task Force Mercedes had plenty of 7.62 mm rifle ammunition left, but had run out of 81 mm mortar rounds; and there were only 394 shells left for the 105 mm artillery guns.[100] On 24 February 1992, after a long fight in both civil and military courts, Piaggi had his retired military rank and pay reinstated, as a full colonel.[101] He died in July 2012.[102]

Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert 'H' Jones was buried at Ajax Bay on 30 May; after the war, his body was exhumed and transferred to the British cemetery in San Carlos.[103] He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.[104]

Major Chris Keeble, who took over command of 2 Para when Jones was killed, was awarded the DSO for his actions at Goose Green.[105] Keeble's leadership was one of the key factors that led to the British victory, in that his flexible style of command and the autonomy he afforded to his company commanders were much more successful than the rigid control, and adherence to plan, exercised by Jones.[106] Despite sentiment among the soldiers of 2 Para for him to remain in command, he was superseded by Lieutenant-Colonel David Robert Chaundler, who was flown in from the UK to take command of the battalion.[107]

BBC incident

During the planning of the assault of both Darwin and Goose Green, the battalion headquarters were listening in to the BBC World Service, when the newsreader announced that the 2nd Battalion of the Parachute Regiment was poised and ready to assault Darwin and Goose Green. This caused great trepidation among the commanding officers of the battalion, with fears that the operation was compromised. Jones became furious with the level of incompetence and told BBC representative Robert Fox he was going to sue the BBC, Whitehall, and the War Cabinet.[108]

Field punishments

In the years after the battle, Argentine army officers and NCOs were accused of handing out brutal field punishment to their troops at Goose Green, and other locations, during the war.[109] In 2009, Argentine authorities in Comodoro Rivadavia ratified a decision made by authorities in Río Grande, Tierra del Fuego, announcing their intention to charge 70 officers and NCOs with inhumane treatment of conscript soldiers during the war.[110]

There was, however, false testimony that was used as evidence in accusing the Argentine officers and NCOs of abandonment; and Pablo Vassel, who had denounced the alleged perpetrators, had to step down from his post as head of the human rights sub-secretariat of Corrientes Province.[111] Other veterans were skeptical about the veracity of the accusations, with Colonel José Martiniano Duarte, an ex–601 Commando Company officer and decorated veteran of the Falklands War, saying that it had become "fashionable" for ex-conscripts to accuse their superiors of abandonment.[112] Since the 2009 announcement was made, no one in the military, or among the retired officers and NCOs, has been charged, causing Vassel to comment in April 2014:

For over two years we've been waiting for a final say on behalf of the courts ... There are some types of crimes that no state should allow to go unpunished, no matter how much time has passed, such as the crimes of the dictatorship. Last year Germany sentenced a 98-year-old corporal for his role in the concentration camps in one of the Eastern European countries occupied by Nazi Germany. It didn't take into account his age or rank."[113]

References

Notes

- "This sniper fire was responsible for the deaths of at least seven paratroopers, according to Abols – 'all headshots. That is the main reason A Company was stuck'. He says the sniper was firing from about 500 meters behind the Darwin Hill position." (Not Mentioned in Despatches: The History and Mythology of the Battle of Goose Green (James Clarke & Co., 2006.) p. 79.)

- According to Dan Snow and Peter Snow, "The Argentine corporal in that trench, Osvaldo Olmos, remembers seeing Jones charge past him alone, leaving his followers in the gully below. Olmos said he was astonished at Jones's reckless bravery: his shots, fired from behind, may have been the ones that brought Jones down." (20th Century Battlefields (Random House, 2012) p. 282.)

- "Without telling anyone or looking back, he ran up the gully that Corporal Adams had attacked when A Company was first fired upon, past the seriously wounded Private Tuffen. Sergeant Barry Norman, his close escort, was the first to move, followed by Lance Corporal Beresford, who was part of his escort and had been Jones's driver, Major Rice, and two signallers. Jones advanced up a small re-entrant toward a trench, which Corporal Osvaldo Olmos, from Estevez's platoon, later claimed was held by his group." Van Der Bijl, Victory in the Falklands, pp. 108–109

- "Nevertheless, the section's two mortar crews had fired over 1,000 bombs in the two hours of the A Company action, the mortars themselves sinking further and further into the soft peat until eventually, only their muzzles were visible." Harclerode, p. 329.

- "After nearly six hours, the battle for Darwin Hill was over, but not without grievous loss: the commanding officer, the Adjutant, A Company Second-in-Command and nine non-commissioned officers and soldiers were killed and several wounded." No Picnic: 3 Commando Brigade in the South Atlantic, 1982, Julian Thompson, pp. 79–80, Casemate Publishers, 1992

- According to historian Mark Adkin, both Lance-Corporal Nigel Smith and Corporal Paul Sullivan were killed fighting: "Lance Corporal Smith aimed his 66mm rocket, but as he did so he was shot at the moment of firing. The rocket exploded in a flash of flame on his back; he died instantly. In the general confusion, Corporal Sullivan was also hit and killed." Mark Adkin, p. 326, Goose Green: A Battle Is Fought to Be Won, Leo Cooper 1992

- "He [Private Graham Carter] had been involved in a savage ambush which, as the Paras regained their initiative and fought back, turned into a vicious gun battle. His platoon commander had been killed, and his section effectively put out of action, with section commander killed and 2 ic [second in command] seriously wounded. Despite being the most inexperienced man in the platoon, Private Carter had fought off the enemy, attended to the wounded, then got control of the section and called up the rest of the platoon to make a counterattack – all under continuous fire." The Scars of War, Hugh McManners, p. 126, HarperCollins, 1993

- "The newspapers inevitably made much of this scrap; however, both sides agreed that this was a tragic misunderstanding. The Argentines later claimed that when Barry offered second Lieutenant Centurion terms, he replied, 'Son of a bitch! You have got two minutes to return to your lines before I open fire. Get out! '" Van Der Bijl, Victory in the Falklands, p. 113

- ."I had convinced myself that the three were enemy aircraft. But I also knew that Morts, more than anybody, should be able to recognise a GR 3 even from this height and range. I called the control ship, HMS Minerva. 'Do you have any friendlies in the area at a low level?' If there were any, Minerva would know about it. 'Negative. No friendlies in the Sound.' Just at that moment of distraction, I lost sight of the three swept-wing shapes below. They disappeared into the multi-colored background of the water. 'I've lost the fucking things, Morts. do you hold them?' 'Negative. But I'm sure they were GR 3s.' I was mad as a hatter and wasn't thinking straight. I was tired, and 'missing' the enemy jets seemed to drain me of all energy. If I hadn't been so tired, I might have considered the line 'better safe than sorry,' but I was in no mood for that when I landed on board. The debrief was short and to the point: 'GR 3s, my arse! '" Sea Harrier Over the Falklands, Nigel Ward, p. 227, Pen and Sword, 1993

Footnotes

- Adkin, Mark (2003). Goose Green – A battle is Fought to be Won. London: Cassell. p. 23. ISBN 0304354961.

- Van Der Bijl (1999) p. 140

- Dale, Iain (2002). Memories of the Falklands. London: Politico. p. 73. ISBN 9781842750186.

- "The Argentines lost 45 men killed, 90 wounded and 961 captured." The Falklands 1982: Ground Operations in the South Atlantic, Gregory Fremont-Barnes, p. 43, Osprey Publishing, 2012

- "El total de heridos fue 98 (4 oficiales, 22 suboficiales y 72 soldados)." Malvinas: otras historias, Rubén Oscar Palazzi, p. 202, Claridad, 2006

- "A total of 961 prisoners were accounted for including 81 held at Camilla Creek House." The Official History of the Falklands Campaign: War and Diplomacy, Volume 2, Lawrence Freedman, p. 493, Psychology Press, 2005

- "Falkland Islands – Stanley's Sunrise and Sunset on 27 May 1982". TimeZoneGuide. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- Leone, Vincent R. Major USMC. "The Falkland Islands War: Winning With Infantry". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- Fitz-Gibbon (2002) p. 5

- Moore, Darren Maj. "Rear Admiral Woodward: Political Influences during the Falklands War" (PDF). Australian Defence Force Journal: Issue 165, 2004. Australian Defence Force.

- Middlebrook, Martin (1985). Operation Corporate: The Falklands War, 1982 (1st ed.). London: Viking: Penguin Books Ltd. p. 249. ISBN 0670802239.

- Thompson, Julian (2008). No Picnic: 3 Commando Brigade in the Falklands. Pen and Sword Military. p. 200. ISBN 978-1844158799.

- Hastings, Max; Jenkins, Simon (1983). The Battle for the Falklands. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 264–265. ISBN 9780393017618.

- Freedman, Lawrence Sir (2005). The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, Volume 2: War and Diplomacy. Oxford: Routledge. p. 477. ISBN 978-0714652078.

- van der Bijl, Nicholas (1999). Nine Battles to Stanley. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. p. 116. ISBN 9780850526196.

- Blood and Mud at Goose Green Archived 4 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine. David Aldea & Don Darnell, EBSCO Host Connection.

- Andrada, pp. 86–90

- Fitz-Gibbon (2002) pp. 4–5

- Van der Bijl (1999) p. 117

- The men of Co. C/RI 25 fought with courage, perseverance, and effectiveness at San Carlos and Goose Green, having received a good deal of special forces training under the energetic command of LtCol. Seineldín. The Military Sniper Since 1914, Martin Pegler, p. 63, Osprey Publishing, 2001

- Boyce (2005) p. 129

- Argentine Fight for the Falklands, Martin Middlebrook, p.64, Pen & Sword, 2003

- Nine battles to Stanley, Nicholas Van der Bijl, p.13, Leo Cooper, 30 September 1999

- Guerra de Malvinas Regimiento de Infanteria 12

- Fitz-Gibbon (2002) p. 6

- Partes de Guerra, Graciela Speranza, Fernando Cittadinil, p. ?, Numa Ediciones, 2000

- Middlebrook (1985) p. 252

- , Freedman (2005) p. 481

- Fitz-Gibbon (2002) p. 8

- Boyce, D. George (2005). The Falklands War (1st ed.). Hampshire: Macmillan. p. 128. ISBN 9780333753958.

- Fitz-Gibbon (2002) Appendix 2, pp190-194

- Middlebrook (1985) p. 254

- Fitz-Gibbon (2002) p. 23

- Fitz-Gibbon (2002) p. 25

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- We were landed to the East of Mount Usborne carrying huge weights of ammunition just after dark on the night of 20/21 May. Memories of the Falklands, Iain Dale, p. 36 Politico's, 2002

- Rodríguez Mottino, Héctor (1984). La Artillería Argentina en Malvinas. Ed. Clío, pp. 193–194. ISBN 950-9377-02-3. (in Spanish)

- ."On the late evening of 22, May four Harriers were launched from Hermes armed with CBUs, their intended targets being the POL dumps and Pucaras at Goose Green. The aircraft were subject to intensive anti-aircraft fire during this attack." RAF Strike Command, 1968–2007, Kev Darling, p. 159, Casemate Publishers, 2012

- Comandos en Acción, Isidoro Jorge Ruiz Moreno, Emecé Editores, 1986

- ."1830 hs – Se Lanza el Ataque de desarticulación Sobre el punto acotado 392 para perturber, hostigar y desconcentrar al enemigo; es una intención, por cuanto no tengo información fehaciente Sobre Su Presencia y actividad." Ganso Verde, Italo Angel Piaggi, p. 64, Sudamericana/Planeta, 1986

- Pook, Jerry (2007). RAF Harrier Ground Attack-Falklands. Pen & Sword Books, ltd., p. 109. ISBN 978-1-84415-551-4 (in English)

- Jackson, Robert (1985). The RAF in action: from Flanders to the Falklands. Blandford Press, p. 156. ISBN 0713714190

- Van der Bijl, Nicholas (1999). Nine battles to Stanley. Leo Cooper, p. 127. ISBN 0850526191

- Middlebrook (1985) p. 257

- Roberts, John (2009). Safeguarding the Nation: The Story of the Modern Royal Navy. Seaforth Publishing. p. 161. ISBN 978-1591148128.

- At home on the new battlefront. An ex-British soldier is putting Pasco High on the state soccer map. By Izzy Gould. Tampa Bay Times. Published 9 February 2007

- ."It was still dark when Estevez moved north past the dairy, up the reverse slope of Darwin Hill, over the gorseline to join Pelufo's platoon on the ridge west of the settlement. The two officers conferred. Estevez explained that his orders were to counter-attack, to advance north to assist Manresa's A Company." The Battle of Goose Green, Mark Adkin, p. 146, Pen & Sword, 2017

- ."He was hit in the leg, arm and left eye, while crouched with his radio operator, Private Carrascul, trying to adjust supporting artillery fire. Carrascul continued to fight the battle over the radio himself until he, too, was killed. It is an interesting example of the closeness that often develops, despite the differences in rank, between an officer and his operator. The officer relies heavily on the competence of his radio operator. " The Battle of Goose Green, Mark Adkin, p. 193, Pen & Sword, 2017

- Decreto Nacional 577/83 - Condecoraciones al personal que ha intervenido en el conflicto armado con el Reino Unido por la recuperación de las Islas Malvinas, Georgias del Sur y Sandwich del Sur

- Reassessing the Fighting Performance of Conscript Soldiers

- The Battle for the Falklands, Max Hastings, Simon Jenkins, p. 243, Joseph, 1983

- ."These British reverses occurred between 9.00 a.m. and 10.00 a.m. It took two hours for 2 Para's second-in-command to reorganize the attack." The Falklands War, D. George Boyce, p. 131, Macmillan International Higher Education, 2005

- The Battle for the Falklands, Max Hastings, Simon Jenkins, p. 244, Michael Joseph, 1983

- "Lieutenant Richard J. Nunn, DFC". SAMA(82): Garden of Remembrance. 1996–2009. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "La Muerte de un coronel británico en Malvinas. Clarín. 18 June 1996". Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Lost in the fog of war. Robert Fox takes issue with Hugh Bicheno's history of the Falklands conflict, Razor's Edge. By Robert Fox. The Guardian Published Saturday 1 April 2006

- "Some of [the Argentine dead] seemed to be looking at us, their dead eyes full of reproach. Few looked peaceful. Some had died trying to escape back into the foxholes they'd poured from. Many had fallen to the pinpoint shower of mortar shells that had dropped on them." Spearhead Assault, John Geddes, p. 12, Random House, 2008

- ."They passed up the marked hospital ship Uganda and executed a turn into Darwin. Unknowingly, they made a pass over their positions, firing as they went, and were promptly repelled by their air defenses. The first plane was hit but could still fly." History of the South Atlantic Conflict, Rubén Oscar Moro, p. 244, Praager, 1990

- "1130/1150 hs – Ataque aéreo enemigo a las posiciones (Compañía A y Batería de Artillería) Desde tres direcciones, y en cuatro Oportunidades, con Bombas, ametralladoras y granadas beluga. Nuestro Fuego derriba un avión ( a confirmar )." Ganso Verde, Ítalo Ángel Piaggi, p. 94, Sudamericana/Planeta, 1986

- "1647 Support Company had reported lots of white flags." Not Mentioned in Despatches: The History and Mythology of the Battle of Goose Green, Spencer Fitz-Gibbon, p. 197, James Clarke & Co., 2006

- "1613 Enemy have surrendered on BLACK. Now moving to WHITE." Not Mentioned in Despatches: The History and Mythology of the Battle of Goose Green, Spencer Fitz-Gibbon, p. 197, James Clarke & Co., 2006

- "It had taken around six hours to dislodge the Argentinians from their vital ground - which says much for their tenacity." H. Jones VC: The Life and Death of an Unusual Hero, John Wilsey, Hutchinson, 2002

- Fitz-Gibbon, (2002), pp. 147–148.

- Reynolds, David (2002). Taskforce: the illustrated history of the Falklands War. Sutton, p. 150. ISBN 0-7509-2845-X

- DEFENSA Y CAÍDA DE DARWIN-PRADERA DEL GANSO, página 12

- BASE AÉREA MILITAR CÓNDOR

- Malvinas Banda de Hermanos Regimiento de Infantería 12 (Programa 19 - Martes 19 de Julio 2016)

- "As Godfrey made his dash for the rut, Knight shot and killed two of the enemy who was skirmishing forward, and Private Carter fired coolly and continuously into the nearest trench." The Battle of Goose Green, Mark Adkin, p. 236, Pen & Sword, 2017

- Forgotten Voices of the Falklands, Hugh McManners, p. 265, Random House, 2008

- The World's Elite Forces, Bruce Quarrie, p. 18, Berkley Books, 1988

- The fight for the "Malvinas": The Argentine forces in the Falklands War. Martin Middlebrook. p. 189. Penguin, 1990

- The History of the South Atlantic conflict: The War for the Malvinas. Rubén Oscar Moro. p. 264. Praeger, 1989

- "Goose Green: The Argentinian Story" Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine by David Aldea. British Small Wars website

- "Observé por el visor y confirmé la Presencia de Los ingleses. Apunté a la base de la estructura de dos pisos y abrí el Fuego. Pedazos completos de Ella desaparecieron al Hacer Impacto Los proyectiles y se incendió luego." Malvinas: Relatos de Soldados, Martin Antonio Balza, p. 149, Circulo Militar, 1983

- La artillería antiaérea terminó Haciendo Fuego de superficie

- "No habíamos terminado de tomar cubierta cuando un Harrier se desprende de entre Los Cerros y suelta una bomba "beluga" Sobre el cañón; pero con tan mala puntería que la mitad del ramillete cae en el agua y el resto a unos 80 metros de la pieza". Braghini's statement, Rodríguez Mottino, p. 196

- "Two misses and the cluster bombs the Harriers had been carrying killed fish as they exploded in the sea just off the settlement." Excerpt from Geddes, John (2008) Spearhead Assault: Blood, Guts, and Glory on the Falklands Frontlines. Arrow, p. 193. ISBN 1846052475

- ."One aircraft crashed close by, drenching several men with fuel and napalm, which happily did not ignite." "No Picnic", Julian Thompson, Pen & Sword, 2008

- Adkin (2003), p. 339

- Adkin (2003), p. 340

- Adkin (2003), p. 341

- Adkin (2003), p. 343

- Adkin (2003), p. 345

- Adkin (2003), p. 346

- Adkin (2003), p. 351

- Adkin (2003), pp. 353–354

- The Falklands War, D. George Boyce, p. 131, Macmillan International Higher Education, 2005

- El arriesgado Rescate de un suboficial herido que quedó detrás de las líneas enemigas

- Van Der Bijl (1999) pp. 139

- "Their fatalities total 45 men ..." Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the Western Hemisphere, 1492 to the Present, Volume 2, David Marley, p. 1073, ABC-CLIO, 2008

- "The Argentines lost 45 men killed, 90 wounded and 961 captured." The Falklands 1982: Ground Operations in the South Atlantic, Gregory Fremont-Barnes, p. 43, Osprey Publishing, 2012

- Boyce (2005), p. 131

- Adkin (2003), p. 363

- "Pero la Lluvia y el Barro hizo que el tractor se desplazara Fuera de la senda e hiciera estallar una mina que le voló una pierna y dos días después, le produjo la Muerte." Malvinas: 20 Años, 20 Héroes, Armando Fernandez, p. 107, Fundación Soldados, 2002

- "We had previously arranged for a message to be sent to Argentina requesting the Bahia Paraiso to rendezvous with our hospital ship SS Uganda in an area which we have set aside for Hospital Ships some 30 miles north of Falklands Sound. 140 wounded Argentine servicemen – who are receiving medical attention on board the UGANDA – will be transferred to the Argentine ship for an early return home." The Falklands War: The Official History, p.44, Latin American Newsletters, 1983

- "Towards the end of May Uganda entered Falkland sound to evacuate casualties, and some days later met the Argentine Bahia Paraiso, 30 miles north of Falkland Sound were 140 casualties were transferred." Jane's Merchant Shipping Review, p. 68, A. J. Ambrose, Janes, 1983

- Se confecciona un acta con las circunstancias y consecuencias del accidente: 2 soldados muertos, 1 oficial y 9 soldados heridos, y 3 soldados desaparecidos. Ganso Verde, Ítalo Ángel Piaggi, p. 145, Sudamericana/Planeta, 1986

- Van Der Bijl (1999) pp. 141

- Dale (2002), pp. 73

- "Italo Angel Piaggi (2001) GANSO VERDE". Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- "Italo Angel Piaggi (2001) GANSO VERDE". Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- "Falleció el Veterano de Guerra Ítalo Ángel Piaggi" (in Spanish). El Malvinense. 1 August 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- Middlebrook (1985), pp. 391

- "No. 49134". The London Gazette (Supplement). 8 October 1982. p. 12831.

- London Gazette

- Fitz-Gibbon (2002) pp. 183–184

- Ferguson, Greg (1998). The Paras, 1940–1984. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 43. ISBN 9780850455731.

- The Falklands War, Paul Eddy, Magnus Linklater, p. 238, André Deutsch, 1982

- Argentina's Falklands War Veterans. 'Cannon Fodder in a War We Couldn't Win'. By Jens Glüsing, Spiegel.de, 4 March 2007

- Confirman el juzgamiento por torturas en Malvinas (in Spanish), Clarín, Buenos Aires, 27 June 2009

- Centro de Ex Soldados Combatientes en Malvinas de Corrientes Archived 7 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- "Categorized | Feature, Human Rights The Enemy Within Investigating Torture in the Malvinas. By Marc Rogers". Archived from the original on 30 October 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- "Sigue estancada la investigación por torturas en Malvinas". Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

Sources

- Adkin, Mark (2003). Goose Green – A battle is Fought to be Won. London: Cassell. ISBN 0304354961.

- Andrada, Benigno (1983). Guerra aérea en las Malvinas. Ed. Emecé. ISBN 950-04-0191-6. (in Spanish)

- Harclerode, Peter (1 May 1993). Para!: Fifty Years of the Parachute Regiment (Reprint ed.). Arms and Armour. ISBN 1-85409-097-6.

- Fitz-Gibbon, Spencer (1995). Not Mentioned in Dispatches: The History and Mythology of the Battle of Goose Green. Lutterworth Press. ISBN 0-7188-2933-6.

- Kenney Oak, David J. 2 Para's Battle for Darwin Hill and Goose Green. Square Press April 2006. ISBN 0-9660717-1-9.

- Middlebrook, M. (1989). The Fight for the Malvinas: The Argentine Forces in the Falklands War. Viking. ISBN 0-14-010767-3.