Battle of Baguashan

The Battle of Baguashan (Chinese: 八卦山戰役), the largest battle ever fought on Taiwanese soil, was the pivotal battle of the Japanese invasion of Taiwan. The battle, fought on 27 August 1895 near the city of Changhua in central Taiwan between the invading Japanese army and the forces of the short-lived Republic of Formosa, was a decisive Japanese victory, and doomed the Republic of Formosa to early extinction. The battle was one of the few occasions on which the Formosans were able to deploy artillery against the Japanese.[1]

| Battle of Baguashan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Japanese Invasion of Taiwan (1895) | |||||||

The battle of Baguashan martyr's memorial park. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 15,000 | 5,000, with fire support from Bagua battery | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Light | Heavy | ||||||

Background

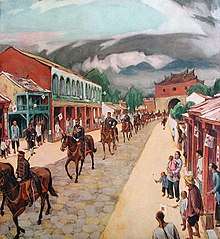

Following the capture of Miaoli, the last Formosan stronghold in northern Taiwan, the Imperial Japanese Army advanced south towards Changhua, the largest city in central Taiwan and the gateway to southern Taiwan. The city was surrounded by hills that offered strong defensive positions, and was protected by the Bagua Battery (八卦砲台) on the heights of Baguashan (Chinese and Japanese: 八卦山; rōmaji: Hakkezan), which was one kilometer east of the city. Changhua was also defended by walls, which was by no means usual at this period. Rebellions were frequent in Taiwan, and the Qing government preferred to keep Taiwanese cities unwalled.

The vanguard units of the IJA reached the north bank of Dadu River on August 25, and immediately began preparation for crossing the river. In anticipation of a large scale confrontation, both sides tried to gather as many forces and supplies as possible. However, due to internal strife, the Formosans could only muster around 5,000 men, many of whom were remnants of militia units that were defeated in Miaoli, or raw recruits from Changhua; President Liu Yongfu ignored the repeated requests for reinforcement due to political rivalry with Li Jingsong (黎景嵩), the commander-general of northern Taiwan.[2] The Japanese massed about 15,000 soldiers, with support of modern artillery. On August 27, General Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa, commander of the Japanese forces in the area, inspected the front line at the bank to draw plan for an assault on the Formosan positions. He was spotted by the garrison in Bagua battery, who opened fire on him and his group of staff. The unexpected bombardment killed his second-in-command and wounded him; some sources alleged that the wound he received later cost him his life.

The battle

After nightfall on August 27, under the cover of darkness, several Japanese units crossed the river and moved into positions to attack. Unaware of the Japanese movement, the Formosans launched several raids against the Japanese that night, but achieved little. The Japanese left wing successfully reached the foot of Mount Baguashan undetected, and assaulted the battery at dawn. Despite being caught off guard and outnumbered, the Formosans held the battery until Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), who was in charge of defense of the battery, was killed, and the garrison reduced to several dozen soldiers. A counterattack by a Black Banner unit was repulsed, and the remaining Formosans under Hsu Hsiang (徐驤) were forced to abandon the battery.

At the same time, Formosan units under Wu Peng-nien (吳彭年) engaged the Japanese in fierce fighting south of the river. Upon learning the loss of Bagua battery, Wu immediately led his men towards the battery and regrouped with Hsu. They then counterattacked the Japanese forces on Mount Baguashan in a last-ditch effort to destabilize the Japanese line, but were eventually thrown back with heavy losses. Wu was killed when his unit was surrounded by the Japanese, and Hsu managed to break out with a handful of men.

After routing the Formosans, the Japanese bombarded the city of Changhua, caused panic among the civilians and garrison soldiers, who then fled the city. The Japanese then took the city unopposed, thus ended the fiercest battle in the history of Taiwan.

The following account of the battle was given by James Davidson, who served as a war correspondent with the Japanese army during the campaign:

Changwha, a walled city, is situated less than five miles from the sea, in a plain scarcely above its level. To the east lies a range of hills, the highest of which—Hakkezan (Paquasoan)—which dominated the whole plain, was crowned with a well-erected fort protected by four 12-centimetre late model Krupp guns, besides a large number of the usual miscellaneous relics of ancient warfare so beloved by the Chinese. To the north, about 3,000 metres distant, ran a mountain stream which, with the heavy rains usual at this time of year, had been converted into a surging river. It was on the opposite banks of this river that the Japanese and Chinese troops met on the 27th; the Japanese to the north hidden by fields of sugar-cane, which cover the district; the Chinese to the south protected by earth-works of some importance, which they had erected on the river bank; while a few rods to the rear stood formidable breastworks.

It has always been the custom to ford the river at one point where it was comparatively shallow, and it was at this point that the Chinese had built their defences and gathered a large portion of their forces; for, if it "blong olo custom" to cross at this place, the Japanese would, according to Chinese reasoning, do the same. But the Japanese have a reputation for dropping old customs, and they did so in this case. The right wing, under command of Major-General Ogawa, remained at the camp to divert the Chinese with large camp fires, etc.; while the left wing, under command of Major-General Yamane, under the shadow of darkness, crossed the river with considerable difficulty at a previously discovered ford some 1,500 metres off. The column was now divided into three detachments. The first detachment, under command of Major-General Yamane, made its way quietly along to obtain a position to attack the city of Changwha itself. The second detachment with a battery of mountain-guns crawled along through the sugar-cane to cross the lower hills and gain a position to the east of the lofty fort of Mount Hakkezan, while the third with great caution slowly and quietly advanced to the rear of the Chinese troops guarding the river, and between them and the city.

The whole force arrived at their positions without a hitch, and with the enemy still watching the moving figures and the numerous camp fires of the Japanese across the river. It was one of the cleverest exhibitions of strategy displayed during the whole war. The right column crossed the river before daylight, leaving a detachment at the camping grounds to keep up the camp fires; and all were now in position ready for the attack. With the first rays of morning, the Chinese were on the alert, and opened fire with great bravado on the decoy troops left across the river. This was to the Japanese the signal for action. Scarcely had the smoke cleared away when the detachment which had occupied the position to the rear of the Chinese on the river bank was down on the insurgents with a rush. The Chinese, too surprised to make any defence, were terror-stricken. They jumped into the river, ran right and left, even on to the bayonets of their opponents. Simultaneously, the second detachment began to climb the hill at the back of the fort of Hakkezan. The surprised garrison poured a rifle fire upon them, but the detachment did not hesitate. On the contrary, bayonets were fixed and a determined charge made, until the fort was entered, and the Chinese deserting the big guns still loaded, were climbing over the walls and plunging down the hillside in full flight.

Many of the retreating insurgents had fled into the walled city of Changwha, apparently with the idea of fighting from the walls, where a large force was now assembled. But the Japanese in the fort above them had witnessed the whole scene and turned the insurgents’ own guns down upon the city. The Chinese had not thought of this; but like a flash their danger became apparent; and from a position of calm defiance, they were thrown into a frenzy of terror, and with a wild rush they sought escape through the South Gate. But to their horrible dismay, they found the Japanese even there; and turning back into the city they ran shrieking and howling like an army amok, firing at anything that attracted their attention. Only a few shots had been fired by the Japanese from the fort; and the Japanese infantry then scaled the walls and poured down into the city in large numbers. Street fighting with the panic-stricken braves occupied an hour; but by 7 a.m. all was quiet. Detachments were at once detailed to pursue the retreating insurgents, who had gone towards Kagi to the south and Lokang (Rokko) to the west, where they hoped boats could be obtained to carry them to the south of the island.[3]

Aftermath

The battle was an impressive Japanese victory, and foreign observers praised the courage and skill with which the Japanese troops had captured such a strong position so quickly. For the Japanese, the opportunity to defeat the Formosans in a pitched battle was welcomed after the weeks of guerilla fighting they had experienced since the start of their march south from Taipei. The battle put an end to organized resistance against the Japanese in central Taiwan, and ultimately paved the way for the final Japanese advance on Tainan, the last major Formosan stronghold. However, the Japanese were unable to follow up their victory immediately. A severe outbreak of malaria at Changhua in early September 1895 ravaged the Japanese forces, killing more than 2,000 men, and continuing Formosan guerilla attacks kept the Japanese short of supplies. The Japanese temporarily halted their advance, and their inaction gave the Formosans time to regroup and organize an initially successful, but ultimately fruitless, counteroffensive.[4]

Cultural influences

In 1965 a mass grave containing 679 bodies, believed to be those of Formosan fighters, was discovered at the site of battle. The site is now a memorial park, dedicated to those who perished in the battle.[5]

The battle of Baguashan has recently been depicted as the climax to the film 1895 (released in November 2008), based on the life of the Formosan militia commander Wu Tang-hsing.

On 6 May 2006, Democratic Progressive Party's leadership circle proposed the dedication of August 28 as "Taiwanese Resistance of Japan Memorial Day," (台灣人民抗日紀念日)[6] as well as the inclusion of the battle in the history textbooks and having the portraits of leading figures in the battle printed on bank notes. This proposal, however, did not make it to the Legislative Yuan.

See also

Notes

- WTFM CLAN 達人 1895 臺灣獨立戰爭

- 歷史文化學習網 新楚軍與黎景嵩 Archived August 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Davidson (1903), pp. 336–8.

- Takekoshi (1907), p. 89.

- 翁金珠部落格 八卦山1895紀念公園掀熱潮

- 台灣人權資訊網 八卦山之役死傷慘烈 史蹟遭忽略 綠擬推828為抗日紀念日(蘋果日報﹞ Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

References

- Davidson, James Wheeler (1903). The Island of Formosa, Past and Present : History, people, resources, and commercial prospects : Tea, camphor, sugar, gold, coal, sulphur, economical plants, and other productions. London and New York: Macmillan & co. OL 6931635M.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Han Cheung (28 August 2016). "Taiwan in Time: Defending the homeland to the death". Taipei Times. p. 8. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- McAleavy, Henry (1968). Black Flags in Vietnam : The Story of a Chinese Intervention. London, England: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0049510142.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Takekoshi, Yosaburō (1907). Japanese Rule in Formosa. London, New York, Bombay and Calcutta: Longmans, Green, and co. OCLC 753129. OL 6986981M.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)