Bat Creek inscription

The Bat Creek inscription (also called the Bat Creek stone or Bat Creek tablet) is an inscribed stone collected as part of a Native American burial mound excavation in Loudon County, Tennessee, in 1889 by the Smithsonian Bureau of Ethnology's Mound Survey, directed by entomologist Cyrus Thomas. The inscriptions were initially described as Cherokee, but in 2004, similarities to an inscription that was circulating in a Freemason book were discovered. Hoax expert Kenneth Feder says the peer reviewed work of Mary L. Kwas and Robert Mainfort has "demolished" any claims of the stone's authenticity.[1] Mainfort and Kwas themselves state "The Bat Creek stone is a fraud."[2]

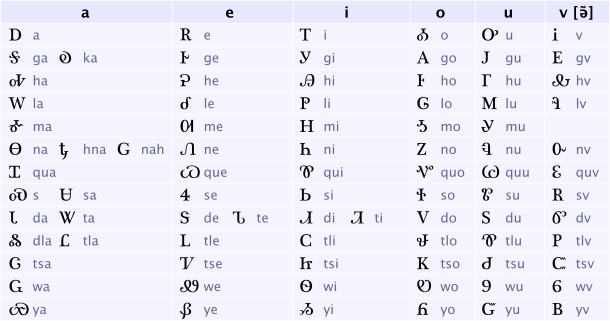

Thomas inaccurately[1] identified the characters on the stone as "beyond question letters of the Cherokee alphabet," a writing system for the Cherokee language invented by Sequoyah in the early 19th century.[3] The stone became the subject of contention in 1970 when Semitist Cyrus H. Gordon proposed that the letters of inscription are Paleo-Hebrew of the 1st or 2nd century AD rather than Cherokee, and therefore evidence of pre-Columbian transatlantic contact.[4] According to Gordon, five of the eight letters could be read as "for Judea." Archaeologist Marshall McKusick countered that "Despite some difficulties, Cherokee script is a closer match to that on the tablet than the late-Canaanite proposed by Gordon,"[5] but gave no details.

In a 1988 article in Tennessee Anthropologist, economist J. Huston McCulloch compared the letters of the inscription to both Paleo-Hebrew and Cherokee and concluded that the fit as Paleo-Hebrew was substantially better than Cherokee. He also reported a radiocarbon date on associated wood fragments consistent with Gordon's dating of the script. In a 1991 reply, archaeologists Robert Mainfort and Mary Kwas, relying on a communication from Semitist Frank Moore Cross, concluded that the inscription is not genuine paleo-Hebrew but rather a 19th-century forgery, with John W. Emmert, the Smithsonian agent who performed the excavation, the most likely responsible party. In a 1993 article in Biblical Archaeology Review, Semitist P. Kyle McCarter, Jr. stated that although the inscription "is not an authentic paleo-Hebrew inscription," it "clearly imitates one in certain features," and does contain "an intelligible sequence of five letters -- too much for coincidence." McCarter concluded, "It seems probable that we are dealing here not with a coincidental similarity but with a fraud."[6]

Mainfort and Kwas published a further article in American Antiquity in 2004,[7] reporting their discovery of an illustration in an 1870 Masonic reference book giving an artist's impression of how the Biblical phrase "holy to Yahweh" would have appeared in Paleo-Hebrew, which bears striking similarities to the Bat Creek inscription. The General History correctly translates the inscription "Holiness to the Lord," though "Holy to Yahweh" would be more precise. They conclude that Emmert most likely copied the inscription from the Masonic illustration, in order to please Thomas with an artifact that he would mistake for Cherokee.

Geographic and historical context

The Little Tennessee River enters Tennessee from the Appalachian Mountains to the south and flows northward for just over 50 miles (80 km) before emptying into the Tennessee River near Lenoir City. The completion of Tellico Dam at the mouth of the Little Tennessee in 1979 created a reservoir that spans the lower 33 miles (53 km) of the river. Bat Creek empties into the southwest bank of the Little Tennessee 12 miles (19 km) upstream from the mouth of the river. While much of the original confluence of Bat Creek and the Little Tennessee was submerged by the lake, the mound in which the Bat Creek Stone was found was located above the reservoir's operating levels.

In the 1880s, the Smithsonian Institution team led by John W. Emmert conducted several excavations in the lower Little Tennessee valley, uncovering artifacts and burials related to the valley's 18th-century Overhill Cherokee inhabitants and prehistoric inhabitants. The Tellico Archaeological Project, conducted by the University of Tennessee Department of Anthropology in the late 1960s and 1970s in anticipation of the reservoir's construction, investigated over two dozen sites and uncovered evidence of substantial habitation in the valley during the Archaic (8000–1000 BC), Woodland (1000 BC – 1000 AD), Mississippian (900-1600 AD), and Cherokee (c. 1600-1838) periods.[8] The expedition of Hernando de Soto likely visited a village on Bussell Island at the mouth of the river in 1540 and the expedition of Juan Pardo probably visited two villages further upstream (near modern Chilhowee Dam) in 1567.[9]

The Bat Creek site, Smithsonian trinomial designation 40LD24, is a multiphase site with evidence of occupation as early as the Archaic period.[10] According to Emmert, the site consisted of one large mound (Mound 1) on the east bank of the creek and two smaller mounds (Mound 2 and Mound 3) on the west bank. Mound 1—which had a diameter of 108 feet (33 m) and a height of 8 feet (2.4 m)—was located on the first terrace above the river, and is thus now submerged by the reservoir. Mound 2—which had a diameter of 44 feet (13 m) and height of 10 feet (3.0 m)—and Mound 3—which had a diameter of 28 feet (8.5 m) and height of 5 feet (1.5 m)—were both located higher up, on the second terrace. According to Emmert's notes, the Bat Creek Stone was found in Mound 3.[11]

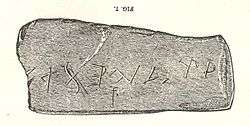

The stone consists of "ferruginous siltstone", and measures 11.4 centimetres (4.5 in) long and 5.1 centimetres (2.0 in) wide.[10] The inscription consists of at least eight characters, seven of which are in a single row, and one located below the main inscription, when held with the straighter edge down. A portion of a ninth letter that has broken off remains at the left edge in this orientation. Two vertical strokes in the upper left corner in this orientation were added by an unknown party while the stone was stored in the National Museum of Natural History, sometime between 1894 and 1970, and were not part of the original inscription.[12]

Archaeological excavations

In 1881, the annual appropriation by Congress for the Smithsonian Institution's Bureau of Ethnology[13] specifically designated that some of the funds be "for archaeological investigations relating to mound-builders and prehistoric mounds."[14] Cyrus Thomas, an entomologist by background, was appointed Director of the Mound Survey. According to archaeologist Kenneth L. Feder, "With this funding, Thomas initiated the most extensive and intensive study yet conducted on the Moundbuilder question. The result was more than seven hundred pages submitted as an annual report of the Bureau in 1894 (Thomas 1894). ... He collected over 40,000 artifacts, which became part of the Smithsonian Institution's collection. ... Thomas's work was a watershed, both in terms of answering the specific question of who had built the mounds, and in terms of the development of American archaeology."[15]

In particular, Thomas addressed the question of whether there were pre-Columbian alphabetically inscribed tablets in the mounds, and emphatically concluded, in part on the basis of the body of evidence his study had collected, that there were not.[16] Thomas also "carefully assessed the claim that some of the mound artifacts exhibited a sophistication in metallurgy attained only by Old World cultures. Not relying on rumors, Thomas actually examined many of the artifacts in question. His conclusion: all such artifacts were made of so-called native copper..."[17] Feder concludes, "With the publication of Thomas's Report on the Mound Explorations of the Bureau of American Ethnology, Moundbuilder archaeology had come of age. Its content was so detailed, its conclusions so reasonable that, though not accepted by all, the myth of a vanished race had been dealt a fatal blow."[18]

Thomas did not excavate the mounds himself, but delegated most of the field work to assistants, including John Emmert, who excavated all three Bat Creek mounds in 1889. He concluded that Mound 1 was little more than a shell deposit. Emmert recorded eight burials in Mound 2—one of which included metal "buckles" and a metal button. His excavation of Mound 3 revealed nine skeletons, seven of which were laid out in a row with their heads facing north, and two more skeletons laid out nearby, one with its head facing north and the other with its head facing south. He reported that the Bat Creek Stone was found under the skull of the south-facing skeleton. Along with the stone were two bracelets identified by both Emmert and Thomas as "copper", as well as fragments of "polished wood" (possibly earspools).[19] A 1970 Smithsonian analysis found that the bracelets were in fact heavily leaded yellow brass.[20] In 1988, radiocarbon dating of the wood spools returned a date of 32–769 AD (i.e., the middle to late Woodland period).[21]

In 1967, the Tennessee Valley Authority announced plans to build Tellico Dam at the mouth of the Little Tennessee River, and asked the University of Tennessee Department of Anthropology to conduct salvage excavations in the Little Tennessee Valley. Litigation and environmental concerns stalled the dam's completion until 1979, allowing extensive excavations at multiple sites throughout the valley. Mound 1 of the Bat Creek Site was excavated in 1975. Investigators concluded that the mound was a "platform" mound typical of the Mississippian period. Pre-Mississippian artifacts dating to the Archaic and Woodland periods were also found. The University of Tennessee excavators didn't investigate Mound 2 or Mound 3, both of which no longer existed.[22] Neither the University of Tennessee's excavation of the Bat Creek Site nor any other excavations in the Little Tennessee Valley uncovered any evidence that would indicate Pre-Columbian contact with Old World civilizations.[23]

Analysis and debate

In his 1894 final report, Thomas published a photograph of the Bat Creek stone, with the straighter edge at the top,[24] along with Emmert's field report on the find, almost verbatim.[25] Thomas himself added the opinion that the letters on it were "beyond question letters of the Cherokee alphabet said to have been invented by George Guess (or Sequoyah), ... about 1821."[26] He in fact had published a more legible lithograph of the stone, in the same orientation, in his earlier book The Cherokees in Pre-Columbian Times, in which he used it as evidence for his short-lived theory that the Cherokee had built the mounds now classified as Middle Woodland.[27]

On the basis of vegetation covering the mound, Thomas concluded that "the evidence seems positive that the mound was at least a hundred years old, and that it was known that it had not been disturbed in sixty years."[28] This would make the mound too old to have contained a Cherokee inscription in 1889. Thomas admitted that as Cherokee, the inscription therefore constituted "a puzzle difficult to solve."[28] He did not provide either a transliteration or a translation of the inscription as Cherokee in either work.

The Bat Creek Stone received scant attention (even in Thomas' later publications) until the 1960s when ethnologist Joseph Mahan, puzzled by Thomas' conclusion that the inscription was Cherokee, sent a photograph of the inscription to Cyrus H. Gordon— a professor of Mediterranean Studies at Brandeis University and a well-known proponent of Pre-Columbian transatlantic contact theories. Gordon published a series of articles in the early 1970s arguing that when the stone is turned so that the straighter edge is at the bottom, the letters are actually a version of Paleo-Hebrew text used in the 1st century BC through the 2nd century AD. According to Gordon, the five letters to the left of the comma-shaped word divider read (right to left) LYHWD, which he interpreted as "for Judea," or, including the broken letter at the far left, LYHWD[M], "for the Jews."[29] Gordon provided only tentative Paleo-Hebrew readings of the other three letters.[30] His findings were published in Newsweek and in newspapers across the nation, sparking a renewed interest in the inscription.[31] In 1979, University of Iowa archaeologist Marshall McKusick argued that "Despite some difficulties, Cherokee script is a closer match to that on the tablet than the late-Canaanite proposed by Gordon."[5] According to McKusick, the inscription actually bore the closest similarities to an early version of Sequoyah's alphabet that was occasionally used before the standard, printed version of the script was developed by Samuel Worcester in 1827.[32] However, McKusick gave no details and made no attempt to interpret the inscription as Cherokee.

The debate was revived in 1988 by J. Huston McCulloch, an economics professor at Ohio State University. In an article in the Tennessee Anthropologist, he compared the letters in the inscription to both Paleo-Hebrew and Cherokee, including the pre-Worcester version favored by McKusick, and concluded that despite admitted difficulties, the fit as Paleo-Hebrew in Gordon's orientation is substantially better than as Cherokee, in either orientation. In this article, McCulloch, also asserts that the "comma" found in the bat creek inscription is a Paleo-Hebrew symbol for word division not known until the discovery of Qumran Leviticus fragments found after World War II. He further reported the radiocarbon date of 32 AD – 769 AD on the wooden earspool fragments, and also that although brass similar to that of the bracelets is a common modern alloy, it also was found in the Roman empire, in particular during the period 45 BC – 200 AD.[33] Later, author Jason Colavito suggested that the mark described as a comma was unnecessary as a word divider as a space between the words already existed. If in fact it was a word divider, Colavito states that the illustration of the Mesha Stele (then known as the "Moabite Stone" in the 1870 Masonic book "demonstrates that the style and shape of the letters, along with word divider marks, were well-known in the 1870s and 1880s and was thus not a twentieth-century discovery." He points out that the "divider on the Bat Creek inscription is correctly placed in the bottom right corner of the word, as it is on the Moabite Stone" and that although the dividers on the actual stone are small circles, the drawing in the book makes some of them appear more like the comma on the Bat Creek stone. He concludes that this does not prove the stone is a hoax, but that there was in fact a source for the word divider early enough to have been used by a hoaxer.[34]

Archaeologists Robert Mainfort and Mary Kwas (1991) replied to McCulloch's article with a number of objections: Relying on an unpublished assessment by Hebrew paleography expert Frank Moore Cross of Harvard University, they concluded the inscription is not legitimate Paleo-Hebrew. Although they conceded that the composition of the brass bracelets is "equivocal with respect to age," they argued that the bracelets are in all likelihood relatively modern European trade items. They interpreted an 1898 statement by Thomas, that "one of the best recent works on ancient America is flawed to some extent" by the depiction of mounds and ancient works "which do not and never did exist" and by the representation of articles which are "modern productions," to be a veiled repudiation by Thomas of his own 1894 Mound Explorations report, and in particular of its Bat Creek inscription. Mainfort and Kwas concluded that the inscription is a forgery, for which Emmert was responsible. They proposed that "Emmert's motive for producing (or causing to have made) the Bat Creek inscription was that he felt the best way to insure permanent employment with the Mound Survey was to find an outstanding artifact, and how better to impress Cyrus Thomas than to 'find' an object that would prove Thomas' hypothesis that the Cherokee built most of the mounds in eastern Tennessee?"[35] The Tennessee Anthropologist discussion continued with McCulloch (1993a) and Mainfort and Kwas (1993).

In an invited article in Biblical Archaeological Review, McCulloch (1993b) reviewed and extended the argument for Paleo-Hebrew. In a reply in the same issue, P. Kyle McCarter, Jr., a professor of Near Eastern Studies at Johns Hopkins University and an expert on the Qumran Copper Scroll, stated that although the inscription "is not an authentic paleo-Hebrew inscription," it "clearly imitates one in certain features," and does contain "an intelligible sequence of five letters – too much for coincidence. It seems probable that we are dealing here not with a coincidental similarity but with a fraud." McCarter remarked that if Emmert forged the inscription in an attempt to ingratiate himself with Thomas by presenting him with a Cherokee inscription, his choice of a paleo-Hebrew model "was ironically inept." [36]

Recent commentary

In 2004 Mainfort and Kwas published a further article in American Antiquity, reporting their discovery of an illustration in an 1870 Masonic reference book that bears striking similarities to the Bat Creek inscription.[37] The Masonic illustration was an artist's impression of how the Biblical phrase "Holy to Yahweh" (qdš.lyhwh) would have appeared in Paleo-Hebrew. Mainfort and Kwas conclude, "There can be little doubt that this was the source of the inscription and that the inscription was copied, albeit not particularly well, by the individual who forged the Bat Creek stone."[38] Although the Bat Creek inscription is not identical to the illustration and although many of the shared commonalities between them amount to generic grammar, Mainfot and Kwas repeat their 1991 contention that Emmert produced the inscription in order to please Thomas with a Cherokee-like artifact, but add that since it is unlikely that Emmert could write Cherokee, he must have copied this Masonic illustration instead, and that the accidental resemblances to Cherokee "were enough to fool Thomas."[39]

In 2014, the Smithsonian Department of Anthropology issued the following statement concerning the stone:

- While recognizing that a diversity of opinion continues to circulate around the authenticity of the Bat Creek Stone, the curators in the Department of Anthropology at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, believe that the inscriptions on the artifact are forgeries and that the artifact is a fake. This opinion is widely shared by other professional archaeologists as represented in the article by Robert Mainfort and Mary Kwas ‘The Bat Creek Stone Revisited: A Fraud Exposed’, American Antiquity 2004. Along with other known fraudulent artifacts, we retain it in our collections as part of the cultural history of archaeological frauds, which were known to be quite popular in the second half of the 19th century.[40]

Current location

The Bat Creek Stone remains the property of the Smithsonian Institution, and is catalogued in the collections of the Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, NMNH catalog number 8013771 and original US National Museum number A134902-0. From August 2002 to November 2013, it was on loan to the Frank H. McClung Museum at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.[41] It has subsequently been loaned to the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in Cherokee, N.C., where it has been on display since 2015.[42]

See also

- Grave Creek Stone

- Mound builders

- Newark Holy Stones

- Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact

- Smithsonian Bureau of American Ethnology (Smithsonian Bureau of Ethnology until 1897)

- Theory of Phoenician discovery of the Americas

- Yehud coinage

References

- Feder, Kenneth L. (2010-10-11). Encyclopedia of Dubious Archaeology: From Atlantis to the Walam Olum. ABC-CLIO. pp. 39–. ISBN 9780313379192. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- Mainfort, Jr., Robert C.; Kwas, Mary L. "The Bat Creek Fraud: A Final Statement". Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- Thomas (1894: 393).

- Gordon (1971, Appendix).

- McKusick (1979: 139).

- McCarter (1993:55).

- Mainfort, Robert C., and Mary L. Kwas, "The Bat Creek Stone Revisited: A Fraud Exposed," American Antiquity 64 (Oct. 2004): 761-769

- Chapman (1985).

- Hudson (2005: 106-107)

- Mainfort and Kwas (1991: 3).

- Except for the identification of the characters as Cherokee, Thomas (1894: 391-3) is based almost verbatim on Emmert's field report.

- McCulloch (1988: 96). These strokes were not present in either the lithograph of Thomas (1890) or the photograph of Thomas (1894:394), but do appear in a 1970 Smithsonian photograph published by Gordon (1971).

- The name was later changed to the Bureau of American Ethnology

- Smithsonian Institution Archives (1881).

- Feder (1999: 144).

- Feder(1999: 145–8).

- Feder (1999:150).

- Feder (1999: 151).

- Thomas (1894: 391–3).

- McCulloch (1988: 104-7).

- McCulloch (1988: 107–10), Beta Analytic-24483/ETH-3677.

- Schroedl (1975: 103)

- Chapman (1985: 97–103).

- Thomas(1894: 394)

- Thomas(1894: 391–3)

- Thomas (1894:393).

- Thomas (1890: 35-7).

- Thomas (1894: 714).

- Gordon (1971: 175–87). Chicago lawyer and author Henriette Mertz (1964) had already suggested the stone as it appeared in Thomas' report was upside down and that the inscription was Semitic, but believed it to be Phoenician.

- See discussion of these letters in McCulloch (1988).

- "A Canaanite Columbus?" Newsweek 76 (17):65, 1970.

- McKusick (1994).

- McCulloch (1988)

- Colavito, Jason (16 May 2018). "The Mesha Stele: A Source for the Bat Creek Stone's "Word Divider"?". Jason Colavito. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- Mainfort and Kwas (1991: 12).

- McCarter (1993: 55). See also several letters to the editor by Robert Stieglitz, McCarter, Mainfort and Kwas, McKusick, McCulloch and others in the Nov./Dec. 1993 and Jan./Feb. 1994 issues of Biblical Archaeology Review.

- Mainfort and Kwas (2004), Macoy (1868: 134). The same illustration appears on p. 169 of the 1870 edition cited by Mainfort and Kwas, as well as the 1989 reprint edition, but not in the 1867 edition.

- Mainfort and Kwas (2004: 765).

- Mainfort and Kwas (2004: 766).

- E-mail dated Feb. 7, 2014 from Jake Homiak, Director, Anthropology Collections & Archives Program, Smithsonian Museum Support Center, Suitland MD, to Barbara Duncan, Education Director, Museum of the Cherokee Indian, Cherokee NC.

- Per Timothy E. Baumann, Curator of Archaeology, McClung Museum.

- Per Barbara Duncan, Education Director, Museum of the Cherokee Indian.

Sources

- Chapman, Jefferson. Tellico Archaeology: 12,000 Years of Native American History Norris, Tenn.: Tennessee Valley Authority, 1985

- Faulker, Charles H. The Bat Creek Stone. Tennessee Anthropological Association, Miscellaneous Paper No. 15, 1992. Reprints pp. 391–3 of Thomas (1894), McCulloch (1988), and Mainfort and Kwas (1991), with introduction by Faulkner.

- Feder, Kenneth L. Frauds, Myths and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology, 3rd ed. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Co., 1999.

- Gordon, Cyrus H. Before Columbus: Links Between the Old World and Ancient America. New York: Crown Publishers, 1971.

- Hudson, Charles. The Juan Pardo Expeditions: Explorations of the Carolinas and Tennessee, 1566-1568. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 2005.

- Mainfort, Robert C., Jr. and Mary L. Kwas. "The Bat Creek Stone: Judeans in Tennessee?" Tennessee Anthropologist 16 (Spring 1991): 1-19. Reprinted in Faulkner (1992). (archived on Wayback Machine)

- Mainfort, Robert C., Jr. and Mary L. Kwas. "The Bat Creek Fraud: A Final Statement," Tennessee Anthropologist 18 (Fall 1993): 87-93. (archived on Wayback Machine)

- Macoy, Robert, General History, Cyclopedia and Dictionary of Freemasonry, Masonic Publishing Co., New York, 3rd ed., 1868, p. 134. (Same illustration appears on p. 169 of 1870 ed. and 1989 reprint ed., but not in 1867 ed.)

- McCarter, P. Kyle, Jr. "Let's be Serious About the Bat Creek Stone," Biblical Archaeology Review 19 (July/Aug. 1993): 54-55, 83.

- McCulloch, J. Huston. "The Bat Creek Inscription: Cherokee or Hebrew?" Tennessee Anthropologist 13 (Fall 1988): 79-123. Reprinted in Faulkner (1992).

- McCulloch, J. Huston (1993a). "The Bat Creek Stone: A Reply to Mainfort and Kwas," Tennessee Anthropologist 18 (Spring 1993): 1-26.

- McCulloch, J. Huston (1993b). "Did Judean Refugees Escape to Tennessee?" Biblical Archaeology Review 19 (July/Aug. 1993): 46-53, 82-83.

- McKusick, Marshall. "Canaanites in America: A New Scripture in Stone?" Biblical Archaeologist, Summer 1979, pp. 137–40.

- McKusick, Marshall. "The Cherokee Solution to the Bat Creek Enigma," Biblical Archaeology Review, 20 (Jan./Feb. 1994): 83-84, 86.

- Mertz, Henriette. The Wine Dark Sea: Homer's Heroic Epic of the North Atlantic. Chicago: Mertz, 1964. ASIN B0006CHG68.

- Schroedl, Gerald F. Archaeological Investigations at the Harrison Branch and Bat Creek Sites. University of Tennessee, Department of Anthropology, Report of Investigations No. 10, 1975.

- Smithsonian Institution Archives. "Funds for Ethnology and Mound Survey", dated March 3, 1881.

- Thomas, Cyrus H. The Cherokees in Pre-Columbian Times N.D.C. Hodges, New York, 1890.

- Thomas, Cyrus H. "Report on the Mound Explorations of the Bureau of Ethnology", in Twelfth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 1890-91, 1894. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. pp. 391–3 reprinted in Faulkner (1992).

- Robert Macoy, George Oliver. General History, Cyclopedia and Dictionary of Freemasonry (1870). Pp 181

External links

- Bat Creek Tablet National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution. Includes zoomable photograph.

- Catalogue No. A134902-0 in the Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution. (Link appears dead on 1 August 2018 and should be removed in near future.)

- Museum of the Cherokee Indian