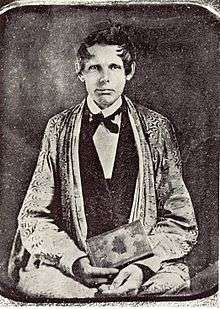

Samuel Worcester

Samuel Austin Worcester (January 19, 1798 – April 20, 1859), was a missionary to the Cherokee, translator of the Bible, printer, and defender of the Cherokee's sovereignty. He collaborated with Elias Boudinot in the American Southeast to establish the Cherokee Phoenix, the first Native American newspaper. The Cherokees gave him the honorary name A-tse-nu-sti, which translates to "messenger" in English.[1]

Samuel Worcester | |

|---|---|

Samuel Worcester, "Cherokee Messenger" | |

| Born | Samuel Austin Worcester January 19, 1798 Peacham, Vermont, U.S. |

| Died | April 20, 1859 (aged 61) |

| Alma mater | University of Vermont |

| Occupation | Minister, linguist, printer, cofounder of Cherokee Phoenix newspaper |

| Spouse(s) | Ann Orr ( m. 1825–1839)Erminia Nash ( m. 1842–1850) |

Worcester was arrested and convicted for disobeying Georgia's law restricting white missionaries from living in Cherokee territory without a state license. On appeal, he was the plaintiff in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), a case that went to the United States Supreme Court. The court held that Georgia's law was unconstitutional. Chief Justice John Marshall defined in his dicta that the federal government had an exclusive relationship with the Indian nations and recognized the latter's sovereignty, above state laws. Both President Andrew Jackson and Governor George Gilmer ignored the ruling.

After receiving a pardon from the subsequent governor, Worcester left Georgia on a promise to never return. He moved to Indian Territory in 1836 in the period of Cherokee removal on the Trail of Tears. His wife died there in 1839. Worcester resumed his ministry, continued translating the Bible into Cherokee, and established the first printing press in that part of the United States, working with the Cherokee to publish their newspaper. In 1963, he was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.[2]

Early life and education

Worcester was born in Peacham, Vermont, on January 19, 1798, to the Rev. Leonard Worcester, a minister. He was the seventh generation of pastors in his family, dating back to ancestors who lived in England. According to Charles Perry of the Peacham Historical Association, Leonard Worcester also worked as a printer in the town. The young Worcester attended common schools and studied printing with his father.[3] In 1819, he graduated with honors from the University of Vermont.[1]

Samuel Worcester became a Congregational minister and decided to become a missionary. After graduating from Andover Theological Seminary in 1823, he expected to be sent to India, Palestine or the Sandwich Islands. Instead, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) sent him to the American Southeast to minister to the local Native American tribes.[4]

Marriage and family

Worcester married Ann Orr of Bedford, New Hampshire, whom he had met at Andover.[1][3] They moved to Brainerd Mission, where he was assigned as a missionary to the Cherokees in August 1825. The goals ABCFM set for them were, "...make the whole tribe English in their language, civilized in their habits and Christian in their religion." Other missionaries working among the Cherokees had already learned that they first needed to learn the Cherokee language. While living at Brainerd, the Worcesters had their first child, a daughter. Two years later, they moved to New Echota, established in 1825 as the capital of the nation on the headwaters of Oostanaula River in what is now Georgia. Worcester worked with Elias Boudinot to establish the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper, the first among Native American nations.[4]

Ultimately Samuel and Ann had seven children: Ann Eliza, Sarah, Jerusha, Hannah, Leonard, John Orr and Mary Eleanor.[3] Ann Eliza grew up to become a missionary and with her husband, William Schenck Robertson, founded Nuyaka Mission in the Indian Territory.[5]

Young Samuel's uncle and namesake, Dr. Samuel Worcester, was the founder of the American Board and had served as the board's official corresponding secretary. The elder Worcester had died at Brainerd in 1821 and was buried there.[6]

Cherokee Phoenix

Worcester was strongly influenced by a young Cherokee named Oowatie (later known by the English name he had been given, Elias Boudinot), who had been educated in New England schools and was the nephew of Major Ridge, a wealthy and politically prominent Cherokee National Council member. The two had become close friends over the two years they had known each other. The Cherokee Sequoyah developed a syllabary to create a writing system for the Cherokee language. This was a singular achievement; no other man is known to have created such a system. He and his people had admired the written papers of the European Americans, which they called the "Talking Leaves."

Boudinot asked Worcester to use his printing experience to establish a Cherokee newspaper. Worcester believed the newspaper could be a tool for Cherokee literacy, and a means to draw the loose Cherokee community together; it would help promote a more unified Cherokee Nation. He wrote a prospectus for the paper that promised to publish laws and documents of the Cherokee Nation, articles on Cherokee manners and customs, as well as "news of the day."[7]

Using his missionary connection, Worcester secured funds to build a printing office, buy the printing press and ink, and cast the syllabary's characters. Since the 86-character syllabary was new, Worcester made the metal type for each character.[8] The two men helped produce the Cherokee Phoenix, which first rolled off the press on February 21, 1828 at New Echota (now Calhoun, Georgia).[7] This was the first Native American newspaper to be published.

At some point, the Cherokees honored Worcester with a Cherokee name, "A-tse-nu-tsi", meaning "messenger."[1]

Worcester in court and prison

The westward push of European-American settlers from coastal areas continued to encroach on the Cherokee, even after they had made some land cessions to the US government. With the help of Worcester and his sponsor, the American Board, they made a plan to fight the encroachment by using the courts. They wanted to take a case to the US Supreme Court to define the relationship between the federal and state governments, and establish the sovereignty of the Cherokee nation. No other civil authority would support Cherokee sovereignty to their land and self-government in their territory. Hiring William Wirt, a former U.S. Attorney General, the Cherokee tried to argue their position before the US Supreme Court in Georgia v. Tassel (the court granted a writ of error for a Cherokee convicted in a Georgia court for a murder occurring in Cherokee territory, though the state refused to accept the writ) and Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) (the court dismissed this on technical grounds for lack of jurisdiction).[9] In writing the majority opinion, Chief Justice Marshall described the Cherokee Nation as a "domestic dependent nation" with no rights binding on a state.[1]

Worcester and eleven other missionaries had met at New Echota and published a resolution in protest of an 1830 Georgia law prohibiting all white men from living on Native American land without a state license.[1] While the state law was an effort to restrict white settlement on Cherokee territory, Worcester reasoned that obeying the law would, in effect, be surrendering the sovereignty of the Cherokee Nation to manage their own territory. Once the law had taken effect, Governor George Rockingham Gilmer ordered the militia to arrest Worcester and the others who signed the document and refused to get a license.[9]

After two series of trials, all eleven men were convicted and sentenced to four years of hard labor at the state penitentiary in Milledgeville. Nine accepted pardons, but Worcester and Elizur Butler declined their pardons, so the Cherokee could take the case to the Supreme Court. William Wirt argued the case, but Georgia refused to have a legal counsel represent it, claiming that no Indian could drag it into court. In its late 1832 decision, the Court ruled that the Cherokee Nation was independent and only the federal government had the authority to deal with Indian nations. It vacated the convictions of Worcester and Butler. President Andrew Jackson, who favored Indian Removal, ignored the ruling by continuing to lobby Congress for a new treaty with the Cherokee, and Governor Gilmer continued to hold the two men prisoner.[9]

Wilson Lumpkin assumed the governorship early the next year. Faced with the Nullification Crisis in neighboring South Carolina, he chose to free Worcester and Butler if they agreed to minor concessions. Having won the Supreme Court decision, Worcester believed that he would be more effective outside prison and left. He realized that the larger battle had been lost, because the state and settlers refused to abide by the decision of the Supreme Court. Within three years, the US used its military to force the Cherokee Nation out of the Southeast and on the "Trail of Tears" to lands west of the Mississippi River.

Later life in Indian Territory

After being released, Worcester and his wife determined to move their family to Indian Territory to prepare for the coming of the Cherokee under removal. In 1835 he and his family moved to Tennessee, where they lived a short while before beginning their major trip by flatboat and steamer in 1836. They lost much of their household goods when a steamer sank. The journey to Dwight Presbyterian Mission in Indian Territory took seven weeks, during which Ann contracted a fever.[10]

After reaching Dwight Presbyterian Mission, Worcester continued to preach to the Cherokees who had already moved to Indian Territory (they were later known within the nation as the Old Settlers, in contrast to the new migrants from the Southeast).[3] In 1836, they moved to Union Mission on Grand River, then finally to Park Hill. His work included setting up the first printing press in that part of the country, translating the Bible and several hymns into Cherokee, and running the mission. In 1839, his wife Ann died; she had been serving as assistant missionary. He remained in Park Hill, where he remarried Erminia Nash in 1842.[1][3]

Worcester worked tirelessly to help resolve the differences between the Georgia Cherokee and the "Old Settlers", some of whom had relocated there in the late 1820s. On April 20, 1859, he died in Park Hill, Indian Territory.

Worcester House

Worcester House is the only surviving original house on the land of the former Cherokee community of New Echota. The rest of the original buildings were destroyed by settlers after the Cherokee were forced by the federal government under Indian Removal to leave Georgia on the "Trail of Tears" in the late 1830s. The house was constructed in 1828 as a two-story building.

The Worcesters lived in the house from 1828 until 1834. It was confiscated by a Georgian who obtained title in the 1832 Land Lottery. The house was owned by many Georgians through the years until 1952. The house was turned over to the state of Georgia, and in 1954 to the Georgia Historical Commission. It is currently managed by the Georgia State Parks and Historic Sites, a division of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. In 1962, the New Echota Historic Site was opened to the public; it preserves the restored Worcester House as an important symbol of New Echota and Cherokee civilization.

See also

- Brainerd Mission

- Daniel Sabin Butrick (Buttrick)

References

- Richard Mize, "Worcester, Samuel Austin (1778-1859)." Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Accessed March 29, 2013.

- "Hall of Great Westerners". National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- About North Georgia, "Samuel Austin Worcestor"

- Langguth, p. 74

- Foreman, Carolyn Thomas. "Augusta Robinson Moore: A Sketch of Her Life and Times," in Chronicles of Oklahoma. vol. 13 No. 4. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- "Samuel Austin Worcester." About North Georgia.

- Langguth, p. 76.

- Langguth, p. 75.

- "'Worcester v. Georgia' (1832)", The New Georgia Encyclopedia.

- Langguth, p. 265

Sources

- Bass, Athea, Cherokee Messenger, University of Oklahoma Press (1936), ISBN 0-8061-2879-8.

- Langguth, A. J. Driven West: Andrew Jackson and the Trail of Tears to the Civil War. New York, Simon & Schuster. 2010. ISBN 978-1-4165-4859-1.

- McLoughlin, William G., The Cherokees and Christianity, 1794-1870: Essays on Acculturation and Cultural Persistence, University of Georgia Press (December 1994), ISBN 0-8203-1639-3.

- New Echota Self-Guiding Trail, Georgia State Parks and Historic Sites (www.gastateparks.org).

- Joseph C. Burke, "The Cherokee Cases: A Study in Law, Politics, and Morality,", 21 Stanford Law Review: 500 (1969).

External links

- "Samuel Worcester", New Georgia Encyclopedia

- "Samuel Austin Worcester", Oklahoma Historical Society

- New Echota Historic Site

- New Echota Historic Site, Georgia State Parks

- Worcester, Samuel A. "Account of S[amuel] A. Worcester's second arrest, 1831 July 18 / S[amuel] A. Worcester". Southeastern Native American Documents, 1730-1842. Tennessee State Library and Archives. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- "Worcester House Photo Gallery"

- Old and New Testaments Cherokee Bible Project

- Dr. Elizur and Esther Butler Missionaries to the Cherokees historical marker