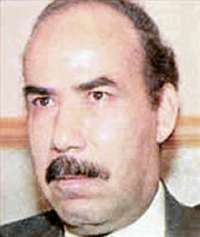

Barzan Ibrahim al-Tikriti

Barzan Ibrahim Hassan al-Tikriti (17 February 1951 – 15 January 2007), also known as Barazan Ibrahim al-Tikriti, Barasan Ibrahem Alhassen and Barzan Hassan[1] (Arabic: برزان إبراهيم الحسن التكريتي; Barzan Mohamed), was one of three half-brothers of Saddam Hussein, and a leader of the Mukhabarat, the Iraqi intelligence service. Despite falling out of favour with Saddam at one time, he was believed to have been a close presidential adviser at the time of his capture. On 15 January 2007, he was hanged for crimes against humanity. The rope decapitated him because wrong measurements were used in conjunction with how far he was dropped from the platform.

Barzan Ibrahim | |

|---|---|

Barzan is the 5 of Clubs in the "Most Wanted" playing card series issued by the US Government | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 17 February 1951 Tikrit, Kingdom of Iraq |

| Died | 15 January 2007 (aged 55) Baghdad, Iraq |

| Cause of death | Hanging |

| Political party | Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Battles/wars | |

High position in Iraqi government

Al-Tikriti was a leading figure in the Mukhabarat, the intelligence service that later turned to another agency performing the duty of Secret Police, from the 1970s, later taking over as director. During his time in the secret police, al-Tikriti played a key role in the Iraqi regime's execution of opponents at home and assassinations abroad. He was also known for his ruthlessness and brutality in purging the Iraqi military of anyone seen as disloyal.[2]

Al-Tikriti became Iraq's representative to the United Nations in Geneva—including the UN Human Rights Committee—in 1989. He was in Geneva for almost a decade, during which he is believed to have managed clandestine accounts for the Iraqi president's overseas fortune.[3] This task was then taken over by a network of foreign brokers, since Hussein had decided that no one in Iraq could be trusted with this task.

U.S. officials characterized al-Tikriti as a member of what they called "Saddam's Dirty Dozen", responsible for torture and mass murder in Iraq. U.S. forces captured him on 17 April 2003. Al-Tikriti was the five of clubs[4] (queen of hearts according to CNN)[5] in the most-wanted Iraqi playing cards.

Post-invasion

Al-Tikriti was among the leadership figures U.S. forces targeted during the Iraq War. In April 2003, warplanes dropped six satellite-guided bombs on a building in the Iraqi city of Ramadi, west of Baghdad, where he was thought to be. In late summer 2003, al-Tikriti was confirmed captured alive by U.S. Army Special Forces with a large entourage of bodyguards in Baghdad. He was turned over to Iraq's Interim Government on 30 June 2004, and was arraigned on 1 July 2004.

Trial and courtroom charges

Barzan Mohamed's trial started on 19 October 2005. He was a defendant in the Iraq Special Tribunal's Al-Dujail trial, and Abd al-Semd al-Husseini was his defence counsel. In a first stage, Al-Tikriti stood trial before a five-judge panel for the Dujail Massacre. He was charged for crimes against humanity, simultaneously with seven other former high officials (Taha Yassin Ramadan, Saddam Hussein, Awad Hamed al-Bandar, Abdullah Kadhem Roweed Al-Musheikhi, Ali Daeem Ali, Mohammed Azawi Ali and Mizher Abdullah Roweed Al-Musheikhi). They were said to have ordered and overseen the killings, in July 1982, of more than 140 Shiite men from Dujail, a village 35 miles north of Baghdad. The men were allegedly killed in retribution after an 8 July 1982 attack on the presidential motorcade as it passed through the village. It was alleged that, apart from the killings, hundreds of women and children from the town were jailed for years in desert internment camps, and that the date palm groves, which sustained the local economy and were the families' livelihood, were destroyed.[6]

During the first court session on 19 October 2005, al-Tikriti pleaded not guilty. During his trial, he was known for his angry outbursts in court and was ejected on several occasions.[2]

In the weeks following the first audience, serious security concerns for the defense team of Hussein and the other accused became apparent. On 21 October 2005, 36 hours after the first hearing, a group of unidentified armed men dragged one of the attorneys from his office in east Baghdad and shot him dead. A few days later, a second lawyer was killed in a drive-by shooting, and a third, injured in that attack, subsequently fled Iraq for sanctuary in Qatar.

As a result, calls for the trial to be held abroad were heard. The defense lawyers, supported by the Iraqi Bar Association, imposed a boycott on the trial until their security concerns were met with specific measures. A few days before the trial was to resume, the defense team announced that it had accepted offers of protection from Iraqi and U.S. officials and would appear in court on 28 November 2005. The agreement is said to have included the same level of protection that is offered to the Iraqi judges and prosecutors, with measures such as armored cars and teams of bodyguards.[6]

After a short court session on 28 November 2005, during which some testimony regarding the killings in Dujail was presented, Judge Rizgar Mohammed Amin ordered a one-week adjournment until 5 December, to grant the defence teams time to find new counsel.

On 12 March 2006, the prosecutor announced that if Hussein and his seven co-defendants were sentenced to death in the Dujail case, the sentence would be carried out as soon as possible. Thus, the other cases for which they were indicted would not be heard in court. On 19 June 2006, the prosecutor asked the court, in his closing arguments, that the death penalty be imposed upon al-Tikriti, Hussein, and Ramadan.

On 5 November 2006, al-Tikriti was sentenced to death by hanging.

Appeals

A death sentence or life imprisonment generates an automatic appeal. On 3 December 2006, the defence team lodged an appeal against the verdicts for al-Tikriti, Hussein, and al-Bander, who had been sentenced to death. On 26 December 2006, the appeals chamber confirmed the verdict and the death sentence against al-Tikriti.

In November 2006, Iraqi President Jalal Talabani appealed for al-Tikriti to be moved to medical facilities to receive treatment for his spinal cancer. Al-Tikriti originally made an appeal from his cell to U.S. President George W. Bush and to Talabani for treatment, referring to the latter as an "old friend".[7]

Execution

On 15 January 2007, the death sentence was carried out. Al-Tikriti, along with co-defendants Hussein and the former Chief Justice of the Iraqi Revolutionary Court al-Bandar, were sentenced to death by hanging. He was originally scheduled to hang on 30 December with Hussein (as he and al-Bandar wished) but due to the Eid, lack of time, and lack of a helicopter to deliver them, as well as international pressure, the hangings were postponed to 15 January. Al-Tikriti's sentence was carried out at 03:00 local time (00:00 UTC) on 15 January 2007. His death was confirmed at 3:05/00:05 UTC.[8][9] Barzan was decapitated by the long drop, the accidental result of the hangman using a rope that was too long.[10][11] Al-Tikriti's and al-Bandar's counsel was not allowed to attend, as was the case with Hussein's hanging.

Reaction to the execution

On 15 January, U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice said in a news conference with the Egyptian foreign minister:[12] "We were disappointed there was not greater dignity given to the accused under these circumstances."

In a press briefing by British Prime Minister Tony Blair's official spokesman, in response to a question as to what Blair's reaction was to the "botched hanging" in Iraq, the spokesman said:[13] "In terms of the death penalty in Iraq, our position on the death penalty is well known, and we had made that position known to the Iraqi Government again since the death of Saddam Hussein. However, Iraq is a sovereign Government, and therefore has a right under international law to decide its own policy on the death penalty."

Al-Tikriti's son-in-law, Azzam Saleh Abdullah, said:[12] "We heard the news from the media. We were supposed to be informed a day earlier but it seems that this government does not know the rules." He said the execution reflected the hatred felt by the Shiite-led government: "They still want more Iraqi bloodshed. To hell with this democracy."

Family

- Ilham Khairillah Tulfah al-Tikriti (wife)

- Mohamed Barzan Ibrahim Hasan al-Tikriti (son)

- Saja Barzan Ibrahim Hasan al-Tikriti (daughter)

- Ali Barzan Ibrahim Hasan al-Tikriti (son)

- Noor Barzan Ibrahim Hasan al-Tikriti (daughter)

- Khawla Barzan Ibrahim Hasan al-Tikriti (daughter)

- Thoraya Barzan Ibrahim Hasan al-Tikriti (daughter)

See also

- Omar al-Tikriti – Barzan Ibrahim al-Tikriti's nephew

- Execution of Saddam Hussein

- Capital punishment in Iraq

- Hanging – section on "long drop" method

References

- "Cable reveals details about Saddam Hussein's 'hastily run' execution". CNN. 7 December 2010.

- "Obituary: Barzan Ibrahim Hasan al-Tikriti". BBC News. 15 January 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "Barzan Ibrahim Al-Tikriti". The Independent. 16 January 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "IRAQI "MOST WANTED" PLAYING CARDS". Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "U.S. issues most wanted list". CNN. 11 April 2003. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "Barzan Ibrahim Hassan al-Tikriti". Trial International. 2 May 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "Talabani fails in bid to secure medical treatment for Barzan Tikriti". ekurd.net. 23 November 2005. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "Hussein trial 'fundamentally unfair'". CNN. 5 November 2006. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "Lawyer: Two Saddam aides hanged". China Daily. 15 January 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- McElroy, Damien; Blair, David (16 January 2007). "Outrage as Saddam's half-brother is decapitated at his hanging". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "Saddam Hussein's top aides hanged". BBC News. 15 January 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- Rudolf Siebert (2010). Manifesto of the Critical Theory of Society and Religion (3 vols.): The Wholly Other, Liberation, Happiness and the Rescue of the Hopeless. 1. Brill. p. 577. ISBN 978-90-04-18436-7. ISSN 1573-4234. OCLC 1030351098.

- "Botched hanging draws criticism from international community". Malaysia Sun. Midwest Radio Network. 15 January 2007. Archived from the original on 21 January 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

External links

- globalsecurity article on Barzan Ibrahim El-Hasan al-Tikriti

- Saddam’s Half-Brother Barzan Al-Tikriti Captured by DEBKAfile, 20 April 2003

.jpg)