Barton Cylinder

The Barton Cylinder is a Sumerian creation myth, written on a clay cylinder in the mid to late 3rd millennium BCE, which is now in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Joan Goodnick Westenholz suggests it dates to around 2400 BC (ED III).[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

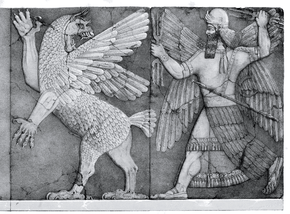

Chaos Monster and Sun God |

|

Seven gods who decree

|

|

Other major deities |

|

Demigods and heroes

|

| Related topics |

Description

The cylinder is inscribed with a Sumerian cuneiform mythological text, found at the site of Nippur in 1889 during excavations conducted by the University of Pennsylvania. The cylinder takes its name from George Barton, who was the first to publish a transcription and translation of the text in 1918 in "Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions".[2] It is also referred to as University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Catalogue of the Babylonian Section (CBS) number 8383. Samuel Noah Kramer referred to it as The Nippur Cylinder and suggested it may date as far back as 2500 BC.[3] The cylinder dates to the Old Babylonian period, but Falkenstein (1951) surmises that the composition was written in Archaic, pre-Ur III cuneiform, likely dating to the Akkad dynasty (c. 2300 BC). He concludes a non-written literary history that was characterised and repeated in future texts.[4] Jan van Dijk concurs with this suggestion that it is a copy of a far older story predating neo-Sumerian times.[5][6]

Content

The most recent edition was published by Bendt Alster and Aage Westenholz in 1994.[7] Jeremy Black calls the work "a beautiful example of Early Dynastic calligraphy" and discussed the text "where primeval cosmic events are imagined." Along with Peeter Espak, he notes that Nippur is pre-existing before creation when heaven and earth separated.[8] Nippur, he suggests is transfigured by the mythological events into both a "scene of a mythic drama" and a real place, indicating "the location becomes a metaphor."[9]

Black details the beginning of the myth: "Those days were indeed faraway days. Those nights were indeed faraway nights. Those years were indeed faraway years. The storm roared, the lights flashed. In the sacred area of Nibru (Nippur), the storm roared, the lights flashed. Heaven talked with Earth, Earth talked with Heaven."[9] The content of the text deals with Ninhursag, described by Bendt and Westenholz as the "older sister of Enlil." The first part of the myth deals with the description of the sanctuary of Nippur, detailing a sacred marriage between An and Ninhursag during which heaven and earth touch. Piotr Michalowski says that in the second part of the text "we learn that someone, perhaps Enki, made love to the mother goddess, Ninhursag, the sister of Enlil and planted the seed of seven (twins of) deities in her midst."[10]

The Alster and Westenholz translation reads: "Enlil's older sister / with Ninhursag / he had intercourse / he kissed her / the semen of seven twins / he planted in her womb"[7]

Peeter Espak clarifies the text gives no proof of Enki's involvement, however he notes "the motive described here seems to be similar enough to the intercourse conducted by Enki in the later myth "Enki and Ninhursag" for suggesting the same parties acting also in the Old-Sumerian myth."[11]

Barton's translation and discussion

Barton's original translation and commentary suggested a primitive sense of religion where "chief among these spirits were gods, who, however capricious, were the givers of vegetation and life." He discusses the text as a series of entreatments and appeals to the various provider and protector gods and goddesses, such as Enlil, in lines such as "O divine lord, protect the little habitation."[2] Barton suggests that several concepts within the text were later recycled in the much later biblical Book of Genesis. He describes Ninhursag in terms of a snake goddess who creates enchantments, incantations, and oils, to protect from demons, saying: "Her counsels strengthen the wise divinity of An", a statement which reveals a point of view similar to that of Genesis 3, (Genesis 3:1) 'Now the serpent was more subtle than any beast of the field." Barton also finds reference to the tree of life in the text, from which he claimed: "As it stands the passage seems to imply a knowledge on the part of the Babylonians of a story kindred to that of Genesis (Genesis 2:9). However, in the absence of context one cannot build on this." Finding yet another parallel with Genesis, Barton mentions that "The Tigris and Euphrates are twice spoken of as holy rivers – and the 'mighty abyss' (or 'well of the mighty abyss') is appealed-to for protection."

His translation reads: "The holy Tigris, the holy Euphrates / the holy sceptre of Enlil / establish Kharsag."

See also

Notes

- Miguel Ángel Borrás; Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (2000). La fundación de la ciudad: mitos y ritos en el mundo antiguo. Edicions UPC. pp. 46–. ISBN 978-84-8301-387-8. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- George Aaron Barton, Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions (Yale University Press, 1918).

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (2007) [1961]. Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C. Forgotten Books. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-60506-049-1.

- Bendt Alster, "On the Earliest Sumerian Literary Tradition," Journal of Cuneiform Studies 28 (1976) 109-126.

- Norsk orientalsk selskap; Oosters Genootschap in Nederland; Orientalsk samfund (Denmark) (1964). van Dijk, J. J. A., Le motif cosmique dans la pensée sumérienne in Acta Orientalia 28, 1-59. Munksgaard. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- Lindsay Jones (2005). Encyclopedia of religion. Macmillan Reference USA. ISBN 978-0-02-865743-1. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- Bendt Alster and Aage Westenholz, "The Barton Cylinder," Acta Sumeriologica 16 (1994) 15-46.

- Espak, Peeter. The god Enki in Sumerian Royal Ideology and Mythology, Tartu University Press, 2010

- Thorkild Jacobsen; I. Tzvi Abusch (2002). Jeremy Black in Riches hidden in secret places: ancient Near Eastern studies in memory of Thorkild Jacobsen. Eisenbrauns. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-1-57506-061-3. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- Jiří Prosecký (1998). Piotr Michalowski in Intellectual life of the Ancient Near East: papers presented at the 43rd Rencontre assyriologique international, Prague, July 1–5, 1996, p. 240. Oriental Institute. ISBN 978-80-85425-30-7. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- Espak, Peeter., Ancient Near Eastern Gods Ea and Enki; Diachronical analysis of texts and images from the earliest sources to the neo-sumerian period, Masters thesis for Tartu University, Faculty of Theology, Chair for Ancient Near Eastern Studies, 2006.

Further reading

- Alster, Bendt. 1974. "On the Interpretation of the Sumerian Myth 'Inanna and Enki'". In Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 64. 20-34.

- Krecher, Joachim. 1992. UD.GAL.NUN versus "Normal" Sumerian: Two Literatures or One?. In Pelio Fronzaroli, Literature and Literary Language at Ebla (Quaderni di semitistica 18). Florence: Dipartimento di Linguistica, Università di Firenze

- Bauer, Josef. 1998. Der vorsargonische Abschnitt der mespotamischen Geschichte. In Pascal Attinger and Markus Wäfler, Mesopotamien: Späturuk-Zeit und frühdynastische Zeit (Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 160/1). Freiburg / Göttingen: Universitätsverlag / Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.