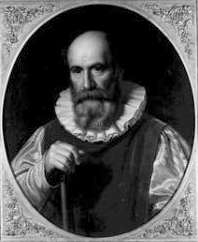

Bartolomeo Maranta

Bartolomeo Maranta, also Bartholomaeus Marantha (1500 – 24 March 1571[1]) was an Italian physician, botanist, and literary theorist.

Bartolomeo Maranta | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1500 or 1514 |

| Died | 24 March 1571 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Botany, Medicine |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Maranta |

The Marantaceae, a family of herbaceous perennials related to the gingers, are named after him.[2] His name was also given to a street in Rome.[3]

Life

Maranta was born in Venosa, in 1500 or 1514, to the lawyer and academic Roberto Maranta, originally from Venosa, and Beatrice Monna, a noblewoman from Molfetta.[4] Having graduated at Naples, around 1550 he moved to Pisa where he became a student of the botanist and physician Luca Ghini.[4][5]

From 1554 to 1556, he worked with the botanical garden of Naples that Gian Vincenzo Pinelli had founded, and around 1568 helped found a botanical garden in Rome.[6]

He was a friend of the naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi, and twenty-two letters from their correspondence survive.[7] Maranta was also both the friend and rival of Pietro Andrea Mattioli. The two competed upon the death of Ghini over which of them would inherit their teacher's papers and herbarium.[8] Maranta died in Molfetta or Melfi.[9]

Medicine and botany

Maranta was physician to the Duke of Mantua and later to Cardinal Branda Castiglioni. He combined his interests in medicine and botany in Methodi cognoscendorum simplicium (1559), in which he organized the subject of botanical pharmacology by nomenclature, species identification, and medicinal properties.[10]

Maranta and other 16th-century naturalists differed from their classical predecessors in allowing empirical evidence to have a direct shaping influence on their work; Maranta wrote that no one could "advance knowledge of simples … without seeing different places and talking to diverse men [who are] experts in their profession."[11]

Among Maranta's most-referenced works is his treatise on antidotes to poisons, Della theriaca et del mithridato, in two volumes (1572). Maranta maintained that theriac had been tested on criminals condemned to death and was proven in antiquity to be infallible. It was also a treatment for all diseases. If theriac failed to produce results, he said, it was because the physicians and pharmacists of his own time lacked the knowledge to compound it.[12] Maranta conducted experiments in the natural history museum of Ferrante Imperato on the proportion of wine needed to dissolve the ingredients for theriac, claiming that "it preserves the healthy" and "cures the sick." But theriac was a controversial drug; in the 1570s, two physicians were expelled from the College of Physicians in Brescia for overprescribing it, and Maranta had to fend off criticism for substituting an ingredient in the formula.[13]

Literary criticism

Maranta's literary theorizing, like that of Aristotle commentator Francesco Buonamici, is often Aristotelian. His major work of literary criticism is Lucullianae quaestiones, in five volumes (1564). One of Maranta's interests is the effects of maraviglia, or "the marvelous," on plot. Torquato Tasso had defined maraviglia in epic as "any virtuous feat that surpassed the ordinary capacity of great men," including miracles, but maraviglia could also derive from verbal artistry and style.[14] Maranta describes the "marvels" of tragedy and epic as that which is "unheard of, new, and beyond expectation."[15]

Like Buonamici, Maranta sought to resist the Renaissance tendency to regard poetry as subject to rhetoric.[16] But of the Italian literary critics, only Maranta makes a point of insisting on the superiority of poetry to both rhetoric and history. In this regard, he has been compared to Philip Sidney, although his work was not likely to have been known by the English poet and critic.[17] Maranta believed that poets were more powerful teachers than philosophers because their discourse is made vivid, rather than abstract, by moving the passions and demonstrating behavior.[18]

References

- Hebrew University Studies in Literature and the Arts 13, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Institute of Languages, Literatures & Arts, 1985, p. 178.

- James Cook University, "Discover Nature," Marantaceae. Archived July 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Google search results, retrieved January 13, 2009.

- M.N. Miletti, "Roberto Maranta", Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani.

- William A. Wallace, "Traditional Natural Philosophy," in The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 224 online.

- Paula Findlen, Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy (University of California Press, 1996), p. 369; French Emblems at Glasgow, "Sambucus, Joannes: Les emblemes (1567)."

- PubMed abstract.

- Paula Findlen, Possessing Nature, pp. 131 and 369.

- Camillo Minieri-Riccio, Memorie storiche degli scrittori nati nel regno di Napoli, Tip. dell'Aquila di V. Puzziello, 1844, p.197

- Andrea Ubrizsy-Savoia, "l'investigation de la nature," in L'Époque de la Renaissance, vol. 4: Crises et essors nouveaux (1560–1610) (John Benjamins, 2000) p. 342 online.

- Paula Findlen, Possessing Nature, p. 175 online.

- R. Palmer, "Pharmacy in the Republic of Venice in the Sixteenth Century," in The Medical Renaissance of the Sixteenth Century (Cambridge University Press, 1985) p. 108 online.

- Paula Findlen, Possessing Nature pp. 226, 242, and 285.

- Daniel Javitch, "Italian Epic Theory," in The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism, vol. 3, p. 209.

- Inaudita, ac nova, & praeter expectationem, p. 89 in the Basel 1564 edition of Lucullianarum quaestionum; Glyn P. Norton with Marga Cottino-Jones, "Theories of Prose Fiction and Poetics in Italy: novella and romanzo," in The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism, vol. 3: The Renaissance (Cambridge University Press, 1999) p. 327 online.

- Gunter Gebauer and Christoph Wulf, Mimesis: Culture, Art, Society, translated by Don Reneau (University of California Press, 1996), p. 81 online.

- Unpublished lectures 1563–64, vol. 1, p. 487, as cited and discussed by Wesley Trimpi, "Sir Philip Sidney's An Apology for Poetry," in The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism (Cambridge University Press, 1999), p. 195, note 12.

- Brian Vickers, "Rhetoric and Poetics," in The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 736 online.

- IPNI. Maranta.

Note: Some information in this article was taken from its counterpart in the French Wikipedia.