Barnsley, Gloucestershire

Barnsley is a village and civil parish in the Cotswold district of Gloucestershire, England, 3.7 miles (6.0 km) northeast of Cirencester. It is 125 kilometres (78 mi) (geodesically) west of London.

| Barnsley | |

|---|---|

Barsnley Village Festival in 2008 | |

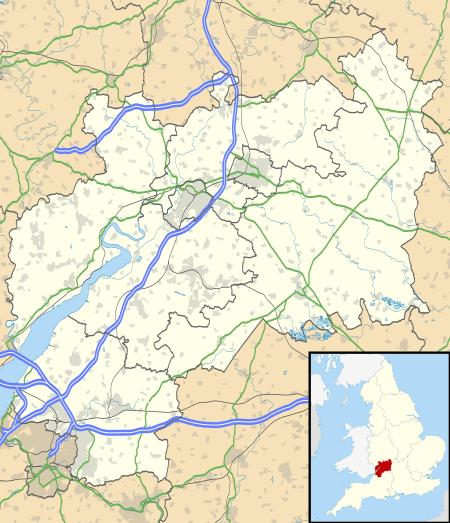

Barnsley Location within Gloucestershire | |

| OS grid reference | SP077050 |

| • London | 80 mi (130 km) E |

| District |

|

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Cirencester |

| Postcode district | GL7 |

| Police | Gloucestershire |

| Fire | Gloucestershire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

History

Barnsley's history dates to the Iron Age settlement in Barnsley Park, later occupied in the 2nd century by a Roman villa. But by 577, after the capture of Cirencester, a Saxon village called Bearmodeslea (Bearmod's glade) existed here.[1] The main building was erected 350-60 AD, but the walls enclosure had been completed by 330 AD. Significant Romano-British occupation took place during the reign of Emperor Trajan. The 'Celtic Fields' so-called covered parkland of about 120 acres. There was a Roman road running through extensive earthwork fortifications northwards to Cadmoor.[2]

The Domesday Book recorded total heads of house or slaves as 24. It was granted to Magaret de Bohun, daughter of the Earl of Hereford by 1180, which she assigned to the monks of Llanthony Priory. After becoming known as Bardesley in 1197. It became part of a Knights fee during the Scottish Wars of Edward I. From 1403 the demesne land was farmed; the large tenanted fields became common pasture, and were later known as Barnsley Wold of 169 acres (0.68 km2) for cow-grazing. The village became royal property under the reign of Henry VIII three hundred years later. Henry was known to let each of his wives solely enjoy the village by turns. During the time of the village's status as royal property, many of its inhabitants earned their living through agriculture, grazing sheep on the 'yardlands' of common mead, helping make the Cotswolds the centre of the wool trade.[3]

During the Reformation the old Barnsley Park was dismantled, the parker dismissed: the Bourchier family became the owners of the village in 1548, thanks to a reversionary grant, and held it for the next two hundred years. The family is responsible for building the village's Barnsley House, Church Cottage and parts of the Church farm. They lived in the centre of the village on the site of the former Nether Court.[4] But in 1700 William married the daughter of the Duke of Chandos, and with the dowry built a new mansion called Barnsley Park. Built in the Baroque style by Henry Perrot and Charles Stanley after Canons, Great Stanmore. Henry Perrot owned the parish in 1762 and enclosed it by private treaty, dividing the land into three farms.[5] By 1778 there were 1,100 sheep on the land and, in season 460 lambs.

Further road building took place in 18th century driving trade to the south of the village. In 1794 the Ablington Road was diverted: the original road went over Wayboll Hill. The Oxford Turpike from 1753 represented a connection with the Welsh Way on the same road to London. Cattle Drovers rested their herds overnight along this route in Barnsley House's field called Ten Acres.[6] But sheep-rearing dominated this part of the Cotswolds. During the 20th century the emphasis gradually shifted to grass and then arable, which came to predominate by 1975.

The village architecture was expanded during 1810-1820 when new cottages were built along the Cirencester-Bibury road when Brereton Bourchier was lord of the manor. Trade such as blacksmith, carpenter and shoemaker thrived with wheelwrights, a butcher and, a village Greyhound Inn. Barnsley's population peaked in 1821 at 318, yet agriculture continued to be the main occupation in 1831 for the 57 families. At that time the Poole family arrived to work as stonemasons. During the First World War, the village had an estimated 200 inhabitants, of which six lost their lives during the war years of 1914–18.[7]

In 2019, the village hit the headlines after Australian snooker player Neil Robertson had to withdraw from qualifying for the World Open due to following sat nav directions to Barnsley instead of Barnsley, South Yorkshire. World Snooker later poked fun at Robertson by sending him a map for the next tournament, the Northern Ireland Open. Robertson's error gave Ian Burns an automatic bye into the next round.

St Mary's Church

The Church of England parish church, dedicated to St Mary, is a Grade II* listed building, of Norman origin but “with subsequent alterations of every century, including substantial restoration of 1843-1847”.[8] An authoritative modern source comments approvingly that, “The Elizabethan tower with its simple gables and finials look pretty by any standard, and the standard at Barnsley is high”.[9]

Local Government

Barnsley deferred to the court at Bibury. The parish was in the past part of the Cirencester Union. It was part of the Cirencester Rural District until 1974 when it was reorganized the Cotswold District. The parliamentary constituency is the Cotswolds or Cirencester. Since 2010 the constituency has been known as The Cotswolds; it has been held since 1992 by Geoffrey Clifton-Brown.

There was a Church of England primary school until 1964, but it closed, and the children sent to Ampney Crucis.

Community

According to the 2001 census the parish had a population of 162, increasing to 209 at the 2011 census.[10]

One of the village's significant features is Barnsley House, with a garden designed by its former resident Rosemary Verey. Barnsley House was built in 1667 by Brereton Bourchier. On the owner's death, her estate was sold and the residential dwelling is now The Barnsley House Hotel. Brereton Bourchier also built the village's Church Cottage and the oldest part of what is now called the Church farm. By the 1660s, with the village's population at about 100, there was also a village inn. The village today has its own church and pub. Since 2009 the inn has become renowned in the Cotswolds for its quality cuisine.[11]

The Barnsley Village Garden Festival was inaugurated in 1998 and has since played host to many horticultural experts.[12] It celebrated its 20th anniversary on 17 May 2008. Saturday, 19 May 2018 will mark the 30th anniversary.[13] It is held in the grounds of the present Lord Faringdon's home of Barnsley Park.

One notable resident is mountaineer Kenton Cool and his family. As of summer 2017, Kenton has reached the summit of Mount Everest twelve times.

References

- "Ancient and Historical Monuments in the County of Gloucester, Iron Age and Romano-British Monuments in the Gloucestershire Cotswolds". London: HMSO. 1976. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- "Ancient and Historical Monuments..." London: Her Majesty's Stationers Office. 1976. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- Glos R.O., D 269B/F 34.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1281-2, p.519; Inq. Post Mortem Glos, 1236-1300, p.135.,

- Rudder, Gloucestershire, p.260; G.D.R., T 1/15.

- Ex inf. M. Wykeham-Musgrave of Barnsley MS. Bodleian Lib., Oxford, 18th C lease 1690.; Glos R.O., D 269B/F 13. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol7/pp13-21.

- "Barnsley War Memorial". Gloucestershire Genealogy. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- British Listed Buildings web-site, accessed on 28 March 2018

- David Verey, Cotswold Churches (B. T. Batsford, 1976), at pages 130-131

- "Snooker champ Neil Robertson's sat-nav blunder after heading to wrong Barnsley for World Open qualifier". Gloucestershire Live. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- http://www.thevillagepub.co.uk/

- Yemm, Helen (28 May 2012). "A Visit to the Gardens of Barnsley, Gloucestershire". Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- "Barnsley Village Festival 2018". Retrieved 24 December 2017.

Further reading

- Gloucestershire: the Cotswolds, The Buildings of England edited by Nikolaus Pevsner, 2nd ed. (1979) ISBN 0-14-071040-X, pp. 96–100

External links

- Barnsley Village, residents' site

- Barnsley House Garden

- Barnsley in the Domesday Book