Barczewo

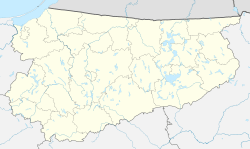

Barczewo [barˈt͡ʂɛvɔ] (until 1946 Wartembork; German: Wartenburg in Ostpreußen) is a town in Olsztyn County, Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, Poland. It is located 20 km NE of Olsztyn, in the historic region of Warmia. The town dates its beginnings from 1325.

Barczewo | |

|---|---|

| |

Coat of arms | |

Barczewo  Barczewo | |

| Coordinates: 53°50′N 20°41′E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | |

| County | Olsztyn |

| Gmina | Barczewo |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4.58 km2 (1.77 sq mi) |

| Population (2016) | |

| • Total | 7,376 |

| • Density | 1,600/km2 (4,200/sq mi) |

| Postal code | 11-010 |

| Website | http://www.barczewo.pl |

Name

The German name of the town ("Wartenburg") has its origins from the town of Wartenburg (Elbe).[1] In Polish the town was known historically as Wartembork, Wartenberg, Wartenbergk, Wathberg, Bartenburg, Warperc, Wasperc, Wartbór or Wartbórz.

In the aftermath of World War II, the town was transferred from Germany to Poland. Commission for the Determination of Place Names decided to change the town's name. It was briefly named Nowowiejsk, after local composer Feliks Nowowiejski, in September 1946. In December that year the Commission settled on another name, Barczewo, honouring Polish national activist who fought against Prussian oppression of Poles in Warmia, Walenty Barczewski (1865–1928).[2]

History

.jpg)

The town was first located in 1325 but was soon after destroyed by Lithuanians. The rebuild town was granted city rights in 1364. In 1466, after the Second Peace of Toruń, the town, then known as "Wartberg",[2] became part of Kingdom of Poland. In 1772, after the First Partition of Poland it was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia.

According to German statistics Poles constituted 72% of population in 1825[3] and 62% in 1861;[4] Gerard Labuda and August von Haxthausen give the number of 1500 Poles and 590 Germans living in the town in 1825.[5][6] The local monastery was secularised in 1810, in 1819/1820 Prussian authorities decided to close down the monastery that was has been described as "the stronghold of Polishness." After the death of Father Tyburcjusz Bojarzynowski, last leader of the monastery, in 1834 it has been converted into a state prison.[1][7] According to Wojciech Zenderowski this was part of Prussian repressions against Poles as the monastery was seen as particularly problematic by Prussian authorities for being a center of Polish resistance.[8]

A Jewish Synagogue was built in 1847, and a Jewish cemetery from the 19th century exists as well.[9] During the January Uprising in 1860s against the Russian Empire, Barczewo was the local centre of supplying medicine, food and even firearms to Polish rebels, with the Polish society in the town becoming active in war effort and led by August Sokołowski.[10] In 1885 a mass rally was organised by Poles, demanding among others that Polish children should be allowed to use their language in education[11] In 1886 a bookstore with Polish books and publications was opened in the town and came into conflict with German authorities who wanted it to remove Polish language signs.[12]

In the plebiscite of 1920 3,020 inhabitants voted to remain in Weimar German East Prussia, 140 votes supported Poland.[2][13] In the interwar era the town was the residence of the fictional Kuba spod Wartemborka, a pseudonym of a figure in Polish press in Warmia created by Seweryn Pieniężny (1890-1940) which ridiculed Germanisation efforts against Poles in the region.[14][15] Polish organisations continued to thrive in the town, up until Second World War; as Nazi party was elected to power in Germany, repressions intensified, eventually many Polish activists were either imprisoned or, like Pieniężny, murdered in Nazi concentration camps and prisons.[2][16] During that war, the remaining Jewish community was murdered in the Holocaust.[9] The town was occupied by Soviet troops without a fight on 31 January 1945. On 22 May 1945 the town, now destroyed at 60%, was handed over to Polish officials.

Historical population

People

- Feliks Nowowiejski (1877–1946), Polish composer

- Robert Pruszkowski (1907–1983), German Roman Catholic priest

- Tomasz Zahorski (born 1984), Polish footballer

Sites of interest

- Barczewo Castle

- Feliks Nowowiejski Museum[19]

References

- Jackiewicz-Garniec, Malgorzata; Garniec, Miroslaw (2009). Burgen im Deutschordensstaat Preussen (in German). p. 76.

- Barczewo.pl Archived April 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (in Polish)

- von Haxthausen, August (1839). Die ländliche verfassung in den einzelnen provinzen der Preussischen Monarchie (in German). Königsberg: Gebrüder Borntraeger Verlagsbuchhandlung. p. 78.

- Zabytkowe ośrodki miejskie Warmii i MazurLucjan Czubiel, Tadeusz Domagała, page 81, 1969

- Historia Pomorza: (1815-1850)gospodarka, społeczeństwo, ustrójGerard Labuda Poznańskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk,page 163, 1993

- von Haxthausen, August (1839). Die ländliche verfassung in den einzelnen provinzen der Preussischen Monarchie (in German). Königsberg: Gebrüder Borntraeger Verlagsbuchhandlung. p. 78.

- Na przełomie lat 1819-1920 postanowiono rozwiązać klasztor, który był twierdzą polskości. W 1821 r., dokonano sekularyzacji, zmuszając zakonników do opuszczenia klasztoru. Wraz ze śmiercią ostatniego gwardiana, o. Tyburcjusza Bojarzynowskiego (1830), ostatni zakonnicy opuścili klasztor, który tego samego roku całkowicie opustoszał Archived April 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Wojciech Zenderowski, „Wiadomości Barczewskie”, 1999, 86, s. 11

- "sztetl.org". sztetl.org. Retrieved 2013-10-10.

- Dzieje Warmii i Mazur w zarysie, Tomy 1-2, Jerzy Sikorski, Stanisław Szostakowski, Ośrodek Badań Naukowych im. Wojciecha Kętrzyńskiego w Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe,page 300, 1981.

- Przebudzenie narodowe Warmii, 1886-1893 Andrzej Wakar, Wydawnictwo Pojezierze, page 23, 19821

- Słownik pracowników książki polskiej, Tom 1, Irena Treichel Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, page 97, 1972

- Charakterystyka zasobów i analiza stanu dziedzictwa kulturowego i krajobrazu kulturowego Gminy Barczewo (in Polish). Dziennik Urzedowy Województwa Warminsko-Mazurskiego. p. 31.

- Słownik biograficzny katolicyzmu społecznego w Polsce: Tom 2 Ryszard Bender, Ośrodek Dokumentacji i Studiów Społecznych, page 187 1994

- Teoretyczne, badawcze i dydaktyczne założenia dialektologii Sławomir Gala, Łódzkie Towarzystwo Naukowe, page 332 - 1998

- "Seweryn Pieniężny". www.ipsb.nina.gov.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2019-03-01.

- von Haxthausen, August (1839). Die ländliche verfassung in den einzelnen provinzen der Preussischen Monarchie (in German). Königsberg: Gebrüder Borntraeger Verlagsbuchhandlung. p. 78.

- verwaltungsgeschichte (in German)

- "THE FELIKS NOWOWIEJSKI MUSEUM". Culture.pl. Retrieved 2019-02-27.