Banlieue

In France, a banlieue (UK: /bɒnˈljuː/;[1] French: [bɑ̃ljø] (![]()

History

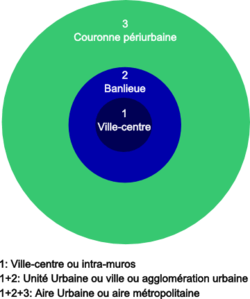

In France, since the establishment of the Third Republic at the beginning of the 1870s, communities beyond the city centre essentially stopped spreading their own boundaries, as a result of the extension of the larger Paris urban agglomeration. The city – which in France corresponds to the concept of the "urban unit" – does not necessarily have a correspondence with a single administrative location, and instead includes other communities that link themselves to the city centre and form the banlieues.

Since annexing the banlieues of major French cities during the Second Empire period (Lyon in 1852, Lille in 1858, Paris in 1860, Bordeaux in 1865), the French communities have in effect extended their boundaries very little beyond their delimitations, and have not followed the development of the urban unit existing prior to 1870 as well as almost all large and mid-sized cities in France having a banlieue develop a couronne pėriurbaine (in English: near-urban ring).

Communities in the countryside beyond the near-urban ring are regarded as being outside the city's strongest social and economic sphere of influence, and are termed communes périurbaines. In either case, they are divided into numerous autonomous administrative entities.

Banlieues 89, a design-led urban policy backed by the French government, renovated over 140 low-cost estates, such as Les Minguettes and the Mas du Taureau block in Vaulx-en-Velin. Improvements were made in road and rail access, cafes and shops were built, and the towers and blocks were made to look more attractive. In Vaulx-en-Velin, for instance, shops and a library were built, houses were built to make the landscape more interesting, 2,500 homes were renovated, and the blocks were repainted.[4]

Geography of the banlieues

The word banlieue is, in formal use, a socially neutral term, designating the urbanized zone located around the city centre, comprising both sparsely and heavily populated areas. Therefore, in the Parisian metropolitan area, for example, the wealthy suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine may be referred to as a banlieue as might the poor suburb of La Courneuve. To distinguish them, Parisians refer to a banlieue aisée (in English: comfortable suburb) for Neuilly, and to a banlieue défavorisée (in English: disadvantaged suburb) for Clichy-sous-Bois.

Paris

The Paris region can be divided into several zones. In the northwest and the northeast, many areas are vestiges of former working-class and industrial zones, in the case of Seine-Saint-Denis and Val-d'Oise. In the west, the population is generally upper class, and the centre of business and finance, La Défense, is also located there.

The southeast banlieues are less homogenous. Close to Paris, there are many communities that are considered "sensitive" or unsafe (Bagneux, Malakoff, Massy, Les Ulis), divided by residential zones with a better reputation (Verrières-le-Buisson, Bourg-la-Reine, Antony, Fontenay-aux-Roses, Sceaux).

The farther away from the Paris city centre, the more the banlieues of the south of Paris can be divided into two zones. On one side, there are the banks of the Seine, where working-class residents used to live (there are still pockets of disadvantaged areas) but also other areas that are especially well off. Also are large cities close to Paris, such as Chanteloup-les-Vignes, Sartrouville, Les Mureaux, Mantes-la-Jolie, Poissy, Achères, Limay, Trappes, Aubergenville, Évry-Courcouronnes, Grigny, Corbeil-Essonnes, Saint-Michel-sur-Orge, Brétigny-sur-Orge, Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois and Fleury-Mérogis.

Small communities that are socially disparate can be found in the Yvelines department with Villennes-sur-Seine, Chatou, Croissy-sur-Seine, Le Pecq, Maisons-Laffitte but also in the Essonne and Seine-et-Marne departments: Etiolles, Draveil, Soisy-sur-Seine, Saint-Pierre-du-Perray or Seine-Port.

Paris: Banlieues rouges

The banlieues rouges ("red banlieues") are the outskirt districts of Paris where, traditionally, the French Communist Party held mayorships and other elected positions. Examples of these include Ivry-sur-Seine, and Malakoff. Such communities often named streets after Soviet personalities, such as rue Youri Gagarine.

Lyon and Marseille

The banlieues of large cities like Lyon and Marseille, especially those around Paris (with a metropolitan area population of 12,223,100 inhabitants), are severely criticized and forgotten by the country's territorial spatial planning administration. Ever since the French Commune government of 1871, they were and still are often ostracised and considered by other residents as places that are "lawless" or "outside the Republic", as opposed to "deep France", or "authentic France" associated with the provinces.[5] However, it is in the banlieues that the young working households are found that raise children and pay taxes but lack in public services, in transportation, education, sports, as well as employment opportunities.[6]

Crime and protests

Since the 1980s, petty crime has increased in France, much of it blamed on juvenile delinquency fostered within the banlieues. As a result, the banlieues are perceived to have become unsafe places to live, and youths from the banlieues are perceived to be one important source of increased petty crimes and uncivil behavior. This criminality was seized upon to fan the flames of racism stoked by the Front National, a far-right political party led by Jean-Marie Le Pen, which rose to prominence during the early 1990s on a platform of tougher law enforcement and immigration control.

1981 riots

In the summer of 1981, events involving young Franco-Maghrebis brought about many different reactions from the French public.[7] Within the banlieues, events, called rodeos, would occur, where young "banlieusards" would steal cars and perform stunts and race them. Then, before the police could catch them, they would abandon the cars and set them on fire.[7]

In July and August 1981, around 250 cars were vandalized. Shortly afterward, grass- roots groups began to demonstrate in public in 1983 and 1984 to publicize the problems of the Beurs and immigrants in France. In doing so, the Maghrebis in France began to develop a stronger identity unified by the problems that have been imposed on them economically and politically. The banlieue became a unifying point for the marginalised immigrants of France even if there are various identities that constitute these individual groups. "We don't consider ourselves completely French... Our parents were Arabs.... We were born in France (and only visited Algeria a few times).... So what are we? French? Arab? In the eyes of the French we are Arabs... but when we visit Algeria some people call us immigrants and say we've rejected our culture. We've even had stones thrown at us."[7] Overall, the displacement of identities that Franco-Maghrebis feel becomes a unifying factor in French society and assimilation is particularly difficult because of their placement in the banlieue, and the violence portrayed at events such as the summer 1981.

2005 riots

Violent clashes between hundreds of youths and French police in the Paris banlieue of Clichy-sous-Bois began on 27 October 2005 and continued for more than 17 nights.[8] The 2005 Paris suburb riots were triggered by the deaths of two teenagers (of black and Maghrebi descent) allegedly/attempting to hide from police in an electrical substation and were electrocuted.[9]

2020 riots

From 18 April, Paris saw several nights of violent clashes over police treatment of ethnic minorities in Banlieue during the coronavirus lockdown.[10][11][12]

Filmography

- L'amour existe, Maurice Pialat, 1961

- 2 ou 3 choses que je sais d'elle, Jean-Luc Godard, 1967

- Elle court, elle court la banlieue, Gérard Pirès, 1973

- La Haine, Mathieu Kassovitz, 1995

- 100% Arabica, Mahmoud Zemmouri, 1997

- Ma 6-T va crack-er, Jean-François Richet, 1997

- L'Esquive, Abdellatif Kechiche, 2004

- Banlieue 13, Pierre Morel, 2004

- Neuilly sa mère, film by Gabriel Julien-Laferrière, 2008

- De l'autre côté du périph', Bertrand Tavernier, 2012

- Bande de filles, Céline Sciamma, 2014

- Divines, Houda Benyamina, 2016

- Les Misérables, Ladj Ly, 2019

See also

References

- {{Cite Oxford Dictionaries|banlieue|accessdate=25 July 2019}}

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Lepoutre, David. Coeur de banlieue: codes, rites, et langages. Odile Jacob, 1997.

- Modern Industrial World: France by Mick Dunford, Wayland Publishers Ltd, 1994

- Anne-Marie Thiesse (1997) Ils apprenaient la France, l'exaltation des régions dans le discours patriotique, MSH.

- La ville mal aimée, colloque de Cerisy-la-Salle, juin 2007.

- Gross, Joan; McMurray, David; Swedenburg, Ted (1994). "Arab Noise and Ramadan Nights: Rai, Rap, and Franco-Maghrebi Identities". Diaspora. 3 (1): 3–39. Reprinted in Gross, Joan; McMurray, David; Swedenburg, Ted (2002). "Arab Noise and Ramadan Nights: Rai, Rap, and Franco-Maghrebi Identities". In Inda, Jonathan Xavier; Rosaldo, Renato (eds.). The Anthropology of Globalization: A Reader. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 198–230. ISBN 978-0-631-22233-0.

- BBC News Timeline: French Riots, 14 November 2005 – retrieved 14 March 2010 http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4413964.stm

- Emilio Quadrelli, Grassroots Political Militants: Banlieusards and Politics, Mute Magazine, May 2007 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Police clash with residents in Paris suburbs amid lockdown". France 24. 20 April 2020.

- "Violence flares in tense Paris suburbs as heavy-handed lockdown stirs 'explosive cocktail'". France 24. 21 April 2020.

- "Unrest, hunger and hardship in France's locked-down suburbs". Euronews. 23 April 2020.

Further reading

- Bronner, Luc (2010): La loi du ghetto : Enquête sur les banlieues françaises, Calmann-Lévy, Paris, ISBN 978-2702140833

- Dikec, Mustafa (2007): Badlands of the Republic: Space, Politics and Urban Policy. ISBN 978-1-4051-5630-1

- Glasze, Georg; Robert Pütz, Mélina Germes et al. (2012): The Same but not the Same: the Discursive Constitution of Large Housing Estates in Germany, France and Poland. Urban Geography (33) 8: 1192–1211 doi:10.2747/0272-3638.33.8.1192

External links

| Look up banlieue in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- The New French Ghettos by Hervé Marchal & Jean-Marc Stébé, in Metropolitics.eu, 16 December 2010.

- The Barbarians at the Gates of Paris by Theodore Dalrymple in City Journal, Autumn 2002.

- The Other France – Are the suburbs of Paris incubators of terrorism? by George Packer in The New Yorker, 31 August 2015.

- So long, Marianne on burning girls and burning cars in France by Alice Schwarzer at signandsight.com

- The price of disdain French author François Bon has spent years giving writing workshops to youths in the suburbs that are now being set ablaze. He looks critically at where the violence originated and with despair at where it is headed, at signandsight.com

- French Riots Special A dossier with four related feature articles as well as a comprehensive collection of international voices from In Today's Feuilletons and the Magazine Roundup of sighandsight.com

- From Paris to Cairo: Resistance of the Unacculturated

- Website featuring underground rap music from the banlieues.

- Troubled Suburbs Erupt Again

- (in French) Audio book (mp3) of the introduction and first chapter of Éric Maurin's book : Le ghetto français, enquête sur le séparatisme social